Other Histories: An Interview with Kameelah Janan Rasheed

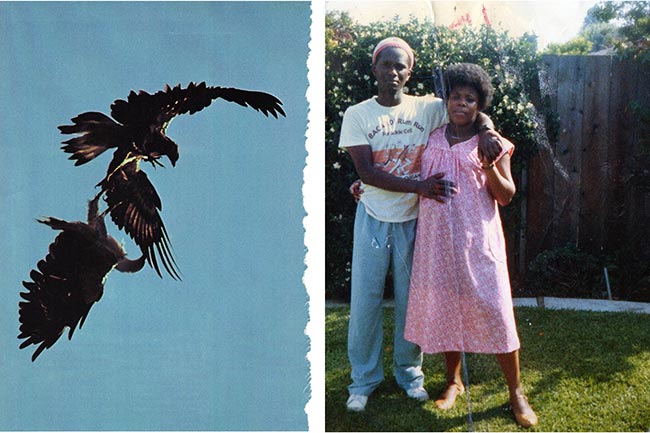

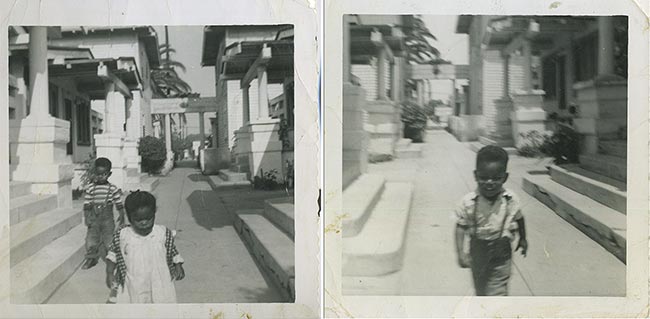

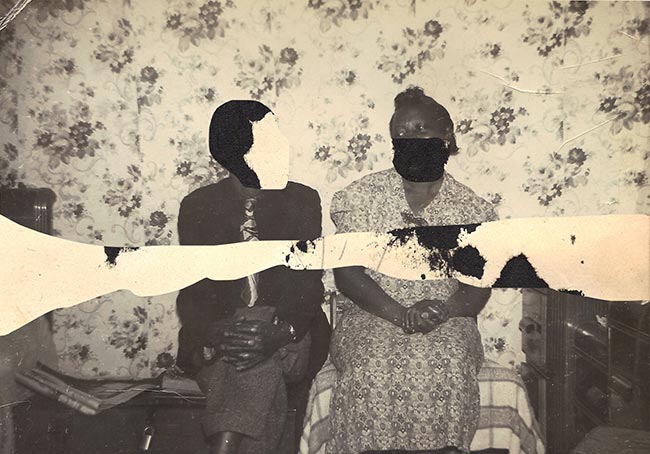

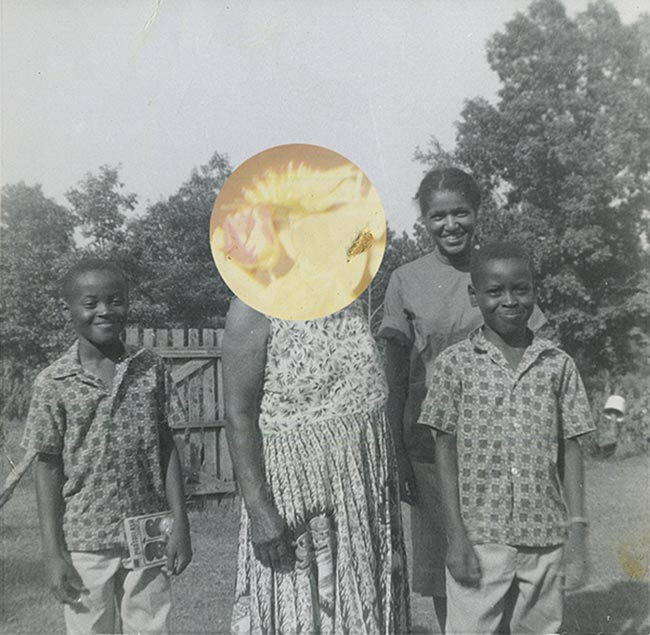

Photography can encompass a unique and diverse range of social roles: it is how we are seen and, in turn, how we have come to see ourselves. The sum of this material, both public and private, makes for a composite social image. Confronting the nature of that visibility – and its manifold contradictions – must be thought of as key to the work of Kameelah Janan Rasheed. What she reveals is the conflicted interior of our cultural narratives, as in her multi-part collage series No Instructions for Assembly. Cutting across (though more often tearing or breaking through) the image is a sort of visual excavation, to emphasise the logic of those absences that mark not only a particular photograph, but also of the institutional rhetoric that has shaped it – representation is never impartial, rather it must also be understood as a way to assert control, marking the advance of a convoluted historical agenda.

