Publishers series: an interview with Kodoji Press

…but I think that, in art, you shouldn’t think too much about money, as then it makes no sense anymore.

Since 2007, Baden-based Kodoji Press has been run entirely by award-winning designer Winfried Heininger. Though he sees it as much more than himself, talking of his practice as a collaboration and a negotiation between himself, the artists, and the concepts underlying their projects.

Over the past decade Kodoji has built up its strong reputation through a focus on non-commercial work and a dedication to promoting young, unknown, and up-and-coming photographers.

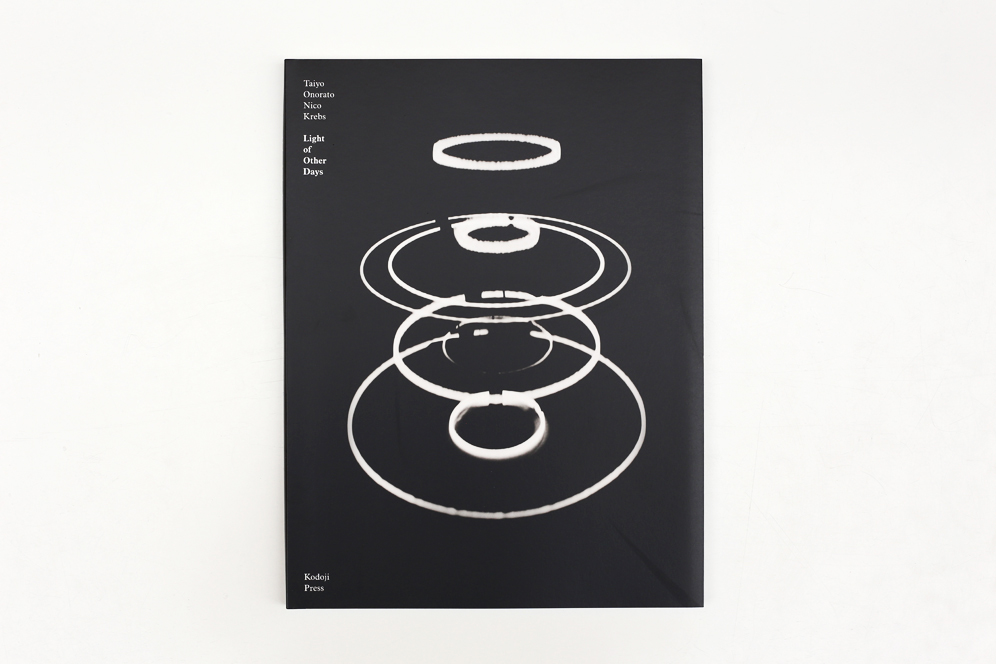

Published artists include Erik Steinbrecher, Taisuke Koyama, Anika Schwarzlose, Sandra Kühne, Melanie Bonajo, Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2017 shortlisted artists Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, as well as Jules Spinatsch amongst many more.

I joined Heininger at this year’s edition of Offprint publishers’ fair – held annually at the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, London since 2015 — where we took time to talk about what drives his publishing business.

You started out as a designer, so how did you make the move into publishing?

It wasn’t really a move, I’ve always worked in various fields of design; I did graphic design, I even did clothes design, but at the end of the 1990s I opened a bookstore with a colleague next to my design studio in Cologne, my hometown. At that time art book fairs didn’t exist, so our idea was that we’d go out into the world to show our books at regular art fairs, to have a stand there and to introduce people to European publications. I met many people and artists started to ask me if I’d design and publish books for them. It was different back then, there was a real need for publishers. In 2007 I stopped running the bookstore and I thought, ‘OK, I will go on and publish something’.

For me, there must always be a reason behind what I do, and the reason for moving into publishing was that I wanted to offer a communicative platform for non-commercial projects to young artists who had never published a book before. Design is my profession and passion and to become a publisher it was simply a logical consequence to combine all my interests.

How do you choose the artists you work with and what is it about their work you think is really worth showing?

