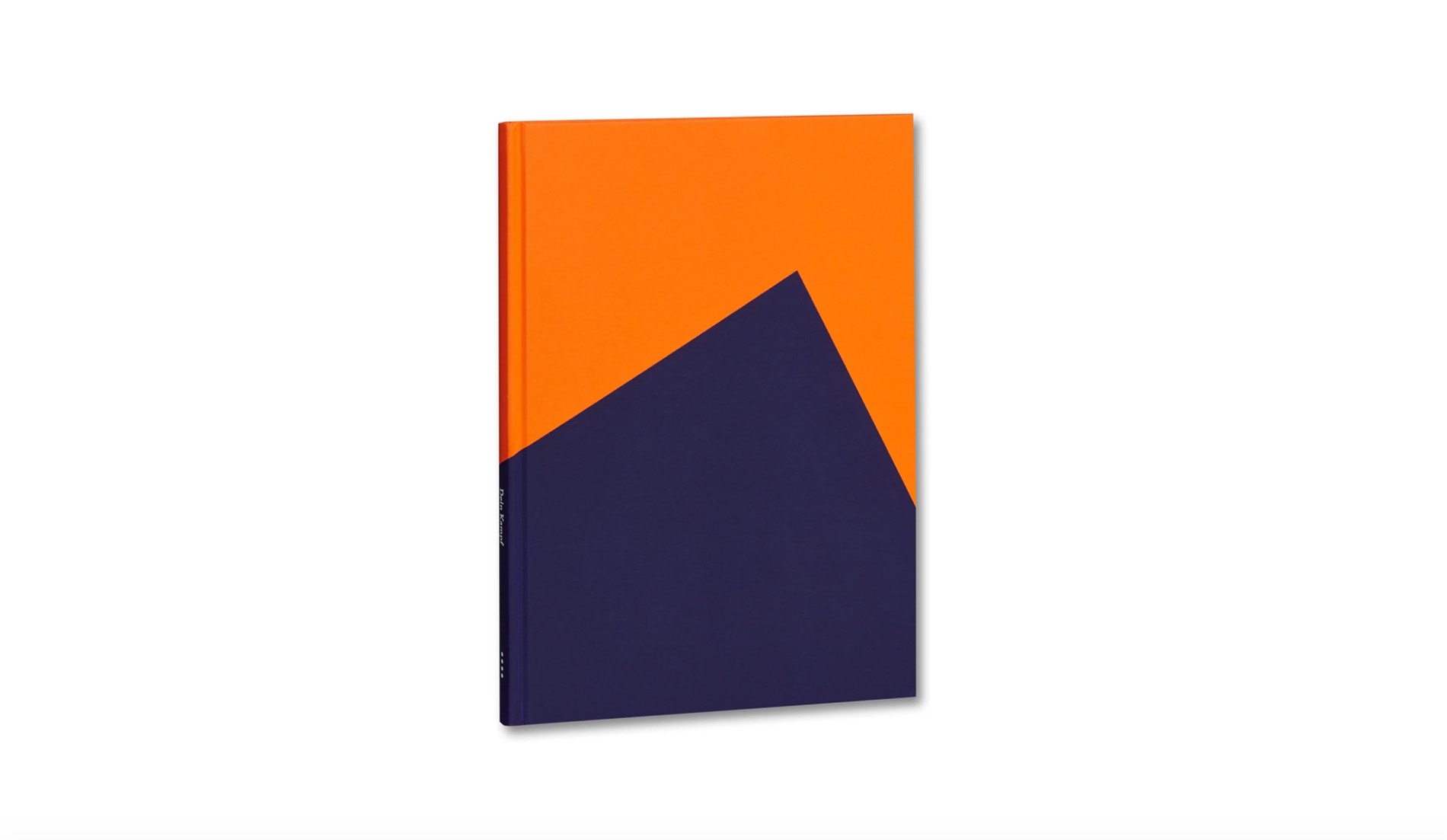

Interview – Brad Feuerhelm, Dein Kampf

I read recently how European cities are like museums. They are different from the way in which many cities in the world, outside of Europe, consider their development. Europe’s major cities are protected to a degree as relics of modernity, built on imperial wealth and industrial might, featuring not only the physical beauty and scars of the relatively recent past but also latent, psychic energy. Berlin could be described as a museum par excellence, a popular site for historical re-visitation. Its twentieth-century history is probably the most compelling of all European cities, and it is under this weight that certain powerful imaginations have emerged in art. One such recent example has been created by Brad Feuerhelm, whose book, Dein Kampf (MACK, 2019) became the subject of this conversation.

Sunil Shah: Let’s begin by talking a bit about how and when the photographs in the book were produced. I was there, at least when you were scanning and editing. For the readers, we should talk about Michael Grieve’s workshop with John Gossage and you running it, and while the participants of the workshop were out shooting, I guess you were, too?

