Studio Visit: Stefan Ruiz

Brooklyn-based photographer Stefan Ruiz describes himself as a collector. He collects bicycles, paintings, and records. He also collects people; he’s traveled around the world in search of stories left untold. Although his sharp insight and vivid aesthetic lends itself beautifully to editorial and entertainment work, having garnered awards and appeared in leading publications like the New York Times Magazine, L’Uomo Vogue, TIME, and Rolling Stone, Ruiz’s personal work is decidedly about the eccentricities, nuances, or as he might put it, the “weirdness” of the human race.

Prior to moving to New York City, Ruiz served at the Creative Director for Colors magazine out of Italy. Ruiz’s first book, People, features a selection of portraits from around the globe, their subjects ranging from the residents of mental institutions in Cuba, to the prisoners whom he taught painting at San Quentin State Prison. In 2012, Aperture released his fourth book, The Factory of Dreams, for which Ruiz documented the nuances of the Mexican soap opera. One of his recent projects centers around the Cholombianos, a subset of youths in Monterrrey, Mexico, who style themselves according to a distinct amalgamation of influences from the Colombian coast.

I visited Ruiz in his home and studio on a lush tree-lined street in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. My cab driver, who came with me from suburban Westchester, instantly commented on the hipness of the neighbourhood; it’s a place for artists, and it’s a place for young families. Ruiz, despite his busy schedule, is surprisingly soft spoken. Our conversation was punctuated at times with small pauses, and he was comfortable with silence and taking time to think; he’s not someone who wastes words on small talk.

How long have you been here, in this studio?

Oh, a long time. I bought it like twelve years. I kind of live and work here, except I travel a lot.

Why did you choose to live in the studio? Why was it important to have the two worlds together?

It’s not. It’s kind of I think a necessity. There are two apartments above I rent out. I moved my bedroom here because it’s quiet, and so I did that, but it’s kind of weird because now everything is mixed.

Is it hard to separate work from your life?

Yeah, because there’s always something to fix.

What does your typical day look like? Do you have one?

If I’m here, I get up and obviously check my emails. A lot of times I’ll have emails coming in from Europe overnight, so I’ll deal with those first and then normally Patrick [Stefan’s assistant] comes mid to late morning, and then we will start going through whatever needs to be prepped – whether it’s book stuff, or magazine shoots. I shoot film a lot (I shoot digital too), so we’ll do the scanning and the contacts and the negatives.

You’re a bit of a collector. What are your favourite things in your studio?