It’s not so much about their work, it’s more that I’m into the people. I take it very personally. I’m interested in and I love people; I love different people – with different opinions and struggles. It’s about building a relationship with the artist – I need to find a connection, I don’t like to see this as a business. That’s maybe why I am struggling financially, but I think that, in art, you shouldn’t think too much about money, as then it makes no sense anymore. Ideally I work in close collaboration with the artists to develop their book project out of their artistic vision and intention. In fact I deeply like the nature of collaboration. Everybody comes with his own knowledge, his luggage and connections. You don’t know where you end and somebody else starts.

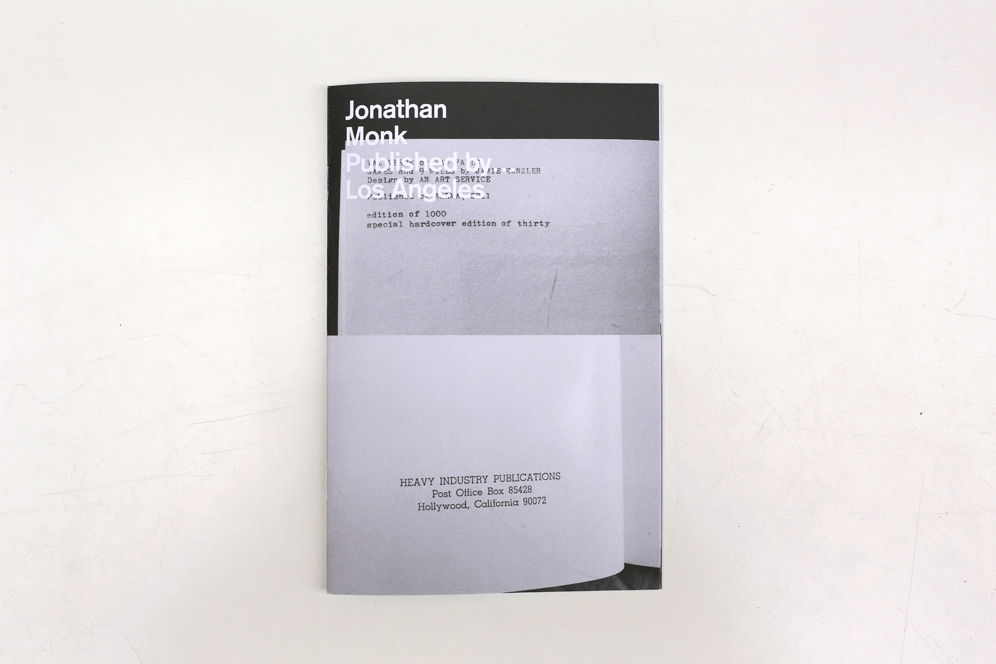

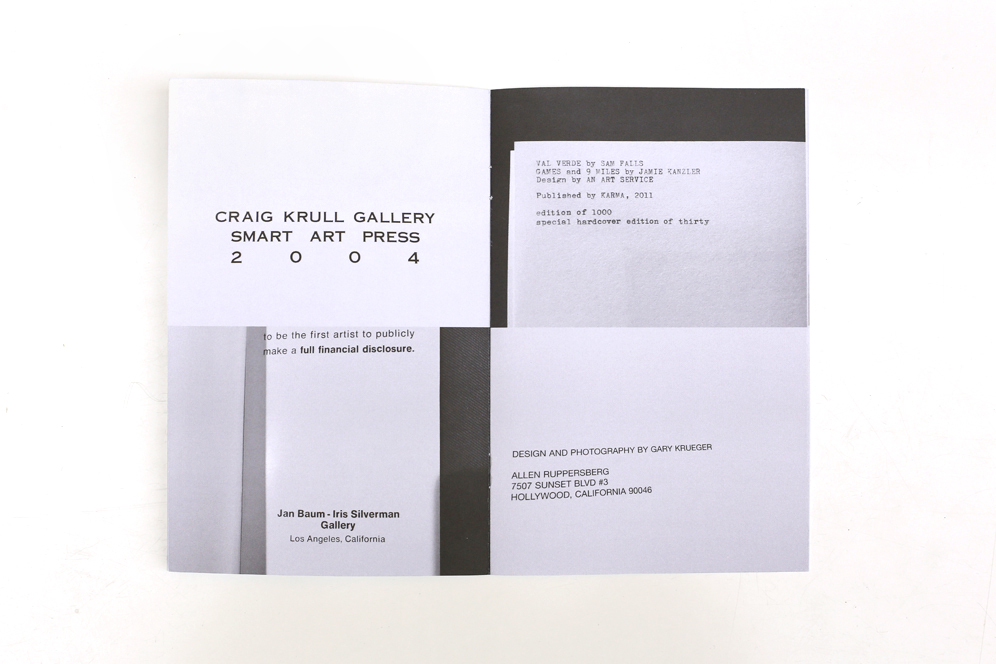

PUBLISHED BY…LOS ANGELES by Jonathan Monk, Kodoji Press, 2017

Kodoji doesn’t have a single aesthetic that it sticks to, there’s a huge variety in design, techniques, and materials, as well as projects. Is this the result of you working closely with the artist?

