In Conversation – John Edmonds and Kameelah Janan Rasheed

John Edmonds (JE): Kameelah thank you so much for your willingness to talk with me. When Paper Journal approached me about having a conversation with another artist I knew I wanted it to be you. For a number of reasons I feel we share a lot despite our differences and I also wanted to speak with an artist I’m excited about. So I guess the first thing we could talk about is photography: Photography as a medium, as an act of resistance and preservation- and, Photography as material, per your work. So I guess the first question I would pose to you is: what is the role of photography in your own practice?

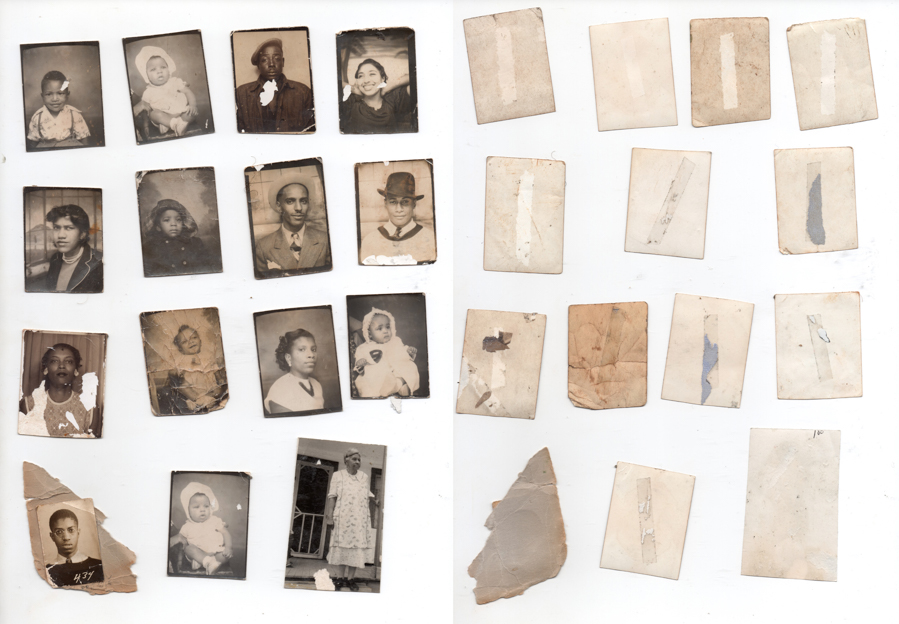

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (KR): The first photographs I encountered were family photographs. I was interested in their materiality; they were often folded, stuck to something else, or were covered in fingerprints, or even the occasion food stain. Obviously, someone had spent time with these photos, and these signs of engagement reminded me of the comfort with which someone felt in revisiting these images even in the middle of a meal. These were markers, witness marks. There is the photograph itself which has texture and meaning. There are also the witness marks which are another layer of meaning. This materiality, the gestures or indications of time, and even the metadata written on the back of photographs is what excites me about photography.

JE: Right. I think about photography and materiality; I personally came to making pictures out of an affinity for the printed image-magazines, family albums–photographs we see in their physicality. I was talking to a friend earlier about this: Most photographers born before 1985 came to photography from the place of thinking about the familial photograph. Right now, we are at this juncture where much of our generation are really influenced not only by the photographs that we see from familial albums that we can touch, but also photography that is mass produced and that has a connection to advertising that conjures desire and desirability. Of course, the advancing of technology has had a tremendous affect. Many of the men that I’ve photographed on a day to day basis, from meeting them in the street, get togethers or other places where you come together like a family, are looked at sort of like an extended family or extended community. I always feel like I’ve known them, in some way, shape or form, in the universe. I collect people through picture making. When I made my most recent series DU-RAGS, I printed the images on silk. The impetus behind that decision was to give the same sense of experience in seeing men and women wearing du-rags in Crown Heights. When I first moved here, I would always see the trains of these Du-Rags just moving in the air, never seeing the face of the individual. I wanted the works to replicate that same type of nuance, I wanted to provide the viewer with that same sense of beauty and sensuality.

The role of beauty is something intrinsic for both of us in our practices, from different angles–the subjectivity of experience and narrative. I think this is something that we share. One of the things I was thinking about when defining what topics we could address is that for us both, there is definitely the personal that is at the root of everything. And the personal is political. For example, Black feminism beginning this notion about the personal being political. How do you see that in your own practice?

