Interview: Zachary Norman

When did you start to think of Exotic Matter as a cohesive project? How did this evolution come about?

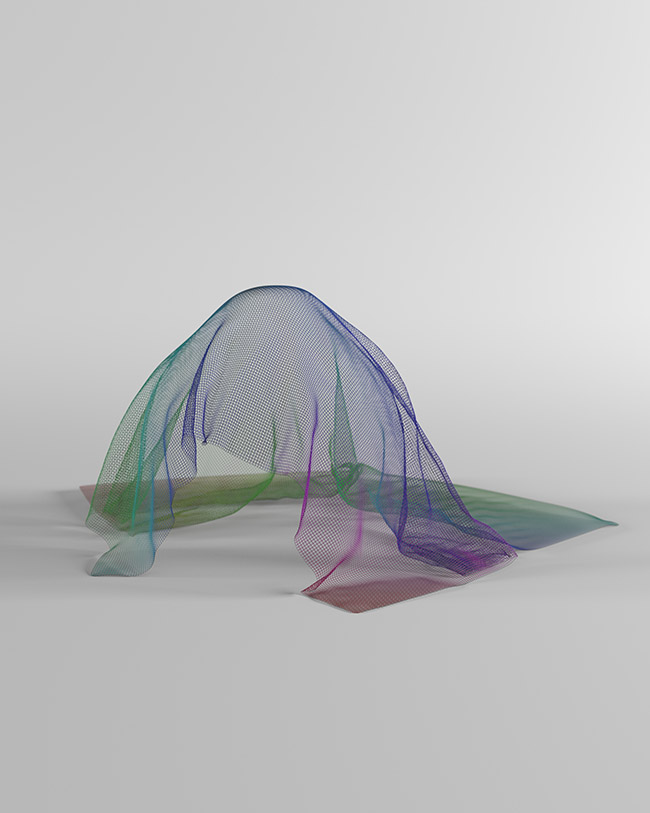

I started to think of Exotic Matter as Exotic Matter maybe one or two months ago. I was working towards my thesis show and producing as many images as I could every day and then kind of stepping away at the end of each of week and seeing what came out of that. I started to notice a trend in which images I was most drawn to – those in which I had generated some kind of material that seemed impossible or foreign. It was at this point that I began to think of the work as Exotic Matter and started to refine those types of images. By doing so, I had to leave behind countless other ideas that I am eager to revisit in the following months.

In your statement you say that your images ‘can be seen but not touched’; I read that as a form of failure in these photographs. The limit between what’s real and what’s not is extremely evanescent and sometimes confused. Photography and truthfulness have always been a traditional – if not easily contested – binomial in the history of the medium. In your work you reframe this dialogue in unexpected ways by generating images made through non-photographic techniques and digital software. I am interested in this discussion around the idea of truthfulness in photography. What does ‘truth’ mean for you? Do you think photography can be a truthful medium nowadays and how does truthfulness enter into your thinking about your work? Where is truth present in a digital experience?

I don’t think I maintain a definition of truth. I think the important thing for me is to acknowledge the complexity of the ways in which our senses, experiences and countless other factors inform our perceptions, thoughts and behaviours. I suppose the closest I might come to ‘truth’ would be an understanding or at least appreciation of its impossibility given the multiplicity and intricacy of these variables. Photography is just one of the ways in which we perceive the world. It is therefore subject to all the aforementioned variables and devoid of any kind of inherent truthfulness. The question for me is not whether or not photography can be a truthful medium nowadays but rather to what extent it may still be perceived as such and how this perception might affect people’s thoughts and behaviours.

I see the objects in your pictures working as digital ruins. In my mind the idea of ruin implies something material that physically decays, whereas your ruins are ephemeral by the definition of ‘digital’ as ever changing.

This is an interesting idea. I hadn’t really thought of these objects as ‘digital ruins’. I had actually been thinking of them as less ephemeral in many ways than physical objects, at least in a practical way, because I can lock them into place in the computer and return to them days, weeks, months or years later and they will still be there frozen in space. I suppose though that they are very ephemeral in a way, in that their existence is dependent on one’s perception of them. I’ve kind of been thinking of these digital objects like that refrigerator light from your childhood whose on-or-off-ness when you closed the refrigerator door was a great mystery.

How important is it to you that your images function as physical objects?

I tended to think it was not that important but after seeing the images printed large, mounted, framed, etc., I think it might be quite important or at least transformative in an interesting way to make the images into physical prints. Having said that, I recently attended a talk about James Clerk Maxwell’s famous tartan ribbon photograph, which is widely considered to be the first colour photograph. However, it was originally realised as an ephemeral projection on a wall and not a physical print. The talk dwelled on the distinction between these forms and paralleled this situation to that of the materiality of the digital photograph in the twenty-first century. These questions are very interesting to me but they’re more compelling as questions than as answers. In other words, I’m very interested in materiality but I suppose more so in the curiosity it invokes and possibilities it presents than any kind of concrete understanding of its relationship to photography.