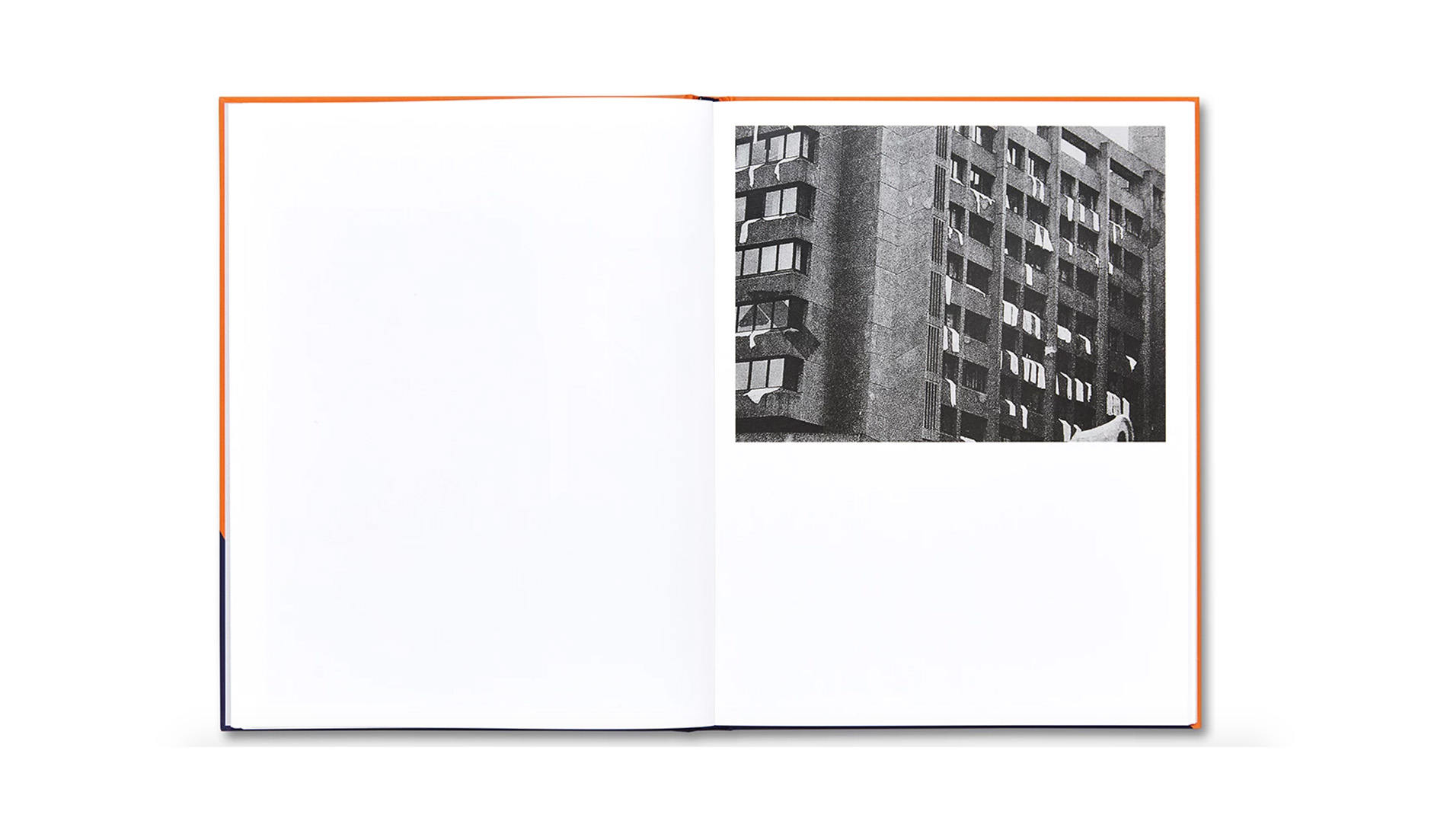

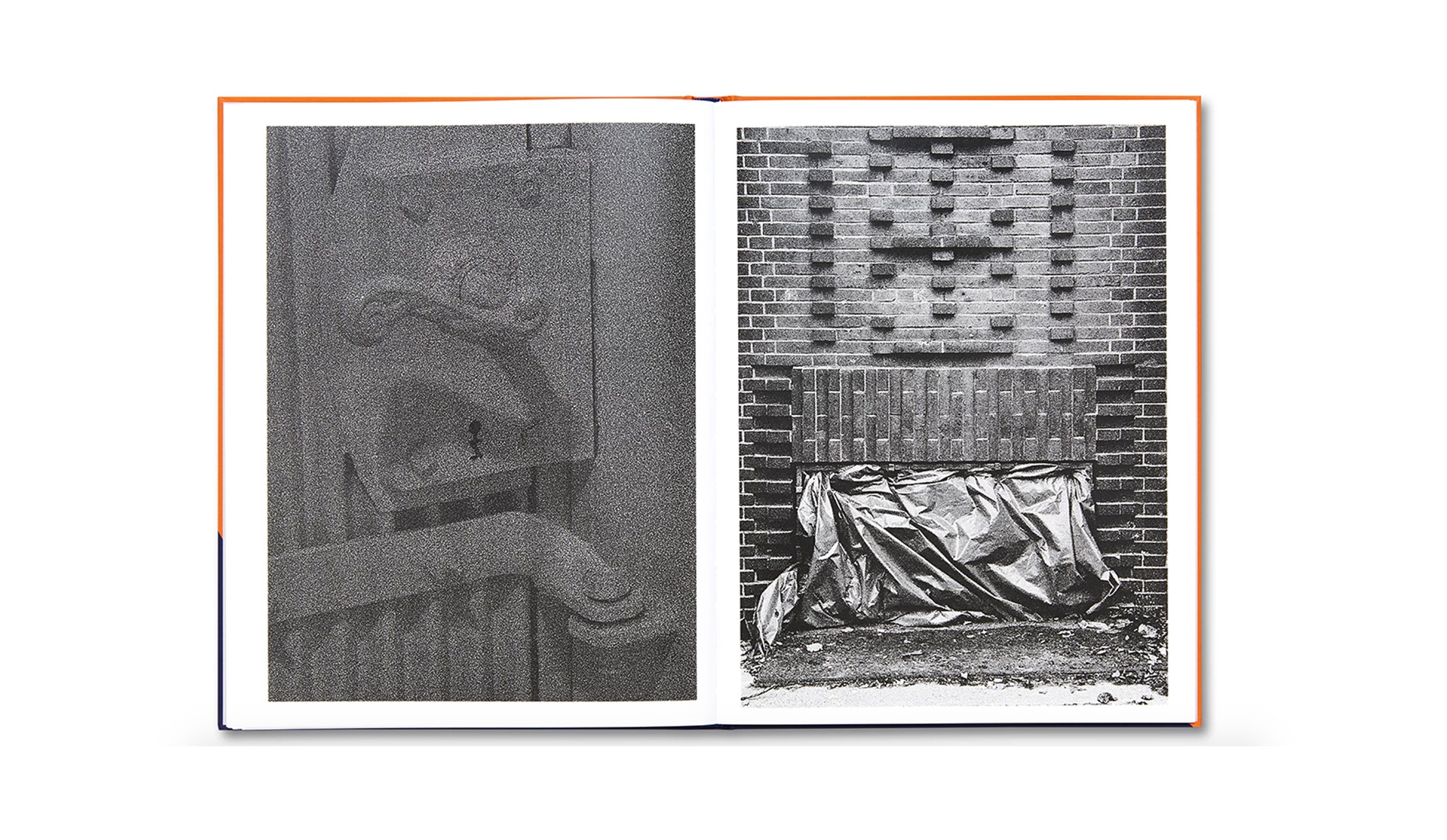

Brad Fuerhelm: I guess in full declaration of how I work, it would be fair to mention that I shot the images first and quite quickly felt they were a book. I did not start by shooting and looking to produce a publication, as a few things had changed in the way I look at how photographs are produced. I was looking for a reduction of terms but had also been highly influenced by post-war German photography. Michael Schmidt’s work, in particular, had an influence in the way he used inconvenient spaces in his images. In correlation, John Gossage, had also produced a fine block of images about Berlin in the ’80s. Both were incredibly influential and still are on how I ‘see photographically’.

