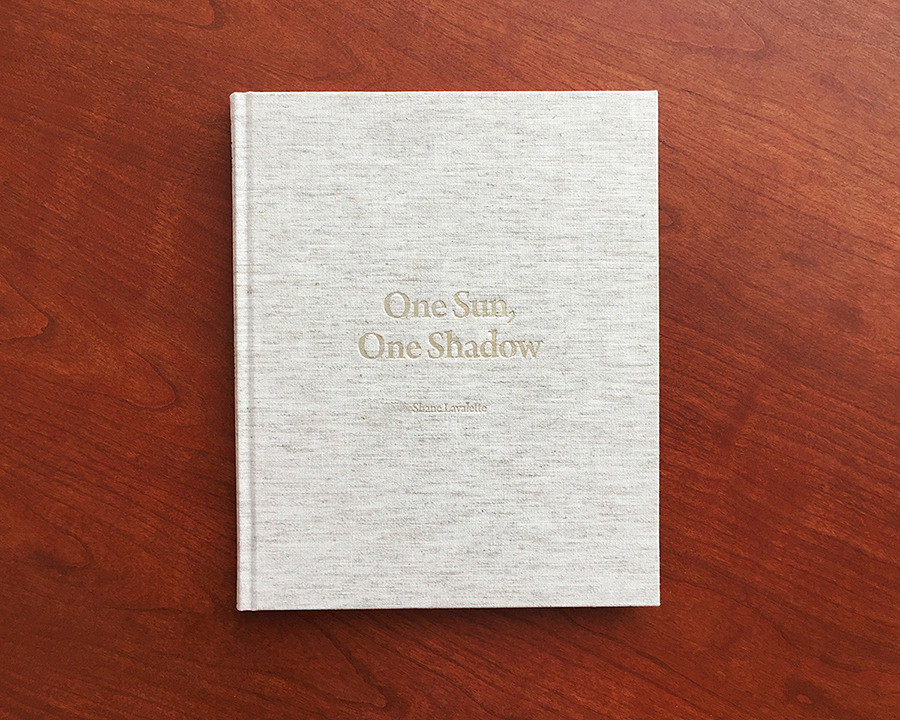

Interview – Shane Lavalette: One Sun, One Shadow

Since 1996, the High Museum in Atlanta has been commissioning established and emerging photographers to produce work inspired by the American South. The title of the project is “Picturing the South” and in 2011 Shane Lavalette, together with Martin Parr and Kael Alford, were given the challenging task. Challenging not only because of the broadness of the assignment, but also because when dealing with photographic commissions it’s very hard not to look back to the great names of photo history and become quite nervous under the pressure of comparison. Shane decided to approach the region by thinking about its music history and how much music defines the landscape around us and our own experiences of them.