Your pictures often give the sense that you are documenting materials you brought back from another planet. In this sense I think that the word ‘exotic’ fits particularly well to this project. Your approach is a scientific one, as if you are taking pictures of those experiments for the sake of documenting a specific chemical reaction or an unknown tissue or surface. Is this scientific method something you recognise in your practice?

I’ve always been interested in the description of science as dispassionate. It seems like a misnomer to me; I imagine science as a highly passionate endeavour. I think art is inversely parallel to science in this way – it’s ostensibly this emotional and intuitive practice but actually it’s also a very rigorous and methodical one. I approach most things scientifically I suppose, or at least obsessively and rigorously. I enjoy getting to the bottom of things. I’m not sure if I ever have (got to the bottom of a thing) or if it’s even possible but the process is an interesting one to me. All of the images in Exotic Matter are of imagined experiments or of the information extrapolated from one of those experiments. One of the most attractive things about making Exotic Matter was how much information I generated along the way. I decided not to treat any of that information as extraneous and instead tried to find ways to integrate it into the work.

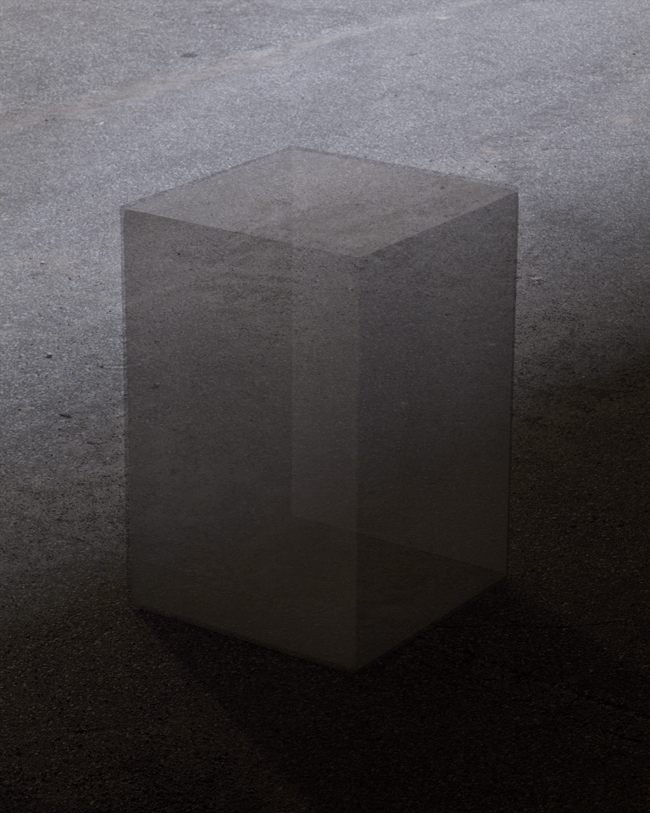

I also find it interesting that some of the images are constructed as if they are installation shoots of these objects. In looking at them, I find an interesting contrast between the pedestal and the object on top of it. Further, I have a familiar relationship with the gallery pedestal – it is an easily identified and conceptually loaded object, yet the object you place on top is made of unknown matter. Why did you choose to use this composition that looks so much like exhibition shots? And have you ever thought to show the pieces as sculptures instead of prints?

In the installation shots I hope there is something vaguely familiar and possibly even believable. I suppose I want people to ponder, at least, initially, where this object exists, how it is defying gravity, etc. I think these questions lead people in interesting directions.

I have considered showing these pieces as sculptures; I’m currently working on realising this. I’m not sure how the pieces will differ. My fear is that they will lose their highly desirable position in the liminal space between physical and virtual. My hope is that they will look really, really good…

Do you consider the online space as the final space to show your work?

No, I really enjoy exhibiting work in the gallery. I’m really interested in how my work might be disseminated and exist in different contexts on the internet but I think there is something equally interesting about making these images physical and presenting them in the fixed environment of a gallery. My thesis exhibition is currently on display at the Indiana University Art Museum. In the adjacent gallery there is an exhibition of Matisse paintings and some pre-Columbian sculpture. I think this juxtaposition is a really interesting one and one that may not have yet have been realised on the internet.

I see collaboration as a medium in itself. Lately I found myself thinking of it as one of the most productive ways to produce art. How did you meet Jason Lukas and Aaron Hegert and why have you all decided to start this conversation about the condition of photography? What are some of your thoughts on the condition of photography today?

I met Jason and Aaron at Indiana University. Aaron and me started the MFA program together and immediately recognised some shared interests. Meanwhile, Jason was in the BFA program. In the spring of 2013, Aaron and I had a show lined up at a gallery in Cincinnati for which we planned to collaboratively produce a body of work. Around this time, Jason was producing his thesis show. When Aaron and I saw Jason’s show we immediately recognized an immense amount of talent and mutual interest so we invited him to collaborate with us on the exhibition in Cincinnati. Somewhere along the way we decided to expand this one-time collaborative effort into a full-on collective. I think we all had a mutual and, initially, implicit interest in the condition of photography in the twenty-first century, one that we later made more explicit in our collaborative work.

