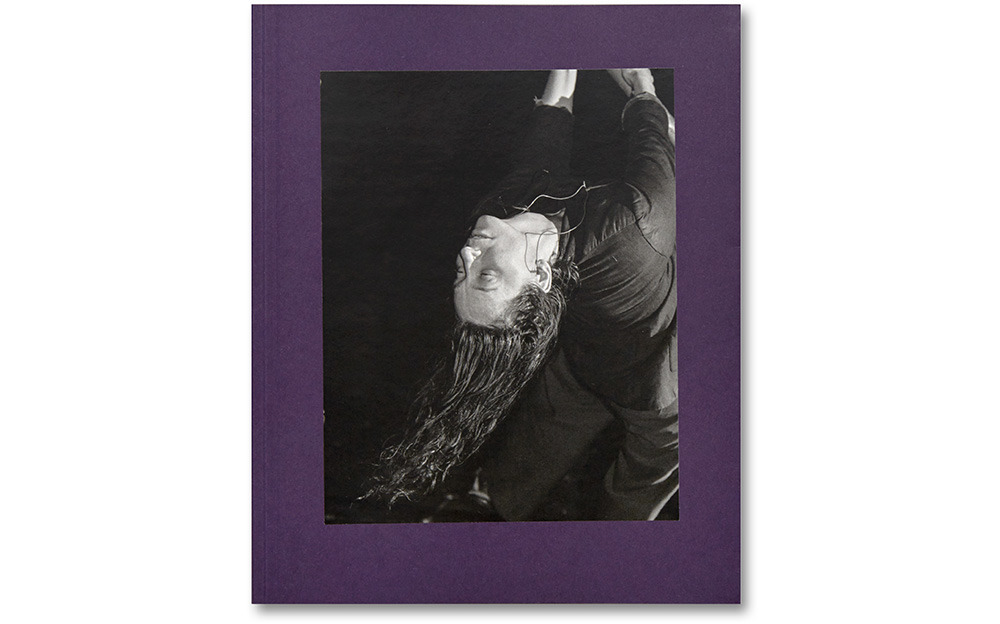

Adam Pape – Dyckman Haze

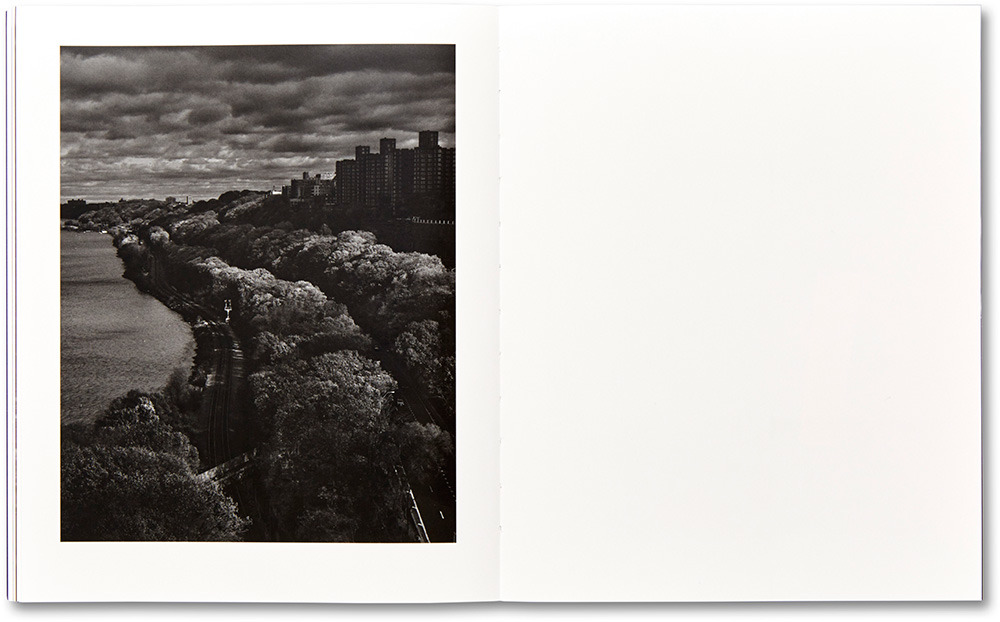

Even the general tendency of American cities to be laid out in grids – compared to their often more organically structured European counterparts – can’t entirely conceal the fact that all urban centres contain a complex multiplicity of different spaces; some overlapping, and some that startle in the rapidity of the juxtapositions they impose. Learning to navigate these different spaces is a key facet of the modern urban experience. Adam Pape’s Dyckman Haze (MACK, 2018) is a study of various New York parklands, places that would seem to be the exceptions to those qualities that define the city itself; natural against man-made, horizontal against vertical; and although precisely delimited in themselves, by being unbound from the constraining grid, the experiential boundaries within them tend to become blurred as well. It is largely because of this that these spaces seem set apart from the ordinary flow of city life, and Pape is careful to depict them as such, framing the book with distant views that show the parks butting up against the jagged margins of the city proper.

