Raymond Meeks – Halfstory Halflife

Raymond Meeks, Halfstory Halflife, Chose Commune, 2018

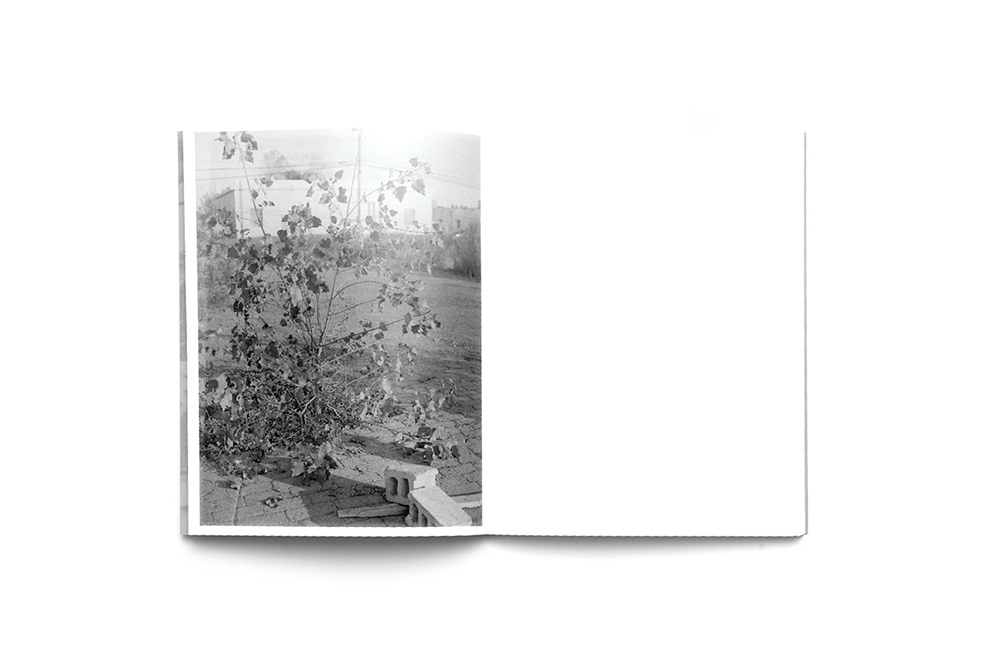

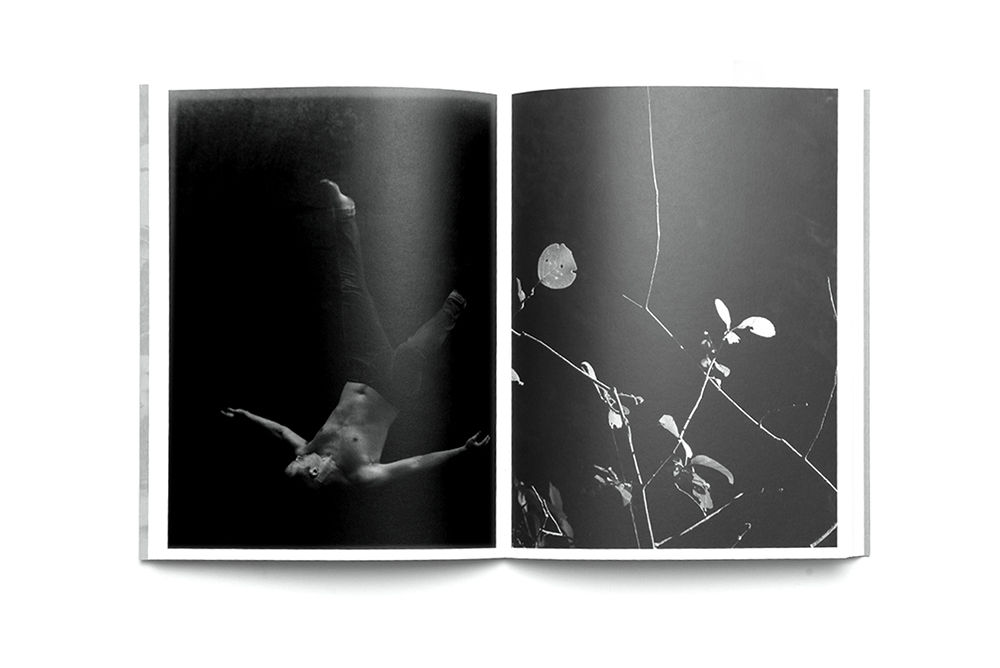

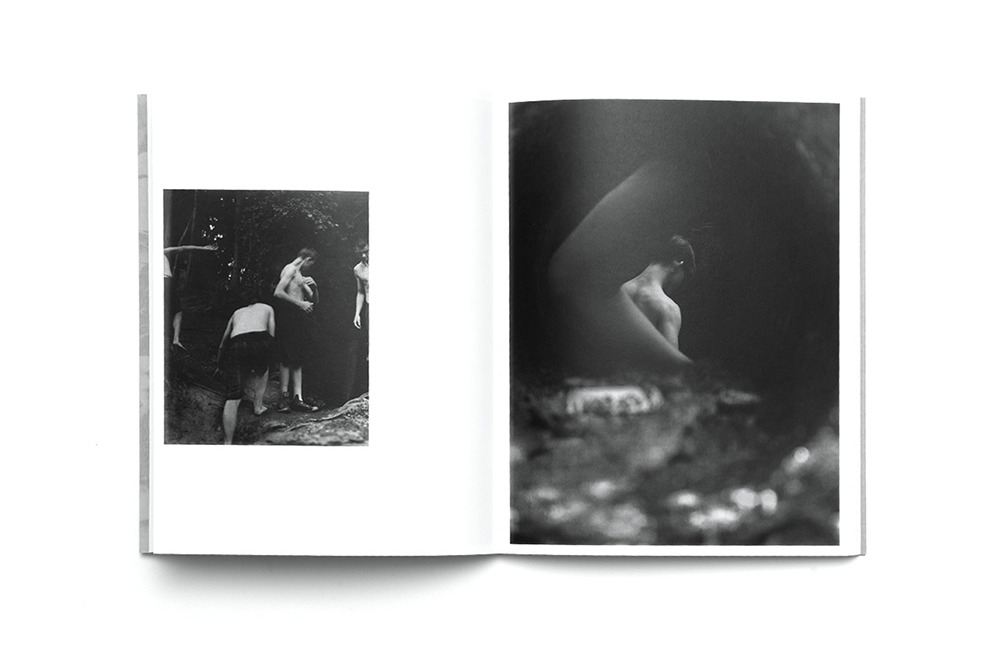

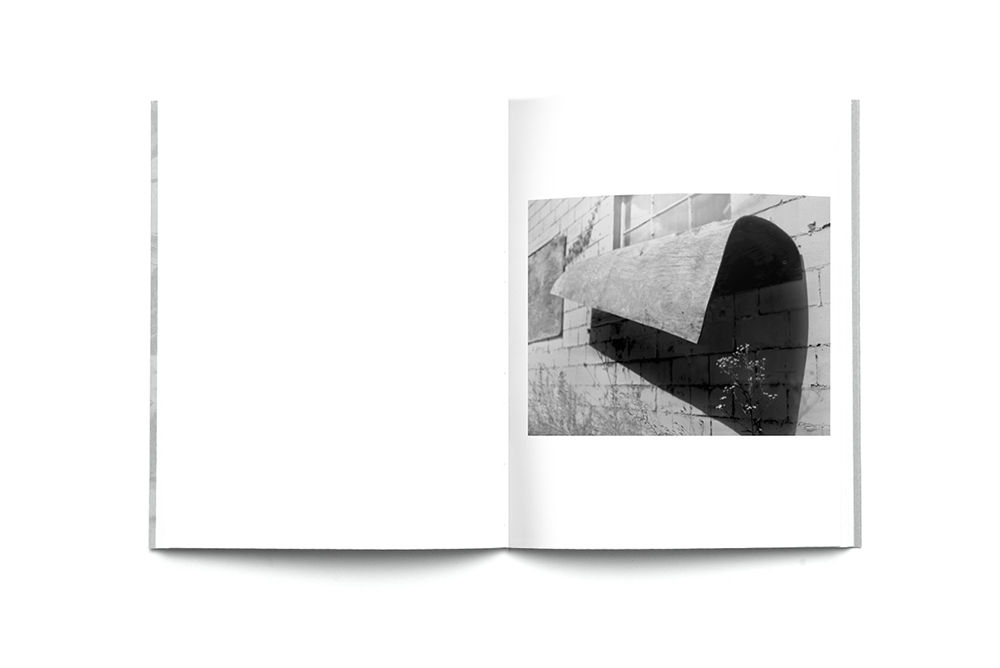

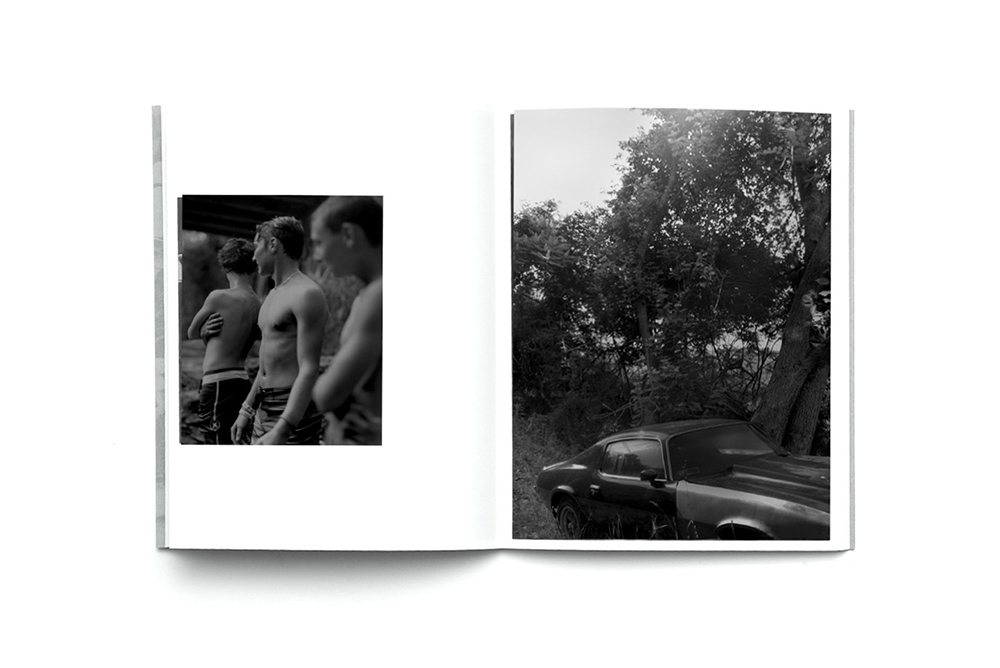

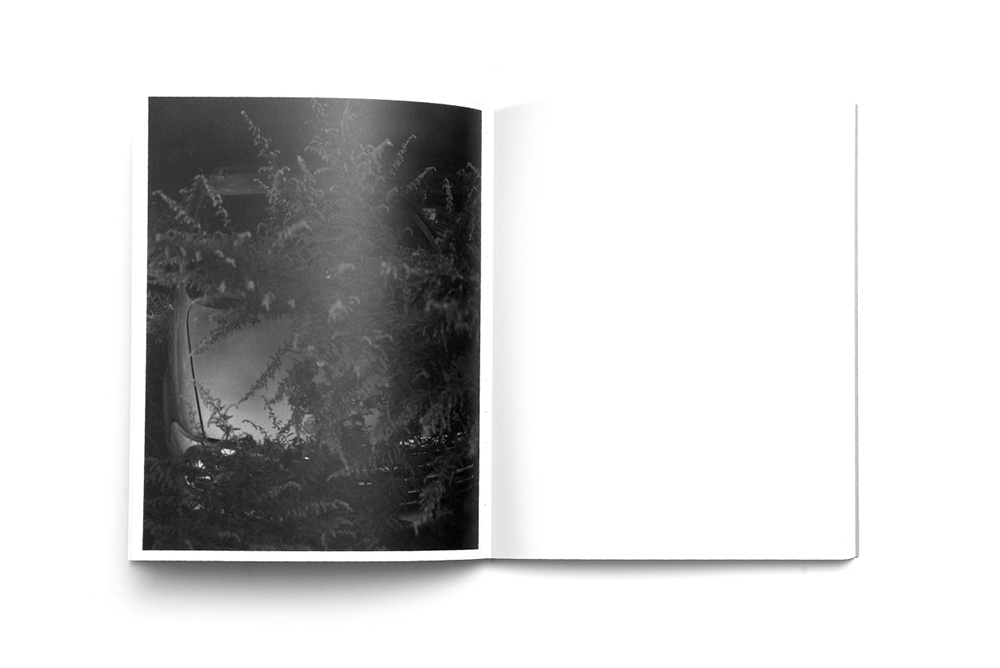

With limbs waving wildly, an untethered male body plunges headlong into a forbidding darkness. It is an act that American photographer Raymond Meeks has documented over multiple summers, and serves as the subject of his new, and widely-acclaimed, book Halfstory Halflife (Chose Commune, 2018). A few miles from his home in the Catskill Mountain region of New York, a waterfall towers sixty-feet over a moss-lined creek bed. Here, the local youth gather in numbers, one-by-one launching themselves into the charcoal abyss below. Left behind is the modern world, defined by its worn and fractured tarmac and vacant cars abandoned in dust-strewn lay-bys. Wandering up trodden footpaths, cutting through layer upon layer of overgrown foliage, these young men journey back to a place from time immemorial. It is a return to nature, and ultimately a return to the self.