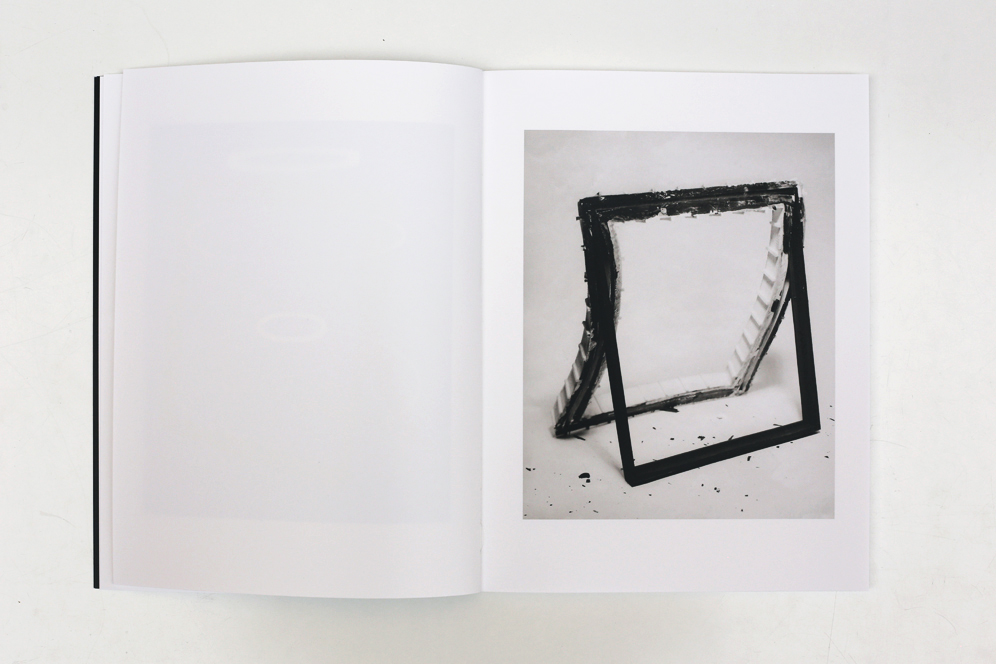

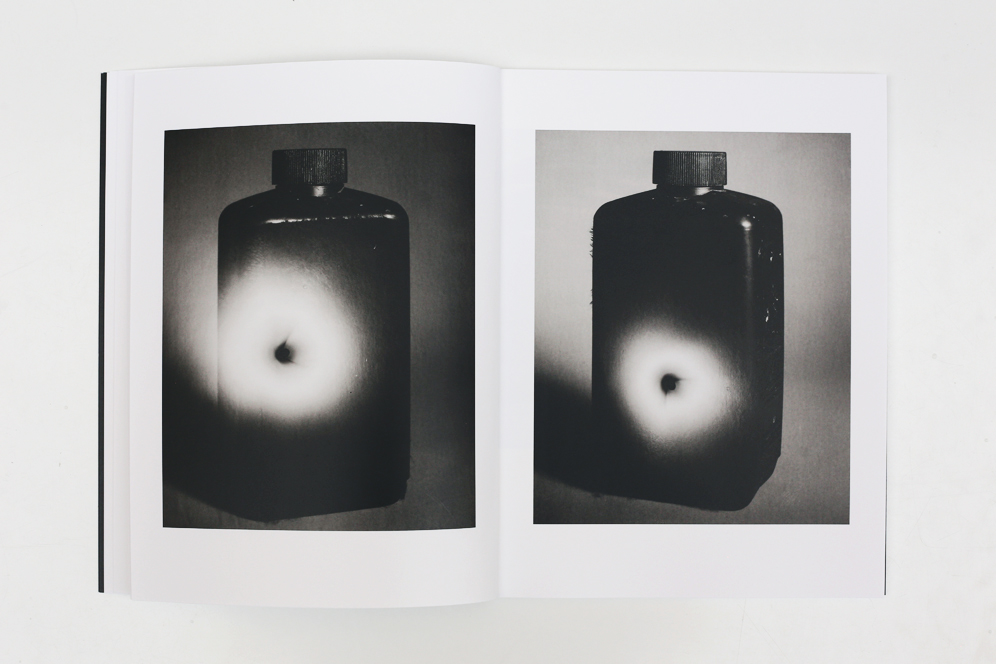

Sometimes, and sometimes not. I always ask the artist to write me a statement or we have an intense talk about the work itself. For me, everything follows the intention of the work, I start from this and transform the work into a book, or into something between book covers. There is always a unique concept needed. That’s why, in my opinion, not every book look the same; there’s sometimes a leporello fold or an accordion fold needed, in other cases you only need a little zine, and at times you need a hardcover book.

