Interview: Sebastian Collett

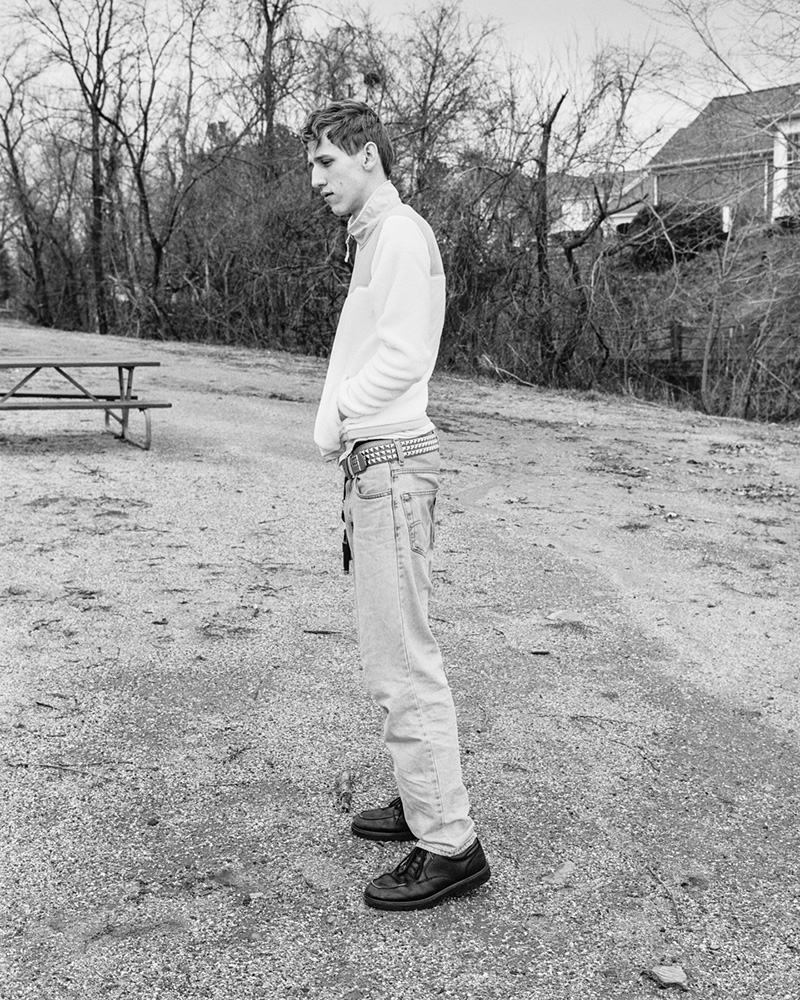

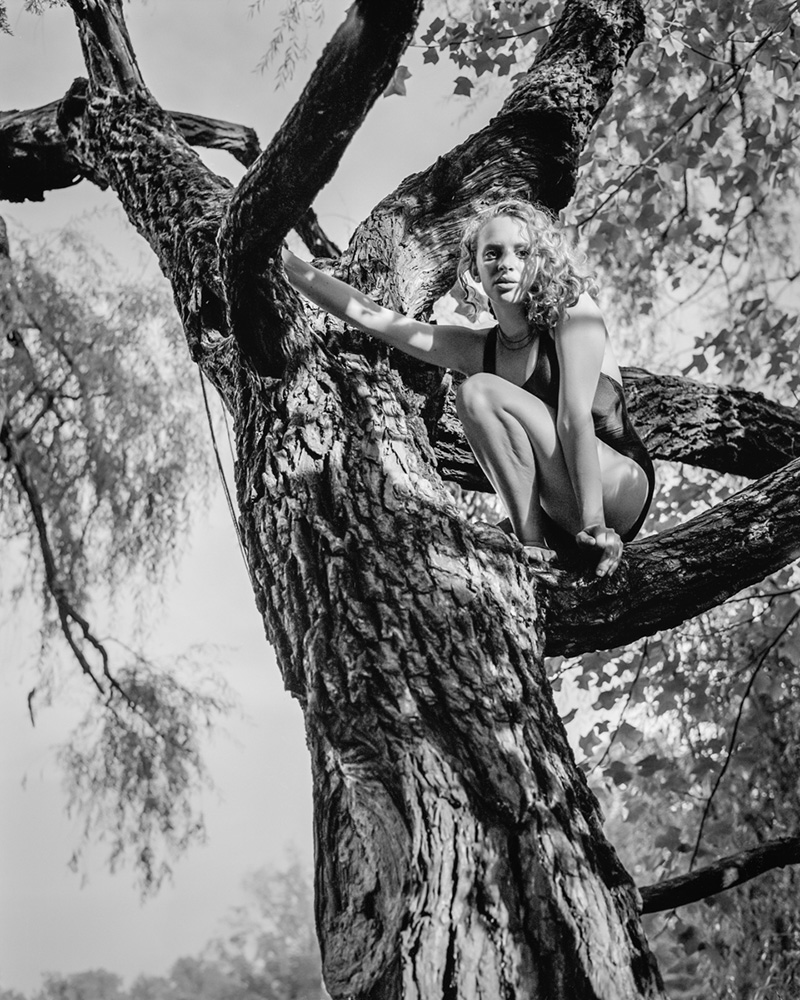

Sebastian Collett’s images are, at first glance, easily recognisable. Not necessarily by their exact make-up or by recognising the individuals he has photographed, but by the immediately identifiable feeling of adolescence. The images are quite clearly American—a sentiment expressed not only for the kid dressed in full gridiron gear—yet the feelings they inspire are perhaps universal, evoking experiences that we all have gone through in that awkward build-up to being an adult.

James Brown: You’ve mentioned that you were inspired to go back and create Vanishing Point after traveling home for a high school reunion. You spoke of feeling as though things had come full circle. The people that you have photographed are of a very diverse range of ages and it feels as though you’ve documented all the states that your life was in while in this place, and also things that could have been had you stayed. Do you think that’s a fair perception?

Sebastian Collett: Yes, in my project statement I describe it this way: “Immersed in the landscape of my youth, I scouted for “stand-ins” for characters from my past. Archetypal figures appeared: those I had wanted, or wanted to be, and those I was afraid to become. In their eyes, I encountered my alternate selves. Meeting my gaze, they foresaw their own ageing with a mixture of curiosity and trepidation.” Returning to one’s hometown, it’s a common experience to revert to an earlier sense of oneself. Retracing those old familiar paths, it felt like I was walking backward in time. More precisely, my inner teenager was resurfacing, so it was like existing in several time periods at once. When I encountered college students in their early twenties, I was seeing them from the perspective of my teenage self and I felt awestruck and intimidated, just as I had in high school. At the same time, I was looking back on their stage of development from my present adult point of view, with a sense of nostalgia and longing for the past. I think this strange convergence of different temporal perspectives brings an emotional complexity to the pictures.

There does appear to be a certain emphasis on the quite formative teenage years, that sort of in-between state where a lot of things are in flux, and it can be hard to resolve certain feelings about that stage in life. Was this project a way of doing that?

Absolutely. Although I didn’t intend this beforehand, the project turned out to be strangely therapeutic. This convergence of temporal perspectives forced me to mediate between different parts of myself, as I saw them coming to life in the people I photographed. I’ve always been fascinated by the turbulent time of adolescence, when the self is in flux, and it’s all about trying on different identities. Sometimes I think I never grew out of that phase, and that’s probably true of most artists! To make good art, I think you need to keep questioning; you need to preserve a healthy amount of doubt. And in a sense that’s what art does: it returns us to a state of wondrous uncertainty, where anything is possible. It makes us like children again.