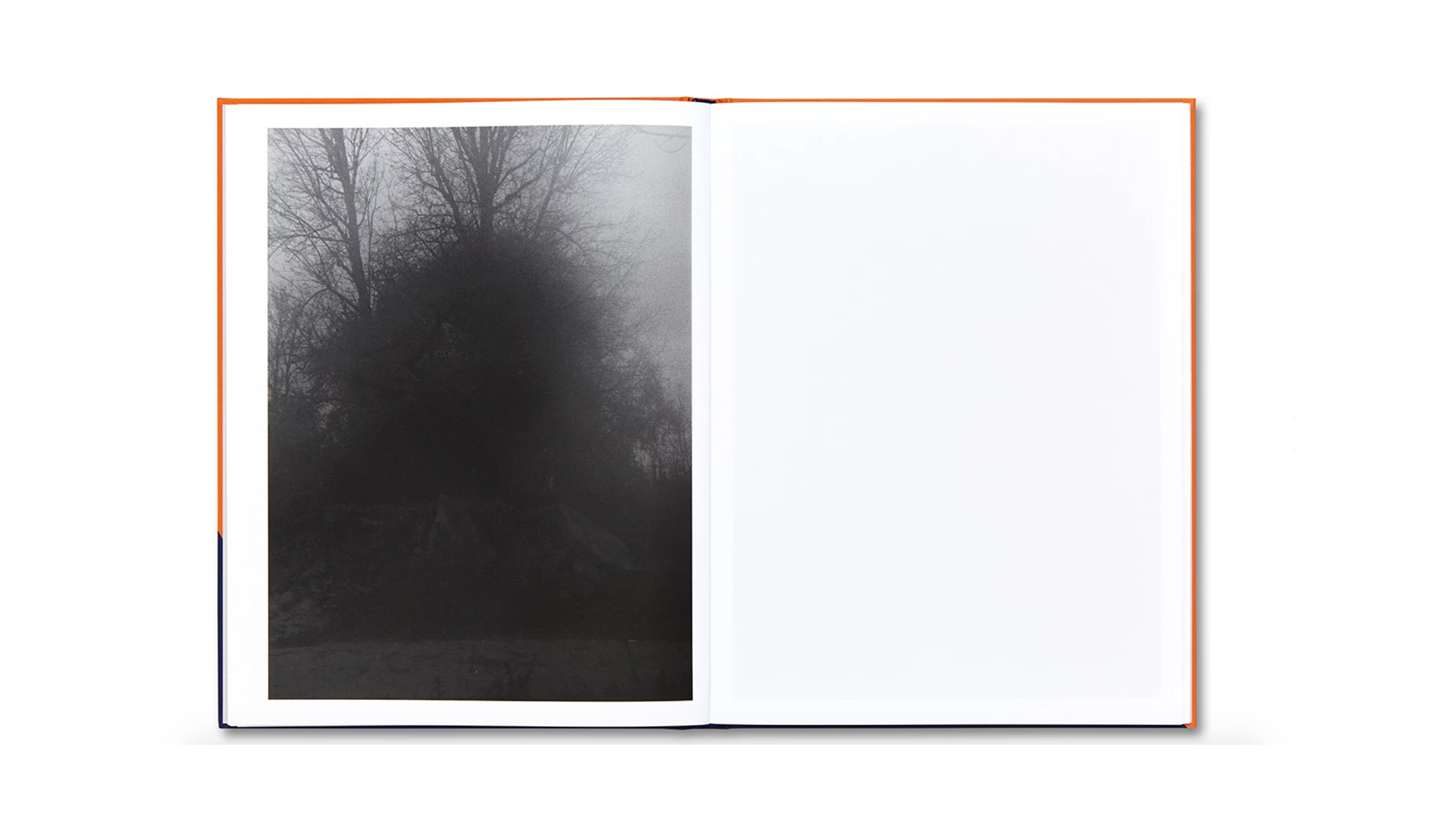

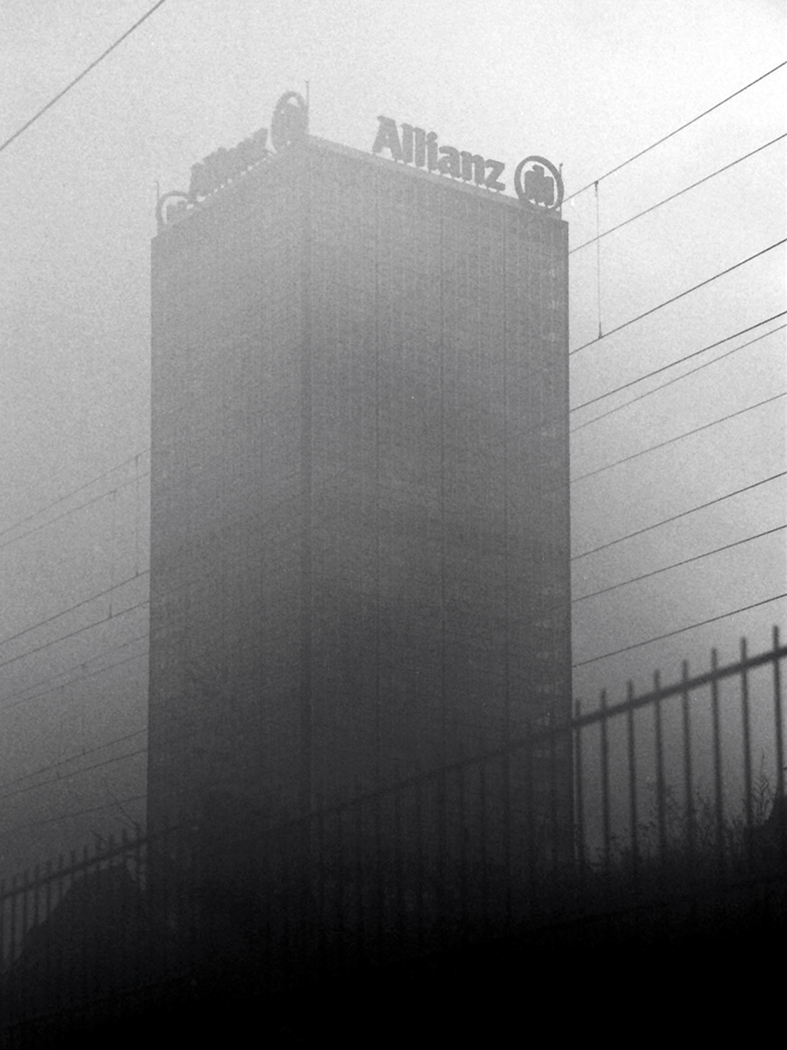

I made the images during the three days prior to the beginning of the workshop. It was super intense; I walked Berlin for up to 8 hours a day looking for something dull and aching in the landscape. I was already semi-literate about the city’s history in photography, but also its history, so the pulsing knell as well as push and pull of fragments and ruins, beckoned. I stopped when the workshop started; I would not have been able to divide my attention fairly otherwise.