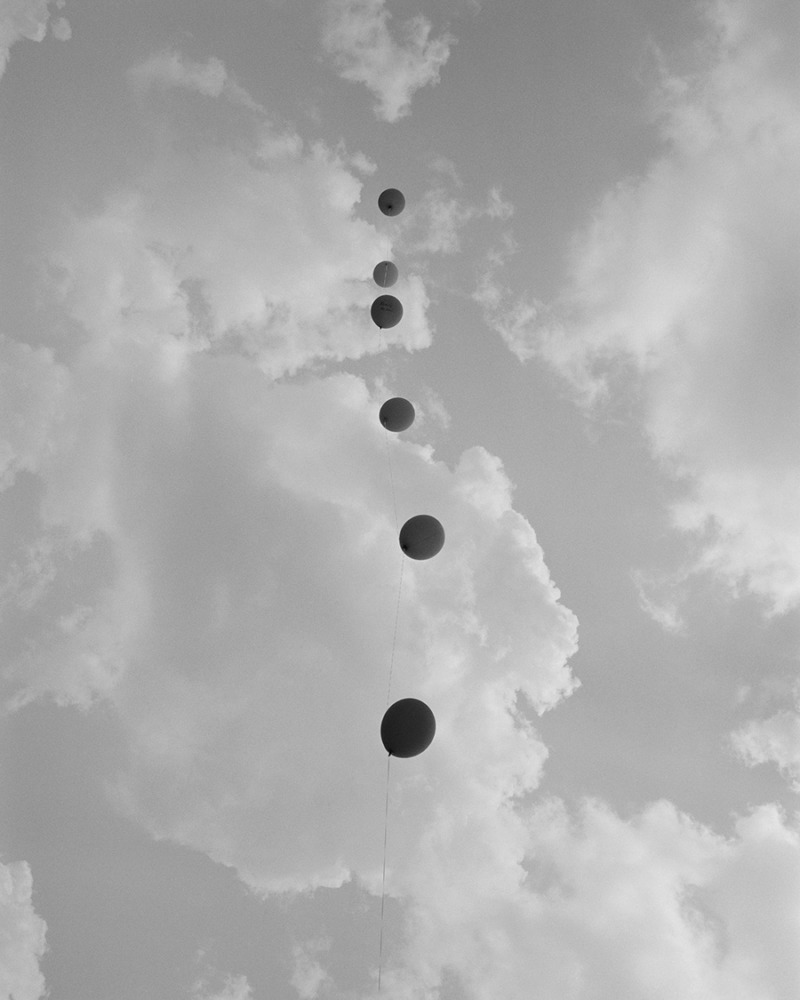

A path that could have easily brought him to talk about the dangerous clichés of the binomial ‘Music/South’ in a foregone manner, but that in fact was very nicely balanced and culminated in his book titled One Sun, One Shadow, a thoughtful publication that has nothing to envy of its past precursors. Flipping through these pages, we are never overwhelmed by the loudness of these places. The soundtrack of this work is made by the sounds of the nature and the voices of the people Shane met during his journey. But these sounds are never in our faces; on the contrary they are always mediated by the beautiful photographs. Music also comes to mind when we analyse the structure of the book. The impeccable editing allows each image to speak with its own voice, contributing to the overall narration. As in a Greek chorus, every single page contributes to, or establishes a relationship with other parts of the book. And through a careful rhythm made of repetitions and echoes, we are brought into Shane’s poetic journey into the deep American South.

I think the nature of the South reflects both a deep beauty and a lingering darkness

Before we talk more specifically about the book, I am curious to know a little more about the genesis of the work included in One Sun, One Shadow. In fact, you have taken many of the photographs as part of the project “Picturing the South” that was a commissioned by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in 2010, and exhibited there alongside Martin Parr and Kael Alford in 2012. How and where do you start when you have a commission that sounds as broad and important as picturing a geographical region? I’d like to know about this experience, and also understand what your inspiration was when you started the commission.

When the High Museum said they would like to commission me to make a new body of work, it was both exciting and a bit overwhelming. Of course I was thrilled, but there was a serious feeling of unworthiness that I had to wrestle with before I could really start thinking about what to do. I was aware that they had worked with Sally Mann, Emmet Gowin, Richard Misrach, Alec Soth, among others—a list of artists that I admired greatly. It turned out that they were keen to work with a mix of new artists who have varying relationships to the region, and they were seemingly interested in me as a young image-maker (I was twenty-three at the time) with an outside perspective on the South. I felt extremely grateful for the opportunity, and without their support I simply could not have undertaken the project in the same way.

