Control

The primary practice of an artist is control. The notion and ownership of control has never been as fluid as it is today. Editors, curators, publishers and artists are all demanding a differing stake in which part of the process they own, and the boundaries between these roles are being redrawn. The recent rise of self-publishing is testimony to this. Artists have taken back control of where their work can be seen and how it is appreciated. In a similar ascension, independent publishing houses are jostling established trade publishers in an effort to reclaim the market. Some might say that this is oversaturation: a broth with too much body that masks the notes of an otherwise delicate composition. But it certainly doesn’t feel like that – it feels like now is an exciting moment to create, edit, or consume visual arts books.

At Magnum Photos’ annual general meeting this year, a seminar was held discussing photography books, their artists, editors and publishers. Susan Meiselas – whose book In History won the 2009 Recontres d’Arles Historical Book award – succinctly noted that the culture of bookmaking comes from a different culture to where the work originates. This is because books are inherently ‘made in time’: the artwork is made in a period of time; some time passes; the book is made in a separate moment, of its own motive beyond the work. In this final slice of time, there is undoubtedly some reflection and development which inform – and in some cases largely dictate – the narrative, or narratives, of the book. And of course, the current technology can play a pivotal role on the form of the book: the second edition of Meiselas’ 1976 Carnival Strippers that was published in 2003 contained a compact disc of original sound collages, made when she was travelling New England’s fairs and carnivals to capture her subjects – something that could not have been done twenty-seven years earlier. Thus, photography books are not just a complimentary product but a work in their own right.

Without a doubt, the history of photography as a medium has influenced the art of the photo book. For an art form which relies heavily on tangibility and the physicality of the piece, the shift from film to digital, gallery to online has reinforced the value of the book as an object and more than a mere catalogue. During his own talk, David Alan Harvey stressed that a photo book is a mark of prestige for a photographer, and a considerable milestone in their career. In previous years, the mark of a serious artist was evident in their exhibitions and their online activity, but once more publications are paramount. Could we soon see the second ‘golden age’ of photography?

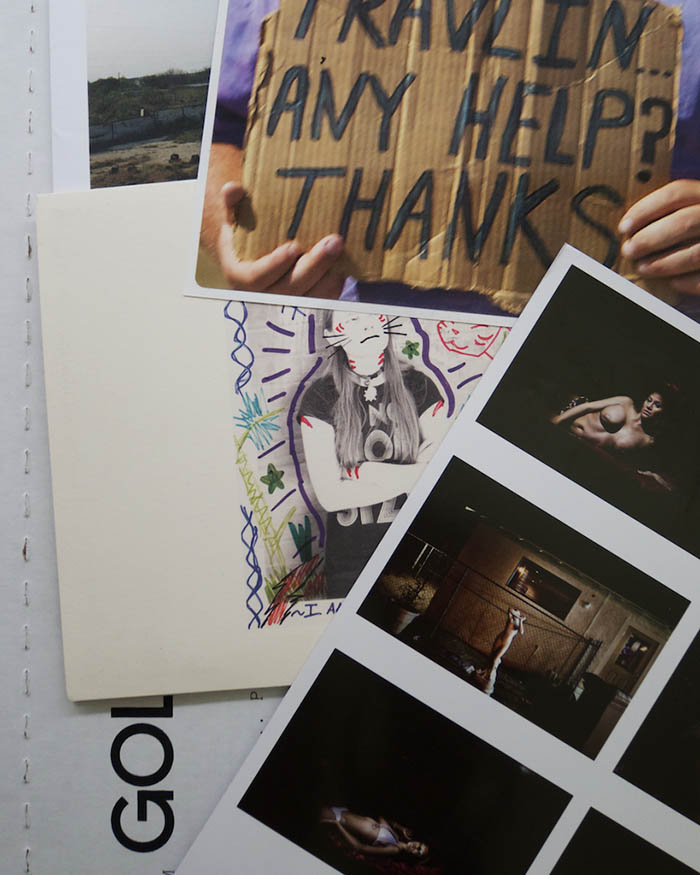

Two years ago, Meiselas teamed up with fellow Magnum photographers – Paolo Pellegrin, Jim Goldberg, Alec Soth & Mikhael Subotzky – and writer Ginger Strand to explore independent and collaborative efforts in art practice. Setting off in an RV from Austin, Texas, they spent two weeks and almost two thousand miles making work, and coming together to observe the result. They noticed the common themes running throughout each individual’s work, and started assembling material that collectively documented the experience. What came out (titled Postcards from America) was a collection of objects rather than a book – a box of books, stickers, zines, fold-outs, cards, newspapers and posters – that exist as an assiette of the experience. Each narrative transmuted its essence into a form that best represented how the story should be told. They had taken control, at every level.