Dein Kampf is less about violence or physicality of dissatisfaction, it is more a lament and a way to metaphorically engage the process of image-making to enlist a sense of questioning; how we view an image and how that image transmits an inverse application towards ideology.

It was a pretty intense few days, I remember visiting the Schmidt archive with the group to meet Thomas Weski. That was amazing, as were the workshops, framed by John Gossage’s insight and your ability to activate a useful discussion and production space. Can you tell me more about your approach to making the images? I’m interested in the “push and pull”; what comes to mind is that there is a sense of familiarity in the book, but also a strong revelatory feel. Did it feel anything like that to you?

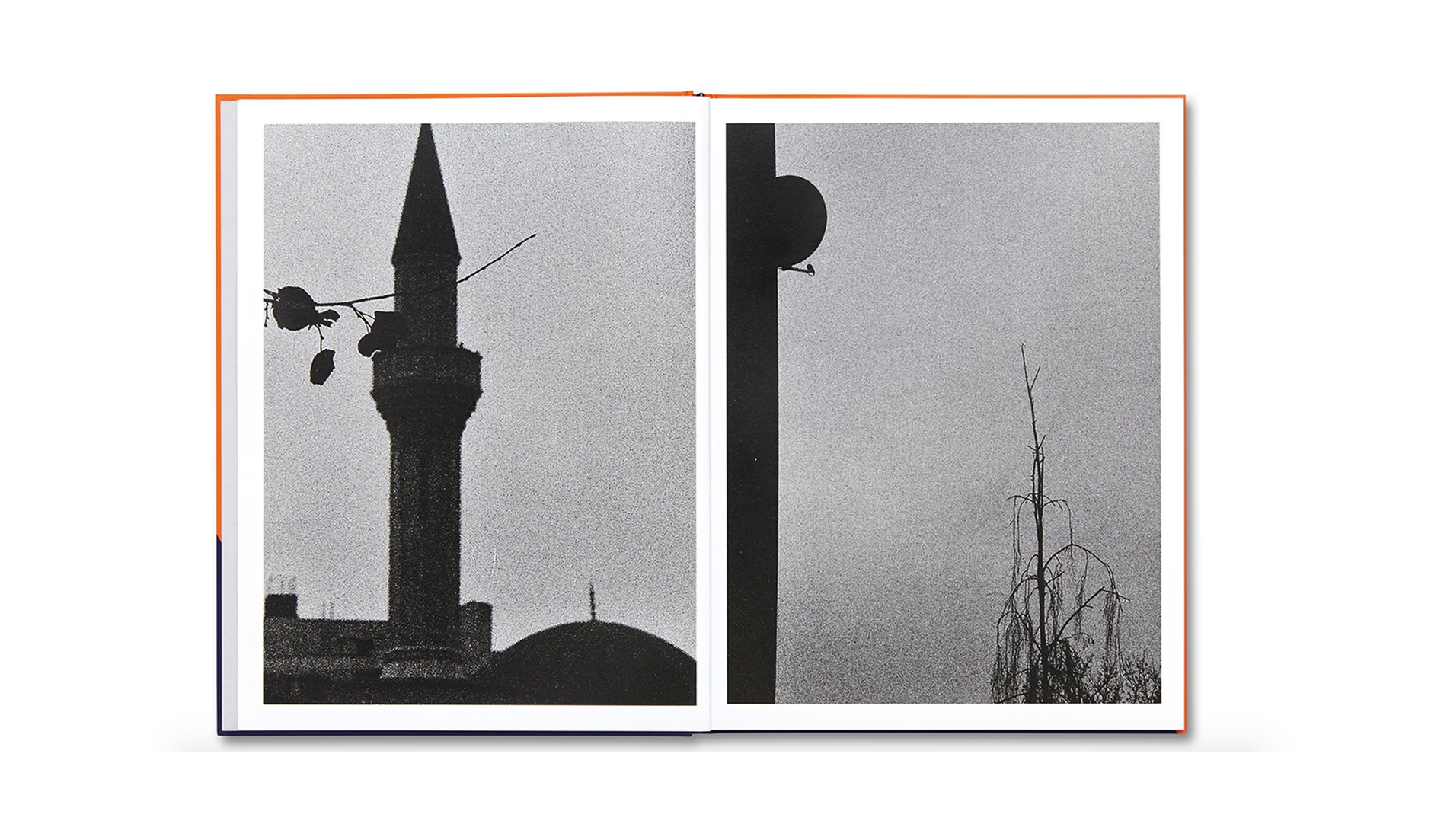

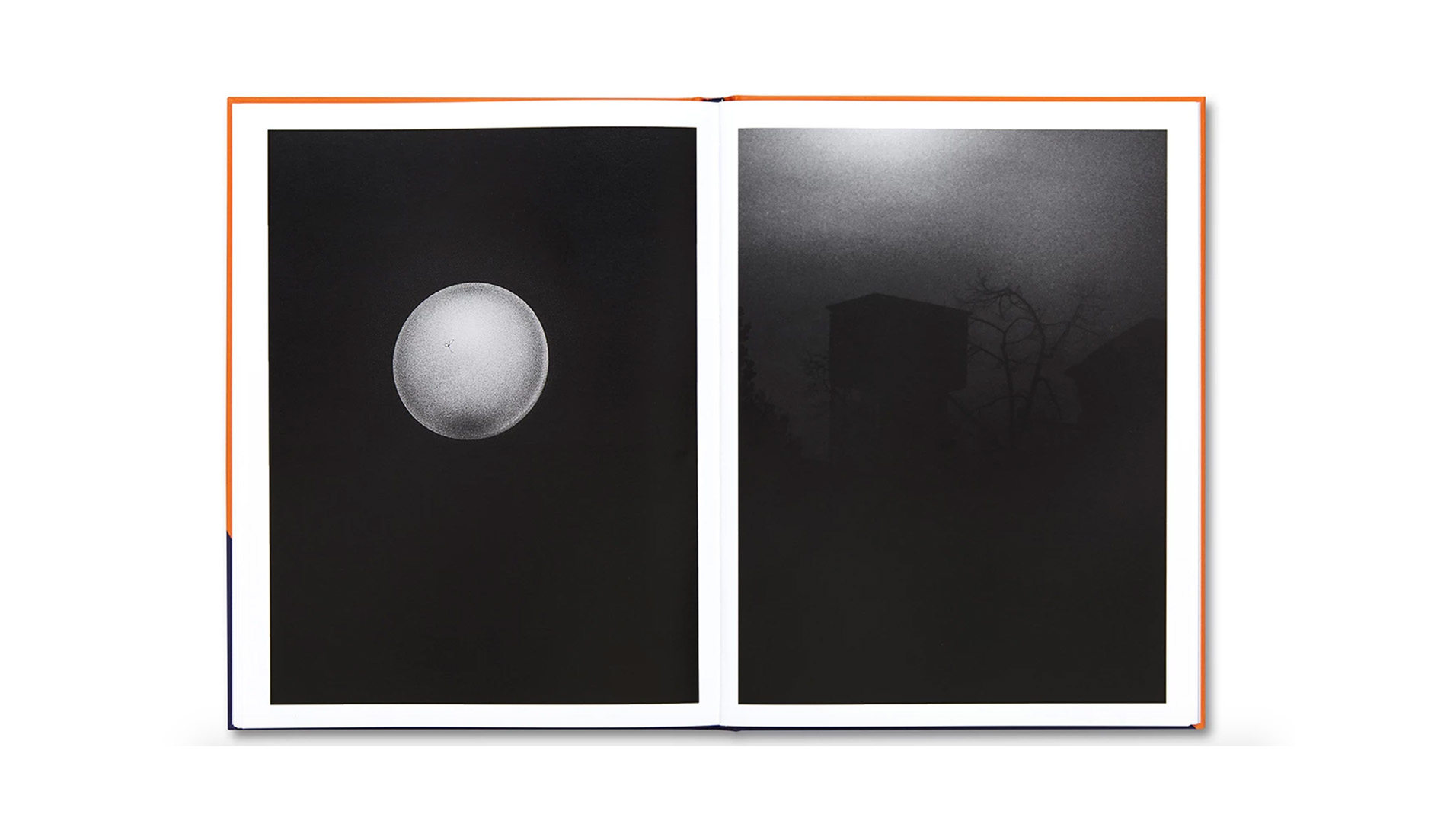

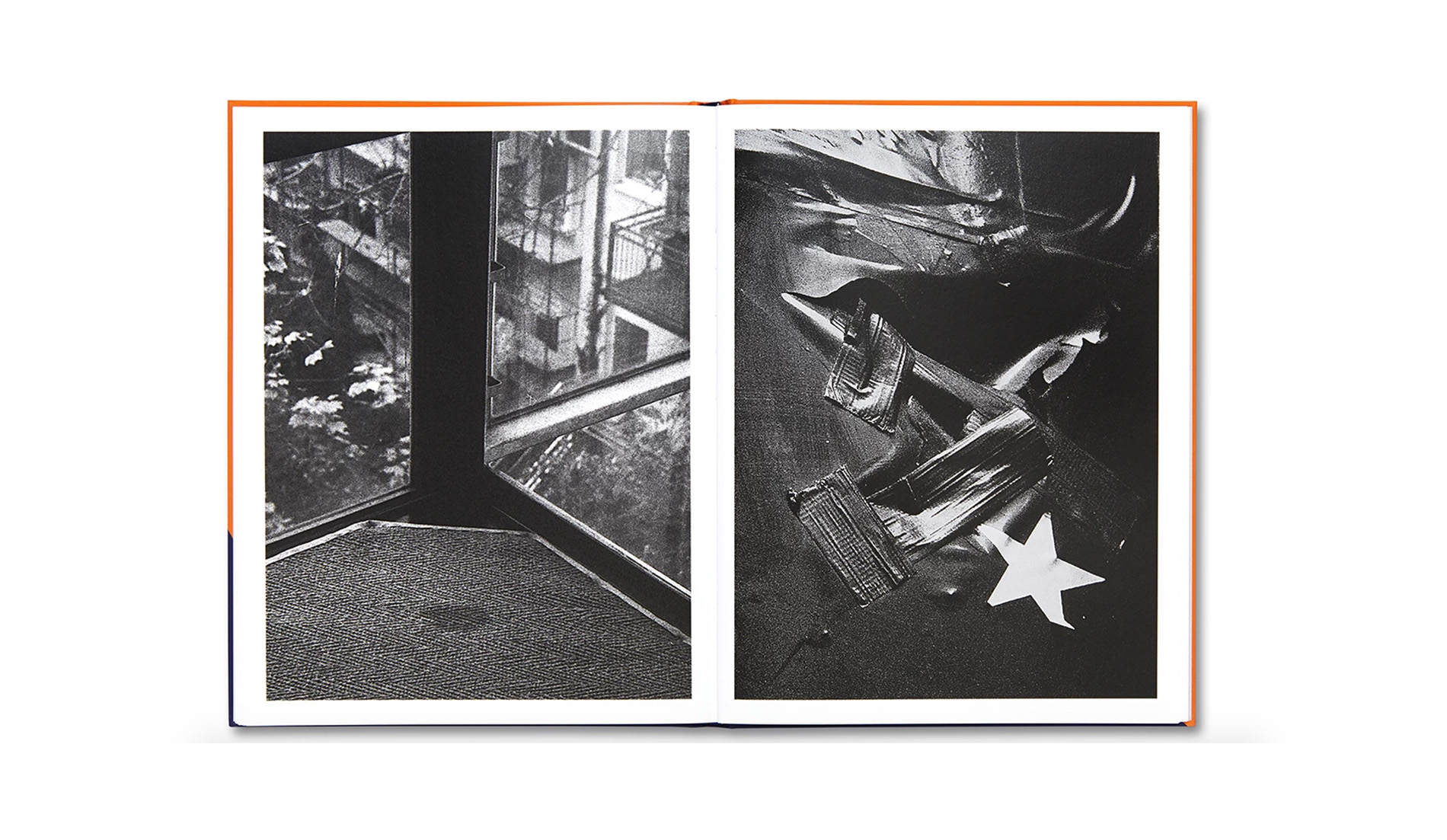

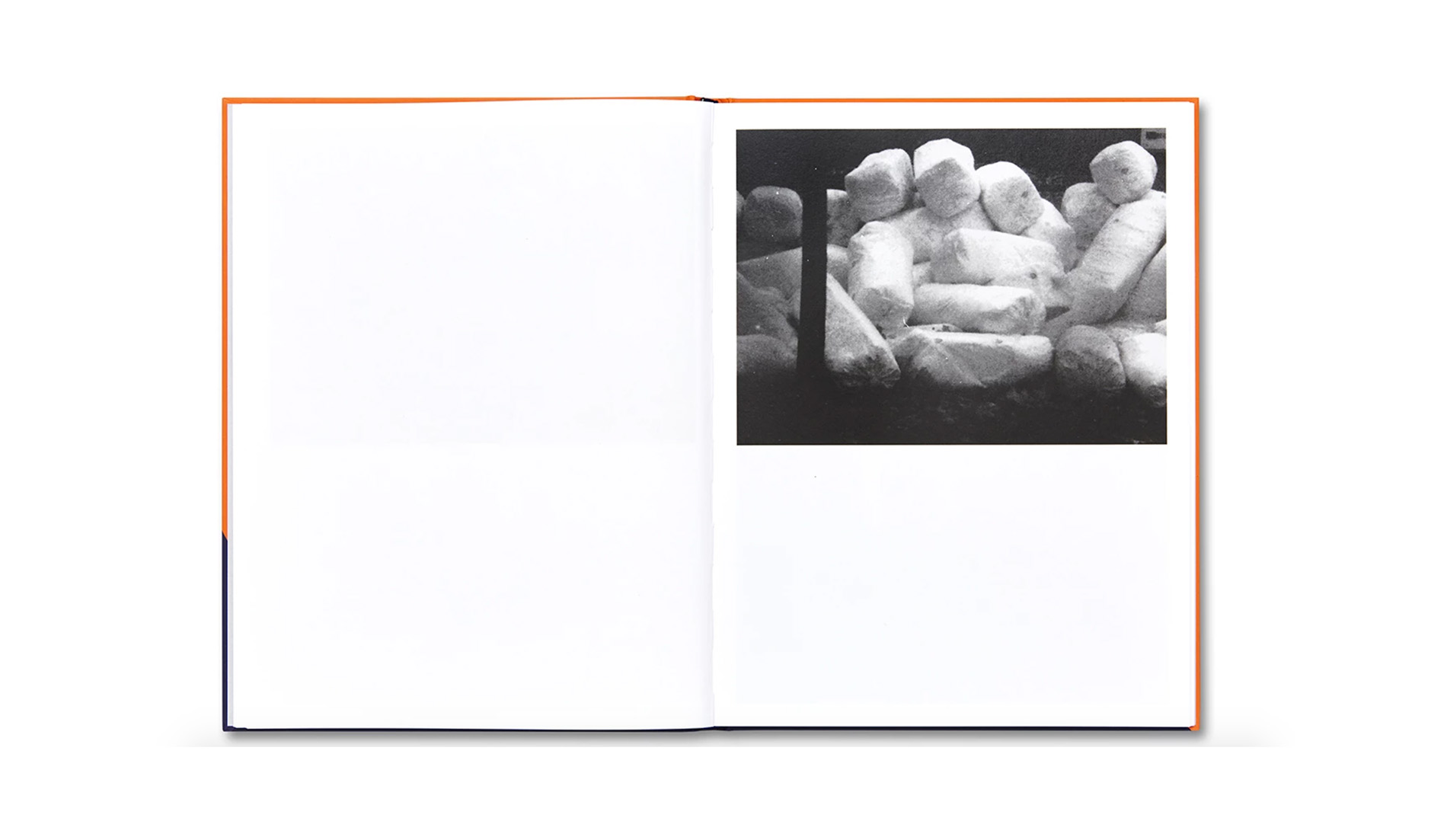

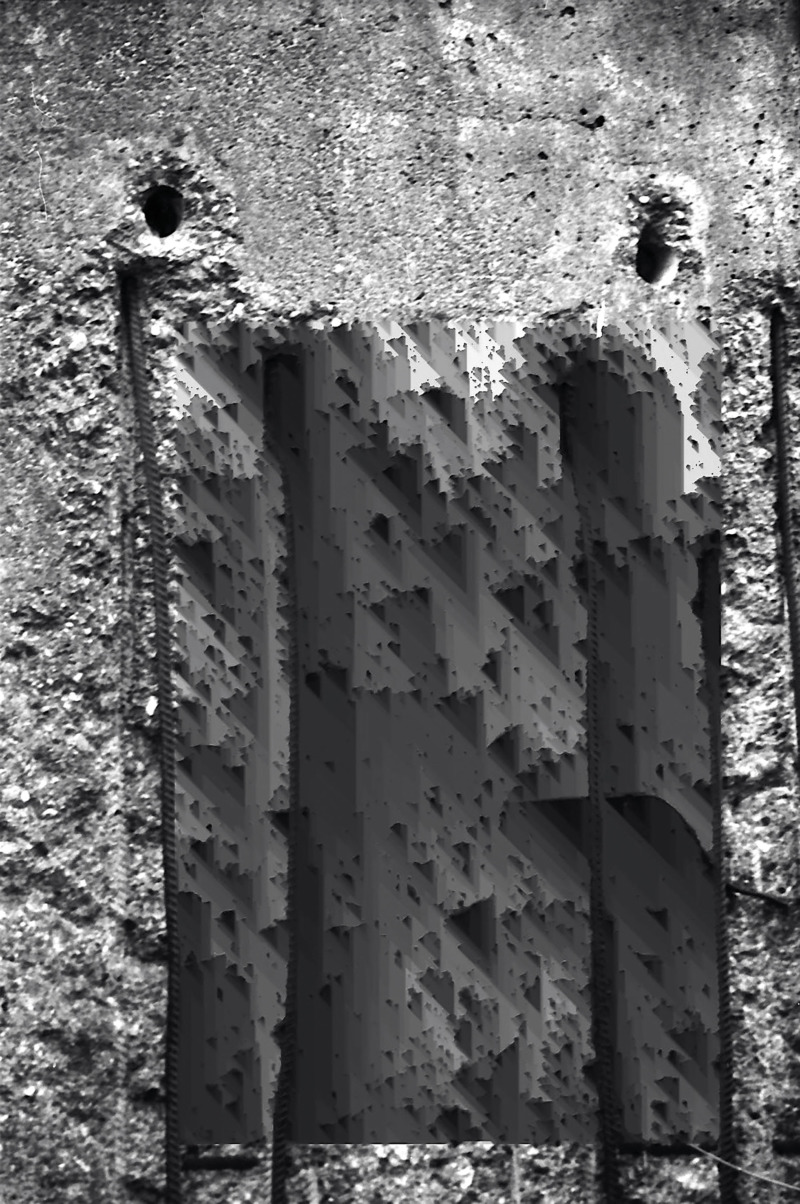

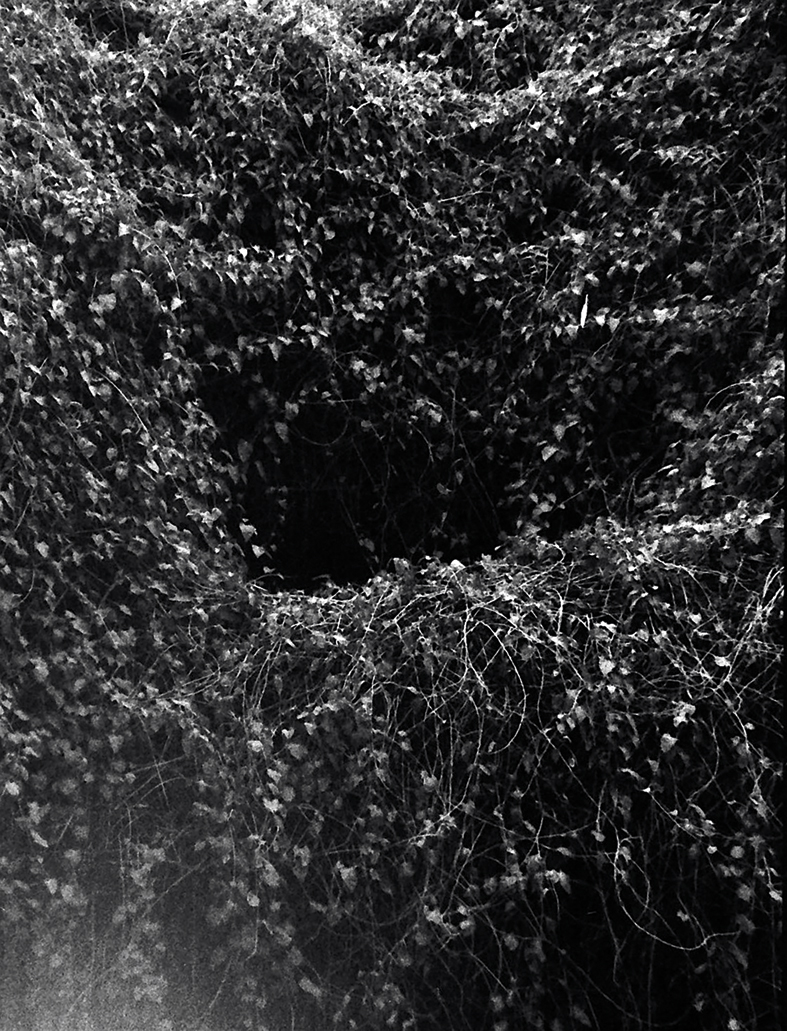

Shooting for this project, in particular, is perhaps secondary to the editing. It wasn’t assembled from disparate parts per se, with all images being lifted from the landscape of Berlin, but I would say the editing was more important as was the “post-production”. Michael (Mack) had seen a portfolio of the images and when I made the first physical maquette he noted that the images were “hairy” or dissolute. I am an anti-technician of sorts, always looking for