Lewis Bush – War Primer 3

All spreads courtesy of the artist

WAR PRIMER 3 by Lewis Bush (self published, 2015), FREE DOWNLOAD

The last decade or so has seen a significant shift in documentary practice away from more traditional strategies, a move that has coincided, unsurprisingly, with the precipitous decline in familiar outlets for long-form photojournalism. Of course, photographers can still make ‘socially engaged’ projects in much the same way – and many do, with conspicuous success, but there is an equally strong contingent of artists willing to engage with the form and take it into uncharted territory, a willingness prompted by the sense that traditional strategies for dealing with these subjects are not always capable of accounting for the changed world we live in – and also signals a recognition of the cultural baggage that has so often undermined the engaged documentary tradition. Perhaps the more celebrated and energetic exponents of this tendency is the duo of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, who have produced a steady stream of projects scrutinising both the socio-economic conditions of contemporary life – and the means by which those conditions have been represented, especially through photography. These projects generally culminate in some form of publication, which has of course emerged as one of the dominant forms in the medium.

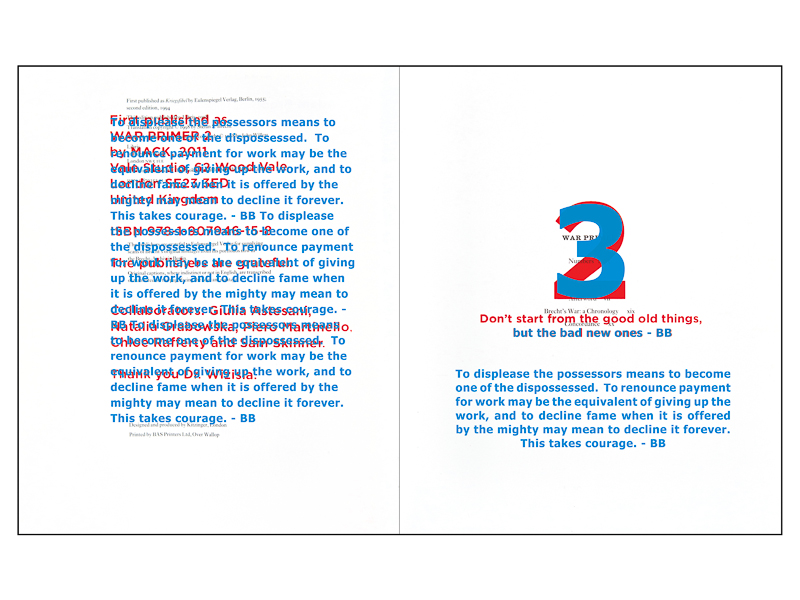

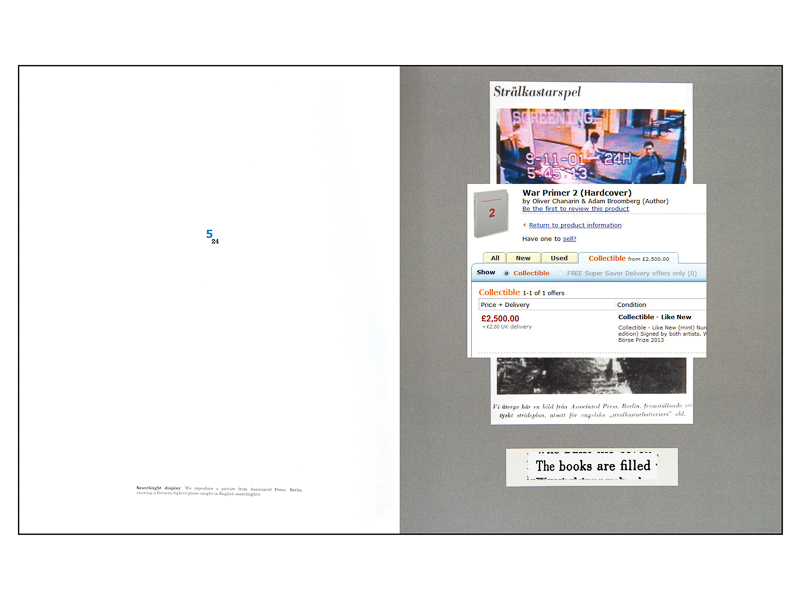

Their War Primer 2 is a case in point, updating Brecht’s original by inserting new material to provide a commentary on the connections that might be established between historical circumstances and the present; the message seem to be that, living under capitalism, some things never change. But War Primer 2 also highlights the contradictions of Broomberg & Chanarin’s practice, producing ostensibly ‘critical’ statements that are also luxury objects for a market that mostly shares their liberal world view – in effect, preaching to the choir. It is this contentious issue that Lewis Bush took as the impetus for his own adaptation of the project, War Primer 3, being an appropriation of an appropriation (of an appropriation, seeing as Brecht took the photographs in the original from a number of mass media sources). He has recently released a new, revised edition of the book along with a digital version and it is this particular format that will be the focus of my attention here. In its initial incarnation Bush’s War Primer 3 was conceived as a direct response to Broomberg & Chanarin’s update and as such had a more limited resonance, trading on an insider reference. Specifically, he highlighted the incongruity of a work that among other things satirised exploitative labour practices utilising unpaid interns in the production of an expensive limited edition.

