Hayahisa Tomiyasu – TTP

All images © Hayahisa Tomiyasu, and spreads © MACK, 2018

Coincidence makes a good photo. In literal terms light and surface must coincide, if these don’t meet perfectly then the image will be blurry, underexposed, or not exist. But more than that, the most memorable photographs are those where the photographer is coincidentally in the same place at the same time as the person, the place, the event. The mythology of the camera is that of capturing coincidences—some photographers may even go as far as to fake the coincidence to make a better picture—the suggestion of chance makes a better story, the unexpected and surreal coincidences are those that are best remembered, and best told.

Hayahisa Tomiyasu writes in TTP, winner of the MACK First Book Award 2018, of a series of coincidences that occurred in 2011 in the city of Leipzig, Germany, where he currently lives. On the morning of the 14th of August, 2011, Tomiyasu was walking around his neighbourhood when he happened to cross paths with a fox defecating on a grass verge. Two weeks later, on the morning of the 30th of August he looked out of his apartment window and caught sight of a fox running across the athletic grounds opposite; the fox stopped briefly at an outdoor table tennis table before disappearing. Tomiyasu waited again for the fox, but in time his photographic eye turned to the table itself.

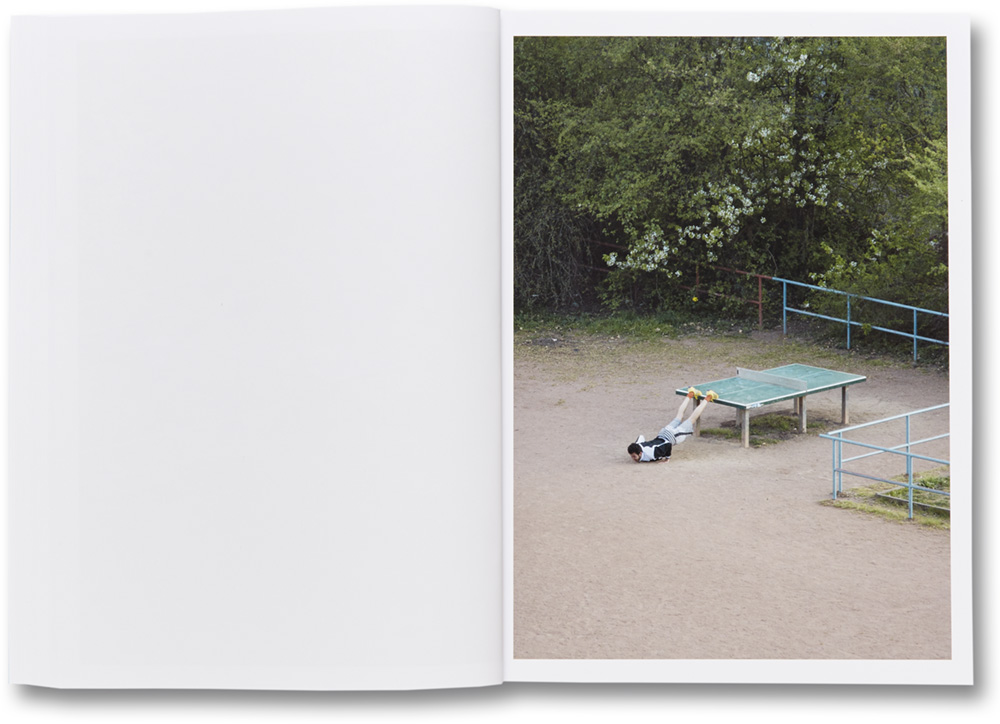

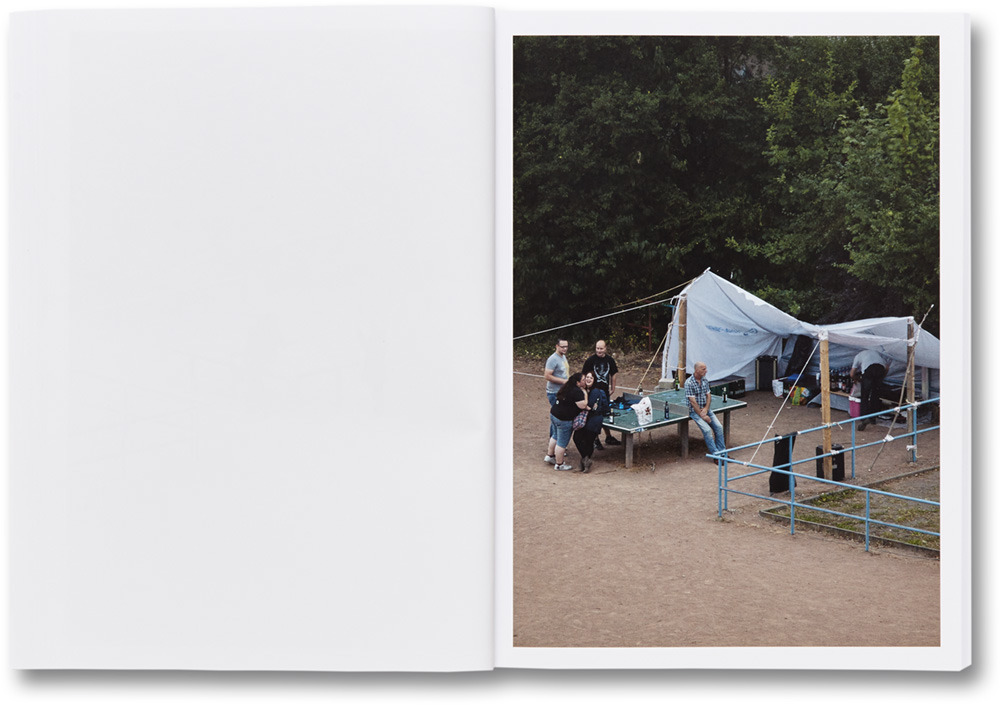

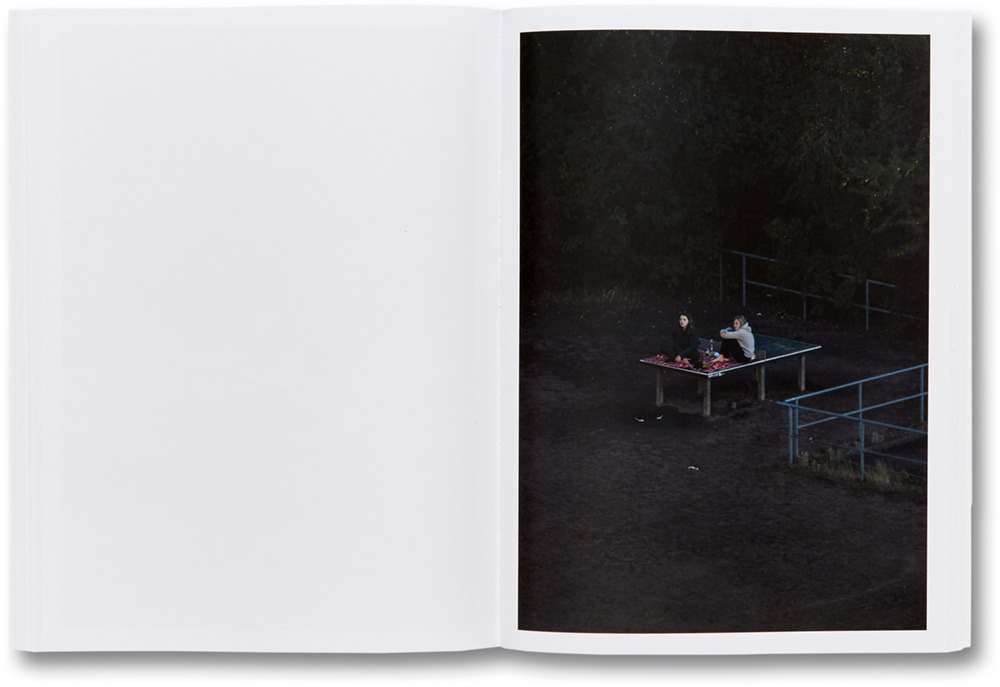

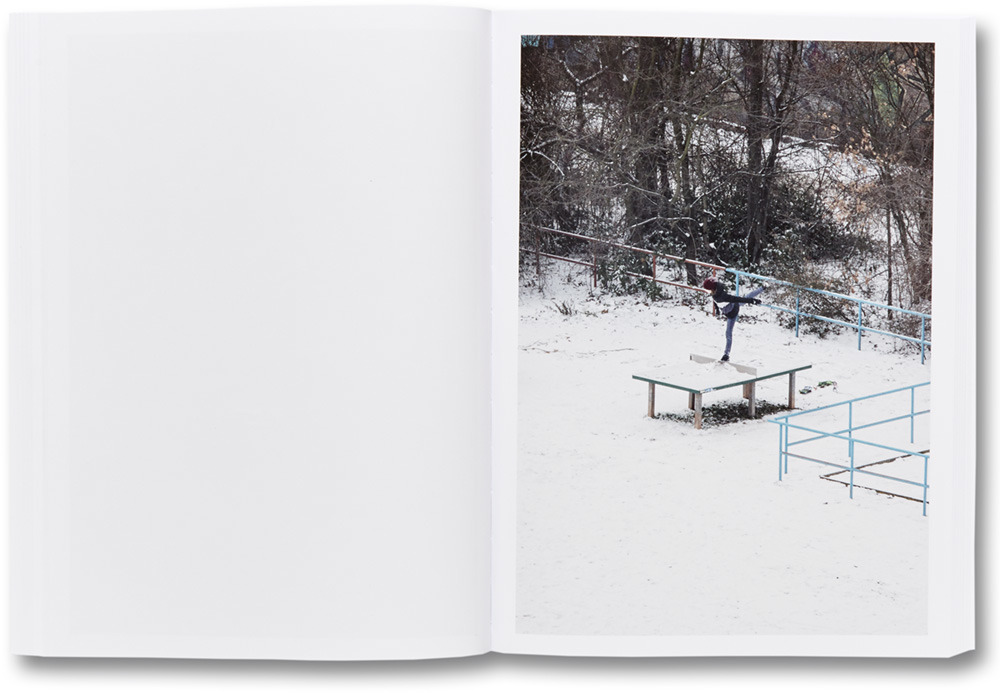

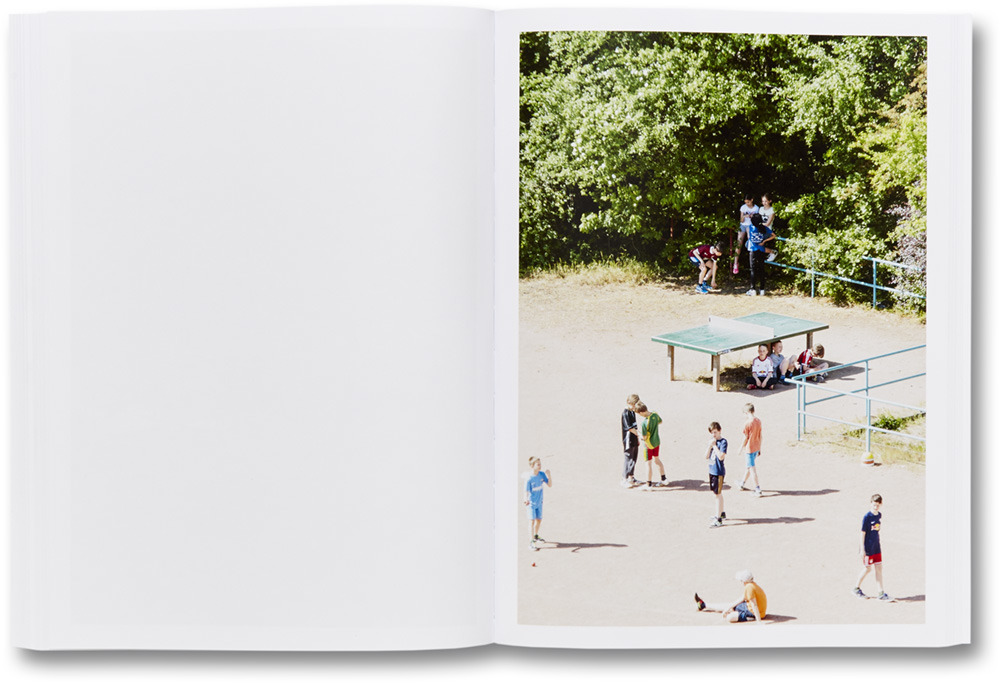

TTP pictures the table, the Tischtennisplatte, and the people who use it over an indeterminate time. Each photo resembles the others, each occupies a single page, oriented portrait, angled downwards from the eighth-floor window of Tomiyasu’s student residence, cropped to show a gravel path, a blue metal fence, the overgrown foliage, and the table tennis table. Over the pages, people in sports gear use the table as a bench to stretch on, others prop their bikes against it, and lay it with bottled drinks and snacks. A child aims a bow and arrow, shirtless boxers fight, teenagers rollerblade, young women practice yoga, some dance on it, and some people simply sit on it. Nobody appears to be aware of the camera, if they are then they’re untroubled by the voyeur. The only thing they don’t do is play table tennis.

Between these pictures, it’s difficult to place the table in time and space. The pictures aren’t ordered chronologically or by people or activity, but there is a rhythm to them, that appears in the small references between pictures; short series that play off one another. Time passes too, but this is marked only by the randomly changing seasons