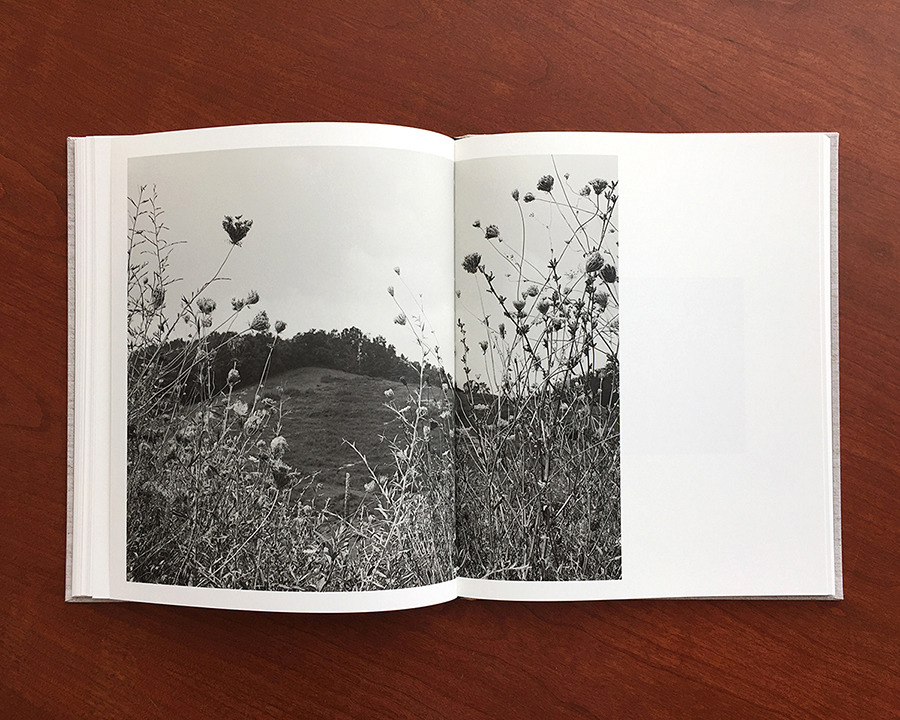

I thought long and hard about the ways I could approach photographing. I hadn’t previously traveled through the Southern states, so my idea of what the South was like was generally informed by films I had seen, the history of photography, and music. I quickly realized that I would have to find an entry point, and music felt like the most interesting and open-ended, in terms of its relationship with the static image. At the time I was getting really into in old time, blues, and gospel music and was engrossed in the subjects of the songs—often stories about love, labor, religion, or subjects like nature, struggle, and loss. I was also intrigued by music’s role as a form of oral history, and the idea that music is very much informed by the place where it is made (and vice-versa, that our understanding of a place can be informed by music). I wanted to explore this idea through images, in a more abstract sense.

I’m wondering if you decided your itinerary based on the places that have most directly shaped the history of southern music. I’m thinking about Memphis, for example.

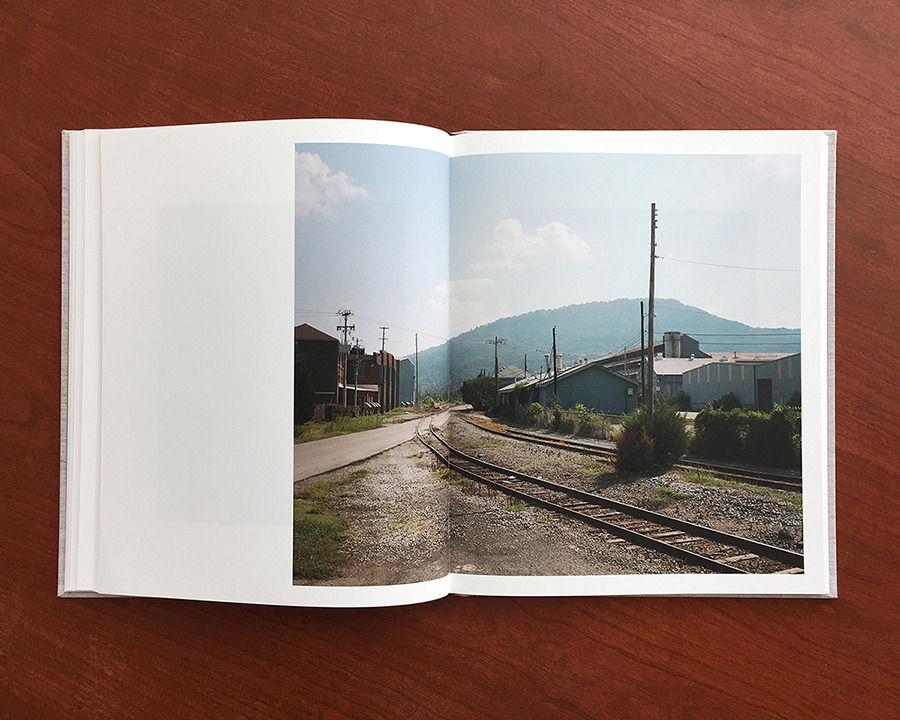

The musical history of the South is extremely rich. I set out with a map that incorporated a few people and locations that I thought could be significant to the work (places like Clarksdale, MS and Memphis, TN), but decisively wanted to remain open to explore things off of the beaten path. I’ve talked about the importance of “yes” in some other conversations about my process of working. When I set out to make images, one thing leads to the next. If someone suggests that I visit a place or meet someone, I always follow that.