Bush is of a generation that sees the limitations of socially engaged photographic practice and has been consistently creating projects that look beyond these limitations, to a sort of ‘extended’ photography, utilising the medium, but also acknowledging that pictures themselves are not always enough. As with Broomberg & Chanarin, the level of commentary often extends to an interrogation of photography itself and in War Primer 3 this component is certainly prominent. Brecht himself was acutely and presciently aware of the role photography played in propaganda; part of the original War Primer’s effect was calculated to expose this role by pairing found images with his own captions, which were often savagely critical. Bush’s version takes the interventions by Broomberg & Chanarin a step further by adding another layer of imagery that reflects back on the continuing relevance of the original and which also serves as a platform to question the somewhat self-congratulatory posturing of War Primer 2 as a contribution to a debate around labour that paradoxically falls into a version of the same deficiencies it was intended to parody. In its latest and presumably final incarnation, however, War Primer 3 is also directed more towards wider realities rather than those instances where they impinge on the art world.

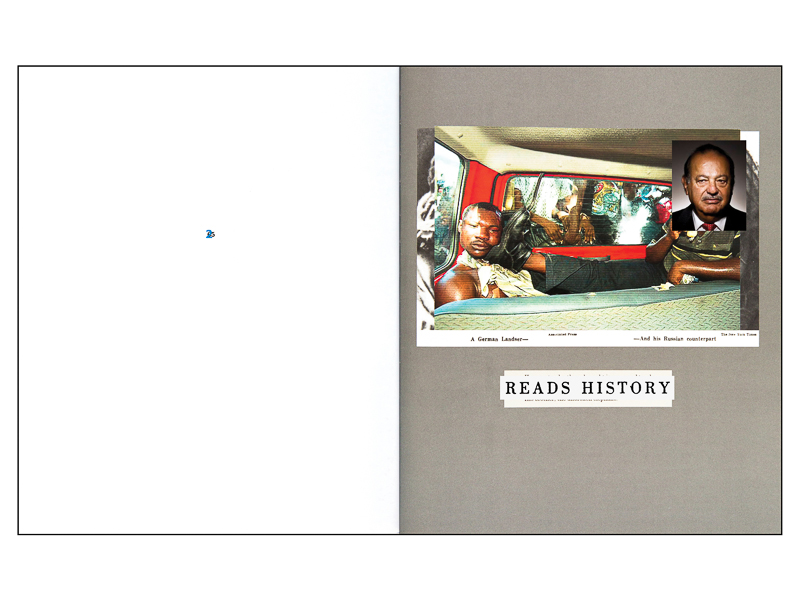

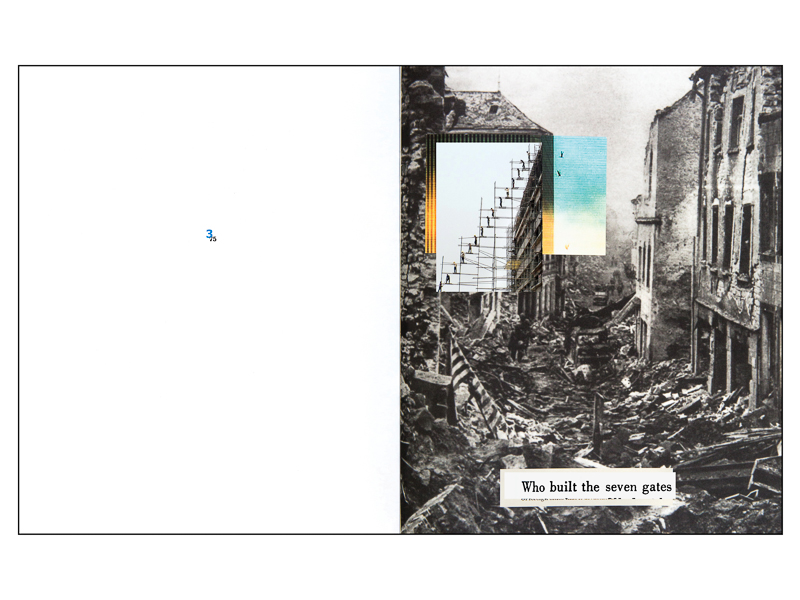

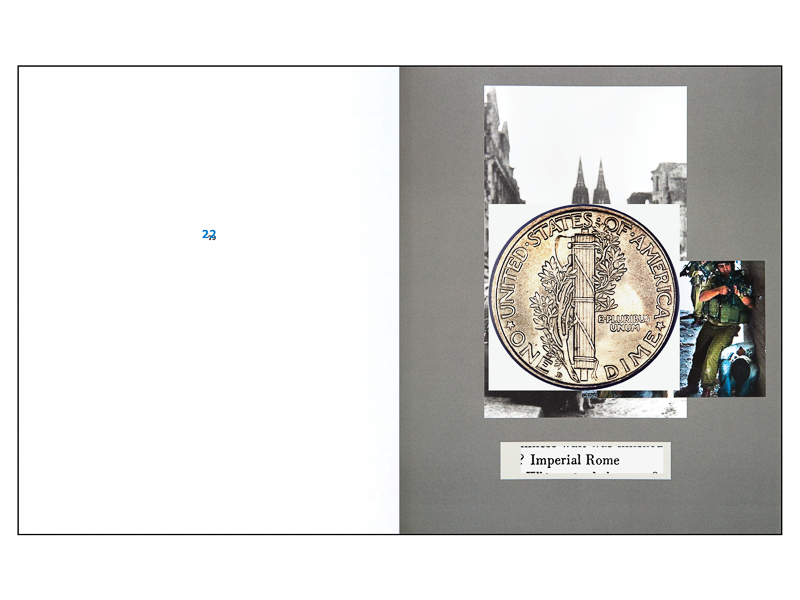

As a result, the impression that the images give is of a vicious circularity between the machineries of finance, politics and finally, warfare. These once ostensibly separate realms have become fatally linked and the mindset of near permanent crisis that seems to have defined this machinery in recent years is not seen as an aberration in regular functioning but appears