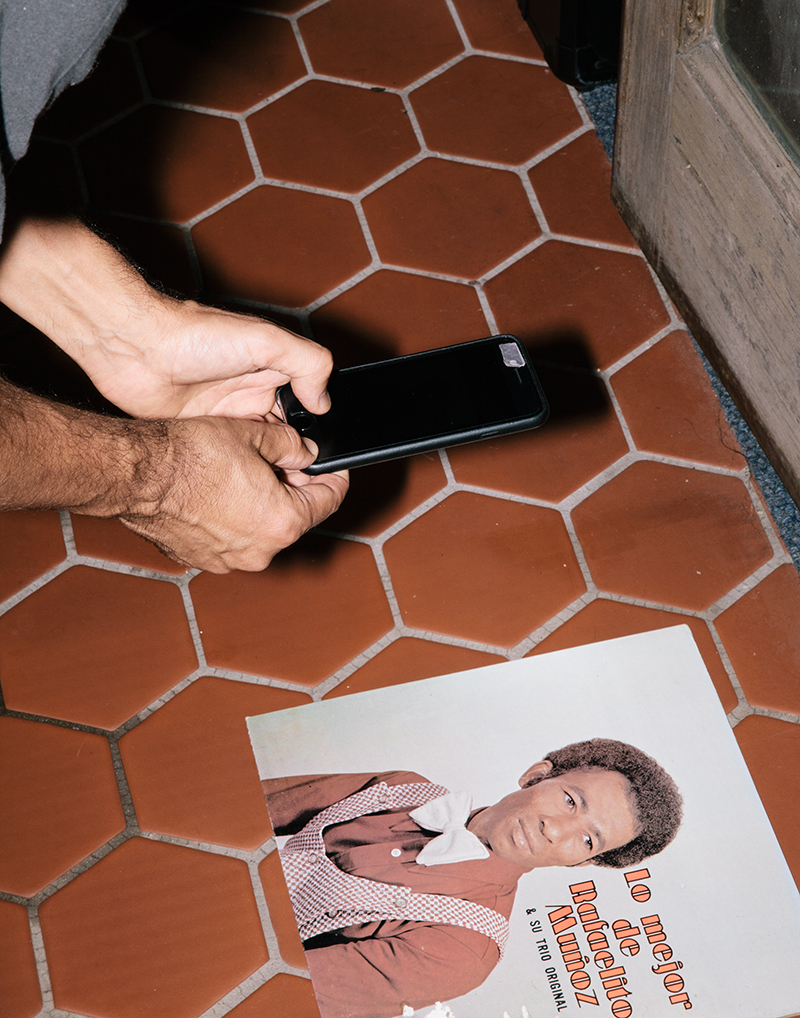

I’ve been traveling a lot so I’ve bought a ton of records. I’ve got like four turntables; I DJ for fun. I was just in Cuba, so bought maybe 200 records. Before that, I was in Columbia. All these need to be cleaned. I’ve run out of space now.

I like photo-based things. I like these photo-portraits; I found them in Mexico. They do a black and white photo and then they colour them. The problem is they’re really fragile. Some people try to clean them, and then they get ruined; I should put glass over these. I try to buy some photographs; this is a Malick Sidibé, he’s a Malian portrait photographer. This is an old one, a vintage print.

I like random things I find. This I got in South Africa – it’s a boy’s initiation mask. I like either weird photo-based stuff or wood things. I’m not religious at all, but I like religious imagery. I like bikes and I collect bikes too. Weird wax things from Brazil, prison art. I’ve got little Pablo Escobar [figures]., some books; I’m not buying as many books because I’m trying to make my own.

Could I see the Telenovela book? What inspired you to make this one?

I guess the thing about it was I think the world’s kind of obsessed with fame. I wanted to do something that was kind of a documentary project but of something I didn’t really like, in a sense. I think a lot of people do documentary projects on things that interest them and that’s cool, that’s normal, but it was a challenge to choose something that wasn’t necessarily my aesthetic.

I was also interested in the fact that some of these people are super famous; you wouldn’t know them but if you go to parts of Russia or Eastern Europe and other parts of Latin America, or even France or Italy, they’ll show these. It was kind of this weird thing about fame.

The other thing about it is that they’re selling these fake dreams to people who basically can’t live that anyhow. The average person who watches that is probably poorer; they’re never going to have that kind of lifestyle.

How did it first come about?

I started doing it with Colors and we did a whole issue on it. It was really hard at first because I was trying to not necessarily make fun of them. I wanted to do something where if you liked them, you’d like the work and if you didn’t like them, you would like the work.

It’s too easy to kind of make fun of people, especially with a camera, especially with a subject like this. So yeah, some of the photos are funny, but 90-something percent of the photos in there are polaroids as well. I would show the subjects; we would look at them, and they’d say ‘oh, okay’ or ‘oh, I want to try this.’

Normally it was in between scenes. Mexico is the largest soap-opera maker in the world. There’s a formula to the Mexican soaps; a lot of times it’s people being upwardly mobile. This formula works well in developing countries – it’s aspirational. All those things were interesting to me.

How did you avoid slipping into going the easy route and making fun of your subjects?

Normally, they’d make between three to five soap operas at a time, but in different studios. It’s a big lot in Mexico City. It’s Televisa; there are lots of things going on at the same time. They would let me pop into the different studios, maybe for a day or part of a day. You can’t do anything while they’re filming, but as they got to know me, I’d set up my camera. I would use their lights and as soon as they were done filming, I’d get whomever I could and have them come over for a portrait. They’re in their clothes and on the set of the soap opera, but they’re somewhere in between themselves and their character. I was interested in this weird reality and fantasy [dichotomy]. It’s a weird book; people either really love it or they just don’t get it, and that’s fine. It [soap opera culture] is like culturally looked down upon.

Has working on this project influenced the way you photograph other celebrities and think about fame?

Ah, well, maybe a little bit. I do shoot a fair amount of celebrities. I always try to make them look alright, but I also want it to be an interesting photo, not just a glamour shot and something that’s generic. I don’t retouch that much. I’m probably pretty awkward anyway so when I go in, I don’t talk that much. I’m maybe a little better now. The interesting thing is you need that person’s participation. Has it influenced [my celebrity work]? Yes and no. I don’t know.

How much time would you say you spend traveling versus working from home?

It comes in waves. Right now, I’m trying to be here a little more. I’m also trying to finish two books. One is a book of a collection of photos I have, but they’re not my photos. They’re kind of Mexican crime photos; there’s some mug shots, crime scenes. It’ll be like a smallish book.

I’ve been trying to finish the book of the portraits I did in Mexico of the Cholombianos. Just not so many, but do it nice.

How did you learn about the Cholombianos?

