Marianne Bjørnmyr – An Authentic Relation

all spreads courtesy of the artist

AN AUTHENTIC RELATION by Marianne Bjørnmyr (self published, 2016), BUY

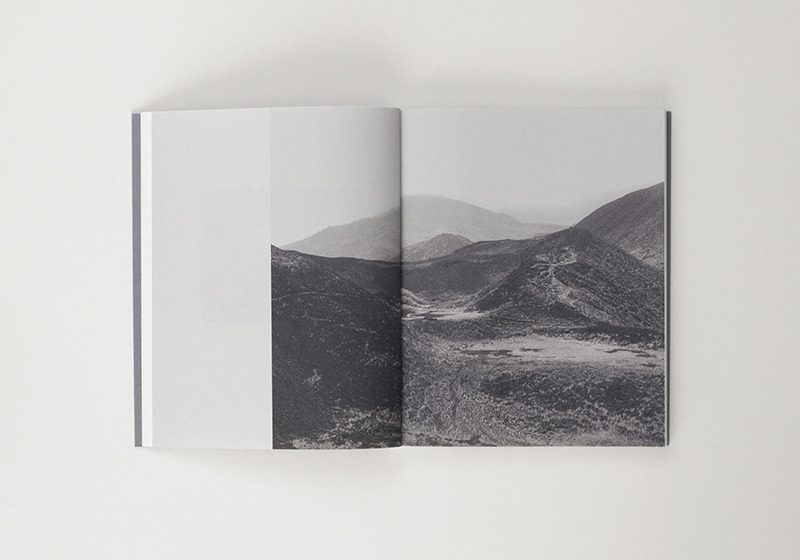

An Authentic Relation by Marianne Bjørnmyr presents photographs from a journey the artist made to Ascension Island, accompanied with Leendert Hasenbosch’s original diary; a constellation of documents and images, culminating in an overall feeling of distance and displacement, questioning our idea about history, not as fortified facts, but as possible fiction.

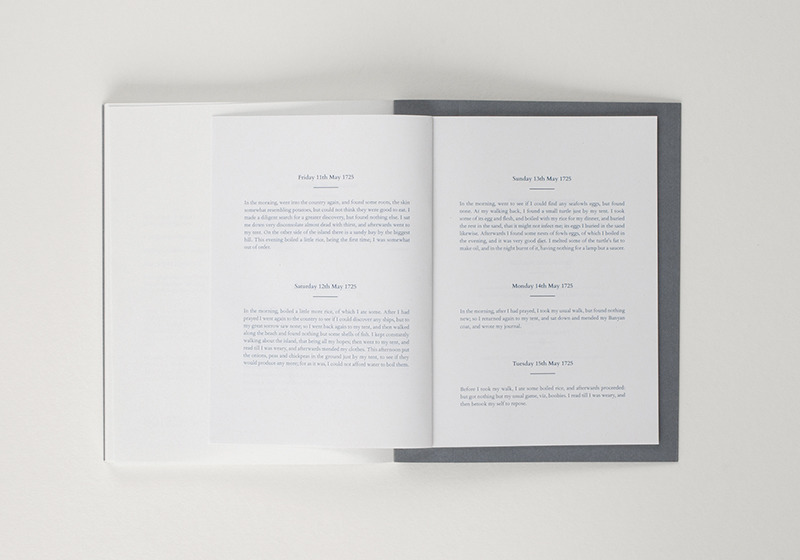

Sent to the shores of Ascension Island in 1725 as punishment for sodomy, after six months Hasenbosch tasted his last bit of turtle’s blood. He was first a Corporal and then a Military Bookkeeper aboard a ship in the Dutch East Indies. During the six month prelude to his death on the island, Hasenborsch kept a diary. In January of the following year, British sailors allegedly discovered his tent and belongings, including the diary, although no sign of his body was ever found. Much has been written about what happened in those six months between Leendert’s sentence and death, including three published versions of the diary with varying degrees of poetic license. It is unclear which one is accurate (if any are) as the original diary has been lost.

