Interview – Paul Knight: jump into bed with me

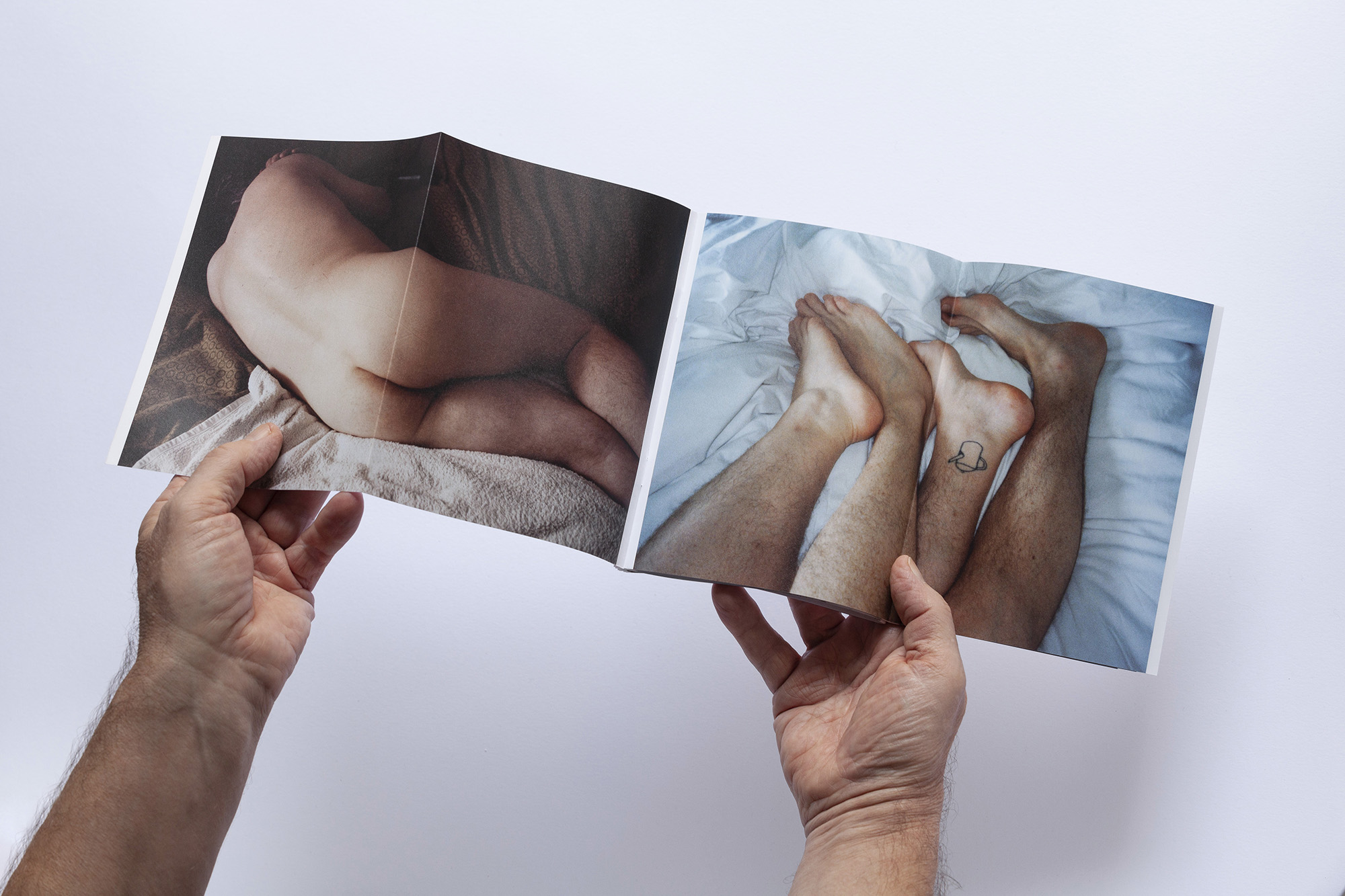

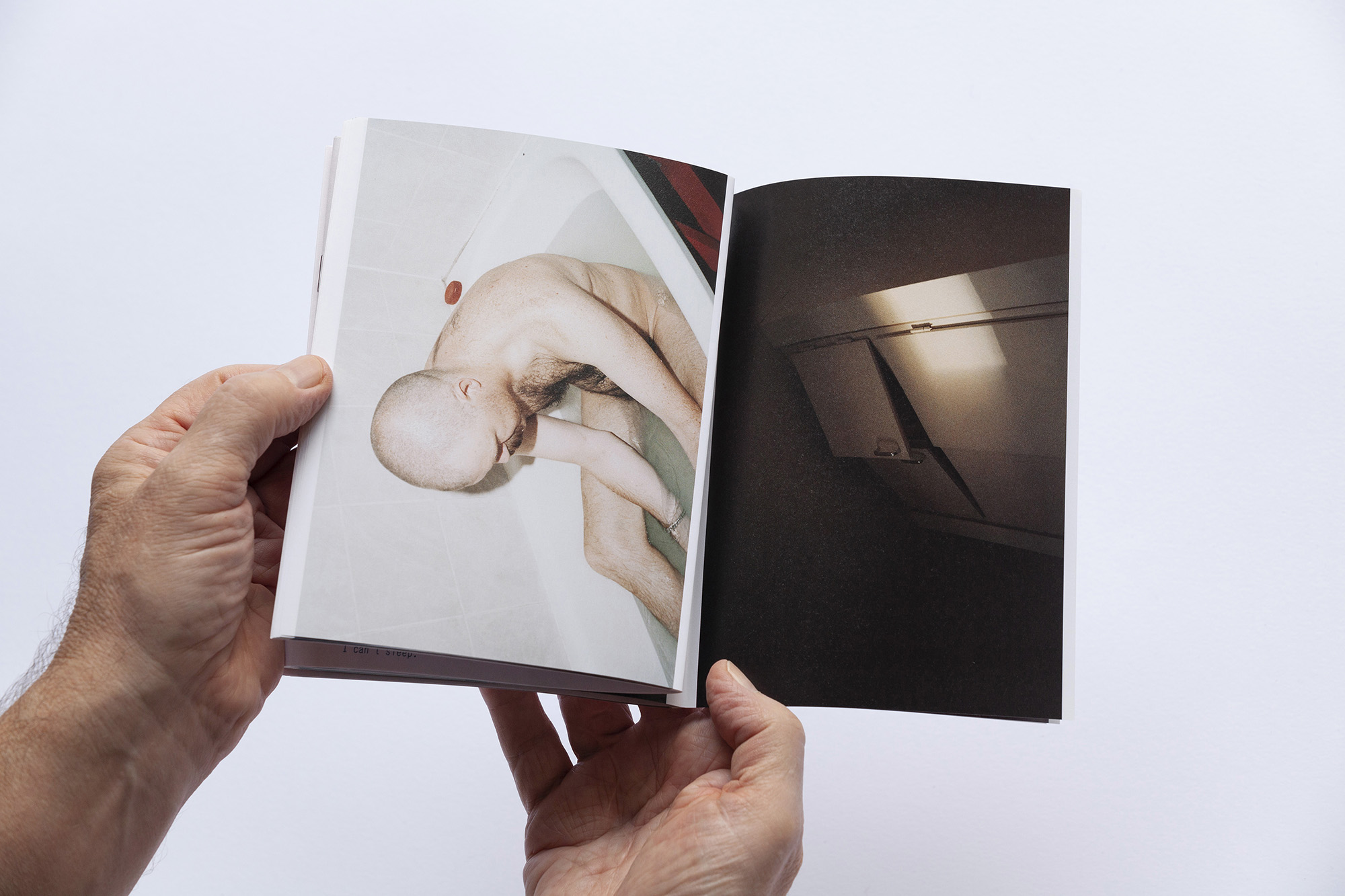

Consisting of photographs taken from long-term project Chamber Music, comes jump into bed with me, the first book from Australian-born, Berlin-based photographer and artist Paul Knight. A modern-day love letter between Paul and his partner Peter, the photographs reveal intimacy in all of its guises; the candid, the mundane, the erotic.

