Antoine Bruy – The White Man’s Hole

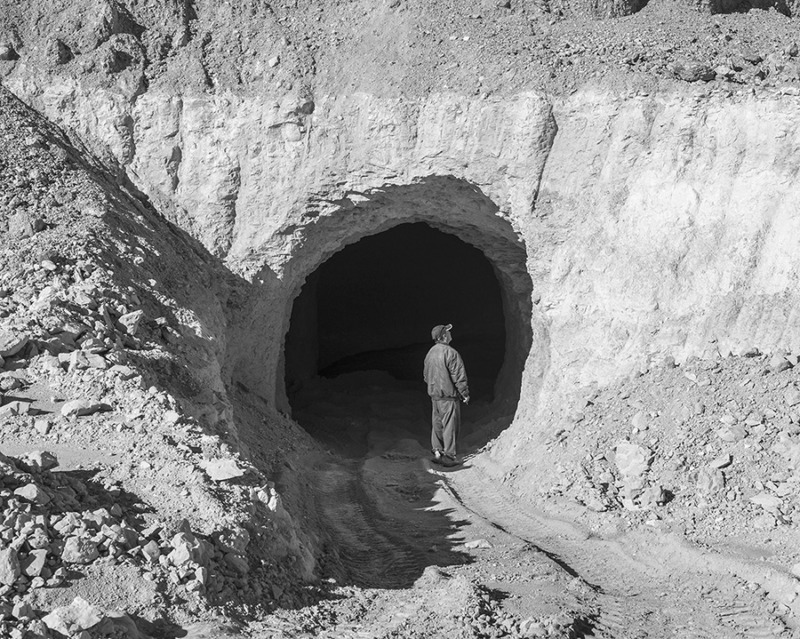

The most beautiful – and valuable – things often come at the cost of some tremendous effort, if not outright destruction; perhaps value of such things is in proportion to the difficulty of attaining them. Correspondingly, gemstones and precious metals have long had a role in human society, as symbols, of course, but also for the great wealth that their discovery promises. The pursuit of this wealth has reshaped not only individual lives, but national destinies as well. It also, quite incidentally, produces unique landscapes, along with unique social conditions for those who spend their lives in search of what is, literally, buried treasure. Antoine Bruy’s project The White Man’s Hole considers, in the first instance, the remarkably blasted and stark surrounds of Coober Pedy, a town indelibly shaped by the discovery of gem-quality opal deposits there in 1915. The quest to extract it in the decades that followed has produced a kind of lunar terrain and an ever-more hard-scrabble existence for the people who go in pursuit of it, not least because of the already inhospitable nature of the region. This project is part of a larger, on-going cycle of works looking at life in these ‘marginal’ areas of Australia, something of a common theme in Bruy’s work as a whole.

