In This Land: an interview with Zed Nelson

Zed Nelson has courted controversial topics before, with Love Me (Contrasto, 2009), a book examining the western ideal of beauty, and Gun Nation (Westzone Publishing Ltd, 2000) an in-depth study on America’s obsession with firearms. Nelson’s more recent book, In This Land however tackles one of the most difficult subjects of all, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In his own words Zed Nelson describes ‘In This Land’ as ‘a photographic series born from the challenges of attempting to understand the mindset of contemporary Israel. The project investigates the psyche of a nation trapped in a conflict deeply rooted in a struggle for occupation and possession of land.’ It is an examination of a people whose normality to us seems like an absurdity, a nation Nelson describes as ‘gripped by a collective siege mentality’.

The book itself is a measured look at the region and you are conscious of the slow process with the large-format camera that has gone into making it. The images are beautiful a transfixing picture of the landscape – however the tension of the situation people live in cannot be masked. The world in which the Israelis and Palestinians live is drawn into the frame whether it is highlighted overtly by the domineering wall that attempts to separate the people, or more subtly with military helicopters flying above a group of bathers at a seaside spa.

What was your impetus for going to Israel and the West Bank to make this book?

From a distance, the Israel–Palestinian conflict seems depressing and also hard to comprehend. And yet it remains constant, one of the most bitter, intractable disputes in the world. Israel was always a place that hovered in the background of my thoughts. The drip feed of depressing news reports from the region is ever present. I wanted to understand the mindset of contemporary Israel – to investigate the psyche of a nation trapped a seemingly endless conflict.

Israel is a tiny nation, surrounded by enemies both imagined and real. On my first trip, I travelled around the complete land and sea border of the country, exploring the notion that Israel is a nation gripped by a collective siege mentality.

When and how long were you in Israel to make the book?

I visited three times, twice on my own initiative and once on assignment for a magazine.

Is there an intention to support or disrupt popular opinion on the region, or is your aim simply to inform in an objective manner?

I am not interested in trying to be objective. I like having a voice – using photography to stimulate thought, debate and emotion – to tell stories about life and to point towards what I think is important. The notion of being a ‘documentary’ photographer is increasingly problematic to me. The implicit suggestion is that to document is to provide a reliable, truthful account of a situation. This is unrealistic. Perhaps we can only ever show our own version of a ‘truth’ as we perceive it.

As early as my first book, Gun Nation, I had already become aware of the limitations of a strictly traditional documentary approach. In Israel, I hoped to make work what would feed into a debate, even contribute in some way to a ‘solution’. I quickly realised how wildly optimistic and egotistical that notion was.

What were your feelings when you first arrived in Israel? Was there a dramatic shift during your time there?

I first arrived in Israel with a reservoir of sympathy for the Jews of Israel. The history of persecution, the horrors that took place in Hitler’s concentration camps and the resulting psychological scars, fears and dreams of a scattered people, all contributed to a basic, hazy, unfocussed feeling of support on my part for the notion of a Jewish homeland. But as I travelled into what is left of ‘Palestine’ – the occupied West Bank – I saw more clearly the plight of the Palestinians, and how the Israeli state treats them with a mixture of fear, contempt, and domination.

What I have tried to do is make connections; to show how past battles and disasters of past history have informed the contemporary Israeli mindset, creating a ‘siege mentality’. And also how the violence, seizure of land and continuing oppression inflicted on Palestinians has manifested itself in extreme acts of terror and violence in return.

With Gun Nation and Love Me you give us an anthropological look at Western society that we normally reserve for the ‘other’. With In This Land are you asking us to relate or once again look at the subject as peculiarities?

Over the last 10 years, my work has focused increasingly on the dark side of Western culture. I have looked at issues and tried to frame them in a considered, contextual way, questioning human behaviour and motivations. I am not looking at the subjects as peculiarities, in fact quite the opposite; I am asking that we see ourselves and our role in these extraordinary cultural situations.

Israel is a little different, as my starting point was that of an outsider, seeking to understand what is happening there and why. But the images attempt to show connections, to take the viewer on a journey that provokes a thoughtful response. But even as an outsider, you only have to scratch the surface to see Britain’s historical involvement in the history and politics of the region. So, ultimately the work is not about ‘the other’ – instead it asks that we consider our own personal position on the issue, both moral and political.

How did you find working in Israel? Was it easy to make your pictures there or were you under or overwhelmed by what your saw?