errors or mistakes’, not chance. Chance is an aberration of the incidental and wrong; I am looking for error. Michael responded positively to this and I pushed the envelope a little further by scanning the negs, printing them, and then re-scanning them at a different size that would allow them to be difficult to read up close, and easier to read from a distance; a metaphor for the basis of its intention, to limit the photographic image’s ability to promote ideology, to tear and render its significance into decay.

It’s an approach you’ve adopted previously, right? I remember Goodbye America for example, there wasn’t decay, but physical destruction of slides. Is the idea of obliterating the image, wrenching it from its reality, a gesture towards dissatisfaction with ways in which the photograph is employed, or is there something more satisfying in a subtractive or abstractive process?

Yes, with Goodbye America it was more an act of oppression, to use the hammering tactic of the slides as a way to symbolically work from a position of iconoclasm, dismembering the false realities involved in the American dream. I saw that as a way to enforce a different kind of dissolve.

Dein Kampf is less about violence or physicality of dissatisfaction, it is more a lament and a way to metaphorically engage the process of image-making to enlist a sense of questioning; how we view an image and how that image transmits an inverse application towards ideology. The conceptual framework is that the images, in their failing state, represent a tool to speak about wider issues that prevail in hosting an ideological position too close. If you look at the book too close, the images fall apart, like an apathetic pointillism. When you hold it at arm’s length, like ideology, the position of the image and its meaning becomes clearer.

This idea works, especially when you look at the history of post-war abstraction in art. Abstraction wasn’t about making things indistinct but drawing further towards an essence. When we consider the aftermath of WW2 in Berlin and its latent trauma, it makes sense that the depth and intensity of this history cannot be taken lightly, especially in photographic form. I think that’s why Michael Schmidt’s work is so powerful, it exposes something of a psyche without reducing anything down – something which I think Dein Kampf shares. Can you say more about your thinking on post-war history in Berlin and how that relates to the photographic? I know it’s a subject you’ve spent time with.

Berlin is a very particular and singular place where all of this trauma of the land sort of overlaps and imprints itself on its history, memory and social bodies, even if they are not native. It’s a place you certainly feel. Ulrich Baer in his essay in the book goes into great detail drawing from interpretations of Berlin and photography from Kracauer, Benjamin and so on. I think the overwhelming idea about this project is that although it was staged in Berlin, I do not consider it about Berlin, but rather I have used the city and its history of an ideological collision to speak more about our current pathology of ideology. It is meant to reflect, as the title suggests, a push against the notion of subjective interest (mine or Schmidt’s) in struggles that define a person. If your struggle defines you, you have lost sight of history. It is a lamentably relatable issue in so much as that currently, we find ourselves deluged in the morass of political tribalism. So, my approach is actually to speak about the present through an act of historical aggregation.

That is super interesting, as I was just reading about modernity, postmodernity and the ‘end of history’, so to speak. This political tribalism has resulted in deep subjectivities that often entrench individuals into positions that are difficult to re-emerge from. Perhaps in this, there is a need to re-visit history as a way of redefining the present, in the way much archival based practice does. It’s interesting how far this takes us from the idea of “photographer” in its practical sense. We have become editors of content, content that has ramifications, beyond the representational and into the ideological and analytical. I find it difficult to think of a push away from subjective interests, though. Do you think resisting these deeply entrenched ideological positions will gain more traction in photographic practices more generally, or is the medium too rooted in its liberal outlook?

