Matthew Leifheit – Fire Island Night

O brilliant kids, frisk with your dog,

Hart Crane, from “Voyages”

Fondle your shells and sticks, bleached

By time and the elements; but there is a line

You must not cross nor ever trust beyond it

Spry cordage of your bodies to caresses

Too lichen-faithful from too wide a breast.

The bottom of the sea is cruel.

Res: How do you feel?

Matt: Well, this is really the most time I’ve spent on a body of work so of course, it makes me nervous to see it all up on the wall, but there are some more pictures I want to make on Fire Island in the winter, so it gives me some comfort there is more work to do. Eventually, I’d like to make a book or something.

When did you start this project?

I started right after we graduated from Yale in 2017, and at first, I wanted to figure out a way of working in colour that could be expressive. I had been making very dark, low contrast black and white photographs in school, and I always want the style or the way the picture is made, to be part of the meaning. I spent that summer taking photos of sunsets, which was therapeutic but it was also a way of making colour studies. Those pictures were all garbage. Then there was a shoot late that summer, where my friend Hudson Bohr asked me to photograph him and his boyfriend together because they were moving to different cities. I liked the idea of sad, commemorative nudes, and we shot them outside on a day when it was raining. The sky was so dark and the film was very underexposed; all you could really see was a gleam of light in their eyes. That established a tone for the rest of the work.

Walker Olesen, our mutual friend and classmate, told me early on that I should find a way to expose the negatives so all the information was there, and print them down instead, but to me it was important since there is so much black in these pictures that the information actually isn’t there on the negative; there is something lost. It’s related to desire or longing, which always involves something missing.

A lot of photographers fear the loss of the image, but you embrace it. Out of all my photographer friends, you’re the least concerned about failure. There is also something about embracing the loss, or the chaos; which, with all the advancements in technology, it’s almost about the exact opposite; the attempt to make it perfect.

Well, of course, I think that’s trying to control something that’s just uncontrollable. Part of what I love, and maybe the greatest power of photography, is that you could catch something. And I think the failures and the technical eccentricities are part of that. Something that isn’t planned but often more interesting than what I could have imagined.

I think the slippages and the material evidence of the film is like a fingerprint; it’s the only way to know it wasn’t taken on an iPhone. You can almost touch it.

In an interview with Vogue Italia on your series Güerxs, you quote Robert Adams from Beauty in Photography, “Why is Form beautiful? Because I think, it helps us confront our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning.” Out of your work, I think this series is the most chaotic. Do you feel like you’re trying to make logic out of the chaos? Even in terms of form—the risk of underexposure, the light leaks, not to mention that you’re making them in the dark doesn’t seem like you’re trying to tame the chaos. It seems like you are inviting the chaos in.

Well, even on a technical note, a lot of the photos were taken with a 20mm lens, which is very wide and you simply can’t plan what will happen in the frame when you use it in the dark. Cameras record the surface of everything, and I’m working in the real world as opposed to the studio because it offers something more in terms of chaos. The chaos of life is more interesting to me than photography’s potential to tame it. But I do very much believe that aesthetic beauty can be powerful.

You worked collaboratively with Cynthia Talmadge in the studio, but before that, your work has always been involved with documentary.

I have worked as a photojournalist occasionally, so I have a relationship with that. I still think the relationship of a photograph to reality is what makes the whole thing worthwhile. Fire Island is not only a fragile ecosystem but also a place that I think is undergoing a transition culturally, so it feels useful to record it. And I do think the pictures are documentary in some way. Even though everyone in the pictures agreed to be photographed, aside from the ones at the underwear party which are totally candid.

But maybe we should talk about why you went there in the first place. Because you went there before on assignment, and it’s interesting to look at those pictures in comparison to these.

I first went to Fire Island on an assignment for VICE in 2014. I went with a writer, my friend Mitchell Sunderland, who was covering the underwear parties. I had never been there before, and I used a digital camera with a flash to make quick observations; I was only on the island for two days. But that’s the first time I went to the Belvedere, and the first glimpse I had of this world that I fell in love with, which I thought had died in the AIDS crisis or something. It was a culture I hadn’t experienced and had only read about in old novels. A very hedonistic, homosocial world of sex and decadence, which in fact is very much still alive in certain places.

I also did a lot of research about George Platt Lynes when we were at Yale, in his archive at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. He went to Fire Island and appears in a lot of the PaJaMa collaborative photographs that were made by Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French. The landscape in those photos looks like such a canvas for surrealism, and they made me want to return.

