Matthieu Litt – Horsehead Nebula

The lure of distant places and ways of life is, of course, no surprise; that the camera should be the ideal accompaniment for such treks into the unknown is obvious too, given that it provides both a rationale for the traveller and a vicarious means of bringing ‘exotic’ sights to the folks back home. While Matthieu Litt’s Horsehead Nebula doesn’t fall prey to the deficiencies of the travel photography genre, he remains gratifyingly aware of them, given his role as a photographer observing a place and a way of life that are, we must assume, far removed from his own. Indeed, how he plays with, resists and occasionally surrenders to the exoticising gaze of the photographer abroad, is one of the keys to understanding this work. Litt doesn’t even identify the place or places that he’s photographing. We might guess that it is one of those shaky republics on the edge of Europe, formerly a Soviet possession, or maybe he has travelled still further east, perhaps to the steppes of Mongolia. The narrative remains significantly open-ended; in fact, it’s more about the idea of a place than anything else.

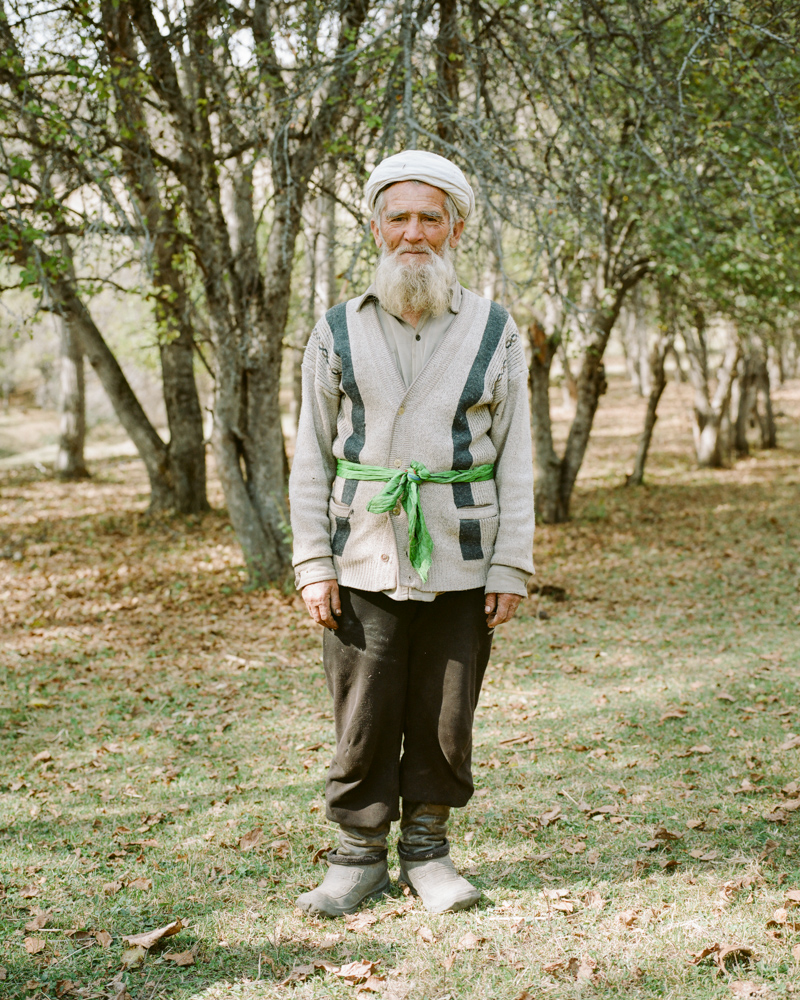

So while Litt concentrates on what probably are, when seen in context, fairly ordinary scenes, because here they are folded into the expectations that accompany viewing images of somewhere culturally and geographically distant, this fundamentally re-shapes our perception of them. Of course this assumes that the present viewer and their place in the world (white, western) is inevitably the norm against which other experiences, other places, must be understood; everything else is, in short, Other. To underscore the nature of this distance, we need only consult the title of the series, which positions Litt’s subject so far away as to be in a galaxy removed from our own, although there are admittedly other resonances to the title as well, connected in particular to the lifestyle and cultural traditions of his subjects. In fact, what the pictures assert above anything else is the particular continuity of that way of life; the thread of its history appears to have survived intact. The enclosed nature of that life, an apparent completeness, means that we (and Litt) must remain cultural voyeurs.

Against that however, is the resolute attention Litt pays to the incidental character of this (largely imagined) place, its daily textures and shadings. In effect, he builds his narrative around these rather unspectacular details, so that the more picturesque elements – such as traditional costumes, and even the showy grandeur of landscape itself – stand out in sharp relief, but are at the same time decidedly undercut by the presence of images that run counter to these mythical set pieces. There is no contradiction in the fact that we call this an ‘imagined’ place when the picture he provides of it is based on the accumulation of so much concrete detail, because while it is admittedly not any one place in particular, it is in fact a composite of places, subsuming a single idea of place as always being somewhere else, somewhere beyond the limits of what is known. Such places have a tenacious hold on the imagination, we continue reaching out to them even knowing that are unattainable or that they are fatally compromised by the incursion of reality.

Not specifying his destination reminds us that it is, by necessity, an ideal that can’t be realised in practice; all such ideals are built on the mundane reality of places composed of stubbornly real lives and histories, the same details that Litt is so attentive to. The other effect of this reticence is to challenge the potential exoticism of his subject matter, even as he brings us – forcefully, if subtly – back to our persistent fascination with the Other. By playing with our expectations in this way and also, though not incidentally, creating a genuinely sympathetic portrait of this place, wherever it is, Litt offers an alternative route out of the deadlock of a photographer pursuing an age-old fascination of the medium, one that has begun to seem increasingly burdened by its own ugly heritage. By contrast, Litt’s pictures are light in a way that can at once acknowledge his (and our) role as interloper, without sacrificing any of the often magnetic pull that other cultures – and not just the culture of the Other – continue to have over our imaginations.