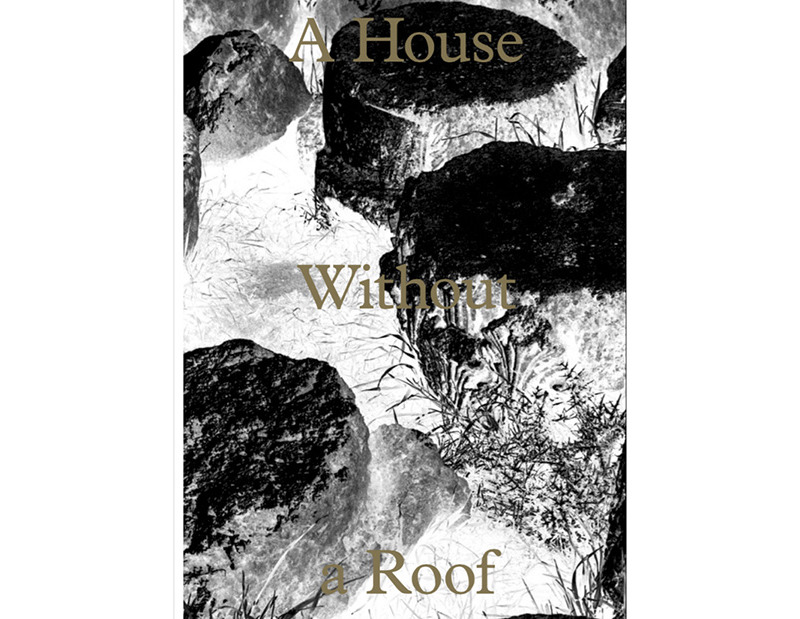

Interview: Adam Golfer – A House Without a Roof

A House Without a Roof (AHWAR) by Adam Golfer explores the contested, interwoven histories of violence and displacement across Europe, Israel, and Palestine. Golfer combines his own photographs with appropriated material and short fictional texts to examine the legacies of violence and trauma from different perspectives and points in time. The project developed over the course of five years and includes photographs and material gathered through fieldwork in Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Israel, Palestine, Britain and the United States. It has been presented in various exhibitions prior to the recent photobook published with Booklyn, which has been shortlisted for the 2016 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation First Book Award and the 2016 Mack First Book Award.