I had applied to a residency on the island that I didn’t get, but I was determined to make a body of work there, and after a studio visit and conversation with you last spring I decided to just go there and find a way to do it. Actually, the place where I ended up staying in for 3 months, as part of a self-constructed residency was called Oakleyville, a small community of ten or so shacks two miles into the dunes where Peter Hujar and Paul Thek used to go in the 1970s. My friend Marcelo and I went looking for body parts because apparently, Thek made some of the life casts for his “Death of a Hippie” self-portrait in Oakleyville, and neighbours were finding fingers and hands and so forth. It was like history was waving at us. I met a very generous woman named Ency Baxter, whose mother had rented the house to Hujar in the 70s. She liked the idea of someone staying there who knew the history of artists on Fire Island and gave me the keys. It was very romantic from an art historical perspective, to be there mostly alone all summer with those ghosts. It also meant that each time I did a shoot in one of the gay communities I had to walk at least two miles through the dark sand dunes with all of my equipment.

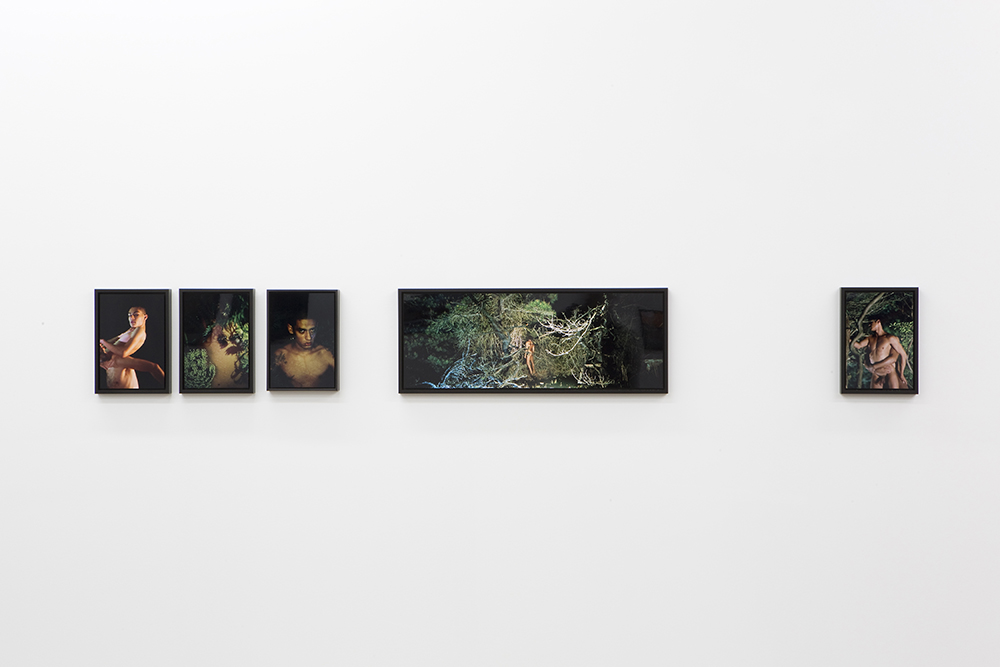

Installation of Fire Island Night at Deli Gallery, 26 Oct – 2 Dec 2018. Photos © Deli Gallery.

You’re speaking about the work in a very literal way, but to me, it’s more metaphorical. I know you’re interested in poetry, and you’ve worked with the poet Susan Howe.

I met Susan through the Beinecke, where I was doing a fellowship in 2016, and they were in the process of collecting her papers. I worked as her assistant for a while during school. But I had admired her work before I met her. She’s someone who seems consumed by history and by what kind of things get written down, and exactly how they are written. Susan was the first to tell me about the early American feminist author Margaret Fuller’s drowning off Fire Island in 1850. I made a lot of pictures by moonlight of the site of her drowning so that I could report back to Susan. I do think of the pictures as a sequence or a syntax of images, something more like language.

Even the way you’re speaking about it now is in very literal terms, “I was assigned this and brought it back” but to me, because I visited you out there, it’s not the world of Fire Island in its current totality. Cherry Grove and the bars around there have some of the elements of a tourist trap, it’s more contemporary looking. I feel like you’re speaking literally when it’s more about metaphor than anything else.

I don’t mean to be unforthcoming or anything, but I do love when you see a book of Robert Frank or those guys from the 70s where the information they give you is, “I used a Leica and these lenses with this film to take photos in these places on these dates.” There’s a frustration of, this is a very psychological image and you’re describing it in the most literal terms, but it also leaves room for a lot of mystery.

I think all of us who decide to be photographers, find comfort in the idea that the world gives us the material to make something up. I’ve always been seduced by the possibility of a world of my own, completely of my own making. Of course, that’s never the case…

It’s always a collaboration with the world that exists…

And we’re all products of the world that we’re in. But there is something about this body of work that feels completely of your own making. At the same time, there is so much history involved in the work. But could we go back to why you chose Fire Island?