I had a general route outlined before I began travelling, down through the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, etc. I spent the first summer living out of my car, working on the project for almost three months straight. The project was shot on film and I didn’t see any of those photographs until I was back home scanning sometime in the fall. I travelled again the following summer, and made a few other specific trips that weren’t as long. Because I photographed primarily in the summer, the heat of the South became an underlying subject of the work.

I think it’s a courageous decision to explore the landscapes of the South through the subject of music. I say courageous because the connection of music might sound cliché when we talk about the American South, but you approach it with such a delicate touch that it becomes mediated, and not overstated.

I appreciate that. I knew I was diving into something much bigger than me to attempt a project that explores the subject of music and its relationship to the American South. In a sense, the themes within traditional songs are now clichés of the region, but at the same time a real part of the Southern identity. I also knew that I was walking in the footsteps of so many great photographers that had come before me, and that I would have to be aware of that history as I was working. Others have said that I make “quiet” photographs, which is interesting considering my exploration of sound with this project. I am really fascinated by the power of looking, and have experienced the ways in which a carefully seen image of a seemingly simple subject can stir deep and complex feelings, especially when placed in proximity to other images that inform it. I certainly explore this with my own work, by taking a lot of care in how the images come together.

Tim Davis, who describes your work in the book’s essay, writes: “They are quiet pictures that build to a boisterous whole.” Your book is chorale in the sense that each image speaks its own voice but really resonates with others, but also because you educate us through your deep exploration of subjects and the layers to discover within the work. What do you hope for viewers to see in your pictures?

My process of photographing involved a lot of walking. Exploring by foot is important to the work because I wanted to find myself in places that people might just pass by if they weren’t from that area. In editing the book, I thought about the feeling of looking at things while going for a walk. I want a viewer to feel like they can easily step into the photographs in that way. Some of the connections between images are more obvious and others may take a multiple readings to see, or may never be seen. I imagine that different viewers may have rather different readings of the book, and I welcome that.

When did you start thinking about publishing One Sun, One Shadow, and why did you see the project as a book?

