Interview – Adjoa Armah of Saman Archive

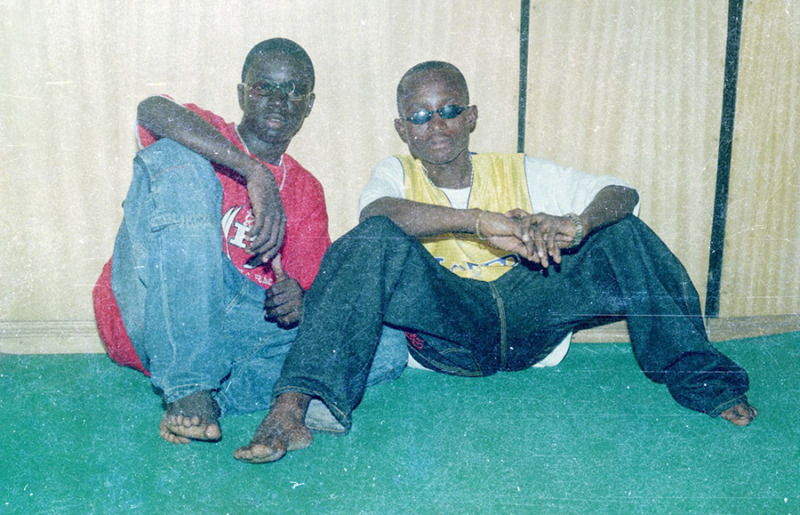

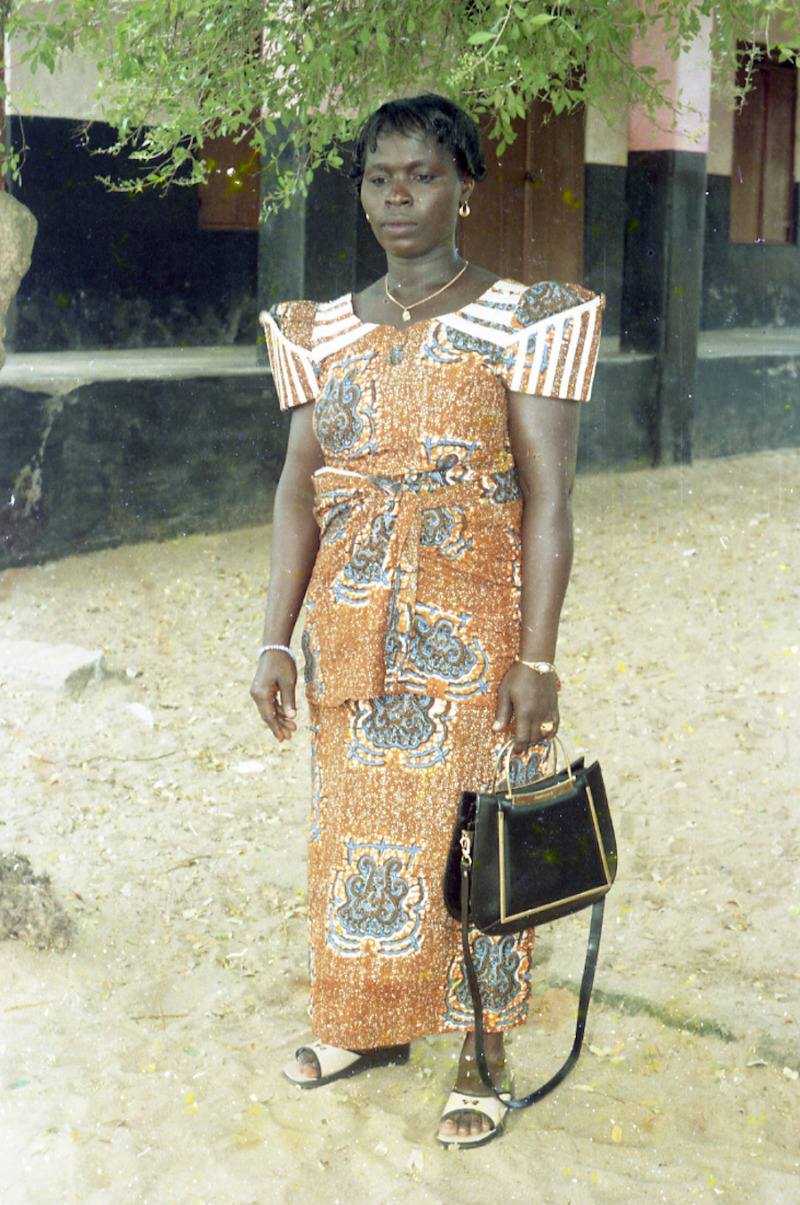

Sometime in the 1990’s in a city in Ghana, photographer Asante ‘Obra Photo’ Joseph, captured an image of two women in mid-conversation in almost identical poses. The women wear similar sunglasses donned in traditional clothing (both in hues of red) and clutch their purses in one hand and a club beer in another. This is decidedly a quirky and fun image. I spent a bit of time trying to decipher what they might be talking about, on what appears to be a sunny day. I also wondered if these women were asked to pose, or if this was a candid shot. This image makes me smile. As part of the Saman* Archive collection, this is just one of 30,000 photographic negatives that have been amassed by anthropologist and curator L. Adjoa Armah. Since 2015, Armah has been travelling across Ghana adding new additions to her collection, in the hopes of evoking the language of ancestry, belonging in space and what it means to be grounded in history.

The late cultural theorist Stuart Hall has said that the constitution of an archive represents a significant moment, a point of becoming something more considered, an object of reflection and debate. I think this is an apt way of describing the Saman archive, as with great care, Armah has been collecting stories and fleeting moments. The following is an excerpt from our conversation.

The archive currently dates from 1963 – 2010 and has 30,000 images. How did the archive come about?

The archive emerged by accident. I’ve got a fashion background so when I started going back to Ghana regularly, what I was interested in was researching textiles. I decided that I’d carry around an old 35mm camera when doing fieldwork because I thought it would make me look properly and force me to pay attention in a way that just carrying my phone around wouldn’t. I was shooting a lot at the time and ran out of film halfway through my first trip. A family friend took me to a part of Accra with a lot of photography shops to go find some film for my personal use. Although I struggled to find film, I did meet a lot of photographers who told me they’d destroyed their negatives. That was new to me at the time, but it is very common in a lot of West African photographic practices. I met one photographer who told me he had a few rolls he was yet to destroy and I asked him if he could give me those negatives. That’s how it started.

Can you describe your relationship to the photographers?