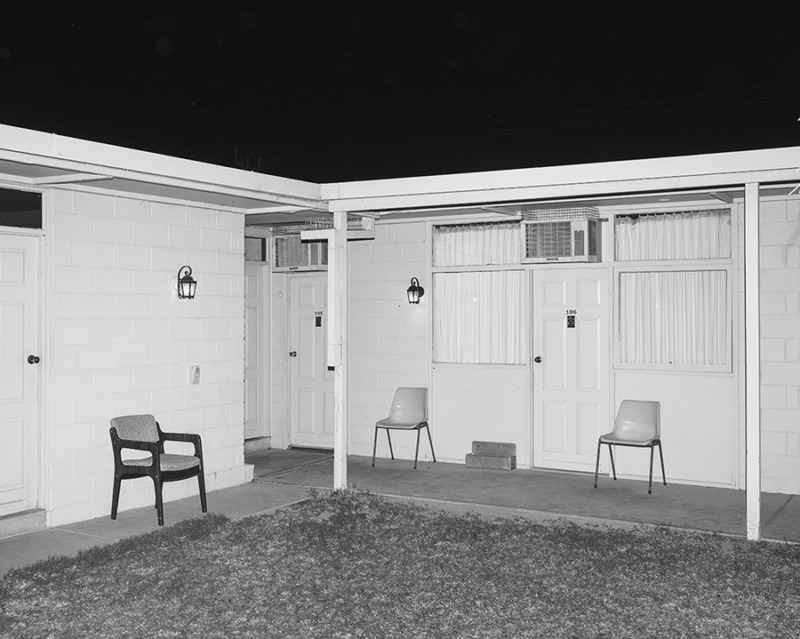

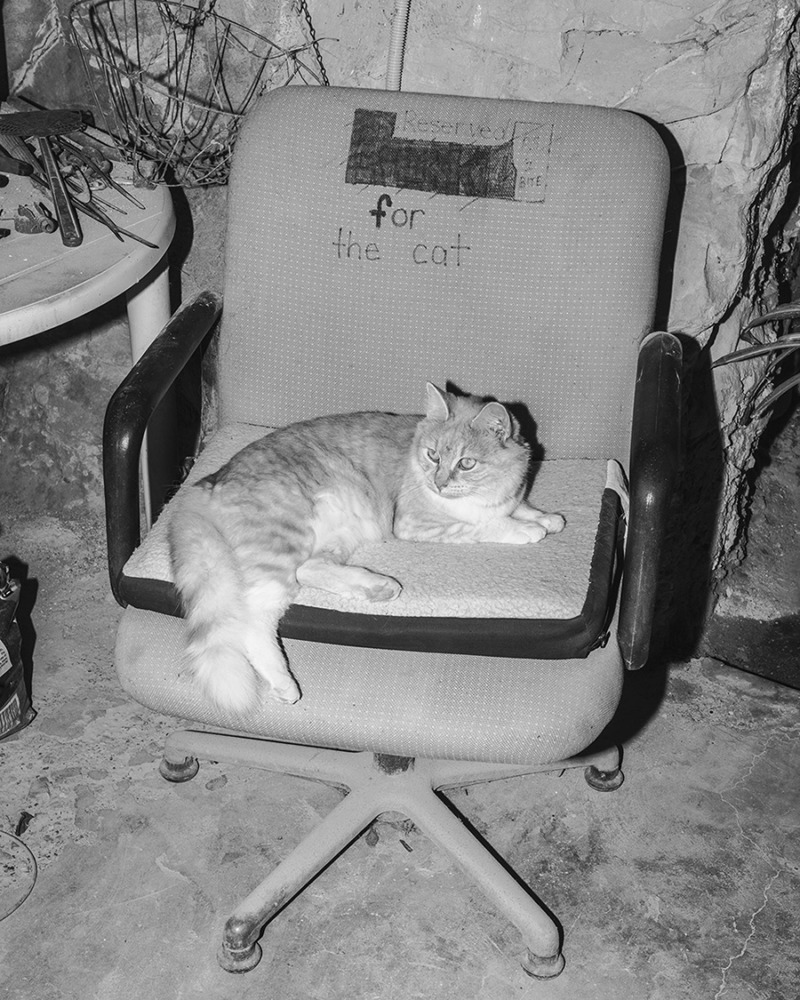

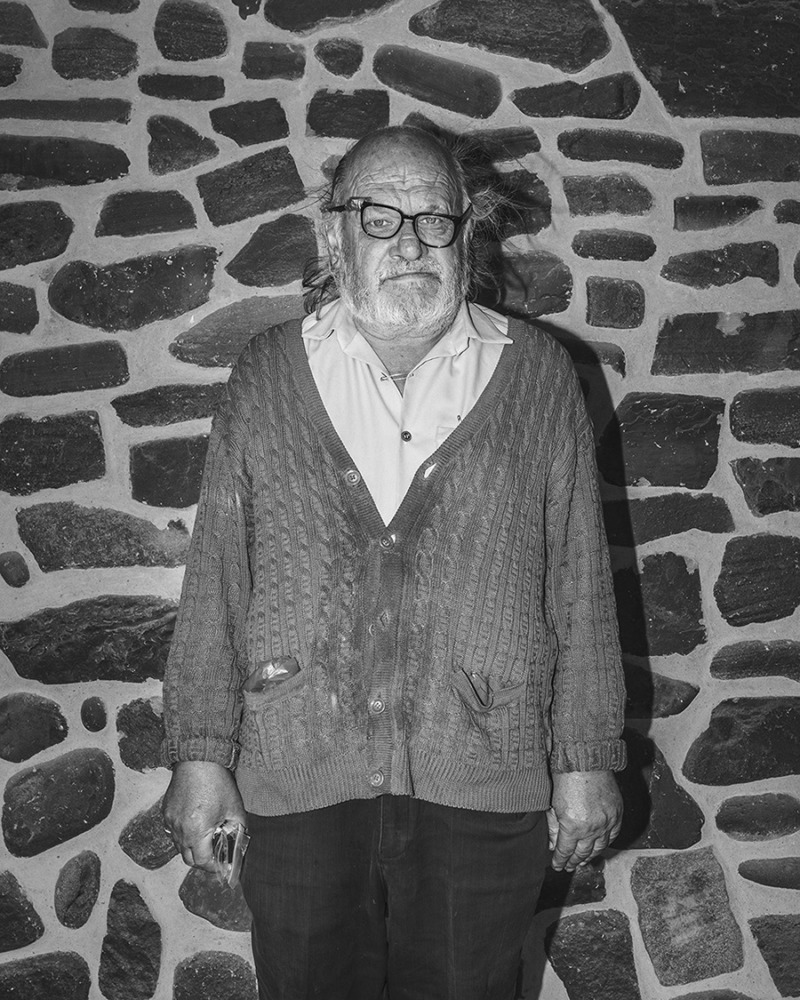

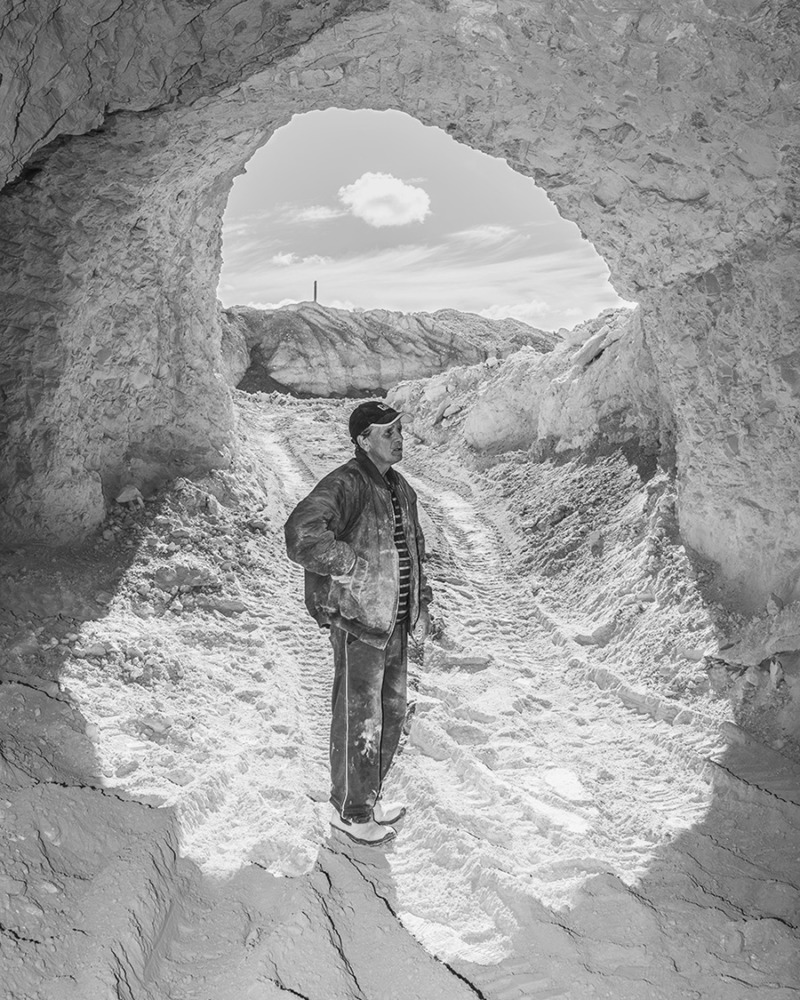

The images in this series has a very distinctive style, using a kind of flat monochrome, sometimes with a flash even in daylight; everything seen in this way has a flattened look, distances become abstracted, scale unreliable. In fact, it is difficult to see how the harsh conditions of the area might be represented otherwise. Even apart from the continuing human intervention in the landscape, the place is alien. Colour would feel unnatural here; it is a world that actually seems to exist in monochrome, scorched, coated in dust. Bruy’s pictures merely reflect this state of desolation, giving us a very immediate, tactile sense of the place that amplifies, rather than creates, the strangeness of an already strange place, whose geography and history appear like a kind of parable about human folly. But it is also a real place as well, with a history that is incarnated in the day-to-day events that Bruy observes, so the tension between this fantastical aspect of the landscape and the human reality is especially significant, even if the place is also, in many respects, man-made. Whatever the sociological (and indeed, metaphorical) import of his interest in the area, then, Bruy never loses sight of the fact that people do actually live here.

Bruy’s pictures evoke the characteristic dilemmas of a society premised on consumption – and on waste, dilemmas shown in a sort of concentrated, symbolic form, literally moving mountains to obtain tiny amounts of a material that we have arbitrarily declared to be precious, but that has no objective worth.