KR: I often think about surveillance, particularly within the context of Simone Browne’s book, Dark Matters. There is so much of black life (and death) that is surveilled by the state, and this being a normalised relationship, I have grown interested in the strategies of maintaining privacy, asserting an interiority, and resisting legibility. What do we get to hold as “personal”? These ideas of opaqueness, selective legibility, intentionally hiding information to make it only legible or understandable to selected audiences is a context of survival I grew up in. My mother never explicitly framed anything like a black feminist tradition because I don’t think that language needed to be used. There was, however, clarity around how to strategically engage with my public and the necessity of presenting yourself in a particular way to be safe, or as safe as is allowable under the conditions.

We had a publishing center at my school when I was in second grade. At lunchtime, you could bring your handwritten stories and the older woman there would type them up for you. I would come back a day later to select paper and binding. Before I completed second grade, I published and illustrated over a dozen books. My parents encouraged my literary pursuits, attending all my book talks and including my books in our modest home library. My parents more than anything was invested in ensuring that I was telling my own stories and could make sense of the stories other people were telling me. There was a commitment to critical literacy, critical consumption, and critical production.

When I think about black feminist traditions, I like when labels are put on things, it does help to figure out, to pull apart what’s happening. But there are also things that are intrinsic in the way that at least my black mother mothered me, that refuse a clear label.

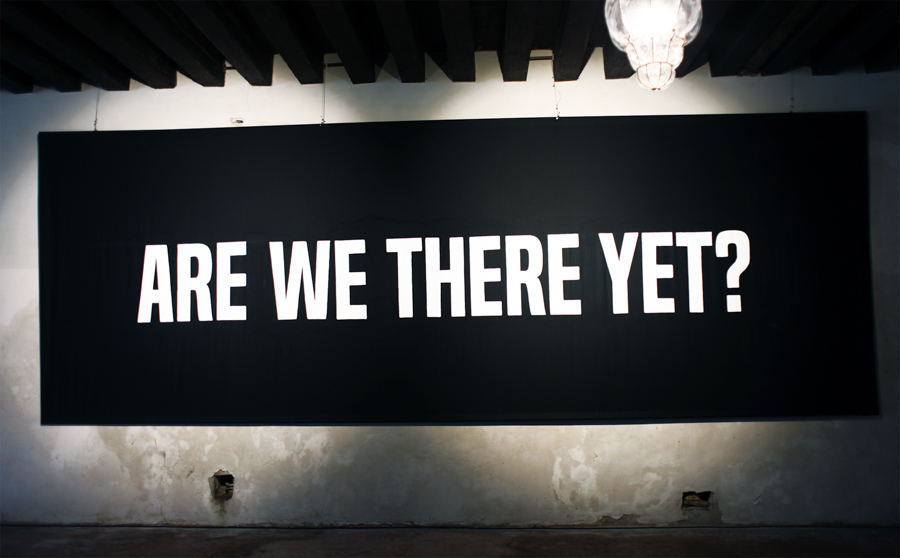

JE: On the topic of both telling our own narratives and visibility, I feel like that has been such an intrinsic survival strategy for Black people in America. I like what you said about the idea of language, how we label and identify things as movements or strategies–but how at the root of it all, we have been using these strategies of making narratives visible and storytelling as a form of survival since forever. The other thing I’d like to talk about, which relates to survival and visibility, is how you use text with images, or even text as image, specifically in your series Lower The Pitch of Your Suffering. When I look at this particular series there’s this way of speaking, a voice that has both humor and authority. I love that you’re able to voice yourself through text and tone of voice. Could you talk more about that work and it all came about?

KR: I started How to Suffer Politely (and Other Etiquette) in 2014 as an immediate response to United States police officers killing Black people and being acquitted. I was watching all of the news stories, and everyone seemed to be more focused on issues around respectability, protection of property, not being inconvenienced by the articulation of Black suffering through street protests and other uprisings. There was an unsettling, yet familiar policing of effect – or response to routinised trauma. I was fascinated by that, particularly, the turn in language. I know that the murders were violent and hurtful, but there was also this other fascinating thing that was happening which is also violent, which is to tell an entire community of people to find a way to package our suffering in a way that’s palatable and makes someone else feel comfortable. I was fascinated by whose comfort was prioritised. I was fascinated by this idea of etiquette and politeness. Even during the Reconstruction era after slavery, kids going into black schools, and being given readers that instructed them on how to conduct themselves in a “post-slavery society.” What this means is that the major concern is not the structural correction of injustices or the radical redesign of society, but how Black people can engage in some emotional acrobats to make everyone else feel comfortable. All this emotional labour in “post-slavery” society being spent, still, on fulfilling someone else.