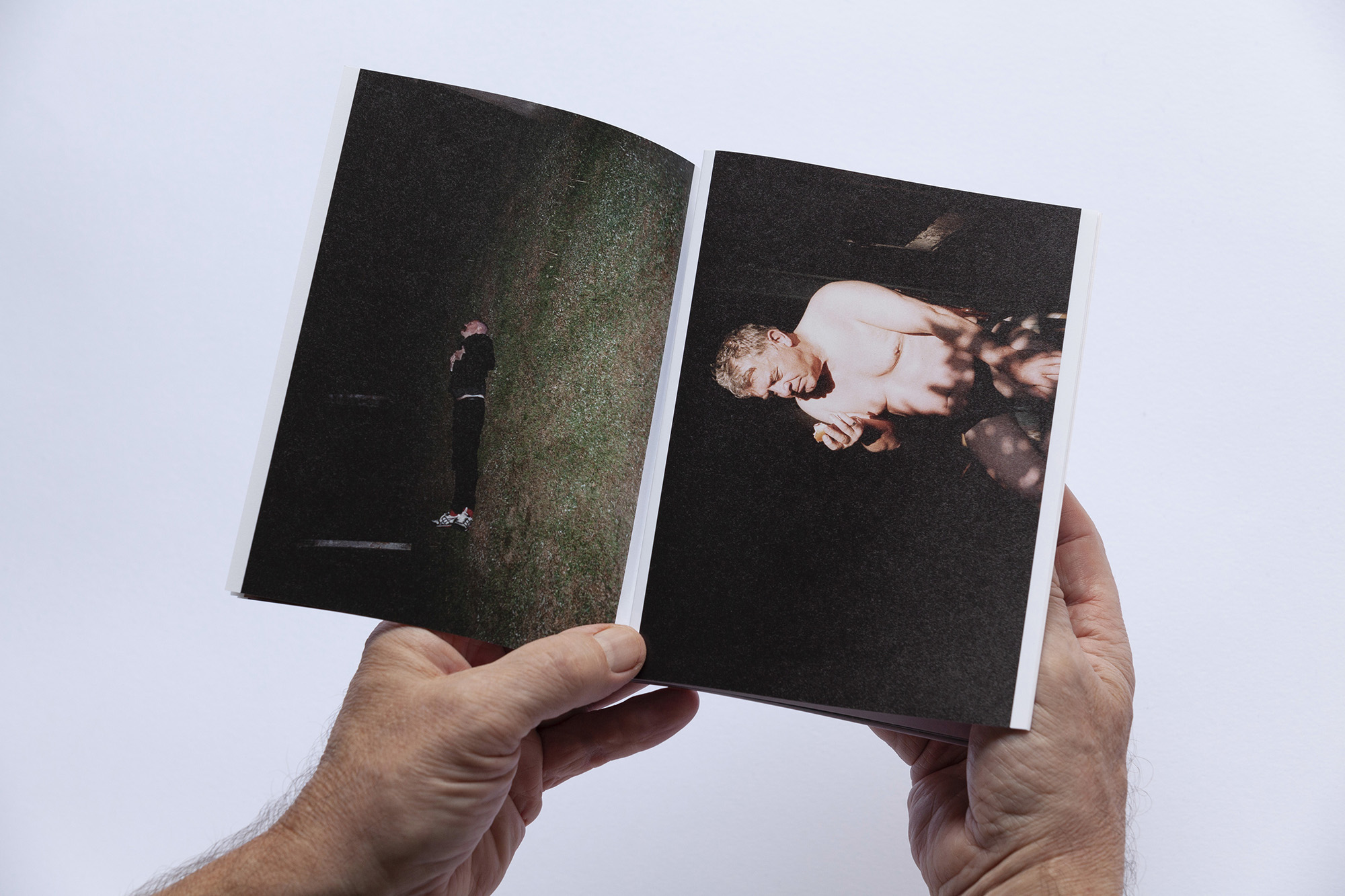

With the camera moving fluidly between both Paul and Peter, and using any available surface to place the camera and setting a self-timer, the camera invites a new level of vulnerability from its subjects. “My interest in power in the image is when a subject lets go of power”, states Paul. “In this way, the vulnerability you see is a very important part of the work.”

Published by Perimeter Editions and recently awarded with a Commendation in the Australian and New Zealand Photobook Award, we spoke to Paul about sharing such a personal body of work, the relationship between the camera and its performative space, and the importance of using text to introduce a new layer to the body of work.

Sometimes people will make comments or assumptions that they know myself or Peter or even ‘how we are’ as a couple because they’ve seen the work. I find this really curious, that people blindly trust the image as if there are no steps between us and it – as though it’s not intrinsically a performative space.

jump into bed with me is very much a modern-day love letter. Intimacy is laid bare and all versions of the every day is on display. The vulnerability, yet total candidness shared between yourself, your partner Peter, and the viewer, is the first thing that struck me. How does it feel, to share something so personal?

The relationship of the image to intimacy has been a constant interest to me. I have developed the perspective that an image is an independent object which engages with people, society, etc. from a position of its own agency.

Themes relating to aspects of power like violence, sex and social economics, thrive in and activate the dynamics of the image comfortably. However, our social and individual obsession with embraced forms of power is something to lament; I am not interested in power harnessed for individualistic gain. My interest in power in the image is when a subject lets go of power. In this way, the vulnerability you see is a very important part of the work.

This acceptance in the act of opening ourselves to the camera doesn’t mean it comes without reservations and pain at times; both Peter and I have issues with our bodies and perspectives that are challenged for us personally by making the work. But we experience an extreme bond and I’m always interested to see how much the camera can actually see and reproduce; this requires an ever-expanding giving on our behalf to continually test that.