The archive is a site where specific discourses of power can manifest themselves – indeed, it can also be thought of as an instrument of that power. So to consider the archival as a critical subject is to address those discursive structures that produce meaning within its confines, not only on their own terms, but also because of the larger narratives that anchor them; interfering with the ‘machinery’ of the archive, as Janan Rasheed does, is to disturb the nominal certainty of those discourses that otherwise resist contradiction. It is also to discover a sort of poetic dissonance that can just as easily be understood as a mode of critique. Although the imagery in her work is clearly derived from a range of contexts – some of which might not be thought of as being ‘archival’ in the conventional sense – the logic that sustains all these varied uses of photography is still moved by the same impulse to present a specific ‘view’ of the world; collage is a means of turning such methods against their more didactic uses by taking control of those narrative resources in order to reveal the ways in which they are constructed.

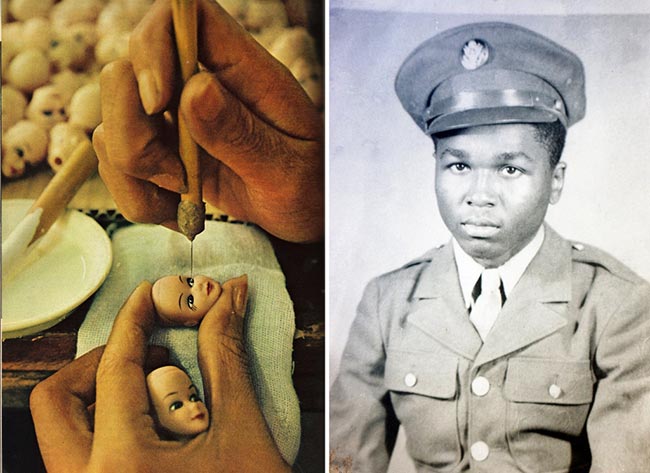

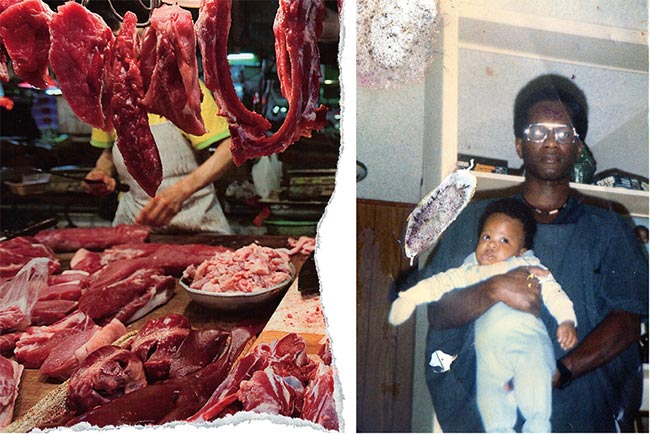

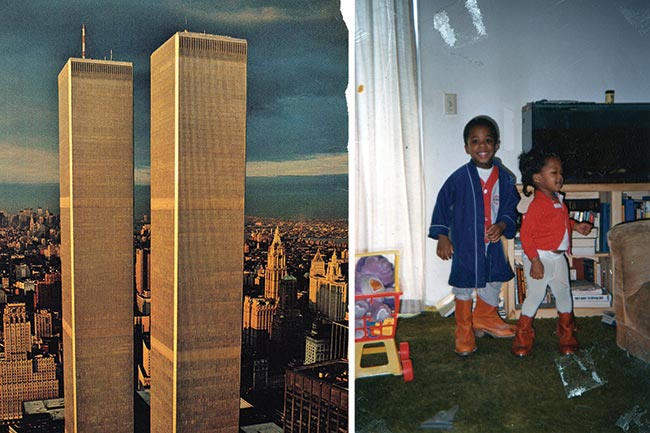

Here it is embodied by the (visual and conceptual) tension that Janan Rasheed orchestrates between two or more different images – this archival enterprise is intended to locate an implicitly personal dimension within the categorical order of (cultural) narratives, forcing deeper, more elusive connections out into the open, while also coming to terms with the complex material presence of photographic images, their status as objects imbued with meaning. In the statement that accompanies the work she describes it as an attempt to ‘re-imagine a history’ for herself and there is indeed the sense that it can fulfill this role, at least in part. But this is also a history that addresses its own necessary degree of incompleteness, where stories have gone untold because the means to tell them was out of reach. Janan Rasheed, then, is charting a territory shaped by histories that are at once personal and cultural, in order to establish the often fraught points at which they intersect.

What first brought you to photography – and, I suppose, to collage in particular?

My parents did not let us watch much television or listen to the radio much as children. We had a couple of records – Gil Scott-Heron, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson and a Babyface cassette tape. We had a lot of books. My dad might rent some vetted movies from Blockbuster. I spent much of my time either reading, doing experiments with my Biology teacher in his lab, collecting creek water samples, running around with my four brothers or making art. I sketched a lot – trees, faces, and imaginary magical beings. Specifically, I came to photography when living in Cape Town, South Africa as an exchange student, and again in Johannesburg, South Africa as a Fulbright Scholar. I was photographing protests and community events. I loved the process of documentation and interviewing. Collage helped me deal with things that were happening in my life – homelessness, cancer, etc. Collage helps me negotiate how to create narratives from material as well as psychological fragments.