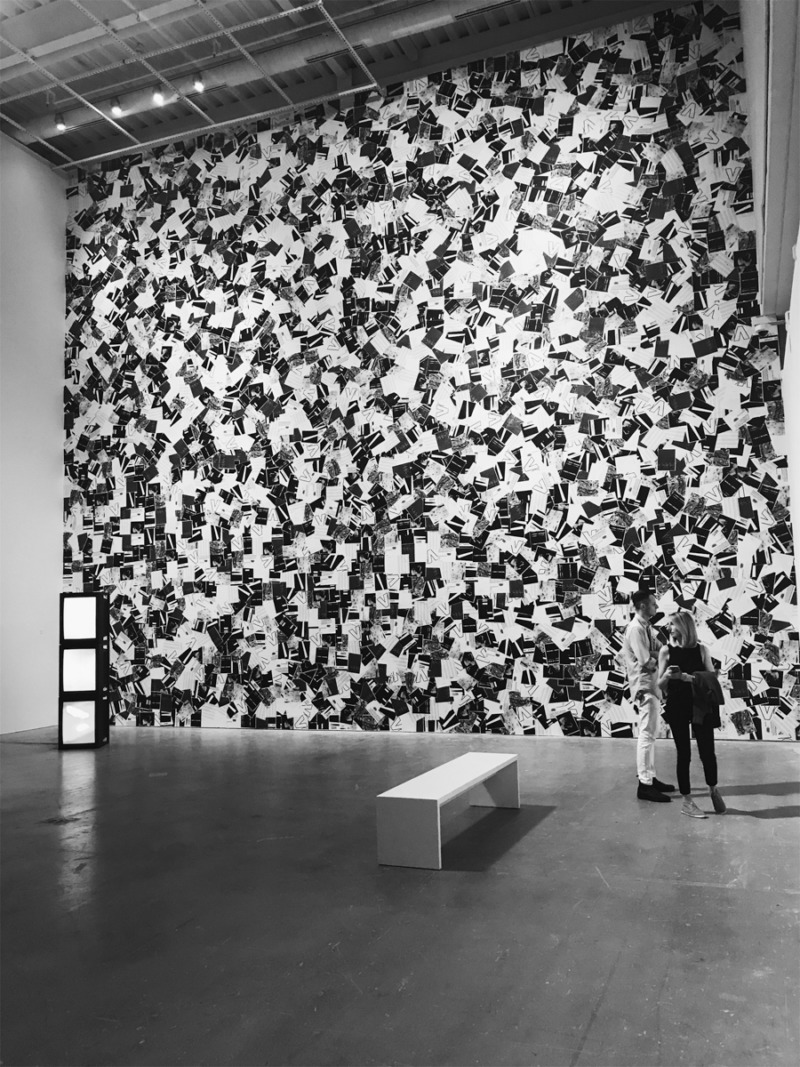

This series came out of a way of me thinking about a lot of things because to language, relative comfort, and emotional comfort. When police were (and are) murdering Black people because mainstream news fodder, I was almost compulsively reading these think pieces and sometimes the comments-sort of mining them to identify threads. I was really thinking how do I compress all the activity which I’ve been reading, how do I compress all the books I read in college, how do I compress all my experiences into something that is quick and fast, and easily readable, easily digestible and can be put in public spaces? And in those public spaces, people can engage with it passively and actively. So I sat down in wrote these short poetic gestures and placed them on this yellow background which I now call “caution yellow” and began sharing them. The series started becoming a bit more popular and started being installed in public spaces, and I liked the way it was being installed because it was almost a situation that you couldn’t not see this, as they’re 10 feet tall. You can pretend that you walk by and not let it catch your attention. It was also a confrontation. I liked the idea of taking up space. Having worked on a substantially smaller scale, it’s great to take up space and to see your work 10 feet tall from NYC to Glasgow. I think with language it’s key to recognise what language is appropriate to certain circumstances. Harryette Mullen who is one of my favourite poets, does a lot of work around considering advertising language as meaningful influence for the structure of some of her poetry; I feel I work a lot in the same ways of thinking about how I place these messages in the same spaces that they would exist as advertisements, because people are always going to look at advertisements so if they look at the advertisements, they may as well look at this too.