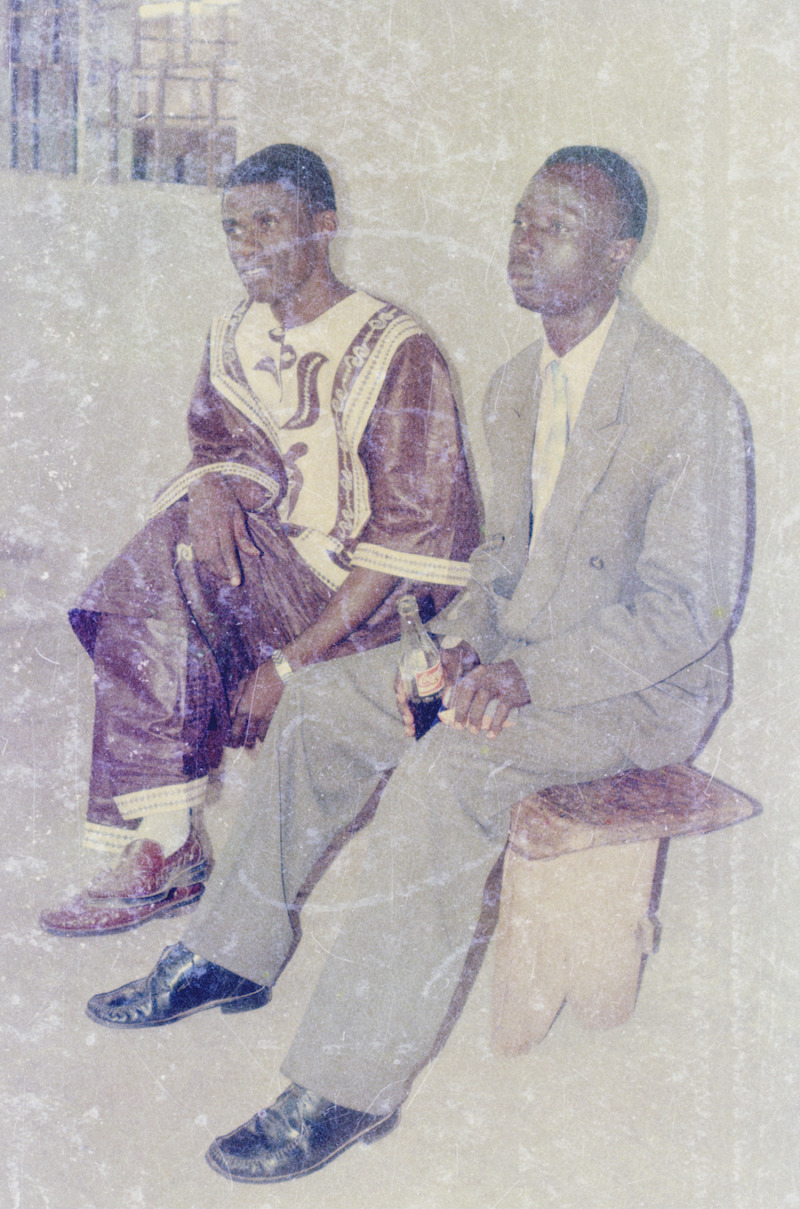

To begin with I would just hang out in printers in Accra and meet photographers there, get to know them and collect from them whatever was left of their negatives. After that initial trip, my textiles research basically fell by the wayside and I began returning to Ghana as photography collector. I’d just map out key routes and go on these cross-country trips in a trotro (shared minibus taxis), which are the main mode of transport in the country. Travelling in that way, and the serendipity in which I met many photographers, is all in the character of the archive. I can’t drive and though I could have found a driver who would have made collecting much more comfortable and efficient, being in a trotro and understanding how society functions through interactions had, stories told and conversations overheard while travelling, is all an important part of the personality of the archive. A lot of the formal photographic archives you find in Africa tend to tell the stories of elites, as such they are very much documentations of privilege. That’s not what Saman Archive is or what it could be. Choosing to travel in the way I do is an important part of staying mindful of what the point of this collection is.

The archive dates up until 2010, have you been in contact with any of the subjects? If so, how do they feel about being a part of a larger project?

I haven’t been in contact with any of the subjects in the archive and that is not something I am going out of my way to do. Though of course if an individual recognises themselves or a friend in the archive I would love to speak to them, however seeking them out isn’t the point of the research. I don’t want this to become an act of trying to trace individual histories. I think the more interesting conversation is that about communities and the nation, about taste and aspiration, the speed of travel of information in the pre-digital age. I feel like all of those are more interesting and useful conversations than trying to untangle the stories of individuals.

I am also really interested in the thread between the photographic conventions and visual codes you see in the images in the archive and the practices of young image makers of the diaspora who are responding to these traditions, whether its through what they’ve seen on Instagram or in family albums, personal memories or on the streets. The subjects that I am focused on are creative practitioners, first and foremost. That is not to say I don’t take my responsibilities toward the subjects in the photographs seriously; I absolutely do. Actually, that fact that I take my responsibility towards the subjects in the photographs seriously is part of the reason I have de-emphasised them in the research.

What is the role and responsibility of yourself as the curator/keeper of the archive and the broader public?

The reasons that a lot of these negatives have been destroyed are very good reasons around professional propriety and ethical responsibilities towards sitters. Essentially, whatever responsibilities the photographers had towards each of their sitters are now my responsibility. The purpose I serve is basically to mediate between the individual needs of photographers and sitters and the greater public value of creating conversations with, around and about these images that to some extent, should not exist for anyone but those sitters. If that’s the case, how do you use and show them responsibly? The images I have made available publicly are a tiny proportion of what is in the archive and although the images are being digitized, I’m never going to just put all of it on the internet. That is not appropriate and my job is finding the right balance between making the archive available for those who need it, initiating conversations that are useful and keeping private that which needs to be private.