Through a friend and then basically VICE asked if they could do this documentary on me. So we did that, and I went back again on my own. The second time I went, it was really crazy dangerous. Now I think it’s mellowed out, but they [the Chomobianos] don’t really exist anymore because the police were cutting their hair.

Why would they do that?

They were associating them with the drug culture or the cartel guys or whatever. They come from really poor neighbourhoods and they listen to this weird music. There were some hardcore people around in the peripheries, at the clubs, etc. We set up a studio outside of the clubs and there were guys in subarus with tinted windows. You couldn’t see anything and they’re just watching you. Once it got really late, the energy would start shifting.

If they caught the Cholombianos, the police would cut or force them to cut their hair. They were totally harassing the kids. The second time I went it was already starting, but I was able to get a handful of images.

What do you think draws them to this culture, despite the fact that the police don’t like it?

What drew them to this is the music. They were all into Cumbia; I don’t know if you know Cumbia, but it’s originally from Colombia and a mixture of African drumming, Spanish melodies and native, indigenous flutes. It comes from the coast of Colombia and it’s really traditional. In the late 1960s, it spread like crazy throughout Latin America.

In Mexico, there were some guys going back and forth between Mexico and Colombia and it started getting really popular in Monterrrey. DJs started playing it and the story was that one DJ was playing it,and the motor started slowing down, and so he thought ‘oh no.’ The tape was playing really slow and people started making all this noise and he turned it off. They got upset! They were liking it really slow so he started playing it.

A lot of these guys now they would play this old Cumbia from like the 1960s and slow it down, talk over it… and they dance in a circle, and they all dance together; it’s like this slow dancing. It seemed like a pretty mellow thing compared to other music cultures. Some of them were really funny.

Does the political climate surrounding that subculture inform your photos at all, or do you want to keep them separate?

I’ve always been interested in art and politics. They’re all part of how I was raised. My dad was a lawyer; he was very liberal. He was into politics a lot. My mom was an art professor and painter, so she was really into art. So almost through osmosis, you know, you pick up the two things.

My father grew up in California, but his family was Mexican. I guess a lot of this stuff has just been my figuring out where he came from. Also, I just like going to Mexico and there’s weird things going on there. I think that’s honestly just part of that. My dad always really wanted to kind of fit in. He was proud of who he was. Now, he lives in Mexico.

I just think with my mom, she’s always up on art. She comes to visit me here and she has friends who are artists and she’ll go to galleries. She has an opinion and she reads a lot. I think I would have stayed doing my painting and drawing but I made some money doing photography and I was able to travel doing it. Painting and drawing, you just sit in a studio by yourself all the time.

Do you still paint?

A little bit, I’m trying to do it now. This summer I’m going to make [a back room] into a little studio for drawing and maybe painting. I can imagine drawing portraits; I can’t really imagine doing a landscape right now, although I like taking landscape photos. But I like taking kind of weird landscape photos. It’s great to take a beautiful landscape, but I’m not really going to put a beautiful landscape in a book because it’s kind of too easy or something.

You mentioned that you don’t pay people for portraits. Why is this important for you?

If it were an ad job or something, of course it should be paid, but if it’s a documentary thing I think it’s a little weird. People do perform for you anyway in front of the camera but I think it changes the dynamic. I’ve definitely bought people lunch or whatever. I’m definitely fairly generous, but I would rather they’re doing it also because they want to do it and maybe somehow it’s mutually beneficial.

I have shot in refugee camps and that always feels a little weird to me. I’ve never paid any money in a refugee camp. In a refugee camp, everyone’s a refugee. They’re living somewhere else; they’ve left everything. There’s a war going on wherever they’re from. It’s ethically ambiguous. You can be trying to help the situation, but a lot of times, I think people just take.

How do you deal with that?

I don’t know. There was this guy who came up to me the first day I was in the refugee camp [in Tanzania], and he asked me to take his picture as soon as I got out of a car. I wasn’t really set up, but I said okay. As I got my camera set up, his friend pulled up his sleeves and I realised he didn’t have any hands.

I probably would have felt really bad asking the guy to take his picture if I knew he didn’t have hands, but he had asked me. He said the reason was he wanted people to know what had been done to him. They were refugees from Burundi and Rwanda.

What would you tell your former self about making a book?

I think in some ways you have to keep things simple. I tend to complicate things; I want to include everything. I would like my books to make some kind of statement, but maybe not hit you over the head with it. A project that makes you think; raise some questions. I think humour is valid.

Will ‘people’ remain your constant subject?

I don’t think I would make a purely landscape book. It would probably have to be a statement about what people are doing in the landscape. Yeah, so I think it’s kind of about us, the world in general, just humans.