I know that the murders were violent and hurtful, but there was also this other fascinating thing that was happening which is also violent, which is to tell an entire community of people to find a way to package our suffering in a way that’s palatable and makes someone else feel comfortable. I was fascinated by whose comfort was prioritised.

JE: There was a similar trajectory when I made the Hoods pictures. I photographed a very specific article of clothing from my wardrobe, coding the subject as myself or as how I may look in public space. The hood is a gendered and racialized item of clothing. I used the hood to raise questions about assumptions. I put one of the images from the Hoods series on a billboard, subversively. We usually see billboards used for advertising purposes, not political messages. Unless, it’s propaganda.

This could be my own desire to find similarity between us because of my admiration for you and your practice, but I also feel there is a significant use of tone with both our works. There is a quietness to the Hoods pictures; a simplicity and minimalism. They are quiet, but always monumental in scale. I’m saying it plain and loud: a tradition in a lot of Black power and other Black revolution movements.

KR: Yeah, I think it’s like this other thing of being able to switch registers too–being able to play with tonality and registers to create a moment of productive discomfort and confusion. Those moments of misreading where an audience doesn’t know if you’re sarcastic or you’re serious. Some people have said, “how dare you tell them to lower the pitch of their suffering.” This moment invites dialogue. I appreciate the feedback loop because it allows me to consider the permutations of how the work itself is read. This feedback loop helps me think about the next steps in my practice and the ways my work can operate at different registers.

JE: That’s a really interesting point. I was thinking about it just in terms of working with material that is very personal. For you, when does the personal become political? Is there a threshold? Is the personal always political? Or is there a certain moment that work enters into a public sphere of a dialogue? These are questions I’ve been asking myself about lately.

KR: I would have to think through each project. If I were to speak generally, my work goes from personal to political, rather; it operates in both spaces simultaneously when I decide to make the work public and available for activation. I’m still struggling with the idea of what is political art because it seems that when something is labelled as such, it forecloses most conversations about materiality, or scale, or texture, which in addition to its social commentary are also important features. For example, you chose silk for a reason; you didn’t just wake up one morning and say, I want to use silk. Coming back to this question, my work enters that threshold into art and occupying the space of the political when I want to think publicly about what I’m processing or when I want others to think alongside me. I think it is important to think publicly and collaboratively.

JE: I love this idea of thinking privately versus thinking publicly. So it’s not only when the when the work is shown publicly, but it’s actually when you want to make something visible for other people to process and actually think along with you. I love that. It brings us to my next question which is more personal. I always look at your online presence, how dynamic your own process is. I’ve always been so interested in how you just seem so in your zone, I don’t want to call it reclusive or closed off, but there’s something about your personality that is like “I’m always working even when I’m not sharing.” That’s one thing I really love and respect about my favourite artists, that the work is not only the work you do, it’s also what you go through to make it, how to distil those experiences in the work that you make. So in thinking about the role of solitude in visual art, something that all artists have to deal with, dealing with being alone, living with your work, in having a relationship with your work being close to you. How does the role of solitude play into your own practice?

KR: I have always worked since the age of thirteen. At thirteen, I worked as a web designer for a local teen web design company and a teacher’s aide for summer school programs. By the time I was sixteen, I’d just finished high school and was wrapping up my third year as a teacher’s assistant. And throughout college, I worked anywhere from two to four jobs. The setup of my life is that I’ve always had financial responsibilities and as such, I am very deliberate and intentional about my time. I always wanted to be a high school teacher and I did that for several years. Six formally and about four in prior years in auxiliary positions. I came to art after I had, and while I was still in another career. I was a high school teacher working 60-80 hours a week while making art. Even now, even though I am not in the classroom, I work as a curriculum developer and am still working up to 60 hours a week, sometimes more, then I come home to make my art. My mind I always go back to Maxine Waters who’s like “I’m reclaiming my time.” Maxine always says all the things we’re thinking, and for me, it’s kind of like I don’t have time to play around with my time. I get up at 5, make my prayers, send emails, make some art, got to work, leave work, and I’m at my studio until I am done. Then, I’m getting up and doing it again. I don’t have time to play, and the way I think my own spiritual practice also is that I need to be accountable to the question: “did you use your day wisely?”. I’m very vigilant about my time. I’m very vigilant about what it means to rest. I’m very vigilant about what it means to engage even in my friendships, and those friendships with people who are also working hard. And marrying someone who works just as hard as me and understands what it looks like to want something and to work for that! I don’t know how long my time is here in this Dunya, or this earth-this world, but I know I am not going to waste it frivolously to the best of my abilities. I’m very much always focused and when I go to bed at night asking myself “have I done all that I could?”, “Is Allah pleased with my offering?” “have I put something into the world that I think is of value to other people, like my ancestors?” I want to be aligned in that way. As I tell people, I socialise in batches. You’ll catch me at events several nights for one week, and then I am hibernating for up to eight weeks because there is no way to be at every opening and still have time to work. Especially, in my case, if I am working from 8-5 or 6 every day, my evenings become increasingly more precious. I need to be strategic.