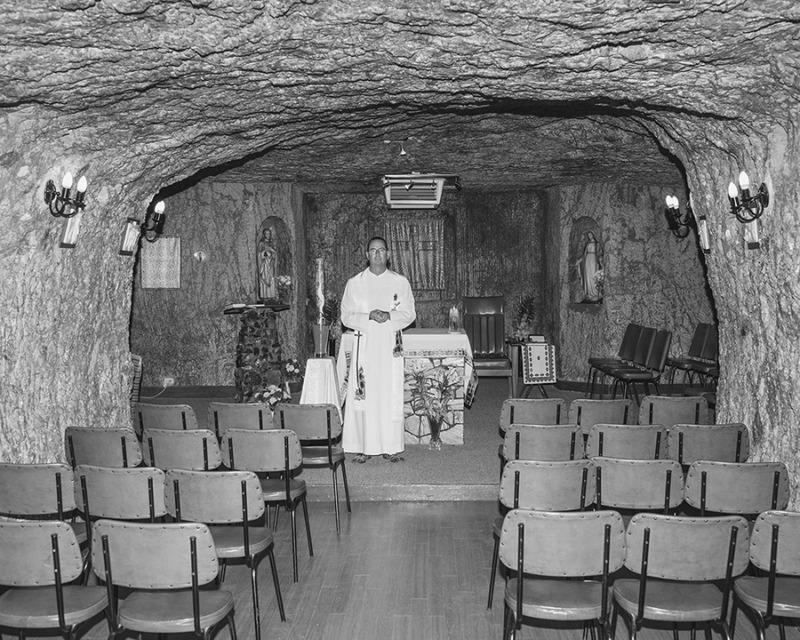

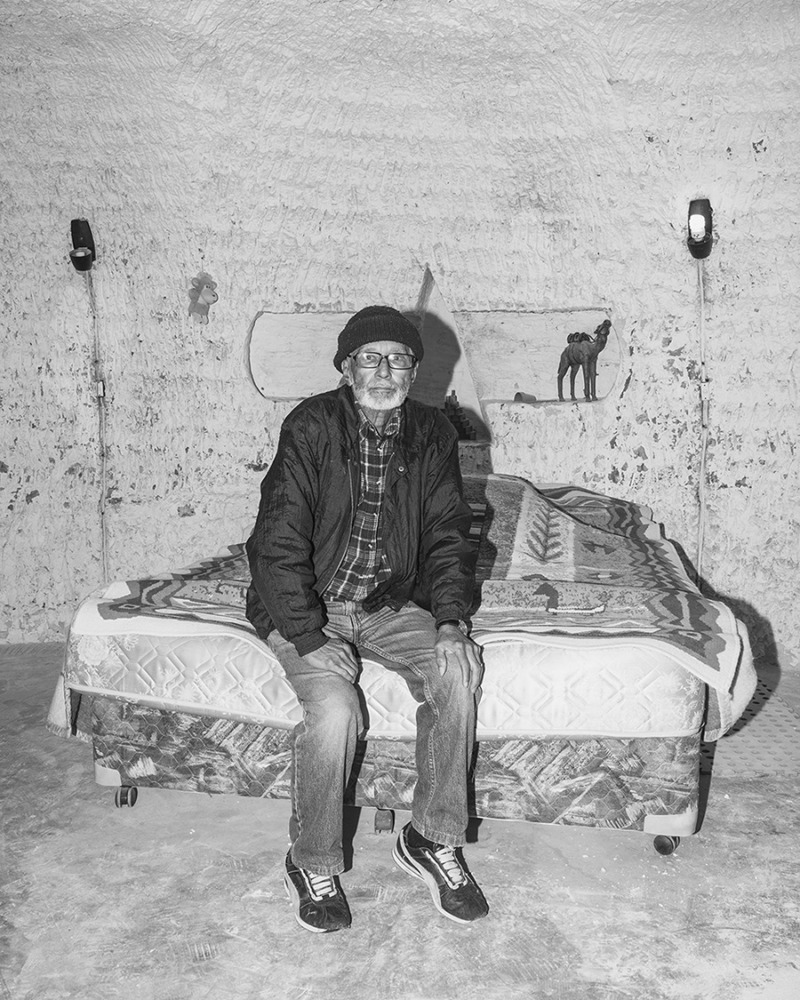

In fact, it is their living that makes for one of the most striking aspects of the work. Given the often unbearable heat, residents of the area have taken to dwelling in underground complexes called dugouts, that are essentially artificial caves and much cooler than a conventional house. It is somewhat incredible to see the ways in which all the comforts of home have been mapped onto these primitive abodes, with a real and even touching sincerity, despite the weird locale. This manner of living – and of worshiping, if at least one underground church is anything to go by – also suggests a curious, if hardly surprising, resemblance between these subterranean homes and the mines themselves, as if the town’s inhabitants had become accustomed to living under the surface by virtue of their work. Of course, the actual reason is, as we have seen, rather more prosaic than this, but the impression is one that persists nonetheless. There is even something insect-like about how the human tendency to colonise and consume a landscape is depicted, a resonance that Bruy perhaps doesn’t intentionally foreground, but that still seems a reasonable inference to draw. Indeed, consumption is another key theme in the work, the relentless urge to exhaust all possible resources, leaving destruction in its wake.

It is perhaps inevitable that the town and the area around it should look like a futuristic disaster zone, except of course that this future is now and, arguably, the worst has already happened. Certainly, nothing in Bruy’s pictures suggest boom-time expansion. If anything, we’re confronting the aftermath, and, looking to the other possible significance of those underground homes, the few survivors. It isn’t for nothing that the area has attracted the attention of film-makers in search of a plausibly dystopian backdrop. Equally plausible, though, is the way in which Bruy’s pictures evoke the characteristic dilemmas of a society premised on consumption – and on waste, dilemmas shown