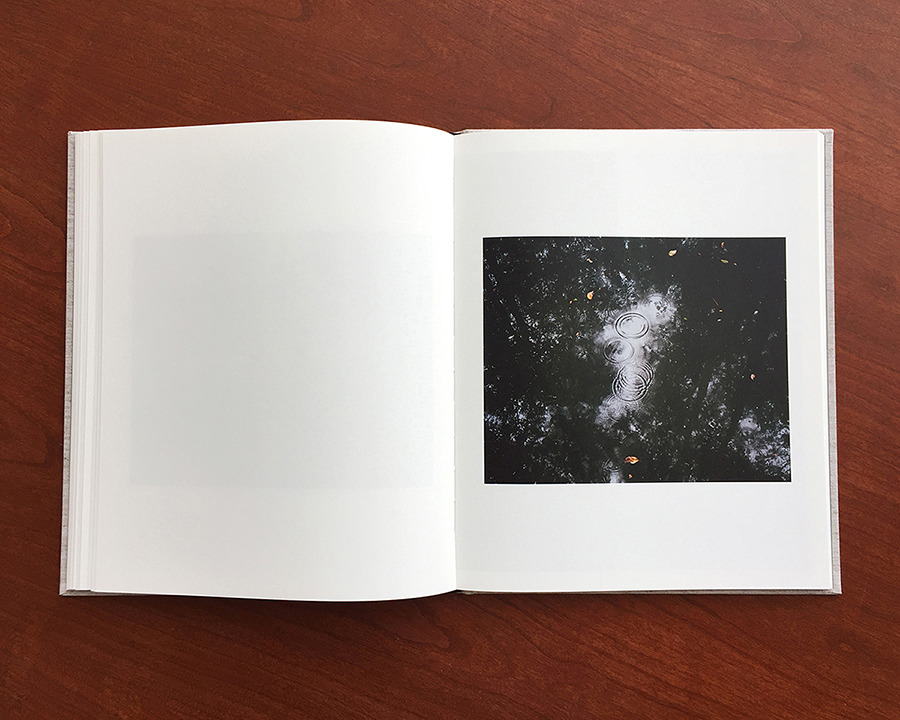

For a few years before I began this project, I had been working with other artists to edit and publish books of their work. I don’t believe that a book should be published just for the sake of making it, but I’m very much invested in the idea of the “intentional” artist’s book, where the format of the book reflects the work in some way. Though I knew I wanted to make a rather traditional monograph upon first glance, I felt the subject of music was particularly suited to the book form and really wanted to play with that as a way to push the form. Within the pages of a book, you can develop a tempo, a melody, or embrace musical elements like harmony and repetition. I really wanted to explore these possibilities, through the edit and sequence of images, as well as how the resonance of a photograph can change through its placement with another, as with music notes. It’s a basic idea, but thinking through the photographs in this sense presented a new way to view the images.

Repetition is an interesting element in the work. I noticed, for example, that you have included an image of a burning forest in three different parts of the book. It’s almost like a musical refrain. Can you tell us about that image?

There are a number of things that repeat in the book, either in the same form, back to back, or in more obscure ways. The burning forest was a memorable photographic experience. I spotted the natural burn from a few miles away while driving and immediately hopped off the highway, and meandered through back roads to find my way to it. I recall shooting a few rolls of film of the fire, and at one point found myself walking through the blazing woods, over crackling glowing pine needles, almost entirely surrounded by it. At one point, the smoke was so thick that it engulfed me, and my eyes began watering uncontrollably. Looking through tears, I made as many pictures as I could before retreating. It was a visceral experience. The fire can be read in various ways within the work, and segments the book almost like chapters. Fire brings destruction, but also regrowth.

I also knew that I was walking in the footsteps of so many great photographers that had come before me, and that I would have to be aware of that history as I was working.

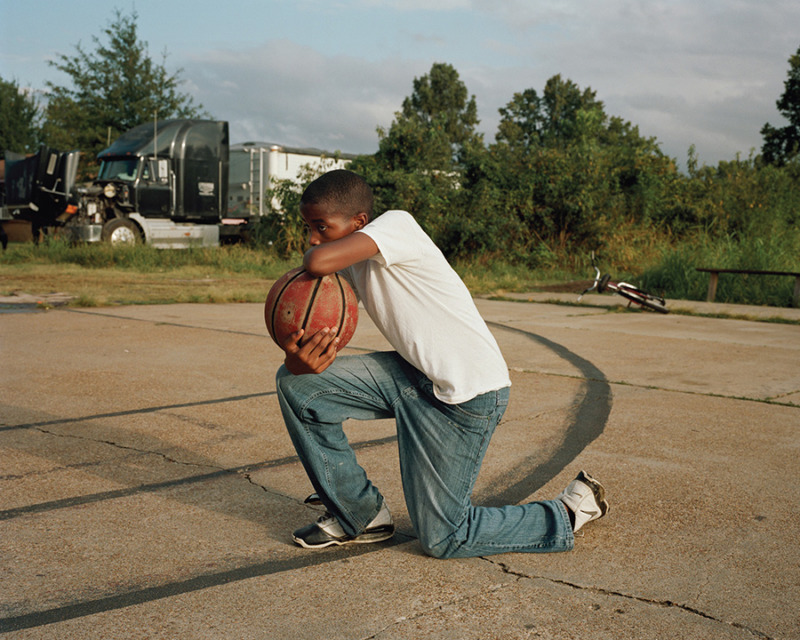

When I look at this work, I have the feeling that you have spent a lot of time alone during your journeys. In your landscapes there is a sense of loneliness that it’s both calming and maybe a bit frightening. The portraits somehow give me this sense of solitude as well. The people in your images feel archetypical, like symbols within a story. Who are they and why did you decide to include them?