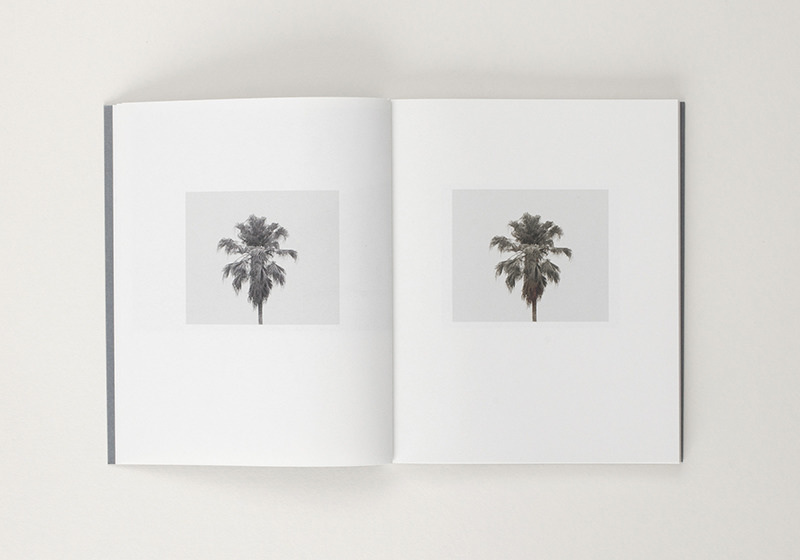

To see the world through images is to place in front of our eyes the filter of memory and in some way to privilege the archive, not the reality it reflects as the space of experience. In this light, the images within An Authentic Relation are a reflection of a memory. We do get access, through the pages, to an impenetrable world, composed by different fragments from the same story unified by photography and text but separated by history and time. This idea reflects the design of the photo book where the text lays in the back, away from the images and can be removed or rearranged; existing side by side but not together. The intention of Bjørnmyr is clear: images repeating themselves throughout the book, in obvious or less obvious ways are organised in an intertwined net of echoes and references. The net is forming a priori condition of the perception itself, and without experiencing it themselves, the viewers perceive the story and makes reference to the events.

The passage of time is conceived by altering our notions of truth and reality. The very stillness of a photograph is unnatural, and creates for the viewer a sort of fascination; it suspends the unceasing march of time into moments of frozen details. The clear and apparent gets obliterated, the viewers navigate through the story independently, creating their own cartography of an abstract narrative and form a vague story solidified through the image.

For the photographer, there is no choice between document and fiction. We live in a tangled web of fictions that prevent us from getting back to the starting point of our reality. In Platonic terms, no one can leave the cave and we must make do with the world of shadows. It is those shadows that allow us to structure our experience of reality.

Bjørnmyr’s journey through the book is an exquisite exercise in storytelling and at the same time shows that photography can be both registration and writing. With these fictional representations, Bjørnmyr increases the flexibility of our imaginative capacity, leading us on a journey where photography is a fragmentary form of story. In terms of history, the interpretation of these images shows that photography, with its dual nature, notarial and speculative, is both register and fiction. That one of these facets was then banished as subordinated to the canonical documentary mode can only be excused by the dominance of scientific culture and its associated values such as empirical positivism. The camera not only imposed a certain aesthetic on the way the world was configured but in fact photography encouraged a new stage of historical consciousness in which new ethical categories such as rigour and objectivity sanctioned moral values such as truth and memory.

The meaning of an image is built up by an interaction of signs and a composite of codes, more to be compared with an elaborate sentence than a single word. Its meanings are multiple, concrete, and, most importantly, constructed. Can a personal authentic relation with history exist? Could photography be made to speak above and beyond the surface appearance of reality? Marianne Bjørnmyr suggests with An Authentic Relation that culture and history might be constructed, and because our ideas of reality are entirely dependent on culture, reality is also constructed. However, her vision does not deny the personal emotion and unique viewpoints of the photographer, the sanctity of the individual artist’s vision and originality.

Marianne Bjørnmyr launches An Authentic Relation on Tuesday 23 August at The Photographers’ Gallery