On one hand, it’s this place that is going through a transition. As definitions of queerness are expanding, I think about what the usefulness of a male-only, clothing-optional guesthouse like The Belvedere might be, as people have less use for gender boundaries. I see it as a place that was created by a previous generation when people had to go to geographic extremes to express their sexuality, and now when people can be openly gay in more and more places, I wonder how its purpose will change, and what the visual evidence of that will be. So I’m interested in these gay vacation destinations because they exist as a fantasy of escape, and particularly an escape to another time. And you’re right, it is very much my own world that I’m trying to create in the photographs. But it’s a fantasy world constructed out of the facts of that place.

In the pamphlet of text and reference images that sit alongside the show, there is a map of the way the island eroded during Hurricane Sandy. Like all things in your work, we can anticipate its loss.

Like Miami or Venice. Part of my interest in photographing on the island was also the tiny forest, used as a cruising ground, which is endangered like the dunes and largely made up of tiny, twisted holly trees. I wanted to record that landscape, which is the first time I’ve even tried to photograph a landscape in any way.

And you were like go wide or go home?

Yeah, I used a panoramic camera, which basically does two frames of 35mm film at once. I also looked at Pierre Puvis de Chavannes paintings at the Met; I had gone to see Eggleston’s show of “Los Alamos” and was kind of bored by it, but there were these long paintings in the hallway outside, studies for murals I think. Many figures arranged onto a long skinny horizontal canvas, and I was excited. It was like a stage, and I thought about a film format that could suit this kind of composition. But I never wanted to use it for landscapes, which felt like the conventional way to use this kind of format. In the end, I included a couple of seascapes taken by the light of the moon that were made this way.

You decided to embrace the possibility of failure. What is the significance of the sea and the sand and the fire? What histories are held in these artefacts and the things that were washed up ashore?

I saw this Joan Jonas retrospective, and the way that she uses the elements really inspired me. The way she shows the elements—the way they wear on people and things over time—I find very powerful. Since the island is actually changing shape with the tides, I wanted to use the elements to show the effects of time.

But how significant is time really, when the pictures are all at night?

I want it to look like an endless night. I want it to be like the shattered pottery fragments I collected on the beach over the summer, some kind of shattered vision of this world that can encapsulate both the present day and different facets of the island’s history. Most of the work I’ve done previously included archival pictures I researched or curated, and in this work, I really wanted to figure out a way for the history to be encapsulated in the way I am looking at the place.

In most of the pictures, there are very few signifiers of the contemporary moment. The spaces we’re looking at, are the Belvedere and the Ice Palace, when were these built?

One in the late 50s and the other in the early 70s. I feel like they’re not only symbols of a previous generation of queer history, but they are a part of gay male history. Fire Island Pines has a reputation for its history as a commune of cis-male affluent muscle gays within the gay community, although thankfully those standards are changing. I mean, Cherry Grove has a strong population of women. But I also feel like much of the symbology I’m working with—like the Belvedere where women are actually not allowed—is from the history of fags, and not necessarily queer as I understand the term. I think this history is important to preserve but is also worth questioning.

Yes, and it’s only recently occurred to me that we are the children of the AIDS epidemic. It began at exactly the time we were born into the world, the time when all of America and even those who were living the most radical lives, were confronting this harsh reality of death at a young age and related to sexual freedoms they’d only recently gained. That freedom in the 70s led to a lot of good art. Maybe I’m romanticising it but even the best porn comes from that time. The floodgates were open and then suddenly came crashing down. That’s a lot to happen in the span of 20 years.

Well, Larry Kramer’s book Faggots sort of prophesied the negative effects of that era of free love and promiscuous sex in the gay community. But I also think that now, because of PrEP, I’m seeing a resurgence of this kind of hedonism that I associate with another time. It seems like every gay guy I know is not using condoms and is on PrEP, which has allowed for less inhibited sexual practices. I feel like it’s this new era of gay hedonism and I expect it will have its own challenges alongside its joys.

It even did back then. Part of what Fire Island holds is that it wasn’t everyday life. People would go out there for crazy wild weekends and have to come back on Monday to get shots for whatever STD they’d contracted. There’s something about Fire Island as this place you go to for one night, and that night has to hold everything.

How might that relate to “forever young” or these stereotypes of gay male existence? This desire to fight off death or never grow up? It’s like Never Neverland. I think that’s part of the gay imaginary.

It’s funny you should say Peter Pan, I was thinking of Pinocchio, of Pleasure Island, where bad boys turn into asses. Fire Island is a place that exists for a lot of people largely in the imagination. Asking another man in New York if he is “going to Fire Island this summer” is a coded way of asking if he is gay. There is this culturally shared fantasy, so I’m interested in that as well.