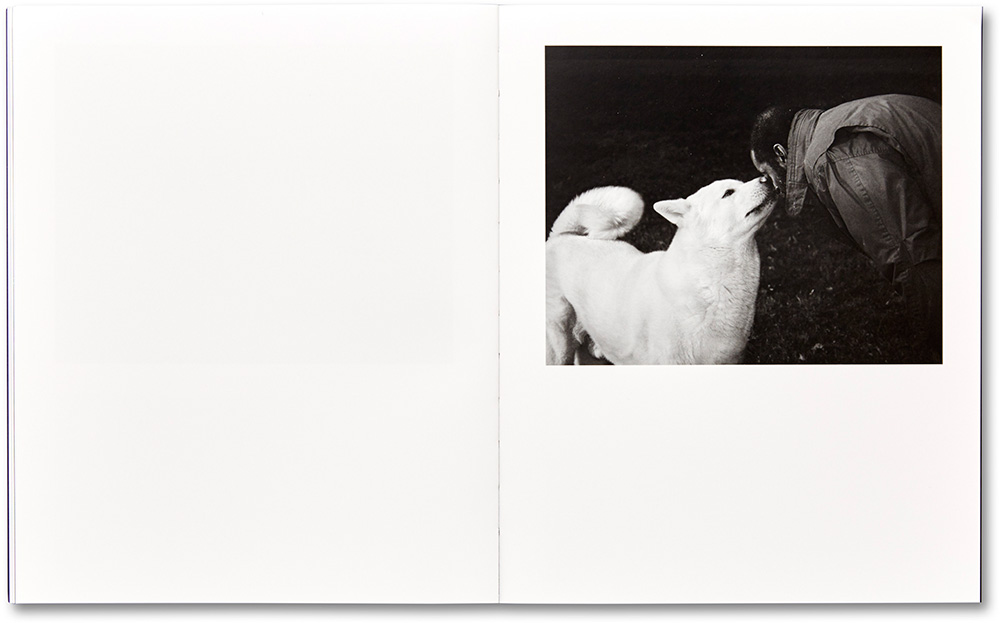

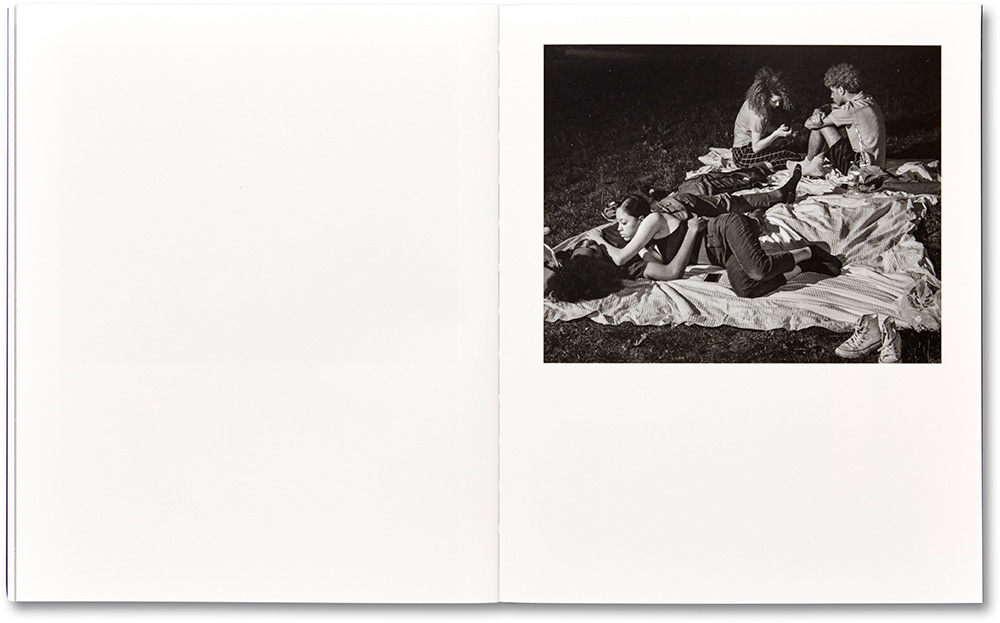

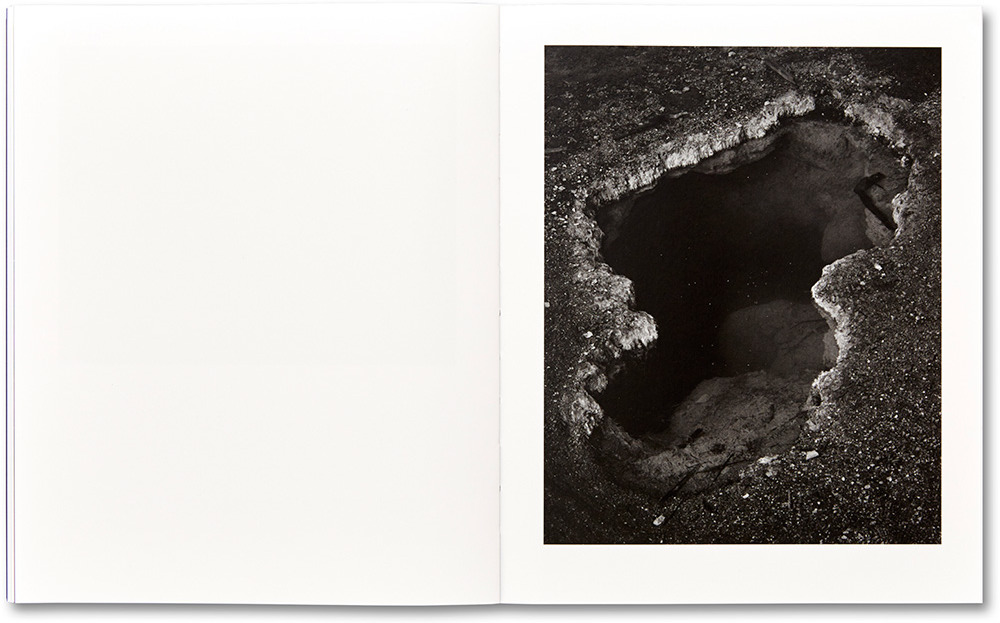

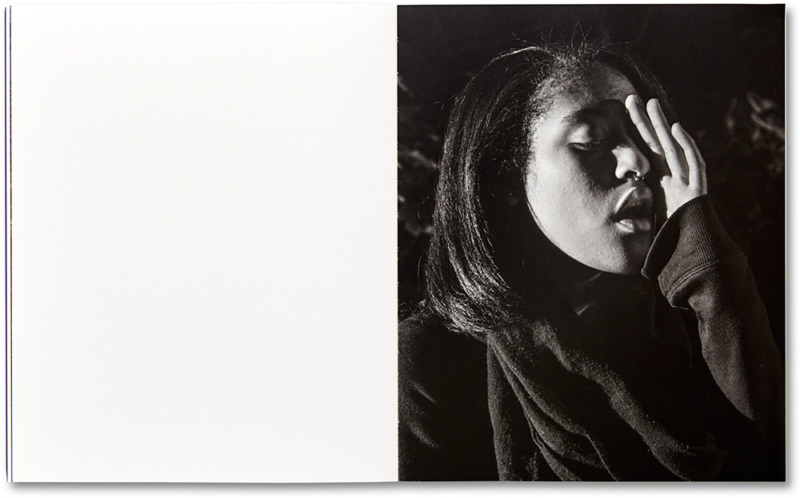

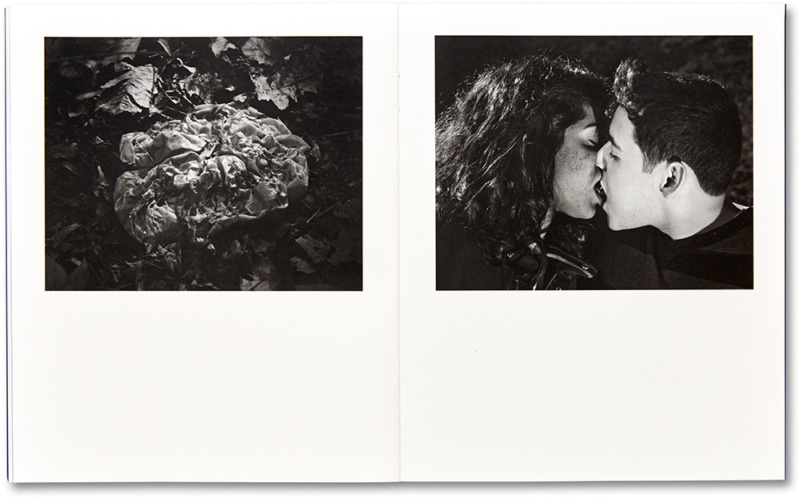

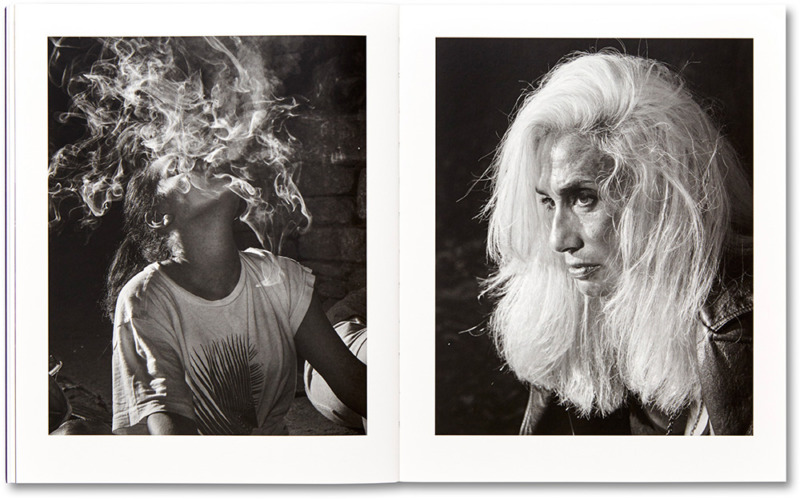

Gradually we abandon the buildings and streets to become fully absorbed into the perpetual twilight that defines these images. In Pape’s view, the parks are the ‘unconscious’ of the city, a realm of urges and roles that can’t be followed or enacted in daylight on the streets, even in liberal New York. The deliberate decision to suspend time in the work – it’s all just ‘night’ here – feeds into the recognition that the parks are a place apart, with distinct rules, just as the unconscious itself can’t recognise distinctions between fantasy and reality, knowing no limit but the immediacy of its need.