These images feel familiar to me. They point to some of my own family albums and to a larger narrative around the photograph’s ability to be a keeper and disseminator of stories.

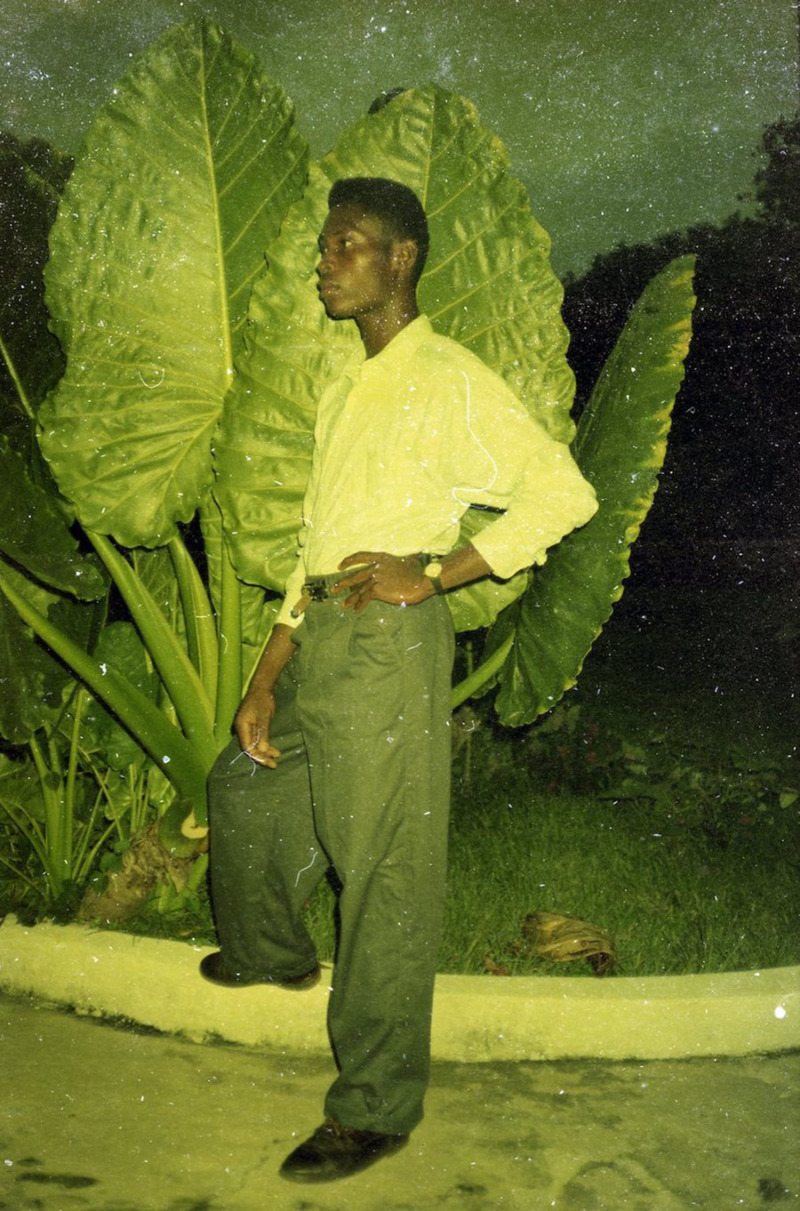

For me, the images are exciting because I do see people who look like my family in them, but beyond this, I am also very much interested in them as storytelling devices. Again, not so much about trying to trace the exact story of this exact person in an individual image, but looking at these visual documents and staying open to the stories that can be read, and using fiction to fill the gaps between the individual stories and the objective visual data present in the image.

Anthropology of/with the prototype is an area where a lot of interesting work has been done that has informed my thinking. A prototype functions as a tool that allows something to happen but is not actually a thing in itself. This is something I am interested in, especially since photographic negatives are prints that haven’t yet become prints so the negative is always the prototype for something. I like to think of this something not as a visual something but a narrative something. I am not very rigid in the historical accuracy of these stories but interested in the way fictions can be written into these photographs, interviews and stories.

