Luke Boland – What we’ve Made

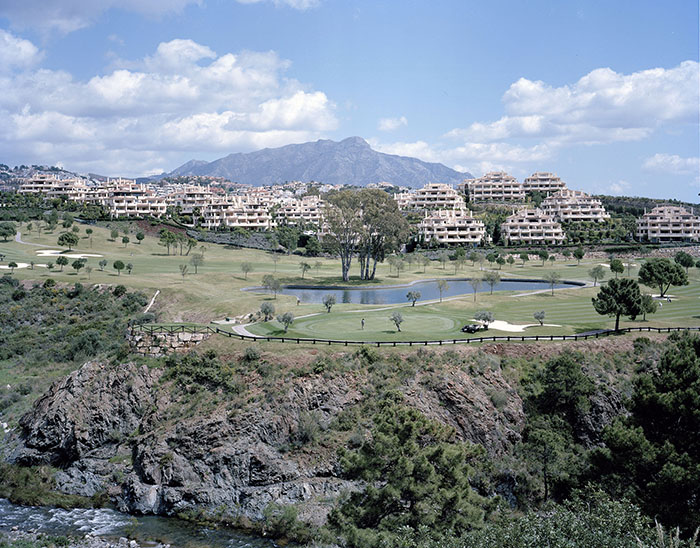

Singular figures amass the areas of manufactured confinement, once natural, now controlled through the maintenance of human beings. The locations vast in scale, oppressive of our mind-set, as we begin to live to keep the machine alive – demanding financial security and our lives as a result. The areas made up of a natural substance are overpopulated by the impact of our needs and our obsession with occupying land for our survival and leisure activities. While consuming areas, we overpopulate and smother the land that was once free to breath. It is given clamps to steady humans to the top of the cliff edge to smoothly glide down in a matter of minutes. Rocks half man-made and half natural support children and adults alike in the roadside entertainment as we look to escape our struggle to support, as our bodies gradually decline each day. Our bodies replenish, washing off the stress with the gentle pool of the rivers passing through the obstacles of rocks and ground.

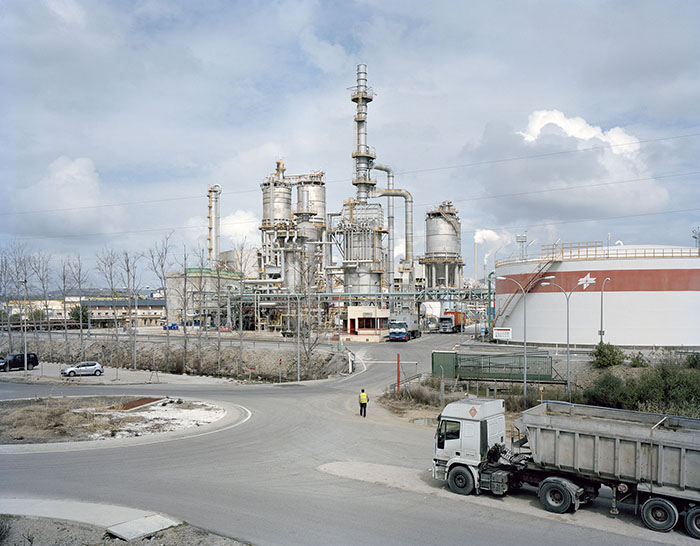

Our demand for living creates the infrastructure for factories, power plants and shipping yards, far larger in size than humans can comprehend – although we made them. What we’ve made dominates us, and all we can do is maintain and improve these behemoths as our living demands require more attention, as our ‘progression’ makes leaps forward. A sense of going sideways, instead of forward, sometimes comes to mind when debating technology’s influence upon our living, and to comprehend the possibility that we could not have access to someone from another country is incomprehensible. We have been spoilt, richly helped by the technologies we have surrounded ourselves in – so much so that if they fail, we fall. The world has adapted to technology, thus getting rid of our older ways, as the internet becomes our main form of communication to people we have never met. If it collapses, what will we do? If the power stations fail, we are left powerless until we fix them, so we must maintain and anticipate any issues, thus demanding our whole attention. The mind always wanders to the scene in 2001, when the technology onboard outwits its users, thus eventually destroying the people who look to destroy it. It almost took the form of a human as we see in HAL 9000 our primal instinct to survive and do anything to continue living.

The minor shifts between power and leisure seem to battle with each other in Luke Boland’s photographs, as the singular figure – previously mentioned – becomes over-dominated in scenes of horrific beauty. It is horrific in the sense of the grand scale of these objects demanding areas of Spain, Hong Kong, and throughout the world. People never stand a chance in his depictions, working almost as slaves and comfortably balancing in the crux of the pictures. The work becomes about scale and the notion of a window into the scene seen before his eyes as he shoots. Although the images portray realism, they are obsessed with the photographic depiction, using framing to such an affect we begin to see his idea progression as we look at each image. Unlike the work that associates with these topics of discussion, the work suggests a gentle question; the pictures quiet and calm even when the pleasant panic of leisure takes up the frame.

The central figure appears in every picture, sitting amongst technological giants. Formally this creates an idea and pushes the notion of man’s relation to the things we make, reflecting on how we deal with the monstrous size and burden this has put upon us. The pressures to keep them going, keeping them alive, for if they die, we are left in peril. If the leisure industries collapse, so does our entertainment. The mass corporate need for survival and eventual greed will eventually put a strain on our general living. Our sole purpose will be to keep these places alive, maintain and develop them as our need to keep occupied becomes stronger, and our needs become far greater than what we can deliver physically, mentally and intellectually.