On the condition of photography – it has become the norm for people to produce and consume images in great quantities. This normalisation of the technology, to some extent, precludes conscious investigation or reflection by its consumers. I think this is an interesting situation. I think photography’s role, in the context of art, has played out very differently than it has in mainstream culture. Instead of being normalised and taken for granted artists have begun to investigate and deconstruct its functions and meanings, perhaps in response to photography’s pervasiveness in mainstream culture. I think this response is responsible for the shift we’ve seen in photography from street, neo-documentary practices to more self-reflexive and interdisciplinary practices. I’m very happy to be a part of this shift.

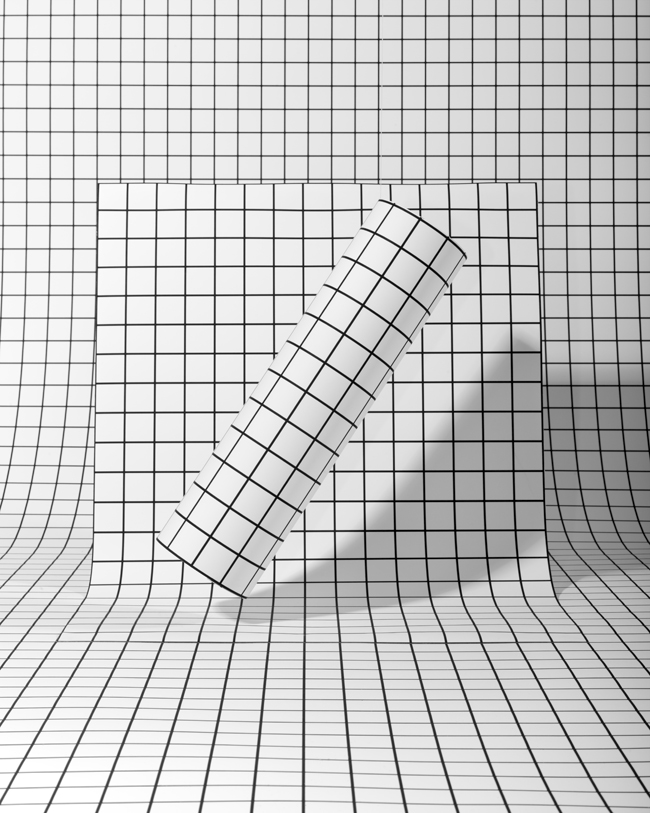

‘Each iteration contains some elements of the previous iterations, either formally or materially, while other elements have been replaced or left behind entirely.’ This layering process makes me think of some things I asked you about Exotic Matter – the way layering is discussed in this statement reminds me that ruins can be a space to experience the layering of time in a physical way. Can you talk a little bit about why a layered system is necessary in a collaborative process?

In Everything Is Anything Else one of our primary intents was to approximate the way in which networks work to generate and perpetuate ideas and trends that seem to come about through an almost Darwinian process. In Everything Is Anything Else we made images and shared them with each other anonymously, to some extent, via a closed network. We then made images in response to those images and shared those with each other and so on and so forth. All of these images and ideas mutated, expanded, contracted, disappeared and reappeared. Ultimately, the most compelling ideas survived and were exhibited in the gallery. However, the archive that informed the exhibited images is as important as the final images themselves. I suppose those images function in a way similar to that of a ruin, in that the progress of time, style, ideas, etc., is apparent in a contained space or set of forms

Looking at your education, I see Kyoto, Nairobi and Indiana. These are three different worlds. How has living in such places affected you and the way you work? Do you have one particular thing for each place that you think might have been crucial in developing your work?

Oddly enough, I hadn’t really considered this before now. I was quite young when I lived in Nairobi. I was still very interested in photography but a very different type of photography. I interned at a large newspaper in Nairobi where I was sent out into the field to cover everything from gang busts in the slums to speeches by dignitaries such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu. I think these experiences informed a lot of the work I made between undergrad and grad school – more straight, documentary-esque work.

I was at the Kyoto University of Art & Design last summer. While there, I worked on a collaborative project with students at the university. I think because the language barrier there was so severe we really had to work hard to make our ideas implicit in the images. That experience taught me a lot and has been immensely helpful in my current work.

As far as Indiana goes, I’ve met a lot of great people here with whom I’ve collaborated either directly or indirectly in some way. While I think many of us feel geographically isolated while attending school here the internet allows us to connect with artists from around the world. Living in Indiana has forced me to find alternative ways of collaborating and conversing with artists from all over. This has been a really useful exercise. I’ve also become a devout Pacers fan and look forward to seeing them beat the Wizards in the second round of the playoffs.

You just graduated: congratulations! How do you see your life after grad school? Any particular projects coming up?

Thanks! My life after graduate school is still very much undetermined. In terms of upcoming projects, Aaron, Jason and I (as the EIC) have been included in an exhibition, ‘Fragments of an Unknowable Whole’, at Ohio State University that opens in mid-May. The show includes Midwest-based artists who are exploring a particular shift in the subject of the photograph over the past decade. The exhibition includes artists such as John Opera, Jessica Labatte, Jordan Tate, B. Ingrid Olson and others. We’re really humbled to be in such great company. We’re making new work for the show that incorporates many of the ideas and processes we’ve developed independently of the collective in the past few months. I’m very excited about it.