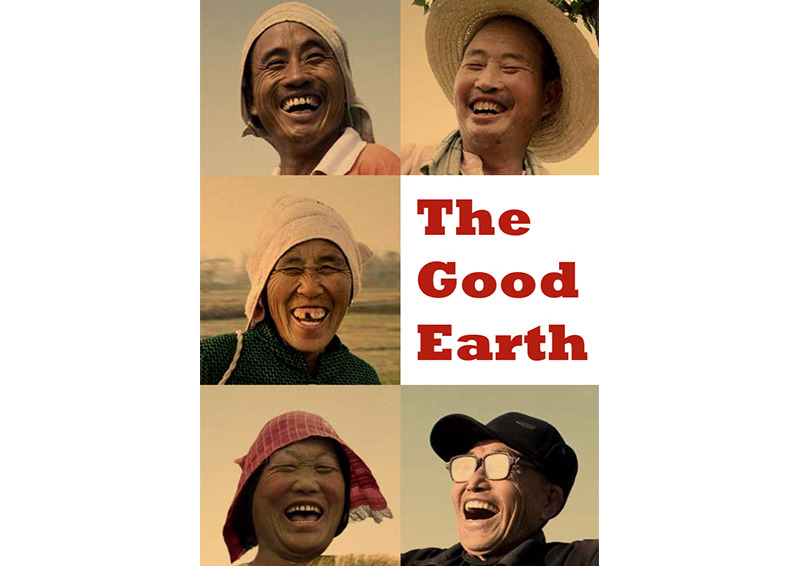

Li Kejun’s The Good Earth, selected by Daniel Boetker-Smith

THE GOOD EARTH by Li Kejun (88 Books, 2012), BUY

Li Kejun’s book The Good Earth represents for me a moment when the true possibilities of the photobook became apparent, I had just launched the Asia-Pacific Photobook Archive (based in Melbourne, Australia) and I received a batch of books from Ho Tam (Director of 88 Books, based in Vancouver) who was slowly publishing the work of a group of largely unknown Chinese photographers in a series of small monographs.

The Good Earth is slight in weight, small in size, simply printed, and very basically bound with a couple of staples – but it represents a voice so clear, a vision so evocative, an intelligence so acute, and a consistency that is so engaging that none of the pragmatic concerns of book production matter. It is a perfectly formed masterpiece of just 24 pages.

