Interview – In Conversation: Alec Soth and Glen Erler

Alec Soth, from Sleeping by the Mississippi

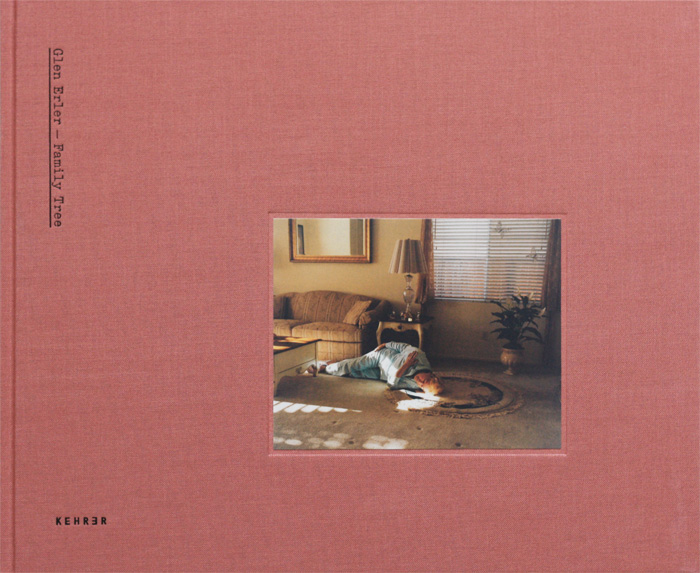

Glen Erler, from Family Tree

Glen Erler (GE): Hi Alec, it’s Glen here. Let me just turn on my video

Alec Soth (AS): There you are, that’s what you look like, huh… okay…

GE: We match beards, I think

AS: (laughs) Yeah, you have quite the head of hair, look at that

GE: It’s a wig actually (laughs)

AS: Is that a trademark?

GE: (laughs) So how are things going, are you in the studio in Minneapolis?

AS: Yeah, that’s right. And you are in London?

GE: Yep, just walked in the door

AS: What are those paintings, behind you? Particularly the one of the woman

GE: My dad painted those; when he passed away a couple of years ago, I brought them back. That particular one is Anne Frank

AS: That’s really interesting about your dad being a painter; that information’s not included in Family Tree

GE: It was just something he did on the side. When you’re involved in the art world and living in London and New York and different places throughout your life, you’re exposed to a lot of different art, so you develop your own taste. So when my dad would paint, he sat in these small places in the middle of nowhere in California and would paint in his spare time. I remember when I was a teenager, I’d be coming home and he’d be painting. Or I’d wake up in the middle of the night and he’d be sitting at his desk and painting. It wasn’t something that I’d look at and think, that’s amazing. I always liked what he did but it was a different type of thing to what I was used to seeing and looking for.

When he died, it was very difficult and it was only then that I really started to look at his paintings. He had a hundred of them, just lying around. When I would visit, he’d take me into a spare room where all of his paintings were kept and would attempt to go through them with me, and me being the kind of typical son, I just didn’t pay that much attention. I’d listen to some of his stories but then my kids would run in and I’d be distracted. So when he passed away, I really had a chance to go through them and I started to feel more for them; he wasn’t accomplished but I started to understand them a bit more. It was an interesting thing to go through, the whole process of his death and dealing with that side of life; you have this hindsight – what things you could done, could have said… I now look at his paintings in a different light.

AS: Since the book seems to be about the retracing of steps, it’s interesting to look at those paintings and try to imagine what he was going through

GE: He had a heavy childhood, with his parents passing away at 13 – and they weren’t great parents to begin with – so this whole lack of love, started to really affect him as he grew older and I think his reality started settling in of what his life was. He then really began hashing it out and dealing with it. So the more time he spent on his own, these things came up. He wrote a little book of poetry that was never published and he wrote a film; he did quite a few things in his spare time

AS: Did he ever visit you in London?

GE: You know what, my immediate family have never been here. I’ve been here almost 19 years; I’ve had 2 nieces and my sister in law that were here for a day, so it’s been one of those things. If they travel they tend to go to exotic places where there’s guaranteed sunshine.

The whole process of Family Tree came about and it seems like you’re the only other person in the world that has been connected to this project, inadvertently, through your curators’ choice award, along with the occasional email correspondence. During that time, I was looking at your work here and there and found it quite interesting; even your earlier projects such as Dog Days, Bogotá and the little bits that I read, it seemed like you were there to adopt a child, am I right?