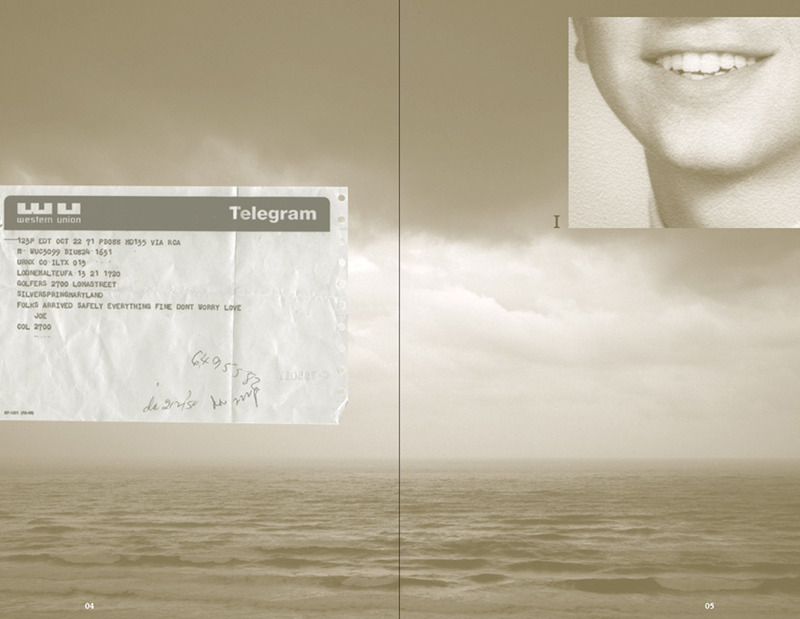

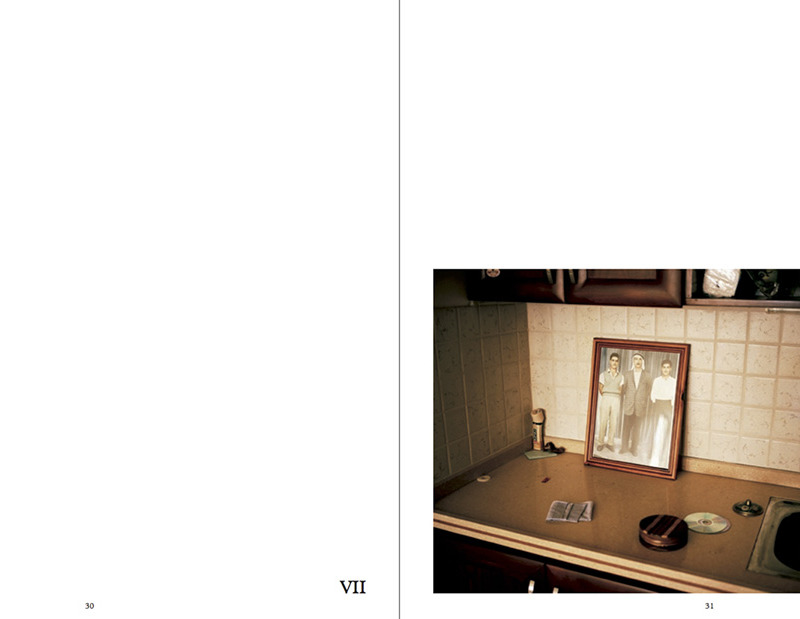

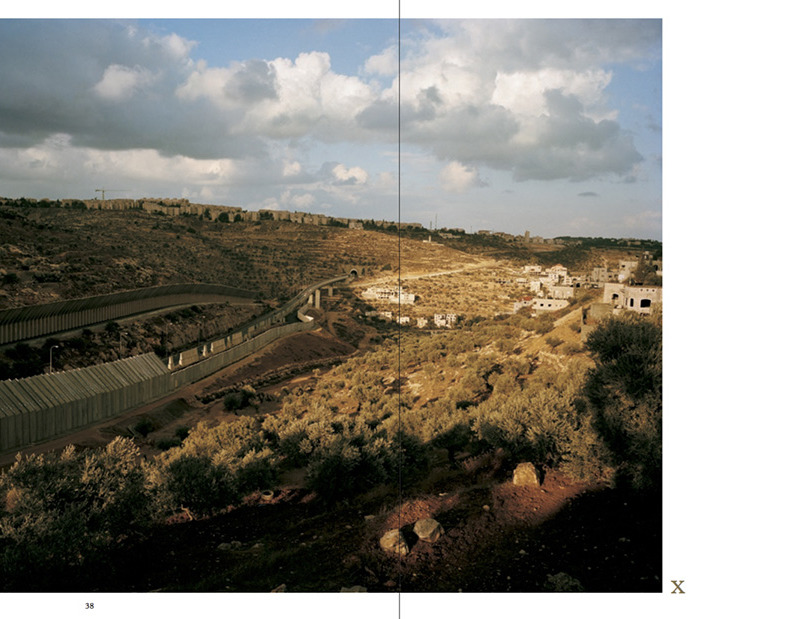

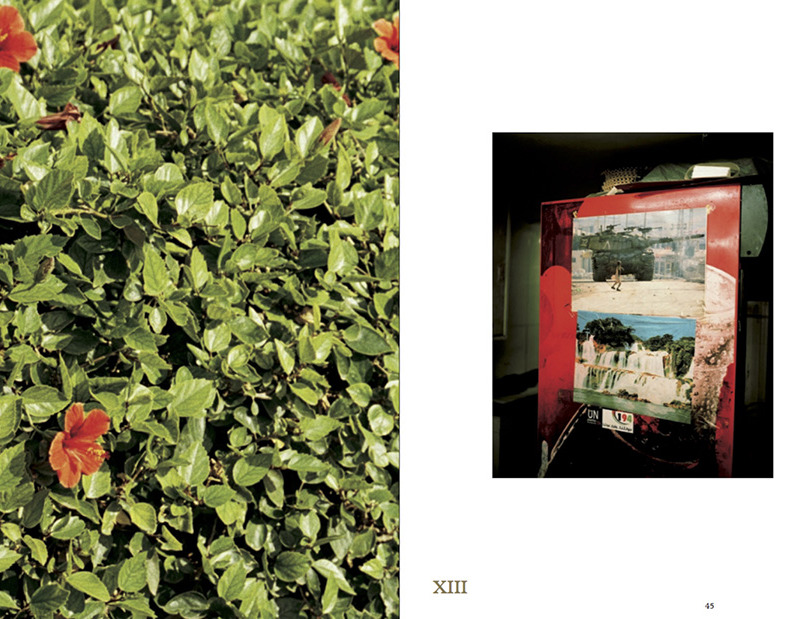

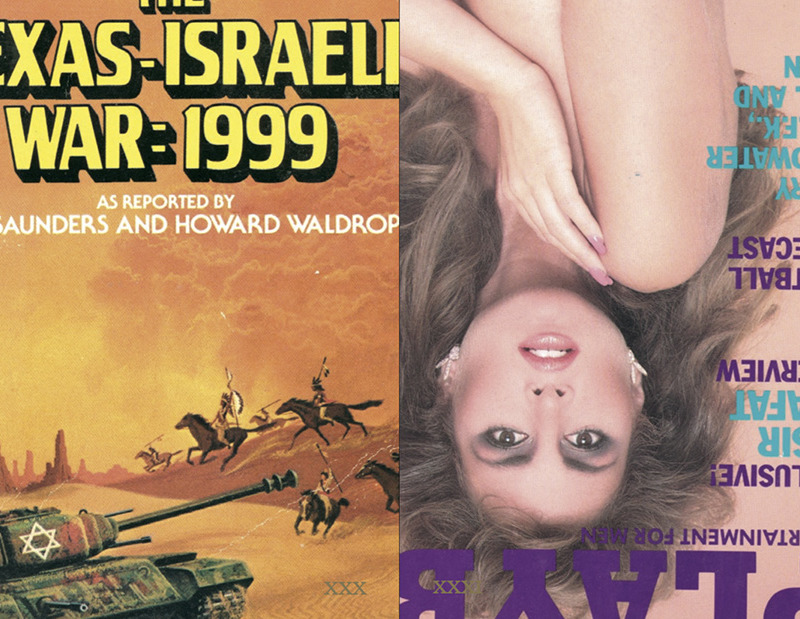

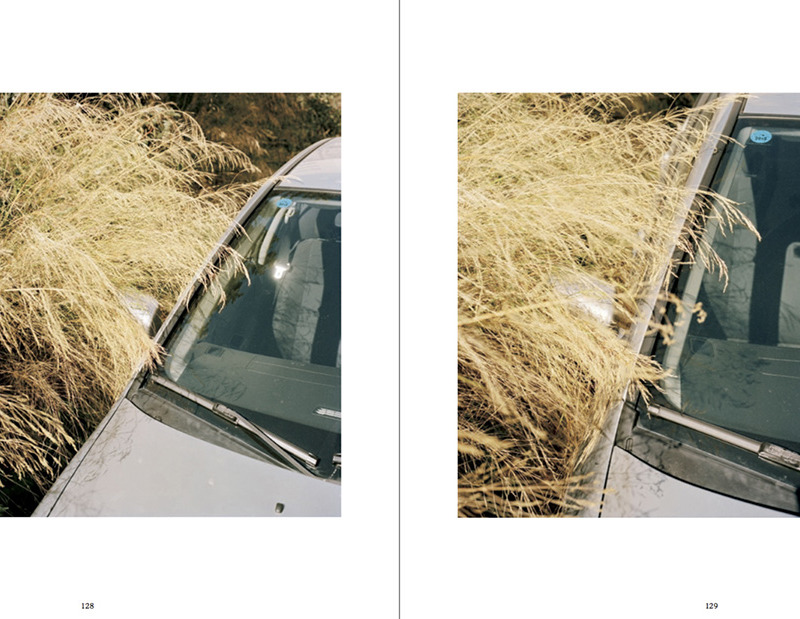

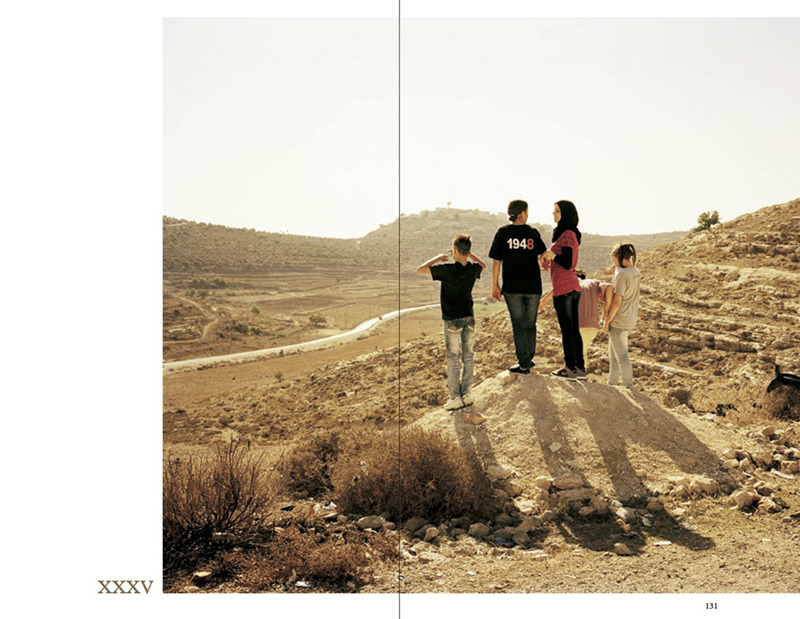

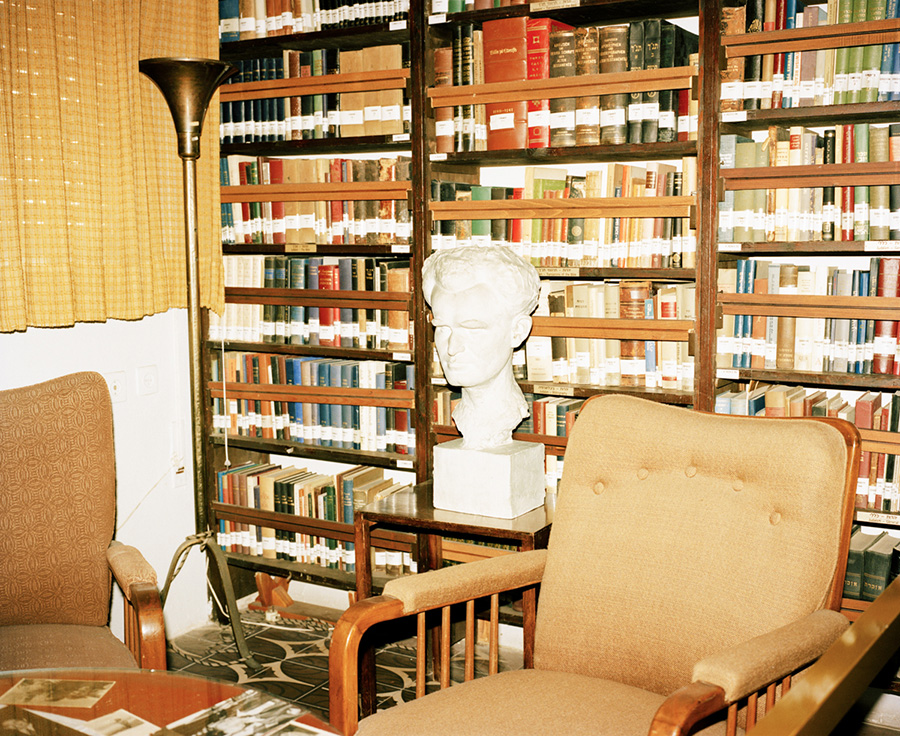

Golfer is a maker, researcher, archivist and writer and works across these disciplines in AHWAR to unpack contradictory histories and points of view. The relationship between images and text in the book is not always straightforward. Through either a linear reading or more haphazard browsing, echoes occur between image and text, mimicking the resonances of fractured memories or inherited family narratives. Seemingly impenetrable photographs – an olive tree, an area of cordoned-off undergrowth, a patio chair caught in barbed wire overhead – gain significance when viewed alongside the texts and archival images. In using personal experiences as starting points, the autobiographical becomes a multivalent lens through which to view a subject that cannot be pinned to a single history or narrative.