It is impossible not to feel overwhelmed by what you see in Israel and Palestine, or to remain untouched by the latent aggression, fear and anxiety that underpins everyday life there, for everyone.

The massive Israeli ‘security wall’ that today dominates the landscape is a spiteful scar on the place, and makes it impossible to forget, even for a minute, what is happening all around you. The 8-metre high, 465-mile long concrete barrier snakes around the Palestinian West Bank, swallowing up tracts of Palestinian agricultural land, slicing through communities and separating farmers from their fields and olive trees. Israel says the barrier is a security measure to deter suicide bombers entering Israel, but the international court of justice ruled the wall illegal under international law in 2004. Many believe it marks the Israeli-imposed boundaries of a future Palestinian ghetto-state. Even on the Palestinian side of the separation wall, Israeli settlements dominate the landscape. Half of the Palestinian West Bank has effectively been annexed by Israel, leaving the occupied population with disconnected lands and no viable existence. Only a strategy of permanent rule can explain this vast Israeli colonisation project and the enormous investment in housing and infrastructure on Palestinian land, estimated at $100 billion.

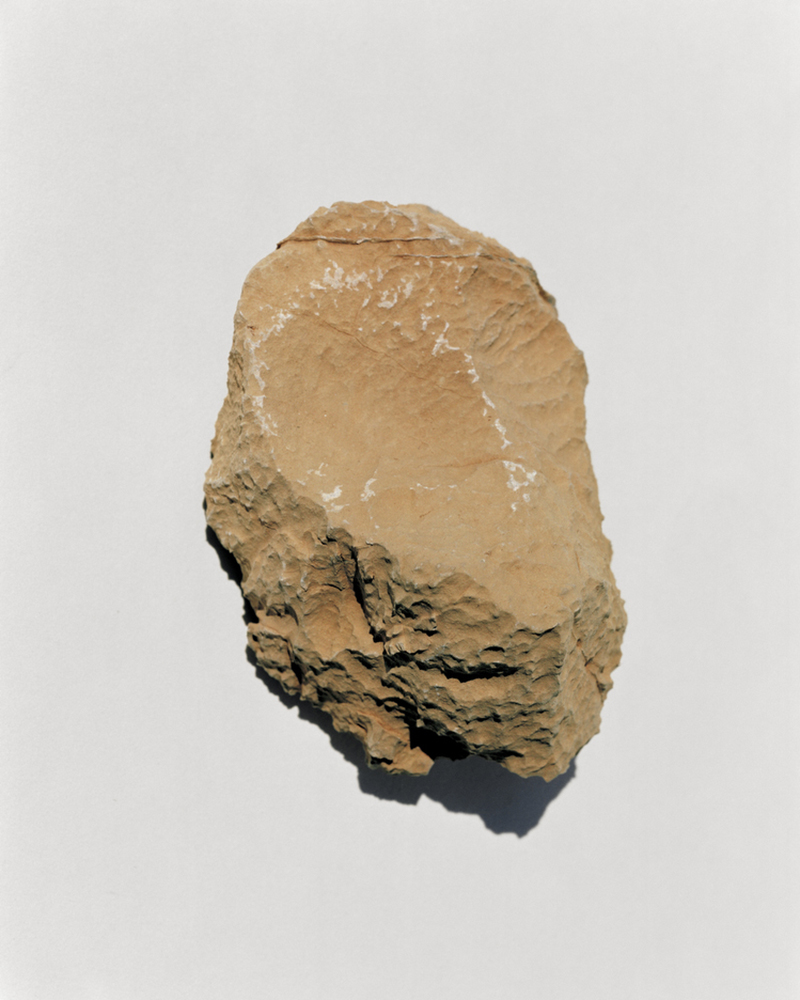

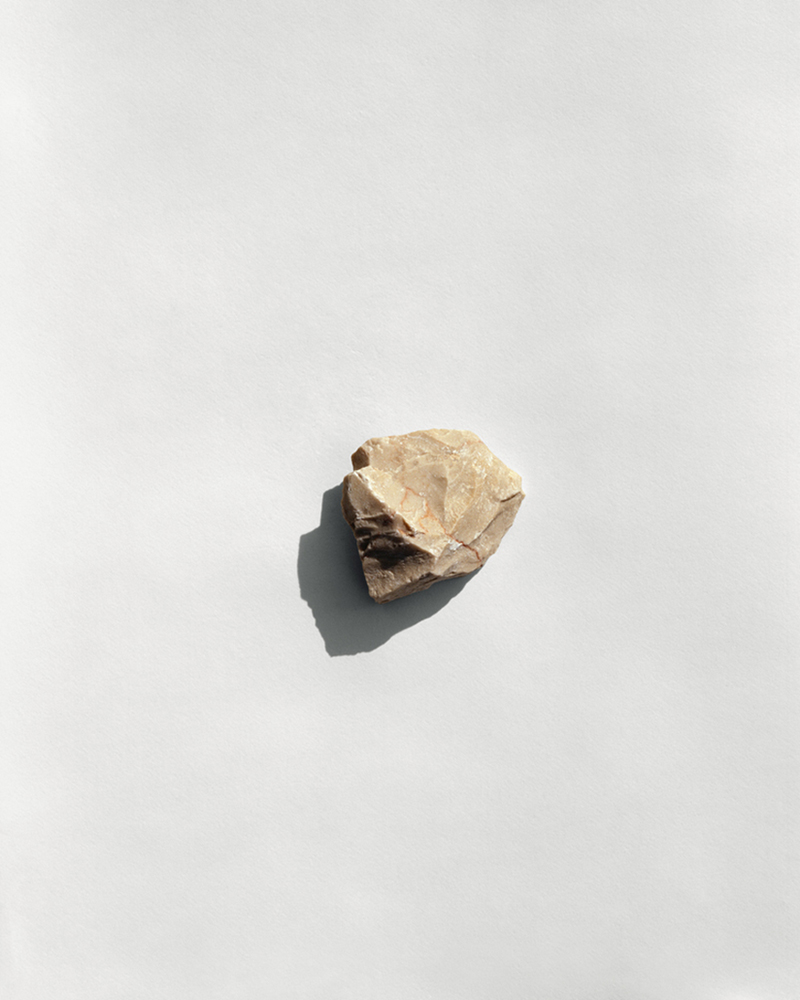

Your book also contains still-life images of rocks from certain regions. Picking them up, did you feel the significance of history in that object? Are you asking us to look at the importance of contextualisation when we look at these pictures with the accompanying text?

This series of still-life images, photographed with a large-format view camera in the intense light of Israel, depict stones gathered from places in the country invested with historical, social, religious or military importance. The ‘stones’ series was borne from a realisation that many of the images that come out of this place have become overly-familiar visual clichés – stone-throwing Palestinian youths in headscarves and militant gun-wielding Israeli settlers.

Using the more conceptual images of the ‘stones’ with accompanying text to underpin the project was a strategy to focus the mind differently, to provide background, and to make the point that this ‘conflict’ is utterly rooted in history, possession of the land, and the psychological reverberations of past events. So the ‘stones’ series was born and suddenly it allowed me to include insights into past history and also more recent events that informed what is happening in the country today.