But is it a fantasy of yours? If you’re thinking back to the 70s or back to these other times, what is it to you now in 2018?

That’s a hard question. I feel like hopefully the answer to that question is expressed in the images in a certain way. I think the way that I feel about the place based on my lived experience of it, is contained in the way I’m looking at it with the camera.

I think it is, even more than it has been in the past. I know your work very well, and the Yale Daily News project that you did in school where you sort of stepped into the role of a news photographer for the school newspaper, and Collier Schorr calling those pictures “anti-news.” You were more interested in the outtakes, specifically those that were creepy, sexual and dark. That part has carried forward into this work. I feel like this new work is also about a place, but it’s a place of extremes, of the highest highs and the lowest lows. It doesn’t hit the middle ground. The fire and the water. What does the water mean to you?

Well, a lot of queer artists love water.

Like who?

I don’t know, Roni Horn, in her project Dictionary of Water, one of my favourite bodies of work, which is also very dark because she photographed the Thames where people often commit suicide. Peter Hujar did those very psychological pictures of the dark water of the Hudson River. One of my favourite Félix González-Torres works is one of his stack pieces, an image of the surface of the water that you can take home with you. Eakins even. I think it’s the darkness of water that attracts queer artists to it as a subject, but also the way that it changes shape and alternately reveals and conceals. It’s also widely written about in photography by Jeff Wall and Kaja Silverman and others as the one thing we can’t control.

Water is the thing we can’t control, not just in photography. It is what will become of Fire Island.

I read one article that said it could be underwater by the year 2100, but I hope that’s wrong.

I was thinking about the concept of the photographer working from the outside in. Someone who goes out in the world filters information and brings it back for the masses to understand. I feel like now in Fire Island Night, it’s almost gone the reverse way for you; you are working from the inside out. It is as though you’ve become a medium for a lot of what that place holds, and for a lot of gay artists who have worked there; it is as if the dead are communicating through you. I see you channelling artists who we lost too soon, Wojrarowicz, Derek Jarman, Peter Hujar…

I feel like that’s the previous generation of gay artists who I’m responding to. And they created amazing things but there is also this silence because of their absence. I feel like it’s easy to romanticise that silence, which you’re right, is around the time of my birth.

In the coded language of queer art that was made well before the 70s, where you couldn’t necessarily speak to your desire explicitly, the mystery in that desire becomes so seductive. I came into loving art primarily through the work of that age. It’s like the black in your imagery, it’s so much about what you can’t see. It is in the darkness that I find an emotional relationship with these pictures, in what’s not there, because those are the places where I have to pull from myself. So often the things that are the most meaningful to us are the things we can’t really describe. And especially in work that contends so much with death. No one can know death until it happens, all we can understand is the feeling and fear of loss.

I like what you are saying about code, because part of my thinking of installing the show this way, in a straight line or syntax of portraits and still lives and landscapes, was that it could look like morse code, or DNA test results or something. A lot of things in these pictures would mean something very specific to someone who knows a lot about the place or its history, but I also hope that kids or straight people or anyone could enjoy them on a visual level.

A lot of the images have people in them, but there are very few portraits.

Yeah, a lot of the people here are kind of acting out my fantasy, and I don’t think it’s necessarily about them. When I do a portrait I want the picture to be about that person, but in this case, the subjects are for the most part helping me carry out some kind of play. They are the real people who are on Fire Island; the location is the real place, and they are doing the things that happen there, so I think the pictures are documentary in some way. I am not willing to go into the cruising ground at night with a flash to expose and out people; I have to stage the picture to some extent to show what really happens there.

All of this is reminding me of the Derek Jarman film Blue which we went to see together. There is that part at the beginning with the doctor and the monologue about vision. Your first picture in this series is an eyeball with pinkeye, which I didn’t realise has significance in the gay community.—

Yeah, queens will make jokes about eating ass. But to me, that picture is about a struggle to see clearly. It’s a depiction of the struggle to see something the right way or truthfully with faulty, subjective vision. Inaccurate and diseased and fraught like camera vision.

This part, in particular, resonates with Fire Island Night, “But what if this present / Were the world’s last night”. In the context of Jarman, the night is something so much more.

Well as he was making that film, he was losing his vision to AIDS-related illness.

Jarman so eloquently describes his loss of vision, which for a photographer would be a kind of death. The meditation on loss and the darkness in this series is palpable especially in relation to gay culture and fighting time. In this work, you’re photographing something you perceive as slipping away. I recall a few years ago you sent me a text seemingly out of nowhere with a quote from Dorothea Lange. “One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you’d be stricken blind. To live a visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable. I have only touched it, just touched it.”

I think desire is the only thing worth photographing.

Matthew Leifheit, Fire Island Night, is on view through December 02, 2018 at Deli Gallery