I spoke with Adam about the motivation behind AHWAR, the relationship between image and text and why the book format made sense for the project.

What was the starting point for the project?

My family history before the 1920s is unknowable. Aside from my grandparents, almost everyone on the Lithuanian side of my family was killed in Nazi concentration camps during the war. As a Jewish kid growing up in the suburbs of Washington, DC, this knowledge was largely responsible for the ethnic identification that I felt. It connected me to a recent, traumatic history that was visible in pictures and in the often-vague stories passed down to me.

After college, an educational scholarship afforded me the opportunity to spend time in Germany to try to make sense of a place that I grew up weary of. I became fascinated by the historical memory buried within the landscape and the institutional memorialization that has become part of society there. Evidence of the past is everywhere, and I made pictures that pointed to this violence without visualizing it, directly.

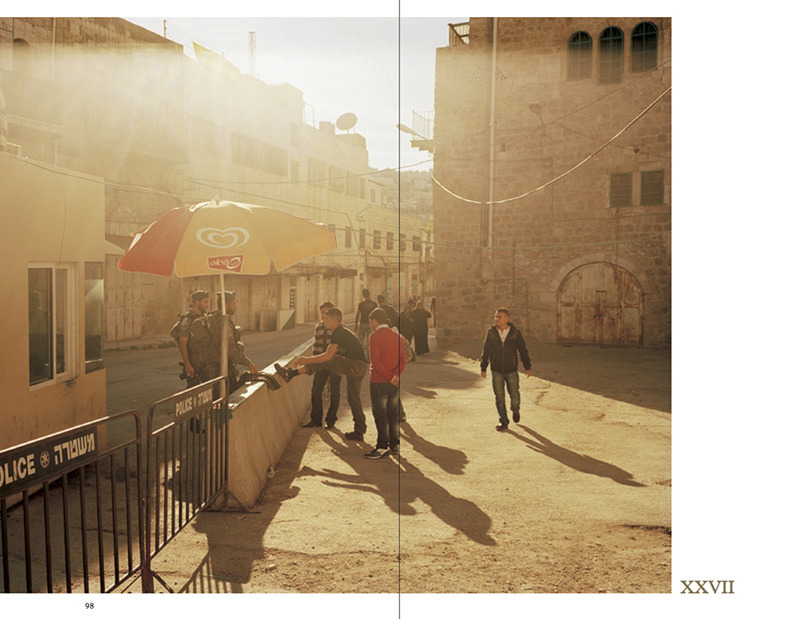

Ironically, coming to terms with my family history in Germany made me question everything I had grown up thinking about Israel and what it symbolizes. There are disturbing parallels between the histories of violence and displacement experienced by European Jewry during WWII, and by hundreds of thousands of native Palestinians during Israel’s foundation in its aftermath. The effects of this violence reverberate today as Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank and economic stranglehold over Gaza continue in the present. AHWAR seeks to connect disparate histories of trauma echoing back through the Baltics, Germany, Israel and Palestine.

Could you explain the process behind the images in the book?

My process involves long periods of research (both image and text-based), combined with fieldwork. I may direct a search around one event or person, and follow tangents in many directions simultaneously. Before a trip, I obsessively look at pictures of where I am going, mapping out places and individuals that I want to photograph. Connections between these subjects may appear abstract and random. Sometimes I know months in advance that there is a house or a statue or an idea that I want to take a picture of. Other times, while I’m walking in the direction of that house or statue, I’ll meet someone or discover something unexpected and never reach my original destination. The work takes shape during editing, when accumulated texts and images are arranged together, and begin to form a cosmology.

Why did you decide to present this project as a book?