AS: Yeah, that’s right

GE: In terms of the book, were you photographing while you were waiting, or did the project derive from simply being there?

Alec Soth, from Dog Days, Bogotá

AS: It’s interesting that you would connect with that one, since you made work out of a very personal place. We were in Bogotá for 2 months, our daughter was presented to us and then we were waiting for all the paper work to be done so during that time I was exploring the city, exploring it through the lens during this experience. It was quite unique for me; there’s only 1 picture of her, no pictures of my wife or myself, but it still has that personal story. It’s something I’ve really struggled with, I’ve never been able to do a project that’s directly about my life; I’ve always had to filter it through something else. What about you, would you do an ‘assignment’?

GE: I have found the industry in London to be difficult at times, as an American. It can be quite insular. I didn’t necessarily come to stay here; I came for other reasons. I tend to get projects where they expect a certain thing. I enjoy working with people but I feel the best work comes from being on your own or only with the person you’re photographing. Do you do the same thing; do you take commissions?

AS: Yeah, that’s the thing, I very much work out in the world; but I have incredible admiration for people that can focus inwards, people like Larry Sultan, Doug Dubois, Nicholas Nixon; people that look at their own families and lives, I think the world of that. I do hope to do a project at some point in the place that I live, I can barely photograph Minnesota so I hope to get over that hump. The more you do it, the more you realise what kind of photographer you are. I pretty much have a no celebrity policy because I get nothing from it; they’re photographed all the time and I feel there are so many other people that are better at it. It’s really rare that I do this but on Sunday I photographed someone who I really respect, but it still wasn’t that satisfying. She gets photographed all the time and it was part of this PR machine, you know? She was perfectly nice, but if there’s not that exchange, I don’t know what I’m doing

GE: That’s fair enough, you find interest in other things that you obviously do very well. Unless you have an inner burning desire to change…

AS: In terms of your work, there is this narrative element, this backbone. Like in your book you have these notes in the back, that gives a narrative scaffolding to the project, and I’m always battling with how much of a story to tell and I really respond to people that play with these issues. In your book, the main section with the pictures, it’s very musical, it’s very emotive, and then you get to the notes and it’s the narrative backbone, the tension between these 2 impulses is something that I feel in my own work

Glen Erler, from Family Tree

GE: I always knew there would be notes and text to accompany some of the images; I did go back and forth with it, I didn’t know if I should have it there; it’s sometimes nice for the reader to make up their own mind. Even from a visual point of view, people asked quite a few times why I didn’t have the text with the images and I’ve always felt the pictures need to stand on their own, they need to be by themselves; if someone chooses to read about it, then they can. The images and text need each other; it was always part of the concept, but just not in the same place

A good part of the reason why the book was done was for my own children, they live here, and they were born here… they know that world and feel like they’re American in a way – they call themselves American and their accent is more American than it is British, but they only know that part of the world a few weeks at a time. I felt that it’s an important thing for them to be able to look at something later, to recollect some of the things I went through and that some of the people went through that were close to me. Also, for some of the photographs, they were there with me in the car and me pulling over at the house I used to live in. I’d be taking photos and they’d be around, playing in the orange groves, which is exactly what I did, at their age. I thought it was important that they had these little snippets of this experience and then they can connect with it for the rest of their lives. They’ve met most of their family members who are in the book, they’ve swum in the pools and lived that life so to speak, and so a good part of producing the book was for them

What was the turning point for you, I know Sleeping by the Mississippi was a big project, was your life quite different before that, or have things stayed the same?

Alec Soth, from Sleeping by the Mississippi

AS: I didn’t have an ambition to be a professional photographer and when it came out, everything changed. So it’s like 2 different lives, essentially. Even though I still live here in Minnesota, I’m still married to the same person; there is a kind of breaking point that came before and after

GE: So from that point on, obviously life changed. Were you doing something completely different beforehand?

AS: I’d done different photo jobs – I’d worked at a newspaper, I’d worked in darkrooms and realised that I didn’t really like working in photography in that way. So I ended up working in a museum, in photography, and it was a comfortable existence; low paid but a regular job and I sort of assumed it would be that way for a long time and I would do my work on the side.