I traveled with others while working on the project, and stayed with folks who were kind enough to offer a room or their couch. I do think I tend to recede into my own head while making work, though. This is something that probably comes through most directly in the landscapes, because the portraits involve some kind of human exchange. In terms of the people, some are of musicians or connected to music in some way, but many are actually complete strangers that I met in passing and was drawn to. I think a good portrait is always interesting because it tells a story. It inherently says something about who the person is, but it also only says so much—it invites the viewer to see something in the person which may or may not be true.

I’m glad that you get a sense of something lurking in the landscapes. I think the nature of the South reflects both a deep beauty and a lingering darkness. The title of the project itself, One Sun, One Shadow, alludes to this idea.

What kind of music was particularly inspiring, or what were you listening to while traveling?

I made myself a mix of songs that were by both earlier and more recent musicians, many of which were directly rooted in the South as well as songs that take inspiration from that lineage. It included the likes of Blind Willie Johnson, Clarence Ashley, Elizabeth Cotten, Doc Watson, The Fairfield Four, Kokomo Arnold, Dock Boggs, Snuffy Jenkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jack Rose, Sam Amidon, and Nina Simone, among others.

You recently had the first solo exhibition of One Sun, One Shadow at Robert Morat Galerie in Germany. How do you approach exhibiting this work, when it seems like you’ve focused on the book as the ideal form for the project?

When I exhibited this work in its early stages as part of the High Museum’s “Picturing the South” exhibition, I was really happy with the display, but thought a lot about how the physical space could have been more activated through the musicality of installation itself. With the opportunity to produce a solo show, I knew I wanted to be a bit more playful with how the images were installed in the gallery, so in addition to varying scale of photographs we showed some images up higher on the wall, some lower, nudged together, further apart, etc. I think this approach underscored the musical quality of the work, without being heavy handed, and gave emphasis to some of relationships between images that are explored in the book. In the new year, I will have a few other shows of this work and I hope to continue to push this idea and find new connections.

For the past five years you have also been working as the director at Light Work, where you produce exhibitions and publications by other artists and oversee the artist-in-residence program, among other things. How is that going? You must be in contact with many photographers and have an interesting viewpoint on the state of photography today…

I ended up working with Light Work after doing a residency in Syracuse in 2011. I had a really profound experience and was interested in supporting other artists in that way, through a non-profit. The residency program is just one of Light Work’s programs but it’s certainly one of the more well-known and meaningful. It invites twelve artists per year to come to Syracuse to devote one month to the development of their work. Each artist receives a $5,000 stipend, an apartment to stay in, and generous staff support. Artists come to do everything from making new photographs, scanning, printing, editing, and prepress work for photobooks. This past year we received nearly 1,000 application for the residency program, and are seeing an exponential increase in the international applications that are coming our way. It’s a daunting task to review all of the applications, but it’s something I’m really grateful to be able to be a part of. As you said, it does give some sense of the state of photography, the concerns and conversations that artists are having right now.

You regularly shoot editorial work as well, having photographed for publications like The New Yorker, Bloomberg Businessweek, The Wire, Wallpaper, Monocle, and The Guardian, among others. Do these assignments feed into your personal projects or are they something else entirely?

Though I’m focused on my own practice I do enjoy the challenges of editorial assignments and have been lucky to shoot some truly interesting and inspiring stories. Though it’s not likely to be directly connected to my personal work, it does force me into unexpected situations and is always a learning experience. I don’t believe that great work is made when you’re very comfortable, so I always try to keep that in mind and stay open to trying things I might not imagine myself doing.

Do you have any new projects coming up?

I’m working on a few new projects right now, which I’m really excited about. My primary focus has been on another large photographic commission that I shot in Switzerland this year. The project ventures into new territory for me, yet is an extension of my interest in place, history, and time. An exhibition of this work will open in 2017 at Fotostiftung Schweiz in Winterthur, and then travel to Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne. I’m exploring ideas for another book down the road.

One Sun, One Shadow is available online on Lavalette’s website

Lavalette will also be signing copies of One Sun, One Shadow at Printed Matter, 4 November at 6PM.