instead as the very condition by which it continues to operate. The key to Brecht’s original vision was the complicity between big business and the totalitarian state, but the capitalism of Brecht’s time is certainly not ours and the historical situation in which he was working is almost wholly unrepeatable, so in that sense what matters here is less the specific content of the earlier images and the text as the method itself. Yet the overlay of the images suggests that present conditions are at least implicit in the historical situation they evoke. Brecht remains in Bush’s version as an echo beneath the later additions of Broomberg & Chanarin’s and to this extent it appears that his world constitutes the foundation of ours.

Bush is releasing his War Primer 3 as both a conventional paper book and as digital publication, which is free to download from his website. This must be at least partly a reaction to the state of a market that thrives on an artificial scarcity and a recognition of the fact that it would be impossible to comment upon the larger scale varieties of this model (i.e. the ‘real’ economy) while also participating in one of its more prosaic elaborations. The other advantage is of making the work available to an audience that if it isn’t exactly wide is still potentially wider than the number of people who will actually buy the physical book. This approach is in keeping with Bush’s understanding of the changed ground on which contemporary photography stands, an understanding that has also fuelled his prolific work as a critic of the medium. The traditional vocabulary of engaged photography just won’t suffice because the world has shifted too much for its assumptions still to be applicable and for Bush this necessarily applies to models of distribution for photography as well.