So when I think about solitude, when I first moved to New York City because I didn’t come to art from art school, from any art background, it was very lonely for me. I was trying to talk to people about art, but I didn’t have networks, I didn’t have an MFA, I didn’t have the credentials. In response, I spent a lot of time reading and tinkering, reading and tinkering and making bad work and trying to make better work. I ended up learning how to be my best feedback loop. Of course, I ask friends, and now even my husband for feedback, but I think solitude has helped me be more strategic and in tune with the details I produce. It has made me love and trust myself more, which is important. So I think solitude is important, it’s necessary. I think it’s important to be alone with your thoughts. I think it’s important to be uncomfortable, from discomfort. The things that I think when I’m by myself, I would never think about that when I’m sitting in a room with someone else or in crowded social setting.

JE: For me it’s very similar, we all need to deal with ourselves. The fact of the matter is that art is a process of learning and unlearning, a process of decolonizing, trying to remove the facade to get closer to something that’s more real.

And how we get closer to what is real is so different from one artist to the next. I really identify with what you said about spirituality; I grew up in a Baptist family and there many things I identify with in religious practices, despite not considering myself religious. Much of what I learned in going to Church, like faith and trusting the journey, I’ve learned to apply to what I am doing in my own work. Spirituality is learning to be with yourself, with your thoughts and actually trying to be this whole as you can.

I appreciate your generosity, your openness and your willingness to share your thought process with others, because for a visual artists we are always distilling and re-figuring things out. I feel that showing that process, letting that hand show, is encouraging others to be vulnerable and open. I feel that it’s just so generous and I want to thank you for that.

The hood is a gendered and racialized item of clothing. I used the hood to raise questions about assumptions. I put one of the images from the Hoods series on a billboard, subversively. We usually see billboards used for advertising purposes, not political messages. Unless, it’s propaganda.

KR: I think that’s how my brain works. Also, when people ask “can I buy that thing?”, I think “what stage of that thing?”. In my mind I’m constantly iterating, I’ll make something, and I’ll keep iterating and iterating. I do believe, as a former high school teacher, that of course I love for my kids to get a good grade and learn a particular thing, but the process of learning something is the most beautiful, spiritually enlightening process you can ever engage in. Starting from the point of curiosity and testing out different neural pathways to understanding (or even approximate to understanding) something where the goal isn’t necessarily to answer a question, but also understand why you’re thinking that way, and the thousands of other permutations for thinking is exhilarating. It’s like a beautiful experience to watch a 14-year-old kid from Crown Heights who has been told in many contexts across many years sit and think: the fidgeting, the tilted back head, the scribbles, that moment where they think they’ve grasped something. I would be a dishonest artist if I only made a thing to here. I want it to be a thing, or a series of things, or an ecosystem of things with which people can grapple. I think honesty and generosity in work are important. I think you should be honest.

JE: I think so, too. When we are honest, we’re good. Although sometimes it’s hard to tell the full truth. Both in how we got to a certain point and where we are in a conversation that may be relevant to our practices.

So my last question: Who are some of your favourite artists and writers, the ones you are thinking about or that you always revisit?