The intensity experienced when we first met, indicated to me that our connection was worth photographing and it was in those first few months that the perspective on how to formulate a system in letting the camera attain a primary position was developed deeper. The very first day we met is partly depicted in the two images at the back of the book – the images of our naked bodies with the tomatoes and cheese. These images sum up a fundamental attitude from the outset in the making the work – that we are in essence food for the camera and that the camera is highest in the idea of order in a food chain.

For all of my hardness in how I think structurally about the work, I can still look at certain images and become quite emotional. There is a benefit for us in the risk we take in producing this work. An archive of our lives exists in the photographic space because of this work.

The photographs were mostly taken by placing your camera on an available surface and using a timer. We see snippets of your life together – dirty dishes, unmade bed, fruit still life; but the main focus is on your physical relationship with Peter; we see you together at the beach; making love in a field; embracing in the shower. The camera becomes the third eye in your relationship; we see what it sees, and it invites a type of voyeurism. I’m interested to hear your thoughts on the performative nature of the photographs?

There is a particular relationship that we both shared towards the camera in the making of this work. The camera has always been offered a sense of its’ own agency. The camera would pass between us; sometimes we look in the viewfinder, sometimes we don’t. Sometimes the camera is triggered by a self-timer propped up on whatever support is close by; a chair, desk, cliff-face, or tree. In this looseness of ‘me’ enforcing myself less on the machine, it has a chance of being freer in a sense to be what it is and see how it sees.

Some of the scenes of vulnerability and intimacy you see in the work are constructions and some are from true moments; this aspect of confusion or not knowing plays with the indexical question that is entangled with the image. I find a more accurate way of thinking about the question of the closeness of the image, is that it is not from us but more that it sits parallel to us; it sees us and then creates a new space, reflected.