in a sort of concentrated, symbolic form, literally moving mountains to obtain tiny amounts of a material that we have arbitrarily declared to be precious, but that has no objective worth. The forces coming together here, the implacable logic of supply and the demand, produce a situation that presages the fate of all consumer societies, driving themselves out of existence on the basis of the very energies that formed them in the first place. In Bruy’s vision of it, then, this landscape is the reverse of consumption’s glittering spectacle, a grey near-wasteland, hollowed out by the demand for luxury.

Whatever the sociological (and indeed, metaphorical) import of his interest in the area, then, Bruy never loses sight of the fact that people do actually live here

In that sense, opal mining and the strange conditions it has produced – to say nothing of the novel living arrangements – serves as the pretext to address a more pervasive phenomenon. This isn’t to suggest, of course, that he neglects the particularities of Coober Pedy’s own history and the continuing difficulties of its present; it’s just that he is equally alert to the ways in which this place fits a familiar pattern, indeed is emblematic of it. We don’t really want to feel obligated to consider how the things we use and value, from gemstones, to oil, to the minerals employed in the manufacture of electronic devices, are the product of an inherently destructive system based on exploitation and ecological ruin. But here we see the consequences of this system, visible both in terms of its effect on the landscape and also, when the restless energies of the market have been redirected elsewhere – or the resource nears exhaustion – the social blight that follows in its wake, exacerbated in this case by Australia’s fraught colonial history. Bruy has recognised the extent to which these ‘systems’ are resistant to direct representation, so he has repeatedly chosen to concentrate on the points where they have become visible precisely because their integrity could not – and need not – be maintained.