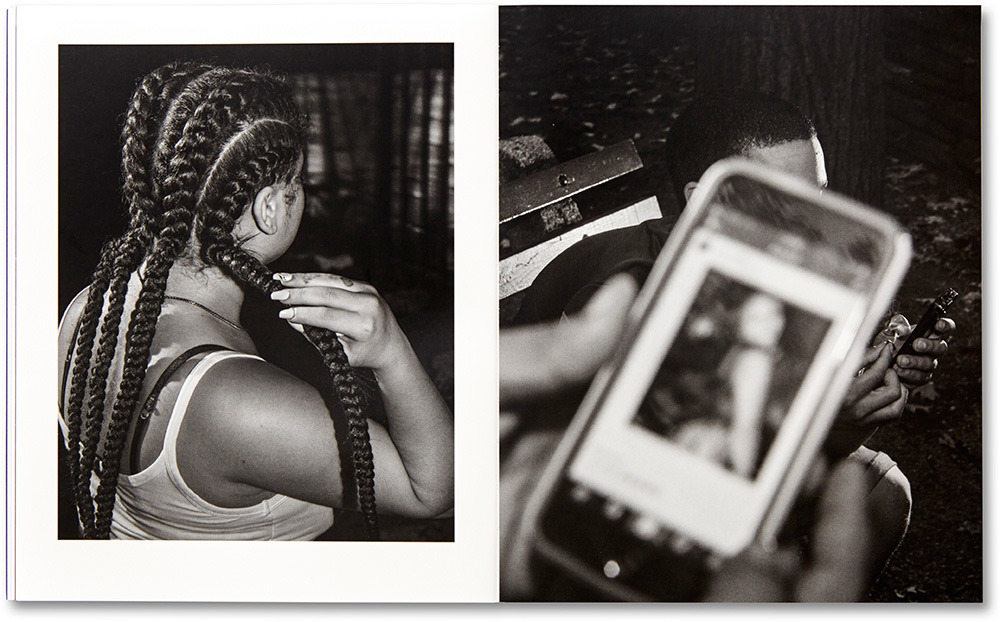

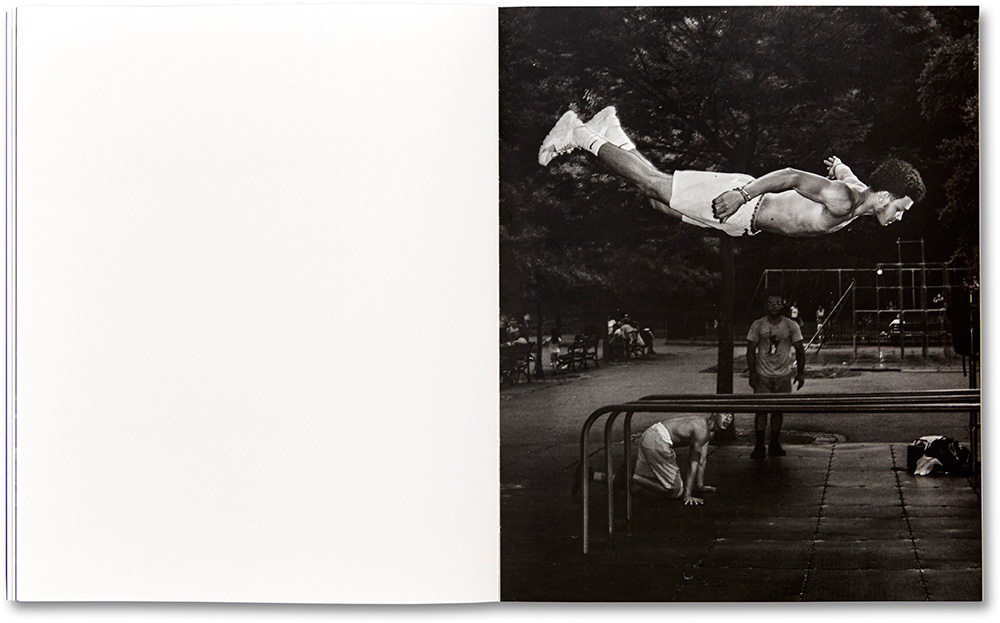

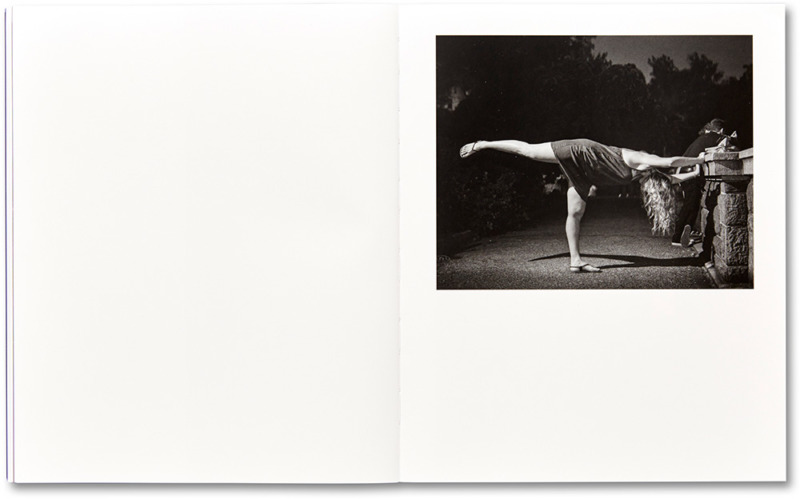

The apparent theatricality of his images emphasises this point; artificially lit and embracing situations that seem to have been at least partially staged for the camera. The images can still be ‘true’ without the stylistic trappings of documentary veracity; this is about describing states of mind and ways of experiencing urban space that doesn’t lend themselves to a more direct approach, so Pape’s images span the metaphorical and the descriptive, without feeling obliged to privilege either. They, nonetheless, retain a tangible social relevance, insofar as we are seeing the reverse side, the underpinnings, of a precisely stratified city, as well as showing how a marginal space attracts those people who can’t always claim – or sometimes simply don’t want – the fixed roles that a less fluid territory would require them to inhabit.

Of course, the ‘nature’ of New York’s parkland, like that of most cities, is a carefully constructed illusion; there is nothing properly wild about the growth of these places, at least in their conception. But that indeterminacy, the confusing interface between the natural and the man-made, is of significance because of how it allows Pape’s cast of characters to ‘act out’ in the park spaces. At the same time, he refrains from showing us any actual violence or the darker shadings that these landscapes no doubt contain, perhaps fearing such content would tip the work more fully into a social documentary role. The figures in his pictures retain their interiority, receding into their imagination; just as the parks are a recessive space in the city, a relationship shown by the repeated views of seemingly distant buildings framed by the trees that make up the parks, so that the city itself and the everyday world that it represents start to fall away.