KR: Yeah. I think people would get annoyed because I usually answer this question with a list of writers because my practice is so deeply influenced by language, text, and sonic utterances. I love Harryette Mullen. She’s an amazing and reclusive poet who has mastered the art of “reclaiming [her] time.” Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah is a great essayist working in the long form as an assertive reminder that Black lives and histories are indeed worthy of elaboration and of taking up space. I admire the simplicity and architectural gestures in Leslie Hewitt’s work. Beverly Buchanan’s work at Brooklyn Museum this year was so refreshing and subversive in its interdisciplinary roots. I think one thing that unites all of them is that going back to Maxine Waters, they all reclaim their time and they are strategically engaged with the public. They come out when they want to come out. Otherwise, they are working or resting to gear up for the next iteration of their practice. I think these artists and writers are also important to me because of their nuance and rigor. In Mullen’s work, there are layers of referential details and turns in language that make you work. Ghansah’s writing often reminds me of a well-researched and meticulously referenced epic. I know it will be a long, but enriching ride. I know that I will need to find an ink cartridge because I will want to print it out and annotate. Her work compels rigor and attention to detail. I remember seeing Hewitt’s early works and for the first time encountering Buchanan’s work. In both instances, there were all these lovely details that drew me closer to the objects in ways that reminded me of the importance of durational observation. And of course, my peers, but that is a much longer conversation because there are so many great ones! What about you? Who are your favorite artists and writers?

JE: When I was 21, a man I was seeing at that time gave me a book by E. Lynn Harris. Harris passed in 2009, but he was and still is very well known for his first books that unveil this lifestyle of Black men living on the “down low” and what it means to have a double life. I still think that he is under appreciated. He sold his first novels out of his car trunk- I find that amazing. It means he decided to himself “I’m going to get this out here in anyway I can” and that’s powerful to me. When you really see necessity, like I’m going to do this because there’s a need, it’s very powerful. I love James Baldwin, too, obviously, Susan Sontag. As far as contemporary writers, Hilton Als, Teju Cole & Helen Oyeyemi, just to know a few. As far as visual artists go, I’m always looking at my peers that stick to their vision, and the work rigorously–who are dedicated to getting the work done, by any means necessary.

John Edmonds is an artist working in photography who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He received his MFA in Photography from Yale University School of Art and his BFA in Photography at the Corcoran School of Arts + Design. He is most recognized for his projects where he focused on the performative gestures and self-fashioning of young black men on the streets of America, as well as his evocative portraits of lovers, close friends and strangers. He has held residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine; Light Work, Syracuse, New York; FABRICA: The United Colors of Benneton’s Research Center, Treviso, Italy; & The Center for Photography at Woodstock, Woodstock, New York.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (b.1985) is a Brooklyn-based interdisciplinary artist, writer, and former high school public school teacher from East Palo Alto, CA. Through installation works that combine photography, printmaking, publications, poetry, and performance, Rasheed’s research and work examine language as it relates to constructions of Black subjectivity. Rasheed’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Her work has been presented at the 2017 Venice Biennale, Institute of Contemporary Art – Philadelphia, Printed Matter, Jack Shainman Gallery, Studio Museum in Harlem, Bronx Museum, Queens Museum, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Pinchuk Art Centre, and others. Her work has been written about Artforum, Guernica Magazine, The New York Times, Art 21, Wall Street Journal, and ArtSlant. Recently shortlisted for the Future Generation Art Prize in 2017, she is the recipient of several other awards and honors including the Denniston Hill Artist Residency (2017), The Laundromat Project Alumni Award for Art in Community (2017), Harpo Foundation Grant (2016), Magnum Foundation Grant (2016), Creative Exchange Lab at the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art Residency (2016), Smack Mellon Studio Residency (2016), Triple Canopy Commission at New York Public Library Labs (2015), Lower East Side Printshop Keyholder Residency (2015), A.I.R. Gallery Fellowship (2015), Queens Museum Jerome Emerging Artist Fellowship (2015), New York Artadia Grant (2015), Bronx AIM Fellowship (2015), Process Space Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Residency (2015), Art Matters Grant (2014), Rema Hort Mann Foundation Grant (2014), Center for Book Arts Residency (2013), The Laundromat Project Create Change Fellowship (2013), Center for Photography at Woodstock Residency (2012), among others. A 2006 Amy Biehl Fulbright Scholar to South Africa, she holds a BA in Public Policy and Africana Studies from Pomona College (2006) and an EdM in Secondary Education from Stanford University (2008). She is on the faculty of the MFA Fine Arts program at the School of Visual Arts and also works full-time as a social studies curriculum developer for New York public schools.