I embrace the fluidity of my artistic practice – I don’t quite identify as photographer or a collage artist. I also make small hand-sewn books and objects, draw textile designs, interview other artists, and write fiction (albeit secretly). In 2014, I am curating a trans-Atlantic show around gender presentation and queerness, am wrapping up the curating of an experimental show at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and facilitate art-making workshops with youth in traditional spaces like the Brooklyn Museum as well as at community centres. Most people would not know that because part of what I formally embraced as being ‘what professional artists do’ meant limiting the presentation of my self-presentation to one plane of existence so that an audience can ‘read’ my body of work. In the closing line of poet Harryette Mullen’s ‘S*PeRM**K*T’ she writes, ‘speed / readers skim the white space of this galaxy’, which I have always interpreted as an observation of the manner in which the reading and viewing of certain ‘texts’ – visual texts included – has become a hasty affair; one in which the audience quickly refers to formulas and expectations, rather than approach works newly and patiently to extract the nuances. This is the danger of self-replicating tropes and performances of identity on one plane: there is a predictability which gives others a license to skim-read your existence.

My practice is liminal and boundless in that I’d prefer not to be categorised with ease because when my curiosity carries me elsewhere, I am not interested explaining the logic behind what seems like a ‘transition’. I am not transitioning – I was never stationary. My artistic practice is nomadic insofar as I am wedded to certain rituals and time investments, but when and where I perform them is not dependent on a medium. I don’t want what I do to be exhaustible. Once, I have ‘arrived’ at photography, then what? In an interview with BOMB magazine, Lorna Simpson said, ‘People believe that you should have a particular signature for the rest of your life. I can’t even begin to imagine what kind of life that would be.’ And I agree. While my bios try to give an exhaustive list of titles, it creates a sense of arrival, rather than journey. And putting up a banner of artistic arrival feels like artistic suicide. When black opera singer Jessye Norman was asked why she chose opera, she responded, ‘Pigeonholes are only comfortable for pigeons.’ Since I am not a pigeon or part of any Columbidae bird clade, I try to wiggle out.

It’s clear that your practice is, for want of a more elegant term, quite socially engaged. What do you think the place of activism in art is?

I am hesitant to call my work ‘socially engaged’ not because I do not believe my work lives in the canon of what is seen as socially engaged art, but because it implies that other works and other artists live in a vacuum where they do not engage with the world. Traditionally, what has been segregated into the ‘socially engaged’ art neighborhood is work whose aesthetic value is eclipsed by the real or perceived political message or utilitarian purpose. This is unfortunate. It is unfortunate because it is seen in this simplistic dichotomy of art or activism as if the marriage of both is some unwelcome 1940s miscegenation tale. It is unfortunate because it pushes people away from this kind of work for fear that they will not be taken seriously by the commercial art world. It is unfortunate because we lose the deepness of work by pinning it between two imaginary polar opposites and asking it to dance between and on the poles. It is unfortunate because all art is political, whether the artists want to acknowledge it or not. Art is narrative in its nature and each piece of art we create is an active choice to prioritise one narrative over others. This is political. What is political is the choice to be explicit about this narrative direction.