We look at each other across the gap; us and the image. The camera, when given agency, evokes this relationship more; I want to foster that. This third perspective can’t help but be performative; these ideas are tethered, as we are to it but there’s always a distance there. It’s this thought of the image operating parallel – similar in how a mirror is a performative space – that I understand our performance is with the camera-machine and not the audience. I think that idea frees us to be more giving to that space.

Sometimes people will make comments or assumptions that they know myself or Peter or even ‘how we are’ as a couple because they’ve seen the work. I find this really curious, that people blindly trust the image as if there are no steps between us and it – as though it’s not intrinsically a performative space. The work, in a reductive way, is about something that we all share, external to gender, culture and commerce; it is the idea of a universal silhouette, which essentially is being, and the gentleness that can be in being; but even being becomes performative in the photograph.

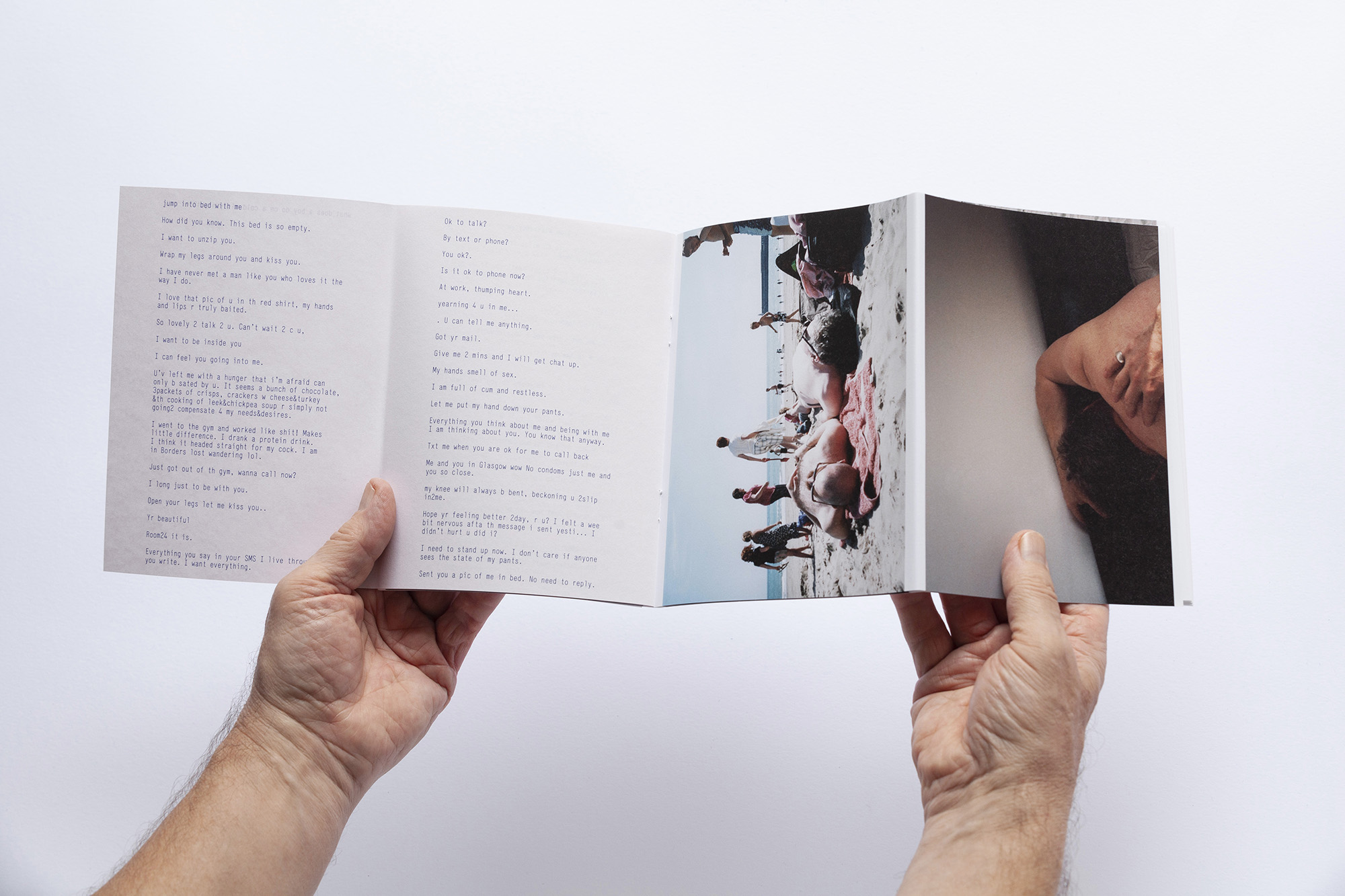

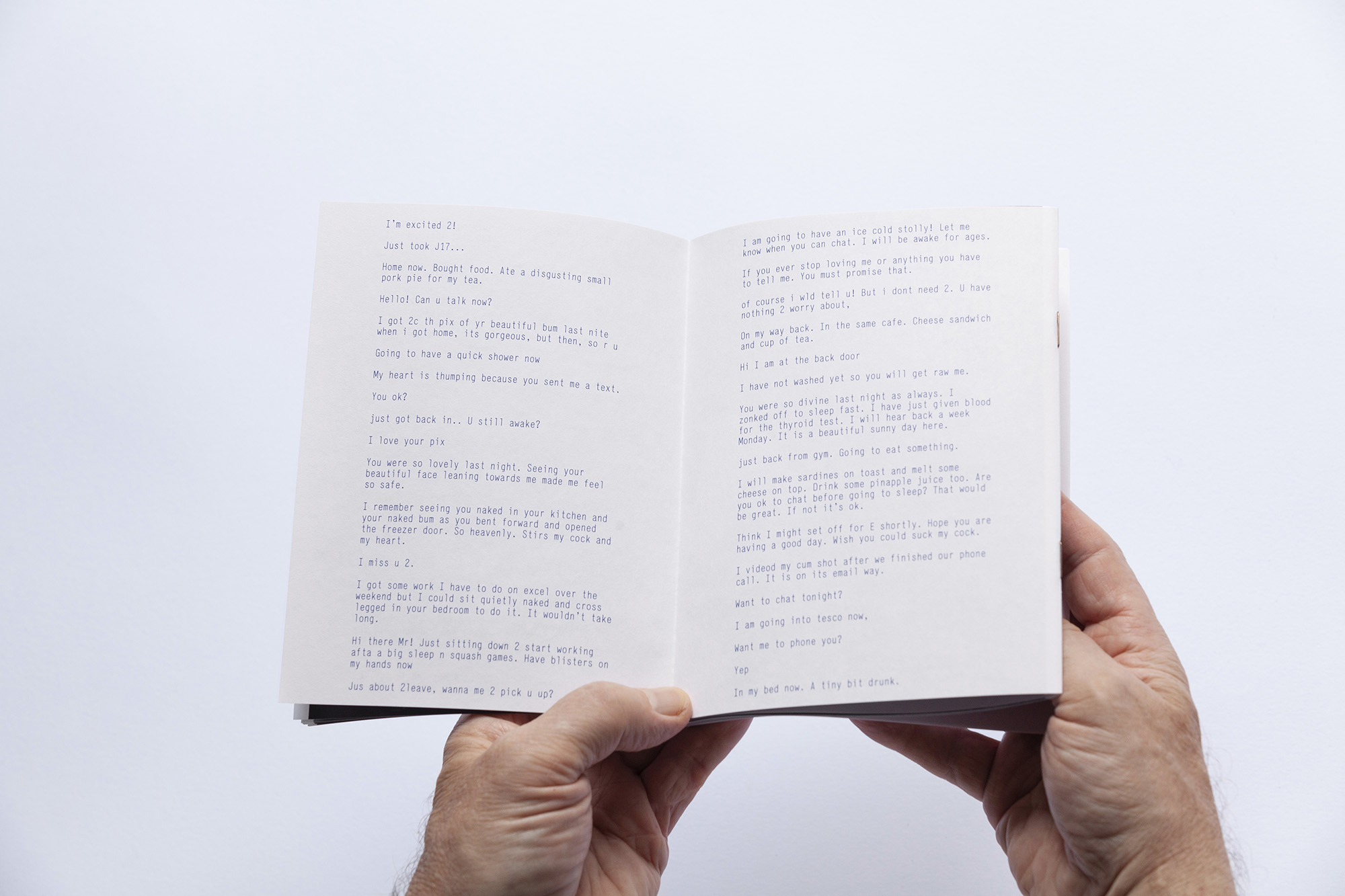

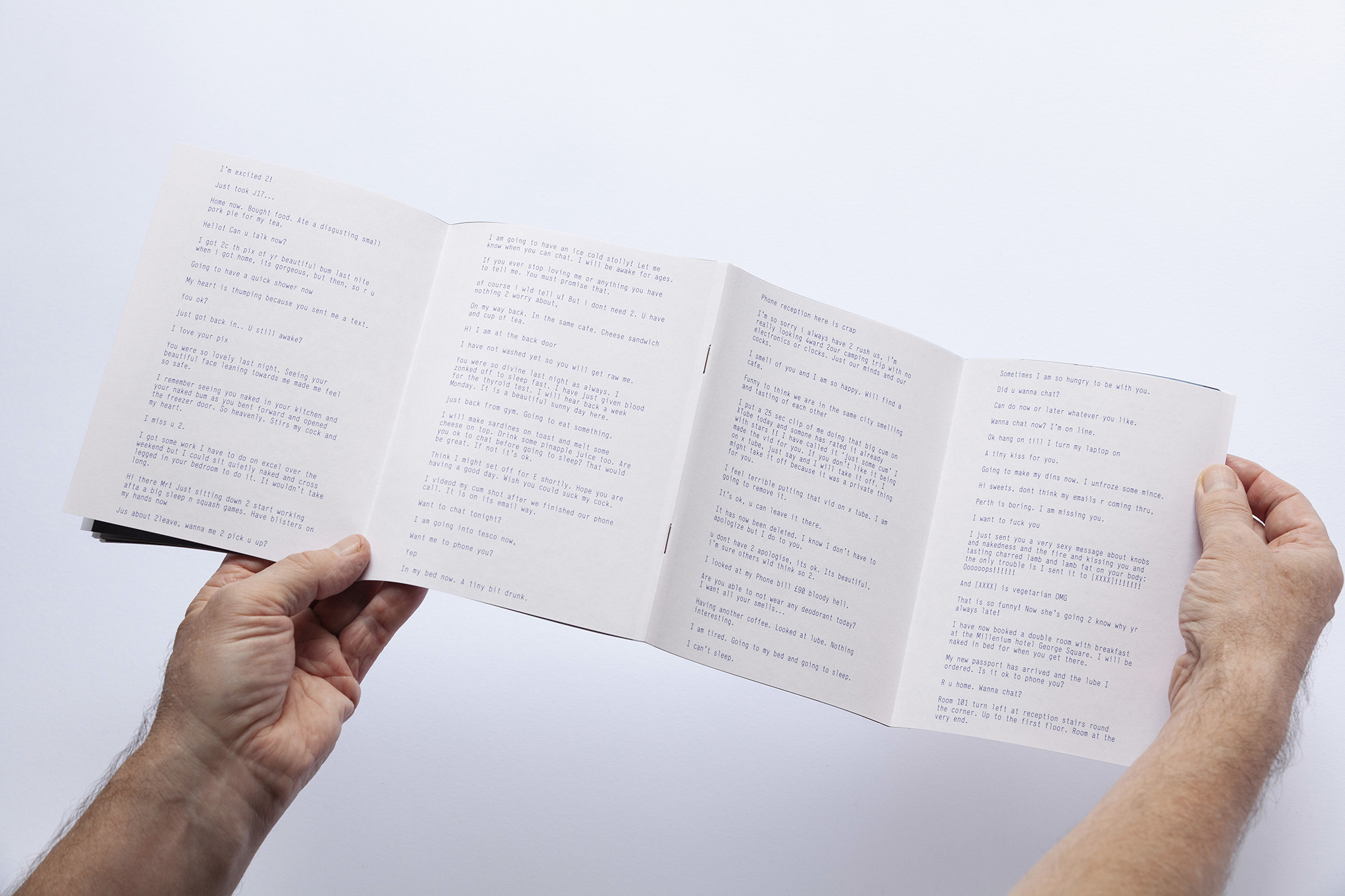

Throughout the book are text message exchanges between yourself and Peter; like the images, some are mundane, some erotic, but also some are deeply personal. Why was it important for you to include these?