What are your thoughts on the power of the Saman archive?

I am interested in the way it can act as a kind of anchor for the community. Although I generally consider community at many scales, right now I am talking about the broader community of the African diaspora. Although as you say, the images do not need to emulate your particular upbringing to feel familiar, I do think that when they do is a different level of engagement. At the moment, there are so many artists similar to me who are preoccupied with visual culture and style from ‘back home’ and feeding that back into their practice – whatever that may be. Maybe there’s always been a preoccupation amongst the children of immigrants about what home looked like and what that meant for their visual inheritance. Pre-internet, realistically pre-Instagram, this visual inheritance was basically limited to what you could see in family albums, whatever cable channels your family had access to and a pretty narrow range of imagery beyond that. Now its broader and much more multiple. What I want from this archive is for it to act as a space for artists of the diaspora, who beyond being connected by ancestry or land, as artists interested in these conversations form a community of a certain set of values or preoccupations. First and foremost, the archive is a resource for them. That is not to say that others cannot or should not get value from the material, and that is not to say all artists of the diaspora are or should be interested in these values. I just feel that it is important to state that this space is to serve those who are interested in this kind of material beyond trends or one-off projects but are responding to the material in a much more visceral way, grounded in identity before aesthetics.

Do you feel that the Saman Archive as it stands, captures a particular period of time in Ghana? Are there any geographical or physical signs that you can pinpoint?

Well strangely enough, when I first started collecting and didn’t know Ghana very well, these images felt very broadly in terms of being from West Africa, because my eye wasn’t well tuned to specific cultural signifiers. Now, the more I look, the more Ghanaian it feels and the more I can read certain regional signs. I can recognise buildings and geographic details, notice certain trends and make informed decisions about dating the images. I think the archive doesn’t capture a period of time because that is too narrow; however, it does capture multiplicity. Having access to the content of the archive and going through the process of conducting fieldwork and collecting material, has helped me understand how complicated this place I grew up thinking I knew, but quite clearly did not. It sounds naive and very silly to say a nation of 100’s of languages and ethnic groups is complicated. However, when you grow up in an immigrant home, you end up with an understanding of yours or your parents’ place of birth quite narrowly, through their stories and almost frozen in time because home for them is essentially that place as it was when they left. The archive is interesting because it’s not singular in what it represents.

There are certain periods that I am especially drawn to. It’s the fashion girl in me and there are certain batches of negatives that are personal favourites because everyone just looks so cool. My favourite period in the archive is the mid-90s across the lower Volta region; a lot of my favourite images come from there. That was a great period for shoes, bags, and frames, there are a few images from that period that I refer to in my personal style. There are certain images in particular that I’ve built Instagram alerts around.

Would you like to re-interpret the archive and its current role in society?

There are certain conversations that I am interested in having that the archive facilitates. I think it is this fascinating space that draws people in. As far as its current role in society, I don’t think it is necessary to have images from the archive all over the place. The collecting is enough. Its ability to be an anchor for community and be a resource for people who are interested in these stories to utilise. As much as there is value in making archives and images available, I am a very big believer that not everything needs to be made public. I think there is a cheapening of the material in some ways with that. Particularly in this archive where I have spoken to photographers about privacy and secrecy in photographic practice and the photographer’s ethical responsibility to their sitter. I think the archive can facilitate a type of storytelling and the bringing together of narratives and dialogue that can re-interrupt in the way we think about our collective visual inheritances, without putting 1000’s of images on the internet. That is not interesting or productive. As well as being an aid for story-telling, it is a great visual research tool for design and art making in general. I am interested in its generative potential, how it allows the archive to stay alive and dynamic while being respectful of the issue of privacy.

What role do intimacy and memory play in your practice?