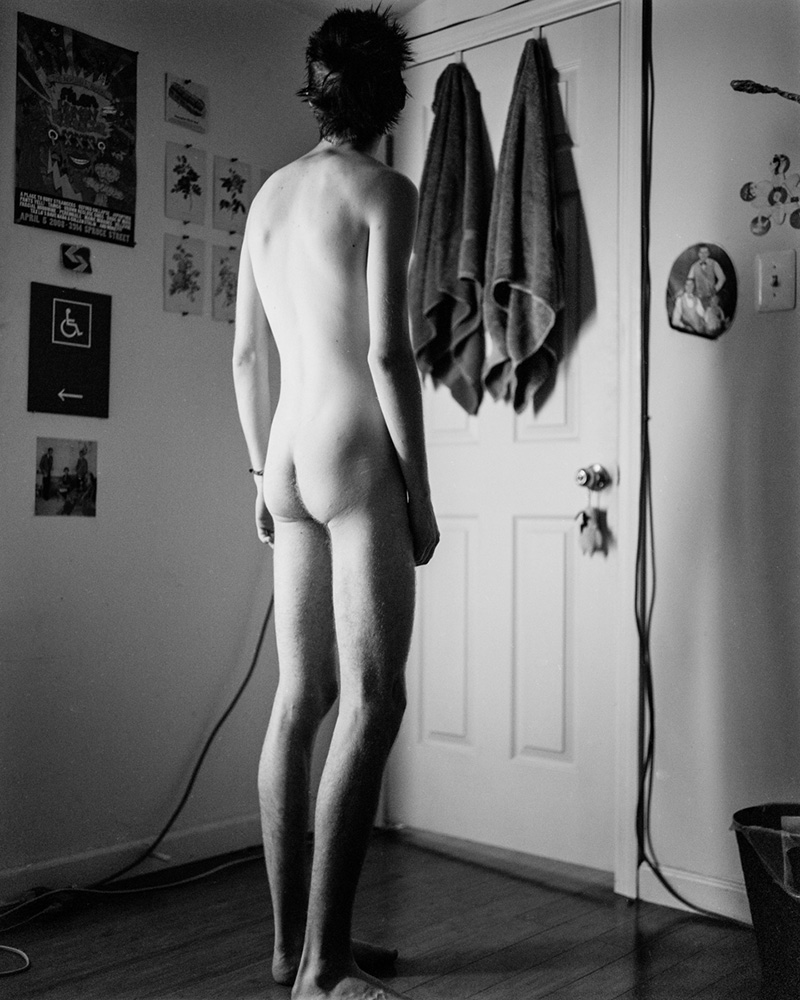

The photographs of people around the town feel very intimate. Were these people you knew prior to you taking their picture?

SC: A few of them I’ve known my whole life, but many were strangers, or recent acquaintances. That’s one of the things I love about portraiture: the intimacy of a portrait is independent from the intimacy of an ongoing relationship. Thanks to the magic of photography (paired with skill and good luck) you can create a very intimate moment with someone you barely know. Conversely, it can be very hard to make a good portrait of someone you know well. In the end, my personal history with the sitter doesn’t matter. I’m just creating a screen for viewers to project their own fantasies and associations — enabling them to create their own narratives.

The notion of loneliness, or perhaps better ‘separation’, is something that seems to be projected by all of the people that you have photographed. Even the couple, embraced in each other’s arms—they seem shut off from the rest of the world. Was this sense of isolation something that you felt growing up?

Definitely. I was a very lonely child, and connection to community remains a complicated subject for me. In my photography, I am most often drawn to the solitary figure. Thus the decision to include only one image of a couple was very considered. Perhaps the (imagined) intimacy these two share is what the rest of those lonely boys are craving?