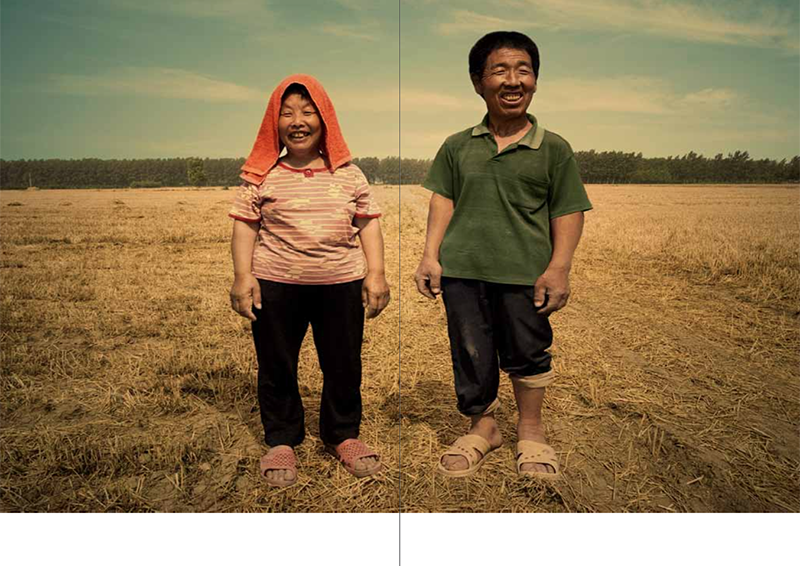

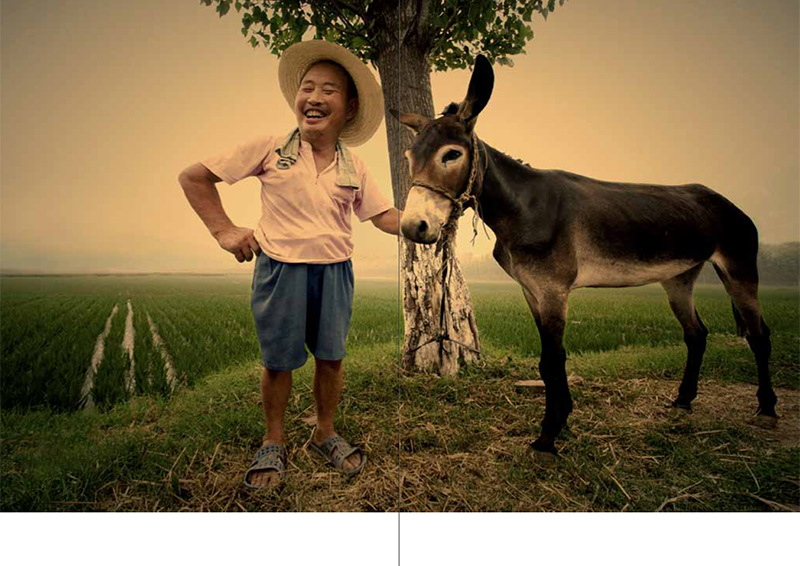

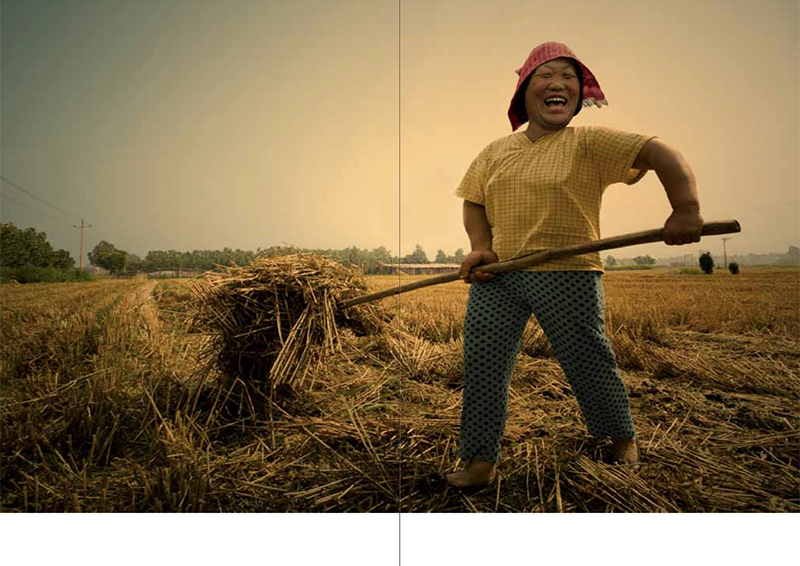

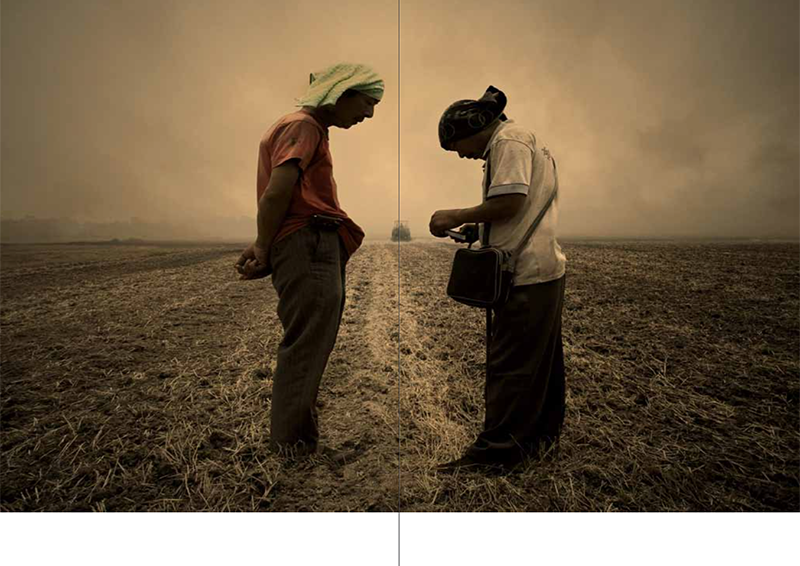

Kejun’s work takes its visual clues from traditional Chinese cartoon characters, but deals with a serious and important topic that has attracted a large number of both Chinese and international photographers in recent years, the rapid economic development and urbanisation of China. Kejun’s images, put simply, are of Chinese farmers (both male and female) laughing; and the effect of the book is akin to the infectious nature of laughing itself, once someone next to you starts its hard not to join in.

Kejun takes our expectations and turn them upside down, we think we know China, we dont! He is not trying to encapsulate the whole of these people’s lives into one image, nor is he trying to instigate change, nor is he reporting about all the hardships and disappointments that these people (surely) suffer. Instead he steps forward into their space, and joins them in a celebratory moment, they are alive, they love, they work, they feel, they breath, and most of all they laugh. The simplicity of this project is its strength; it is well and truly a performance, a show, and one that sorely needed as we move more and more towards a global urban monoculture, Kejun is trying to balance the scales. Kejun’s work reminds me of Raymond Depardon’s most wonderful Modern Life documentary film (2009) that focused on the idiosyncrasies and humour of rural French ‘folk’ but with a central theme of pathos and loss. The Good Earth has this same sense of pathos, there is a sadness here, but the sadness for me emanates more from the fact that stories like this from China, and other Asian countries too, are so rarely seen and rarely told. Kejun’s agenda is educate us as to the complexity of life, a universal truth.