Mississippi came out and I sort of had to leave my job, I had to change my life. I then started taking on commissions; it was necessary to sustain things. So it was this process of figuring out how to make a living, which I’m still doing. If I do a certain type of photography for a living, I’ll start hating it. So I do some teaching, some editorial work, I do print sales, and I really just try and keep it fresh for myself. My struggle is to keep listening to that inner voice, to do the thing that I really need to do, rather than do something for the marketplace

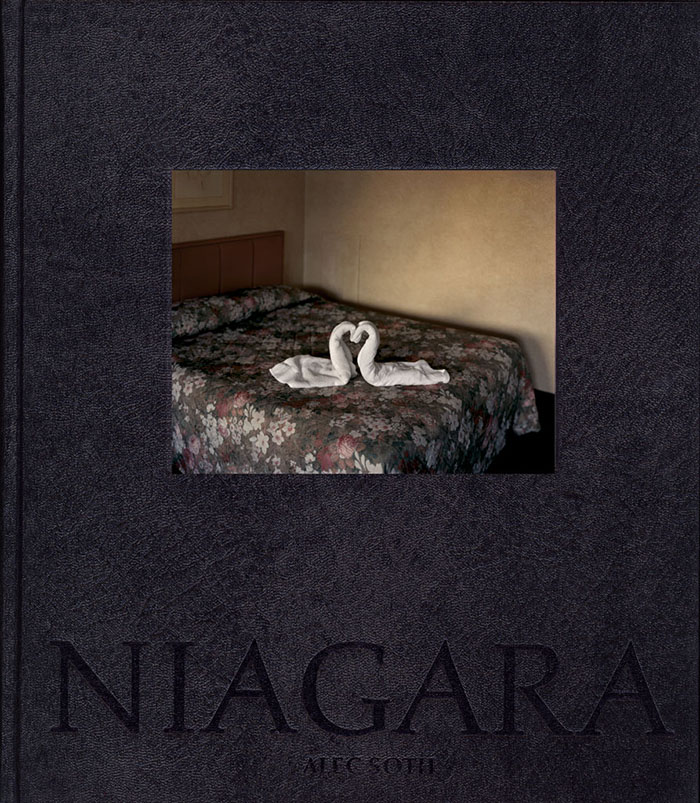

GE: Your pictures may not come from a place like where I’m delving into – my life and my family life, but they still come from a place that means something to you and maybe even to the people around you. One of my favourite projects of yours is NIAGARA. I liked it because I found it darker; I found the printing darker, the book was darker, and me being darker myself, thinking, this is great. Was that a conscious thing? Sleeping by the Mississippi was light; it had a documentarian sense to it

AS: It’s really nice that you say that. Mississippi is always viewed, particularly overseas, like a critique of American culture, and I always think it’s really light and joyous, partly because I felt joyous making that work. Whereas NIAGARA was a much darker time for me, I was exploring darker themes, so I definitely think of it in those terms and I can definitely see the connection with your work. You are, one of the darkest colour printers of all time, it’s like, you push it down there and I totally respond to that My ambition is that each big project is like a film or something, so I can take a different approach based on where I’m at during that time. I actually really want to do something happy someday; things tend to come a lot darker than I expect. But I also want humour and I think that’s in NIAGARA.

GE: Yeah definitely, I think everything’s there. It was also physically darker; I felt the paper stock – not from a technical point of view but I felt that it was more absorbent. I might be mistaken but the cover might be black

AS: Yeah, the cover’s black. It makes me wonder, how did you come to a pink cover?

GE: It was a last minute thing. The cover had a different picture on it; it came from the very beginning, I thought this is the first picture I took, which is the first picture in the book of my aunt holding a photograph of her daughter who died of AIDS. It was put there as a test in the beginning of the design process. I knew that that picture wouldn’t end up on the cover but as it’s a very important part of the story, so it was a good place to start. Towards the end of the design process, actually just before going to print, we started working on the cover. It was just one of the colours that stuck out, and also it’s my mums’ favourite colour to be honest. I used to make fun of her, she still has it around her house, this kind of peachy pink colour. My mother is on the cover, so it made sense

AS: I think it’s a really good colour, I think it’s funny how these decisions are made. In my case with Mississippi, I had pictures on both the right and left pages, right up until several days before we were going to print and then I suddenly changed everything at the last second; the cover decision was quite radical but I was really happy with it. It’s terrifying and exhilarating how these decisions are made. There’s some I regret, but then there’s these lucky things that happen. I think the pink is really great…

GE: You have a pink book, don’t you?