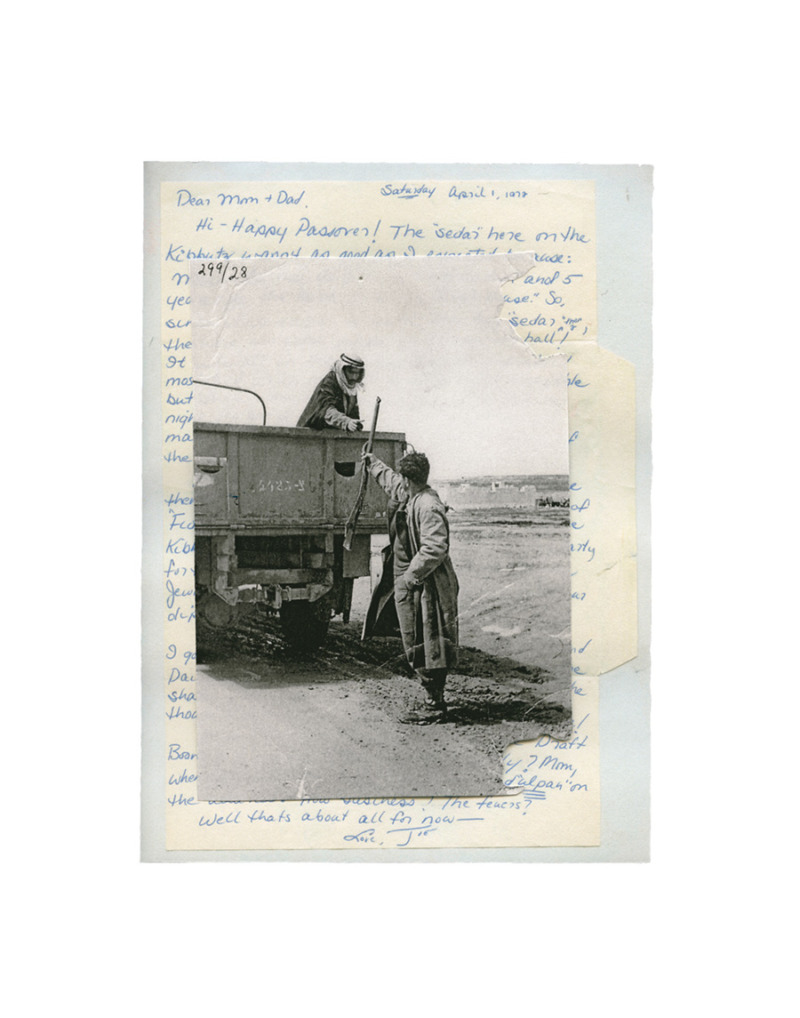

I struggled to find a form for this project for a very long time. The format of a book afforded me the space to grapple with multiple layers of information simultaneously: my own photographs, archival imagery, family correspondence, contextual information and a series of short fiction texts. Since so much of this project deals with multiple perspectives, contradiction and subtext, a book felt like the best venue for the work to live in. It provides a built-in linear structure, even when the order that I chose to arrange elements in is not chronological. A book can carry multiple registers of experience and time, and still hold together. There is also an inherent intimacy in the experience of holding a book.

From the beginning, I knew that since I could not speak for Israelis or Palestinians, I had to find an alternative way to convey narratives that resonated with me. Short fiction texts appear spread throughout the book, which are based on personal experiences that either did take place, or could have. Additionally, it was extremely important for the historical context of the pictures to be legible. In Israel and Palestine, facts are leveraged and refuted, everyday, to support or discredit political agendas. As a result, contextual information about many of the images in the book appears in an appendix.

How else have you shown the work? What does the book format offer that an exhibition doesn’t and vice versa?

I have presented AHWAR in a series of installations. The photographs appear framed on a wall, leaning on shelves, loosely tacked and generally arranged alongside archival materials, salon-style. For a recent exhibition, three slide projectors illuminated seven of the book’s short stories, continuously looping and falling in and out of sync. The projections were smaller than 10 inches across, and appeared at different heights among the wall imagery.