and light of day; slightly longer shadows, browner and fewer leaves on the trees, melting snow, puddles that appear and evaporate. The table is a strange place—there are no pictures outside of the frame, no sequences or continuity, just person after person, table after table. The restricted view of Tomiyasu’s lens and the variety of people and their generic European fashion makes it difficult, if not impossible, to know exactly where the table is. The table is a secluded world, one that attracts but doesn’t hold people. What has drawn these isolated groups here, was it the photographer himself? There’s a tendency to read this large body of work as definitive, but these pictures have been selected from an even wider body; what is the message in Tomiyasu’s selection of pictures?

Then the table moves. It’s only slight, a couple of metres, but it’s noticeable. I turn back a few pages, trying to see if I missed anything, like the fox that Tomiyasu sought. I keep my eyes open and watch as between three pages the table jumps then returns to its original spot. With nobody in the pictures, it’s easy to imagine the table has moved itself. It’s unnerving. A few pages later the table shifts again, and it’s apparent that even in the structure of the book there is no such thing as certainty; it’s disconcerting.

The table scenes become more unusual; a man sunbathes on it, someone uses it as a washing board for his laundry, another waits till night to squat naked on the table. On the final two pages, the punchline of Tomiyasu’s long-running joke hits. A man sitting on the table next to a girl points directly to the camera—Tomiyasu becomes the fox, caught out by the people that he once looked on—the next page sees the table tennis table suspended from a digger, either about to be set in place or removed on a waiting lorry.

I take my own photographic journey to the table, searching on Google Maps, curious as to where it now stands. Looking down on the city I find the athletic track on a corner of Tarostrasse, a small road off Strasse des 18. Oktober. Moving down to street level, clicking and dragging, I try to get as close as possible. I see the gravel path, the blue metal fence, and the table, but I also see the photo is dated to 2008. Perhaps the possibility of walking through Leipzig and stumbling across the table has passed. Despite many pretences, there is no certainty that an image reflects reality. With TTP, Tomiyasu shows the repetition, the staging, and the editing that goes into every chance photo, acts which further move the image from the real world and into an idealised or imagined place. The myth of photography is undone, photography is not an act of capturing coincidences, but of creating the belief that such coincidences are possible.