The notion of art as activism is tricky only because we chose to make a mess of it. The work of Zanele Muholi, a South African artist, is striking. In her own words, she has dedicated herself to ‘mapping and archiving a visual history of black lesbians’. She lives in the grey zone between artist and activist. Sometimes, people will forget that even while she is doing the work of activating buried narratives, there is an aesthetic quality of her work that also needs to be acknowledged. She crafts portraits and intimate candid photographs in a way that is not simply utilitarian. Her work is beautiful and explicitly political which I think is a privileged balance. As for my work, I am working toward that privileged balance.

The notion of the archive seems to play a key role in this work, both as the site of specific historical narratives and as a territory that can be reclaimed if necessary. What does the ‘archival’ mean to you?

The archive and what is considered as archivable is a privileged space. Some people and narratives live (or are forced to live) outside the collection scope and policies of libraries and other institutions. This results in a narrative imbalance where there are institutionalised traces of existence for some communities, while others disappear, get buried in the margins, or collapsed into footnotes. It is the margins and footnotes where my work begins and to where it returns. My work seeks to create an archive from historical footnotes and marginal images, objects, and texts I have collected from a variety of sites. Combining material culture and found images, I am curious about how the archive can be reborn in non-traditional and more democratic sites that take into consideration both access and intent. Finally, I am concerned with how art can be archival and how the archive itself in its physical organization and spatial location is rooted in a particular taxonomical aesthetic.

Looking at No Instructions for Assembly it seems to me that you’re more interested in exploring the tension between the narratives suggested by particular images than you are in using collage as a way to actually ‘create’ an image. Do you think that’s the case?

The tension and conversation between the images is quite important, but I also love the methodology behind collage – suturing, ripping, slicing, and being the Frankenstein of (re)memory or playing an insular version of exquisite corpse. Building on this Frankenstein-esqe mode of working, in the introduction of Recyclopedia: Trimmings, S*PeRM**K*T, and Muse & Drudge (2006), Harryette Mullen writes that ‘[i]f the encyclopedia collects general knowledge, the recyclopedia salvages and finds imaginative uses for knowledge. That’s what poetry does when it remakes and renews words, images, and ideas, transforming surplus cultural information into something unexpected.’ Likewise, my work seeks to make use of surplus cultural information to conjure up new narrative possibilities and to craft unexpected relationships between textual and visual data. Central to my artistic practice is the nearly compulsive accumulation of disparate visual and textual data from estate sales, digitized portals, eBay, public libraries, and family collections. I try to create simple images through textual and visual operations that articulate varied permutations and possibilities to explore both the hermetic private histories as well as larger public histories. These disparate images and text create their own logic and grammar – an internal language that I hope invites the audience into an intimate space where they can engage in mental play with the work. Tension is a part of this language. The collage process is less about layering images and more about asking disparate images and text to ‘speak’ to one another.

Throughout it all, collage becomes intriguing as a form of artistic reparations – getting back what was lost through suturing together fragments. In a lot of ways, I am playing with this idea of improvisation. When most physical traces of memory are lost, withheld, destroyed, how do you engage with material culture and spatial registers to re-imagine memories? In this case, a ritualistic improvisation and alchemy of sorts is the conjuring up of a lost family and social histories through fragments. When a trinity of spatial trauma dissembles, displaces, and disperses memories, how do we repatriate these narratives and objects?

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (b. 1985) is a photo-based artist, writer, and educator from East Palo Alto, CA based in Brooklyn, NY. She is a Studio Instructor at the Brooklyn Museum and a public school teacher working with court-involved youth in East New York. Her work enlists archival as well as archaeological traditions to explore collective memory and her family narratives through found images, material objects, original photography, and book arts.

No Instructions for Assembly will be exhibited at Real Art Ways (Hartford, Connecticut) from 11 July–6 October 2013.