Good question. The purpose of the title is a firm statement that I want to return the fight or struggle to those who actively wish to be part of these kinds of political questions. I want no part of it. Left, right, identitarian, alien, or other. Photographically speaking, I do not believe that we can adjust perceptions to accurate guards of representation. I do not wish to speak for others, nor do I wish they speak for me. The problems of outlook have to be confined as of one. This, in essence, is where the work stands. I can only give some small summation of my person, its subjectivity, etc., in making images, therefore a liberal outlook is not something I feel adequate to assess anymore.

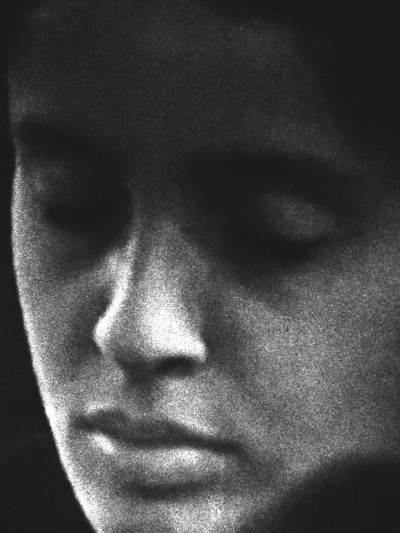

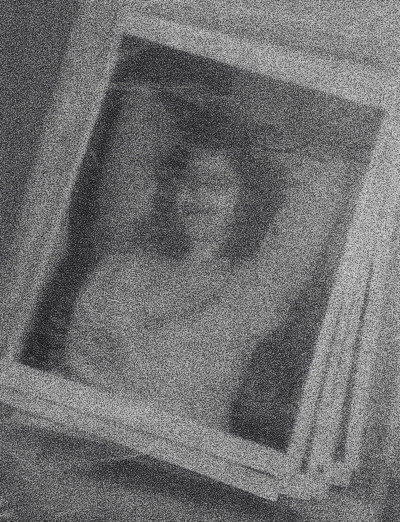

In fact, this space of an individualist perspective, resisting representation, appears to me to be where “good art” seems to be right now. In presenting a kind of neutrality, there is an effect to be encountered instead of knowledge to be learned. As an entry point to this effect, I wanted to return to the editing process and to pick up on a certain motif in the book, that of the woman, eyes seemingly averted to the sights that follow. It is on seeing this woman that I think the viewer humanises what is to come, is that how you read that presence or sequential device?

I think we’re trying to correct some wrongs in terms of how we believe photography has worked for people in the past. I do not want to speak for others; I do not want to cash in on their burdens, nor do I want to invade their struggles with my voice. It’s not because I am a warrior for cause, actually, it is the inverse of this; I am a warrior of one tongue. I can only relate to the world as I “read” it. I think the greatest of failures occur when white male privilege tries to undermine or exact responses to the struggles of minorities as we are currently witnessing. This hand-holding, when it is convenient, leaves me feeling a bit ill. I base my response in a similar way to the means of my disposal. Nothing more, nothing less. The “women” in the book are not people. They are illustrations found in the city on posters etc., that I have cropped in such a way, using objects like street lights, for example, to truncate their faces or to elicit a sense of the cinematic. Gender is of course punctuated in so much as I generally choose to work with an image of a woman. I do not trust or like men much…

In terms of your voice in this book – and it is your voice entirely, I’m aware that many will bring their own interpretations to the book, including me, which must be a great thing for you to hear (sometimes, haha), so I wanted to ask how you juggle being a significant and highly respected critical voice to contemporary photography and also being a maker; does your own criticality invade your creativity and production processes or does it actually shape and support it?

Ufff, I don’t know about respected, hahaha. That is a contentious thought for many, I am sure. I have seen with this publication that the ability to defend the castle of critic, artist and bookmaker is being tested with questions around fraternity, which is completely ridiculous. Nobody publishes a book based on a few nice reviews. None the less, this wider remit of wearing several hats has given me the position of privilege in that after many years of unpaid work, the educational value has paid off.

The criticality is, of course, part of the wider benefits system of working on so many unpaid reviews of books. I literally write 3-5 reviews per any given week between American Suburb X and my Instagram account and am constantly looking at books as they are received. I guess I get about 5 per month that are unsolicited and up to 10 more from many different publishers. What this means is that I am very, very familiar with how publishers see books and how artists/photographers see books. It has taught me a lot about the ‘don’t’ side of things. I am also pretty critical of my work. I tend to chop more out of sequence than perhaps is necessary and do so simply as I want to distil it to some sort of essence. This can make the edit claustrophobic.

With Dein Kampf, it was clear to me very early on through the images alone, that it could work within MACK’S orbit. Having a working knowledge of the top publisher in the game’s offerings helped to consider what it might look like reformed, validated and constructed in a way that reaches further than one Offprint table. Understanding the mechanical nature of a publisher before you submit is the greatest advice I can give anyone. Realising that you will need to kill your darlings early is super important when working within the wider gamut of offering a maquette. Study. Edit. Edit again. Submit.

Finally, there is something that I’ve completely missed – that this is the first book of photographs you’ve shot and published as opposed to a work of appropriation or re-framing of found or archival images. I think many know you in the latter way as a collector as opposed to a photographer, but having seen your Facebook feed for some years now, I know you are as much an explorer as many of us are; in your element, with camera in hand, walking and shooting.

I appreciate that! I think this idea that one collects is somehow attributed to a vocation; a job as it were. As much as I wish it was my job to spend money to buy photos for my collection, sadly that is not the case. The ‘collector’ tag came early on due to my social media streams, but also my first book with Self Publish Be Happy in which I had made a mini-narrative from items in my collection about American and the Disneyfication thereof. I guess that was 2012.

I have been making photographs since roughly 1996, but in terms of adjusting this position to my ‘career’, I always found it limiting in so much as how most people who only have their “art” to barter with, for me it was to be self-involved and without any gifts other than their privilege to make art and share it. This is fundamentally why I am so involved in writing and reviewing; I want to have a function that overpasses simple “artist” status. I do not want to be arrested by the cancer of self-involvement.

So, although this is my first published book of photographs, there is quite a backlog, but I will admit freely that the book medium is now how I look at making work. I loathe exhibitions. I feel the book in itself is the form and that started around 2010, so although I have lots of work predating that, I am concentrating on making themed bodies of work that could fit between two covers. I also loosened up after the birth of my son and find that wandering in a specific location and responding to what is in front of me, like a more pitiable street photographer, opens up things that I wasn’t concerned with before which had a lot to do with staging photographs and of the body. Now, the lack of body in most of my work is the substitute for its involvement. What’s missing becomes what is.

All images and spreads Dein Kampf by Brad Feuerhelm, published by and courtesy of MACK, 2019