The book is the ideal way for the work to be seen. I think most people will give more attention to a book, because of its intimacy. In a gallery setting, some subtleties of the work are lost. Although I provide an image key for the photographs and objects, a gallery audience generally has a limited attention span for texts. At the same time, when working with installations the work is constantly evolving. In these instances, I need to gauge how much ambiguity or transparency the work can convey in a physical space.

There are some interesting design elements to the book, such as the use of gold and different paper stocks. Could you explain some of these choices and how images are treated differently?

The gold in the book became a reference point and symbol of Jerusalem and the Levant in general. The Dome of the Rock sits atop the Temple Mount, as the symbol of the old city of Jerusalem, holy to Jews, Christians and Muslims. Located within the walls of the Dome of the Rock is the Foundation Stone, where in the Old Testament, Abraham is said to have offered to sacrifice his son Isaac to prove his devotion to God. In Islamic tradition, Mohammed’s Night Journey from Mecca to Jerusalem brought him to the Temple Mount. To me, gold is the symbol of the historic attachment and claims each group has to the same land.

My good friend, Ghazaal Vojdani directed the design of the book, and she suggested using gold as a way to separate archival and found imagery from my own photographs. This was a system that we stuck to 95% of the time. There are two paper stocks in the book – one for images on traditional photo paper, and one for texts on an off-white uncoated paper. Although flipping the pages you will see images and texts mixed together, I wanted there to be different experiences with each element. We also knew from the beginning that the book would be trilingual, in English, Arabic and Hebrew, and it was very important that the texts on every page appeared in all three languages. I wanted any communities that are the primary subjects of the book to have access to it.

What is the relationship between text and image in the book and how have you used the book format to influence the way readers will encounter them?

Over the years I shared the pictures with friends, and without realizing it would end up narrating each image’s backstory. “Why don’t you write something,” was always the reaction. But I really struggled with this because I was afraid of this project becoming too much of a sentimental memoir. Eventually, my professor in the MFA program at Hunter College insisted that instead of just recording things that happened, that I try writing fiction, to see where it would lead.

The texts that resulted were very raw and expressed a lot of the ideas that had been floating around my head for years. Fiction afforded me a distance from experience that felt honest and somehow closer to the “truth.” Even so, I was terrified at the thought of including them! But my friends insisted that the stories belonged in the book. Now they carry the same weight as the images.

The stories are interspersed among the pictures to interrupt and pull the reader out of different sequences. Sometimes they reference images that appear earlier in the book, and other times the reverse is true. The texts inject a great deal of personal context in a way that the images alone cannot.

Many of the photographs have contextual caption information in the appendix, but others are more intuitive, and appear without explanation. I enjoy the sense that you can’t fully understand everything about the book. Hopefully that leaves space for the reader to fill in their own ideas about how these histories and overlapping narratives are presented and what the relationships between them could be.

Do you have any particular influences, either on the aesthetic of the work or your approach to working?

Susan Meiselas’ Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History had a profound effect on me; particularly, the manner in which Susan simultaneously took on the role of curator and detective. Over the course of many years, Susan pieced together narratives of disparate Kurdish histories by collecting and arranging photographs, interviews and correspondences that she gathered from many different communities.

In AHWAR, photography, collecting and writing relate aspects of personal histories and global narratives. Writing in different voices, the book is largely about my desire to come to terms with the violence and contradictions of histories that expand outwards from my personal experiences. In terms of varied approaches to representation, psychology, memory and history, the artists Basma Alsharif, Omer Fast, Hito Steyerl, Michael Rakowitz and Kerry Tribe all continue to challenge the way I consider aspects of my practice.

How does the book relate to other projects or bodies of work?

My interests reside in the spaces between historicised chronologies, where complexity and contradiction challenge the way we understand the past, the present and perhaps, the future. While in the MFA program at Hunter, I began working with video and it opened up new approaches for my work. Although the medium is different, my film projects continue to probe the sociological and psychological spaces between how events are recorded, refracted and retold.

In my films, We’ll Do the Rest and Router, individuals who should never meet are placed side by side, to provoke new relationships with one another and to the audience. Frequently, the conversations take place across time and space, between my collaborators and me, and between the layered histories that I parse.