AS: There’s a minor pink book, I have yellow books, for whatever reason. I like colourful books (laughs)

GE: Your books always stand out. Even NIAGARA being black, that’s a bold choice. I don’t remember which book it is, I remember seeing something of yours at The Photographer’s Gallery a few years ago that was pink.

AS: Brighton Picture Hunt was done with my daughter, that book was pink

GE: So you don’t really photograph your daughter?

AS: I’m like every other father, I ask her to smile; I’m that guy. I can’t do it in a serious way; I don’t know what it is. But it’s that way with my wife, it’s that way with my parents… it’s bizarre.

GE: I’m with you there, I’m the same. I don’t photograph my kids in a serious manner. They’re not part of the book. I find it’s a very separate thing. Maybe one day it will be another project, but for me it feels really separate; you have this and you have them.

AS: That’s really peculiar to me; in your case you’re photographing your family tree, but you’re not photographing this 1 extension of it

GE: I can’t figure that one out either. Even having them with me, you would think, I’ll just include them in some of the pictures I’m taking for Family Tree, but it wasn’t like that. I have a small digital camera that I use for taking pictures of my kids; I don’t have much on film of them at all. It will change, I would imagine, and I have thought I need to create a project but then there’s the likes of Sally Mann, she has intimate family photographs of which she documents her children’s lives beautifully.

Changing the subject a little, I was wondering if you do any lecturing?

AS: Yeah, I do. I was painfully shy, there was no way I could do a lecture or anything like that and I was kind of forced into doing that through photography. Ironically, the reason why I became a photographer is because I like being alone, but it’s opened up this new world and I enjoy it.

So this semester, I’m co-teaching a class with this writer I’ve been collaborating with the last couple of years, and it’s about this intersection between writing and photography. I’ve been collaborating more than anything else in the last few years. I’m actually now shifting back into doing something alone again. What about you, is that part of your life?

GE: It’s not a regular part of my life but I do enjoy it. I’ve given a few lectures at University of the Arts along with a few other places. I’ve also done a few colour printing seminars as I’ve always printed my own work in a traditional darkroom. I find it interesting that a lot of students aren’t familiar with this process. The digital age has really changed the necessity to focus on printing. I do enjoy it though, more so the speaking about work, and wouldn’t mind doing it on a regular basis.

AS: It’s only been a short period of time that things have changed. Being in a colour darkroom will soon be like doing a daguerreotype (laughs)

GE: (laughs) I’ll be in that category too, where I can barely walk and I’ll still be in the darkroom.

AS: How old are you?

GE: I’m 52, so I’m pretty old

AS: (laughs)

GE: Although I still play tennis like I’m in my 20’s. I was on a scholarship playing tennis in California at a school called Chapman. It was a great school and programme and I reached this point in my 20s where I was like, if I see another tennis ball, I’m going to slit my wrists. So I stopped playing tennis at the point, I really wanted to travel and pursue this type of thing. About 10 years ago, I started playing tennis again to get my mind off things, so it’s been this whole reversal process.

AS: I totally understand that. So my thing is ping-pong and it’s a significant part of my life right now. I love it soo much because all I can think about is the ball, and it’s such a release. So I’ve done a couple of art related things around ping-pong, and it’s been a delight. When I talk about wanting to make something joyous, those goofy little Ping-Pong things, have been these joyous little projects. They’re not serious, but I like it. Are you ever going to photograph tennis?

GE: Its kind of similar to my kids in a way, it’s one of those things that I love more than life itself, but I think, how the hell am I going to photograph it different than everyone else?

AS: There has not been an interesting tennis project; that is fresh territory, I would love to see that

GE: I was at a semi-pro level when I was in the states. I love it for the same reasons that you love ping-pong; it’s my place to go and kind of escape reality and I only think about how to hit a better forehand

AS: I think we should end on this note; it’s such a happy ending (laughs)

GE: (laughs)

Alec Soth, from NIAGARA

Glen Erler, from Family Tree

Alec Soth, from Dog Days, Bogotá

Glen Erler, from Family Tree

Alec Soth, from Sleeping by the Mississippi