The images of Halfstory Halflife ebb and flow, alternating between kinetic flurries and hushed stillness. Images of young men tumbling towards the bottom of the creek are followed by images of them climbing back to the top, bracing themselves once again for the fall. Through these repeated sequences, the act of their diving acquires a ritualistic significance; purge, rebirth, and purge again. Their reappearance on top of the falls is something akin to a resurrection. It also begs the question: what exactly lies at the bottom of the creek? After all, these young men throw themselves into a water that is unseen, a water that we can only presume as the pale bodies glisten with wet droplets. There is only an engulfing blackness, its mystery heightened by these unfolding cycles. In this void, the past, present and future intertwine. There is no beginning nor end. Suspended against a vast backdrop of infinity, these divers find themselves somewhere between a collective tradition from the past and a more private dreaming of the future.

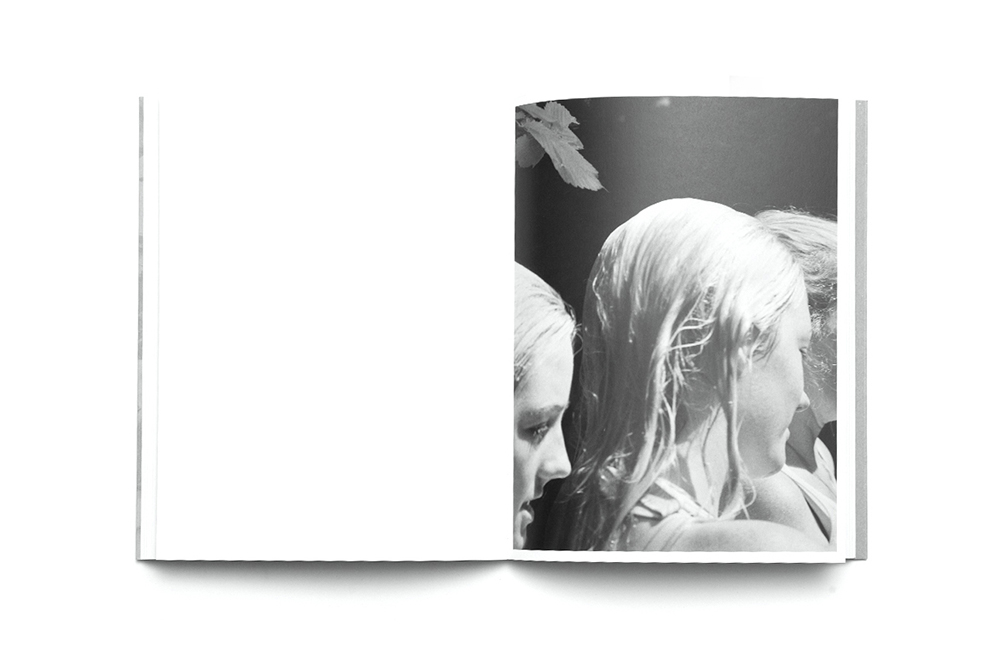

It is a future that is as daunting as it is alluring. Meeks’ subjects are often captured in moments of internal retreat, pausing and pondering before they step over the edge. The falls become a place for self-reflection; these young men are grappling not only with the modern world which they have escaped but also with themselves. In one image, a young man rests on an outcropping, staring pensively into the abyss below as if awaiting some kind of revelation from its darkness. It is also an arena charged with the demands of budding sexualities. With adolescent girls and small boys present, masculinity – performed through competing displays of leaping and lunging – is spectated, and admired, by on-looking eyes.

Yet, while these images exhibit the virility of such flexing and posturing, they are also infused with shyness, sensitivity and inhibition. We find teens retired beneath the shadows of the falls, spectating rather than performing, deliberating rather than diving. With their lean bare backs and stretch-marked skin, these alabaster bodies speak of the same delicacy of the silver butterflies which recur throughout the book. Floating amidst an enveloping darkness, their frailty is a reminder of their mortality in the face of a natural world that is far from benign. Though these young men have wilfully climbed up to the falls, lugging with them their dreams and their fears, once they step over the edge, their plummeting bodies are powerless by the hands of gravity, their lives governed by the hands of fate.

This book oscillates between the collective experience of these young men and their private meditations on a future that is yet to present itself. It is, itself, a journey, a rite of passage marking the death of one phase and the birth of another – just like the butterflies, now at the end of their lifecycle. There are no conclusions in Halfstory Halflife, only transitions. “How did we get here?” “Where are we going?” So ends Meeks’ book, with a young man sat on the cliff-edge, poised for the dive yet overcome with uncertainty. We do not know what happens next, but what we do know is that he is perched at a precipice both in space and in time.