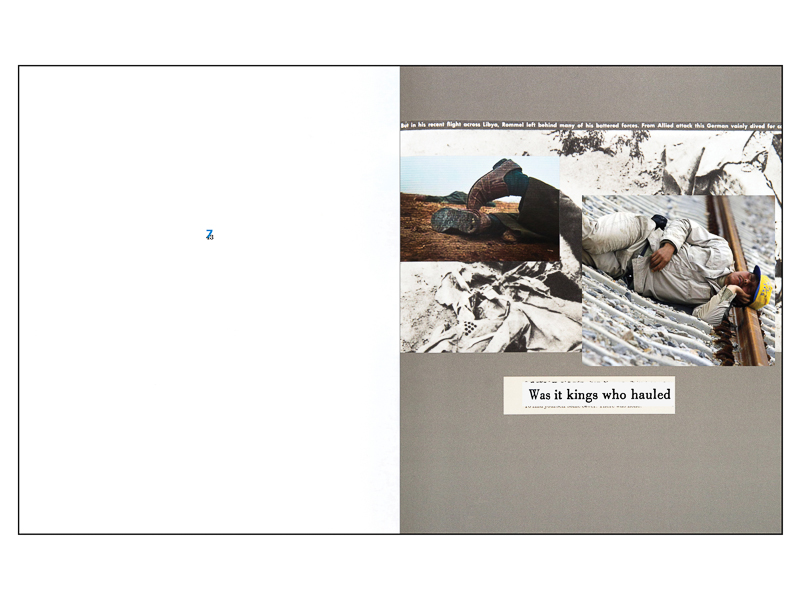

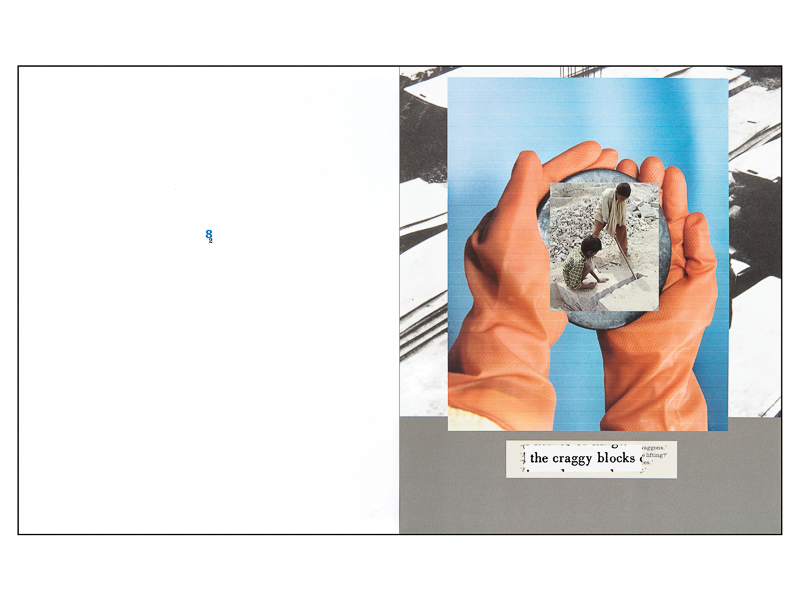

Aside from the specific references that the newly inserted pictures make (the notorious Foxconn appears more than once, for example), the cumulative effect of the imagery is to create an impression of the present as a ruin that grows relentlessly in front us and to which we are held captive. The layered arrangement of the pictures, beginning with Brecht’s originals, visually reinforces this idea of accumulation, which now seems to have reached a dizzying pace. What they attest to is the ‘progress’ of unstable social institutions and economic inequality. This situation is the result of an inability – or unwillingness – on the part of governments to counter the volatility of international markets, a reluctance that stems at least in part from the ways in which they benefit from it; Brecht’s old complicity has been enshrined at the very heart of our political processes. What remains as a subtext here is how much our present circumstances are the product of successive reactions against the failure of state institutions to stabilise post-war growth, a trend that actually begins in the early 1970s – and continues up to the present, with the latest economic crash.

The use of text throughout the book is striking, sometimes producing an intentionally confused, unreadable babble and at others a sharply pointed note of commentary. Each particular group of images is played against a short fragment that continues from one page to the next. This is Brecht’s poem A Worker Reads History, which is, essentially, a meditation on absences, on the names and roles of those that history – a history of great men and their works – has excluded. This is in keeping with the polemical rather than analytical force of Brecht’s writing; his concern for the revolutionary potential of the proletariat was something of an anachronism, even when the poem was written. Such ‘classical’ Marxist attitudes, mediated through events in Russia, are now as defunct as classical liberal capitalism itself and at any rate Brecht was never the most sophisticated political thinker, but his questioning in the poem remains its original sting largely because those absences have a continuing, often brutal reality. The difference for us, as Bush points to here, is that the workers no longer just provide great monuments, but smart-phones; the pattern of production and consumption has become so diffuse that it constitutes the unacknowledged fabric of our lives.

What War Primer 3 demonstrates is the fundamental continuity of economic exploitation and political oppression that now appears as the hallmark of contemporary social organisation. As more and more people are pushed to the margins, inequality becomes the new normal. If we have moved towards a model of society based on the prerequisite of control, then a lifetime of indebtedness, set at the whim of a globalised marketplace, becomes a key agent of that control. While Bush’s modest and actually rather restrained book never veers into agitprop sentiment, there is still a core of real anger at the heart of it. Beyond this, it points also to at least one avenue for thinking about a contemporary and socially engaged practice in photography, as well as for how that work might be distributed in a more open-ended way. That in itself is an important contribution to the evolving conversation around the medium, though it may still fall into the trap of speaking to an audience already aware of its concerns. In that sense, the purpose here is not to effect change, but rather to understand the conditions by which it might still be possible and in that Bush’s War Primer 3 succeeds admirably.