When I talk about intimacy I am not talking about romantic intimacy or intimacy in an interpersonal sense. I think of it in a spatiotemporal sense, about diasporic intimacy and what it means to feel connected to a place or context. I think about the anxieties that surround this kind of intimacy. What it means for me as a Ghanaian-born Briton and the rights I have to develop these narratives. I am very aware that my ancestry or me having a Ghanaian passport doesn’t give me a right to speak in all instances about what a Ghanaian or African experience is. I think some people can be quite lazy in the way they act as though their ancestry means their right to represent a place is a given, it isn’t. I’m interested in the questions of what it means to feel close to a place on a visceral but know that there is a lot about it that is out of your grasp for whatever reason. In a way, it is kind of like trying to get to know a romantic partner. There’s something in that gap between thinking someone is yours but having them keep you at arm’s length that can be scaled up to the Diaspora experience of return.

As far as memory, though the archive spans almost 50 years, a lot of the material is from the late 80’s till 2010. Personally, a part of my connection with the material is that a lot of it fits within my own lifetime. Birth, through to moving to London as a child but before social media was Social Media. I feel like the contents of the archive are filling the recent history of this place that I missed out on getting to know while growing up in London.

What do you hope to accomplish with the Saman Archive?

That’s a tough question. In practical terms, as far as the question of access, I eventually need to end up physically in an archive in Ghana. At the moment, I am based in London, and so is all the material and the fact that you’d have to come to London to access this material is a huge issue for me. I have no interest in being part of that tradition of collectors, curators, anthropologist, whoever, whose activities basically interrupt access to objects in their contexts. In that sense, there is a certain repatriation that needs to happen. As far as what I want to accomplish with the archive, I want to function as both a springboard and an anchor. An anchor in that if you are interested in Ghanaian photographic traditions and self- representation and style, this is a place you can go and respond to. And a springboard for this community of value, people similarly to me questioning the position of questions of ancestry and memory and what it means to belong to a place and make connections there and encounter that place. I can’t be too prescriptive about that right. It’s about who else comes to it and what they bring.

* The word saman is an Akan word used to colloquially refer to the photographic negative, it can be translated as ghost in English.

Asante ‘Obra Photo’ Joseph. Accra. Circa 1990. Portrait of bride after wedding service.

Asante ‘Obra Photo’ Joseph. Accra. Circa 1990. 5 women photographed after church service.

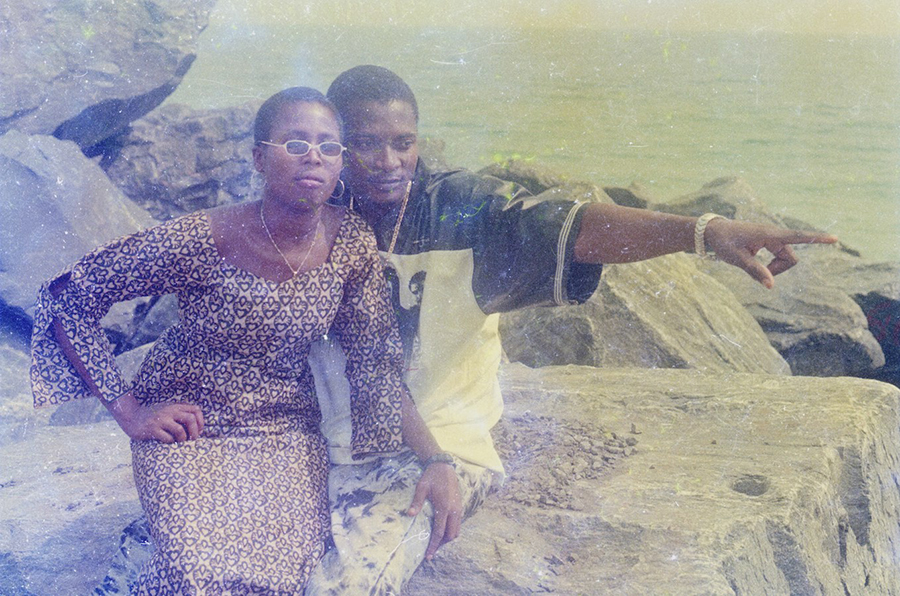

Perseverance Photo. Angola. 1990’s. Couple photographed at the beach.