The many images of people smoking also

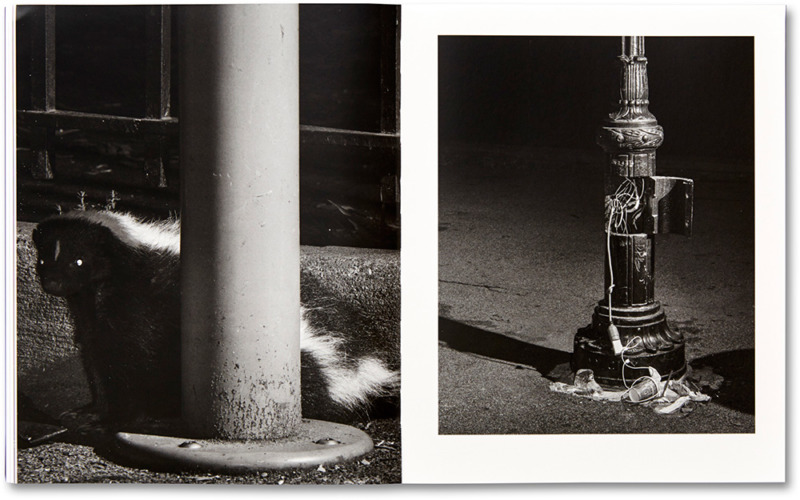

In that respect at least, the parks take on the qualities of the city that encloses them; this is because we tend to invest or project our values onto all the spaces we inhabit. So, although they seem to be places set apart, to enter the parks is to experience the complexities of the city in miniature. Pape’s physically and psychologically immersive tour of these park landscapes is ‘about’ the specific places it depicts, then, but he also recognises them as sites where the veneer of the city’s apparent regularities has been stripped away. They are in this respect ‘pure’ spaces, that can, regardless of their more planned aspects, potentially return their visitors and inhabitants to an experience of a landscape that is almost premodern, even primitive. This regressive quality is in some cases shown directly, such as with the wires spilling out of a broken lamp post – civilisation becoming unravelled – but is more to do with the mood of Pape’s subjects, who drop their social masks, or pick up new ones, which they perhaps couldn’t wear in their work-a-day lives.

This state of absorption, almost ritualistic in nature, can also be seen in the faces and in the attitudes of those who are ostensibly using the park as a place to exercise, but who in the pictures, take on the look of a celebrant in some kind of ecstatic rite. And although you might return to yourself after such a journey, you couldn’t help but be changed; Pape’s night-time excursions are surely much the same.

All images Adam Pape, Dyckman Haze, spreads courtesy MACK, 2018