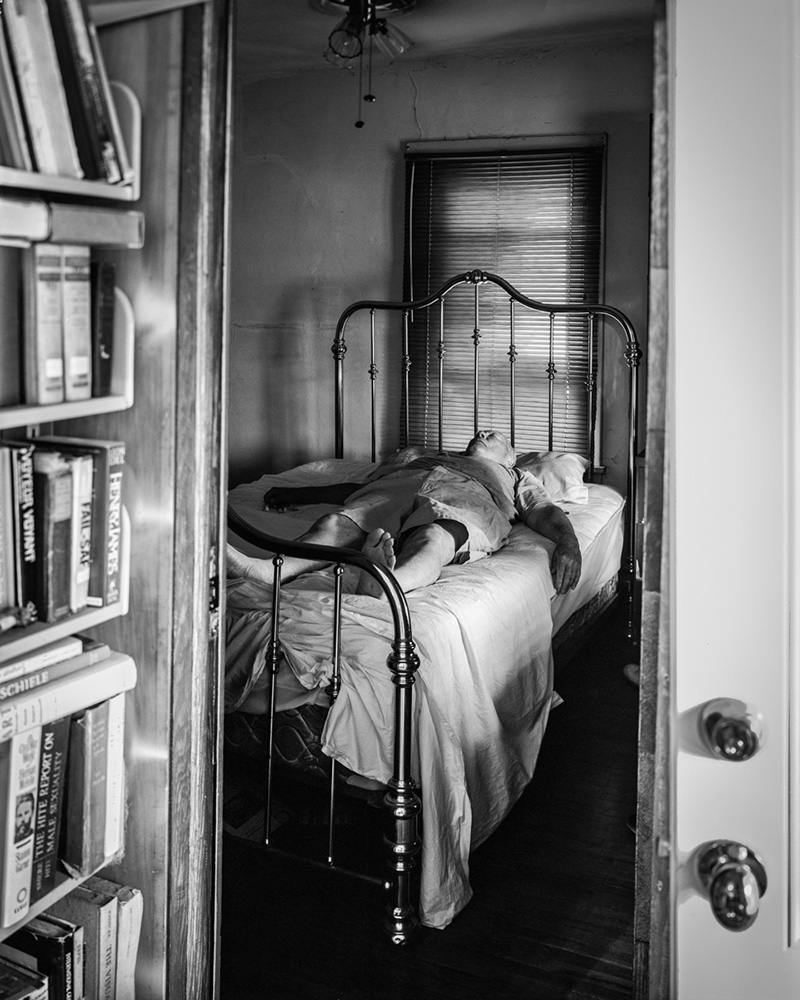

When I began looking at your photographs, I was drawn to the idea of loneliness as the most prominent thread running through the lives of these individuals . The more I think about it though, and the more I come back to look at the images, the aura of loneliness and isolation seems to dissipate. I doubt many of the people you chose to photograph have met each other, but they have met you. With you as the significant link between all of these people, their situations and imagined lives suddenly feel so much fuller and with more promise. In this microcosmic story that you have put together, they have each other, and in that they are most definitely not alone. I would be very interested to hear what you think with regards to that.

Well, I think that’s a lovely – and quite flattering – interpretation. That said, I’m sure many of them are not lonely people at all. If they seem lonely, it’s because I photographed them in a way that reflects my own loneliness. I certainly don’t presume to represent who they are as individuals. But you’re right; within the fictional world I’ve created, they are connected to each other, and to me. Like characters in a novel, they have been given another life; a parallel existence that might in some small way outlive their present-day reality. I won’t go so far as to say I’ve immortalised them, but I do hope I’ve portrayed them in a way that will continue to resonate with viewers into the future.

I think you’re right, their presence does resonate onwards and will continue to do so. I’m not sure how other people have commented on the work, but I think a viewer will project themselves or others they know into the place of the individual photographed. Perhaps that’s quite shallow in a way, but I find with images such as yours, that hold enough mystique to allow it, it becomes an inevitability that people will impress their own memories and relations onto them. Does that bother you, or is it something that you appreciate?

I think that’s inevitable with portraiture, and I embrace it and work with it.

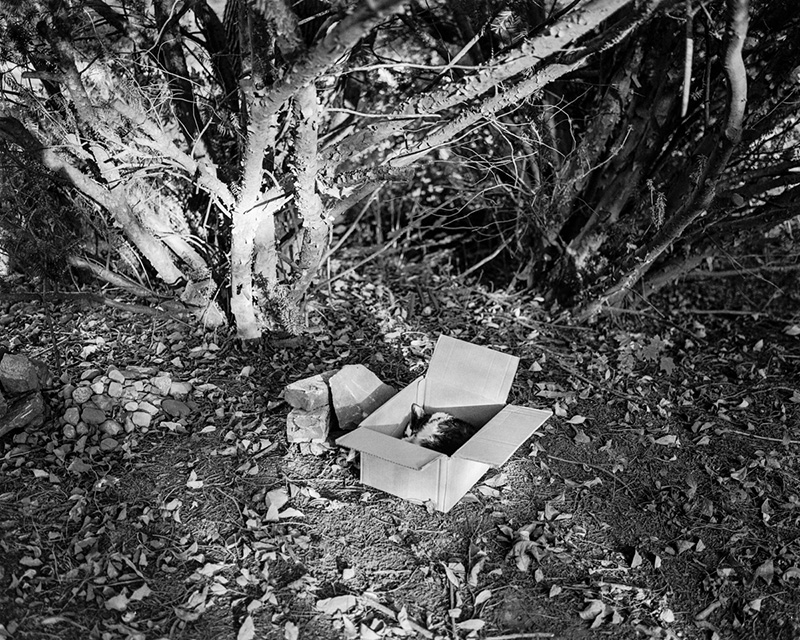

As beautiful as the portraits are, and certainly alluring from the perspective of the viewer in terms of seeking to extrapolate some sense of identity from the subject, I’m perhaps more intrigued by the non-portrait photographs that you took. They seem to present a quite recognizable idea of adolescence in American Suburbia. Can you talk a little more about why you chose to include them in the series?

Well, first I would be careful about the term “American Suburbia”. I grew up in a small town, where there is an intimacy that is quite different from the stereotypical suburban alienation. It’s a town where people know and trust each other, where doors are left unlocked, and where from a very young age, I could walk or bike just about anywhere. My childhood may have been lonely, but I always felt safe and free to explore… which is very important. As a town with a long progressive history (the college there was the first to admit women and blacks) there is also a strong utopian aura to the place. I’m not saying it was paradise; like any town it is full of shadows and secrets, but it’s far from a bland suburbia. As least for me, it was a place of magic and wonder, and that’s one of the things that drew me back.

Still, I’m glad you asked the question! Most people just focus on the portraits. I included the other images to provide some context, and to give a sense of rhythm to the series, and also to offer the viewer some respite from the intensity of each encounter with a person. But of course they are not random, and each was chosen and placed in the sequence for a reason. Can you tell me which ones in particular evoke the experience of adolescence?