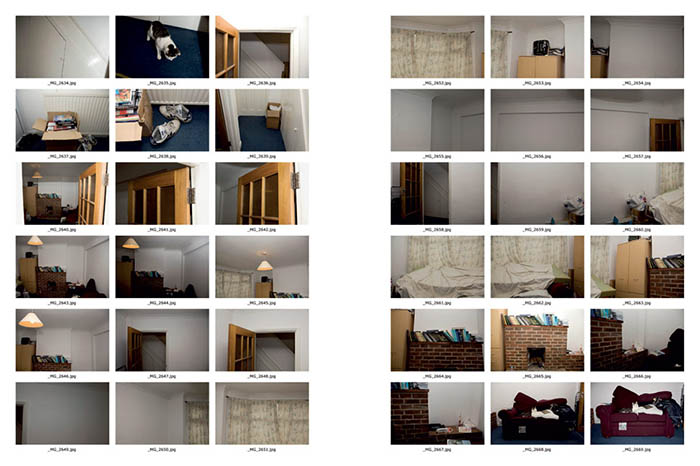

Harry Hardie of Here Press expanded on those ideas. In his view, independent publishing is akin to making a concept album rather than a greatest hits record. Although the content of a book can work within an exhibition or online space – each photograph or spread representing a certain track on an album – a book is ‘a new manifestation of a view of the work’. The concept of a book is similar to a consommé, in that it must be rich and concentrated, but also clear and easy to palate. Control Order House by Edmund Clark, published by Here Press, was borne out of this idea and the concept strongly governed the publication – in fact, it was an almost completely different work to the original. With unprecedented access to a Control Order house (a state-owned property where people suspected of involvement with terrorist-related activity can be detained) and its occupant, Clark set about documenting the house for nothing more than personal reference. He made sketches of the interior, took photographs of each corner and wall of every room, and the few items of furniture that the suspect – known only as ‘CE’ – was allowed. The pictures were never intended for public consumption and would only illustrate an online virtual tour of the house, if ever used. But when coupled with the various notes made by Clark and the cloying writs of the Terrorist Prevention and Investigation Measures surrounding CE’s incarceration, a new narrative was forming. The imposition of the state on an individual was ever more clear, and claustrophobically so, a sensation usually better suited to other, more visceral artistic disciplines such as film or interactive theatre. With such a weighty concept reined in and controlled, Hardie was able to publish the book as he felt the story should be told – and the effect was more subtly seeded. This type of publication is far from the book as merely a collection of well-produced prints.

However, no matter the quality of reprographics, the guise under which a picture is presented can have an incredible impact on its dynamic. Referencing their upcoming book Spill by Daniel Beltrá, Gordon MacDonald & Stuart Smith of GOST Books pointed out that a photograph of an oil spill, though beautiful, may be received differently in a magazine compared to a book. Certainly the audience is subject to a set menu when reading a magazine, the articles providing the propulsion and pictures left to adorn the page; and so text in a photo book must be dealt with carefully. In photo books with pictures and text, people have a tendency to veer towards the text and consider the pictures as illustrative. It’s necessary to pull and push the elements of a book’s design until the desired effect is achieved, and it’s quite a struggle. An improperly formatted contextual note may come across as the title of a piece; essays that follow the main body can feel like footnotes; a leading epigraph can deliver the body prematurely and spoil the revelation of a narrative arc. As a result of this, one can also move in and out of roles, from editor to designer to audience, and once again the action of control plays a heavy part.

It’s clear that as has happened in trade publishing, with the role of editor and publisher merging in the 1970s, the boundary defining one’s function as an editor, photographer, or designer is becoming less of an obstacle or distinguished purpose when working on publishing projects – and the title of ‘publisher’ is being reclaimed and redefined. Whatever one’s role, we were once limited by what could be done with a project – what technology would allow, and what people would buy – but now it’s not necessarily so, and the interchange and exchange of material is so frenetic that we rarely notice where – or who – things come from.

In the act of authoring, the artist holds authority and control over pieces of the whole. Editors and curators control what they put forth and where it is put, refining the artist’s practise and helping a piece to become more than the sum of its parts. The audience controls what it sees, but not necessarily what it feels. Therefore, if a project is to stir a feeling from the audience, the stakeholders of a project – artists, editors, curators and publishers alike – must control deftly what the audience sees.

A book is not simply a composite of arranged elements: it is the result of controlled creativity and the exertion of authority.