There is a lightness and ridiculousness to some of the subjects of your other 2 books, do you feel you can do that with a book on Israel and Palestine?

There are light moments and ridiculousness to life, and particularly to human behaviour, that reveals itself sometimes in my work. But I did not feel much lightness in Israel; too many people are living in fear and deeply compromised situations. But of course there is some tragic absurdity. One image comes to mind of an Israeli man making tea with a gas mask on. (The Israeli population live in a permanent state of readiness for attack. By law, every Israeli citizen must have access to a bomb shelters and a gas mask).

How did you come away feeling after working in the region? Some of the other photographers I spoke to talked about needing a recovery period after the absurdity and harshness of the region.

It is emotionally draining. You come away feeling a great sadness for the people living there, both Palestinian and Israeli. It could be so different.

Do you have feelings towards the This Place project? It is funny that they have used a similar title and also done the triple translation.

It is a strange feeling when other work emerges on a subject you are involved in, particularly as that project involved some very well-considered high-calibre photographers, some of whom I really admire. But it is actually very interesting and great to have attention focussed on the subject. Normally it is a place that is ignored, unless there are extreme acts of violence or collapsing peace talks. The title is a bit similar, but these things happen. However the same use of the triple translation on the cover, the same as my 2013 book cover, was annoying.

When is the book coming out?

A limited-edition paperback book was printed to accompany the exhibition of In This Land that opened at the Noorderlicht Gallery in the Netherlands in February 2013. The main book was scheduled to follow after that. But there were printing problems and the project WAS delayed so I had to cancel the print run. Then I went off and got very distracted making a film. So the book project has only just come back on line. It will now be 2015.