In dealing with the work in book form, we questioned how intimate can this object be? When someone holds this book in their hand, how much are they holding, how much can they feel?

The work into book form really was a long process, the work from Roland Brauchli (designer) and Emma Capps (editor) was very deep and involved. My hope is that the book feels casual, gentle and effortless in spite of the fact that it demanded a lot of energy. I had kept the text messages as they seemed to function in many ways similar to the image, so my interest was spiked in them from the start of my relationship with Peter as well.

There was a moment when their inclusion was obvious. Both the images and text-messages approach a shared subject matter from very different positions; they over-lap yet evoke qualities unique into themselves. The edit of the images and text-messages both loopback unto themselves but when next to each other in the book, the feedback between them is quite high; shadows of texts read overlap with images they’re not printed next to and vice versa with the images. This interaction felt more akin to the slippages we experience with memory.

One thing I was sure of was that I did not want an essay in the book explaining the work or why people should value it. I wanted people to encounter the book unexplained – I wanted the book to have its own aspect of risk. It doesn’t bother me if some people don’t value it; many won’t. The book demands a certain type of resolve in the approach of the person who holds it, you have to take part and give it something for it to have its meaning, maybe even putting something to one side.

The book is a bit unassuming, as an object it’s also very vulnerable and can be easily dismissed. Using the text-messages in the book was much harder personally for both Peter and I than the images. I understand theories of images and how, as a society, there are formed positions of how they are dealt with. These text-messages, though, felt so raw and in many cases, they demanded so much work to keep them true to themselves. Text can have a finality that’s not always questioned; this pre-empting the notion of finality, took a lot of effort. The edit was worked down from over 100,000 words to around 4,000 and in the same way as the images, chronology, time and location were pulled apart and rebuilt.

I love the concertina format of the book and how it presents multiple layers and stories. Is this how you first envisioned the project to be presented?

When I’ve exhibited prints from the work, I always make sure that I break any sense of chronology in the presentation. I want the work in its’ collective form to maintain that it is a depiction of volume, a conceptual space or three-dimensional object, which sits behind the space of the print field. The work isn’t meant to read as a linear story, with a beginning, a middle, and an end; life, and how memory functions, feel much more complex than that.

I wanted to maintain the sense of a dimensional and interconnected-space within the book, that the edit was open to the viewer and the ability for it to change somehow. The photobook can be such a static, fixed and defined object; I wanted something more vulnerable and gentler, perhaps expanding.

The how-to was Roland’s insight and talent. We talked a lot about the scale of the book and the relationship to the hand, a scale that made the work feel special or attainable to the reader. When Roland sent me the first dummy with that concertina format, I knew straight away it was the right resolution to hold the work but which also allowed it to be as loose as it can be.

All images and spreads jump into bed with me, Paul Knight (Perimeter Editions, 2019), from the series Chamber Music, courtesy the artist and Neon Parc. jump into bed with me is available to purchase here.

View jump into bed with me in full on the Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award site.