The most obvious one that comes to mind is the image of the school corridor, lined with lockers and daylight flowing through the doorway in front. At first it evokes the desire to ditch class and go see your friends, yet when framed within the context of these portraits, it presents itself as much more giving to the narrative that you are telling. Our view is lined with these compartments, each containing hidden gems and stories—evoking ‘magic and wonder’ like you said—and at the end everything crystallizes and becomes much clearer. There’s a similar sentiment with the photograph you took of the tree-lined street, with the sun breaking through the leaves. The instances in which these two are taken seems very short lived—they appear as if they were taken quickly, in motion. Yet the impression of them—that feeling of magic and wonder, as you say—carries on throughout the series. Why did you include those two in particular?

Well, they weren’t taken any more quickly than others in the series, but I’m glad to hear that the feeling carries through. They were both made in places that are heavily charged with memories, and feelings I had growing up in that town. On the left in the hallway is the locker I went to every day in high school, and for me that picture evokes a sense of suffocation, but also the feeling of relief when school empties out at the end of the day. It was actually taken during the summer when the building was empty, and standing in that silent hallway filled me with emotion. Twenty years later, I could still hear the teenage chaos, the laughing and bullying voices I’d endured so long ago. I’ve always loved revisiting sites of intense experience, once they are emptied of humans. As a teen I used to walk the town at night, returning to locations of daytime dramas. As early as age seven, I remember peering into my empty classroom during the summer, filled with nostalgia for what I’d experienced at age six, as though it were lifetimes ago.

How long did it take you to finish the project? You spoke about going home for a high school reunion, was it completed during this time, or was that when the desire to make the work started?

The project as you’ve seen it was shot mostly over the course of two years. I made several trips to Ohio, staying anywhere from a week to two months. In the end I decided to include a few images made elsewhere or earlier, so long as they had the same tenor, or seemed to belong in the same fictional world.

So some of the images were not made in your hometown, is that right? That’s interesting then that you chose to include those, as I was under the impression these were all in the same place. Did the initial trip back spark something in you to continue this onwards wherever you were?

Yes, a few of them are from other places. I feel hesitant to disclose this, as though I could be judged for violating some photojournalistic code of ethics! But clearly this is no reportage – rather, I’m creating a fictional world, so any photo that adds to that world should become part of it. I’m glad you had the impression they are all from the same place, because they are! But it’s a psychological place –– the geography is secondary.

The series seems quite tight and concise in a way. Do you have plans to expand on it, or is the project over for you now?

I think this is the kind of project that’s never really over. There are so many more images I could have included, and I make somewhat different edits of the material according to where I’m showing it. Because there are several themes running through the work, it can be taken in different directions. For example, I was invited to be in a group show on the theme of belonging, so I worked with the curator on a selection that speaks to the experience of belonging (or not) in the place where you grew up.

I can imagine chronicling my hometown for the rest of my life. Maybe I’ll publish an epic version when I’m 80, but for now I wanted to present a concise edit that would leave the viewer wanting more, rather than overwhelmed. I’m no longer specifically focussed on photographing in my hometown, but I continue to visit, and every so often I make a picture that could fit in the series. I’ve also been invited to develop and expand the work this summer, during residencies in France and Austria.

Will those be the same or different projects? I don’t really think in terms of isolated projects – all my work is interconnected. My practice is more rhizomatic, with lines of investigation that diverge and then loop back upon themselves. I resist the convention of the separate “series”, even though I made one in order to share this work in a concise way. I think photographs can function in more than one context. In my current work I’ve been mixing some older, forgotten images with brand new material.

I like the idea of documenting something like this through your entire life. It’s suddenly reminiscent of Linklater’s Boyhood. Do your impressions change when you go back to photograph, or are your current feelings just more entrenched?

Well, memory is a strange thing. Each time I go back I remember different layers – different points in time emerge more strongly. Our brains build memories over time, and some get amplified, while others are “forgotten” to make room for newer, or more relevant memories. So now, when I return, I not only remember my original “boyhood” (is there an original?) but the memories of making this project are superimposed as well. So everything ends up in the mix, and informs everything else. I will say that when I started the project, I was inspired by my memory of taking pictures in high school, before I began to study photography. I had an “innocent”, “naive” approach – at least that’s how I remember it! This was also part of what led me to return to black and white.

It’s funny that you mention Boyhood… I really wanted to like that movie. But I’m thinking more along the lines of Paterson, William Carlos William’s epic poem about the town in New Jersey. But of course that would become a much larger project –– and one I have the rest of my life to complete.