So there’s always a certain treatment related to the intention of the work. The collaboration starts when I review the artist’s selection or editing of their project based on the statement they’ve given me. Then sometimes my selection turns out to be different. When the artists says, ‘this is my most important picture, it needs to be in’, then I can say, ‘ah, look at what you wrote or what you said – is this really a part of it?’, so we can start to negotiate and develop concepts and ideas around what the book should look like in the end – for me it’s a collaboration.

Could you talk a little about some concepts you’ve found particularly interesting?

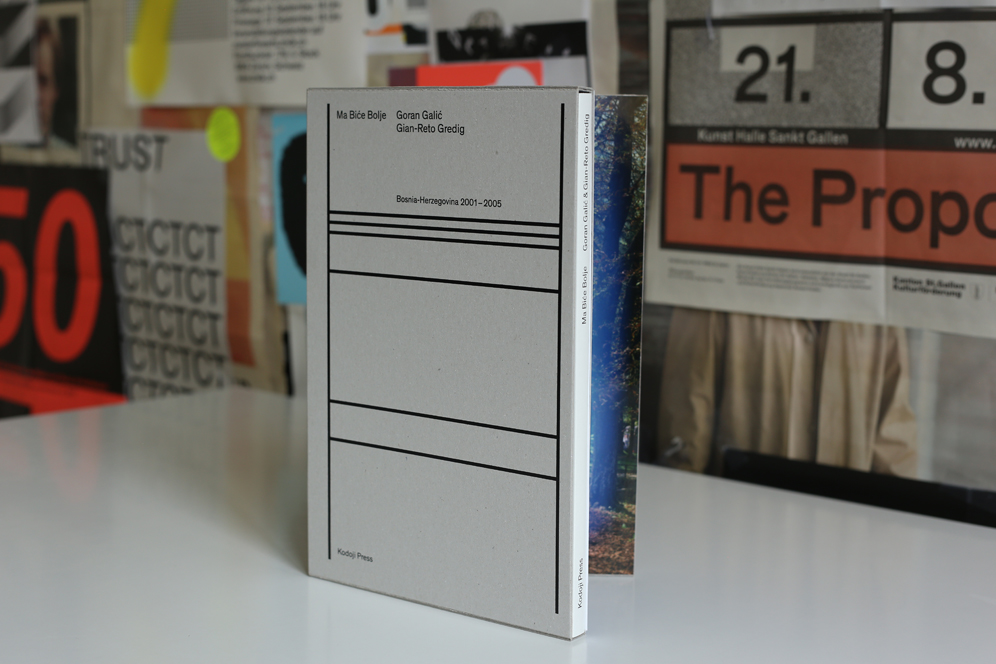

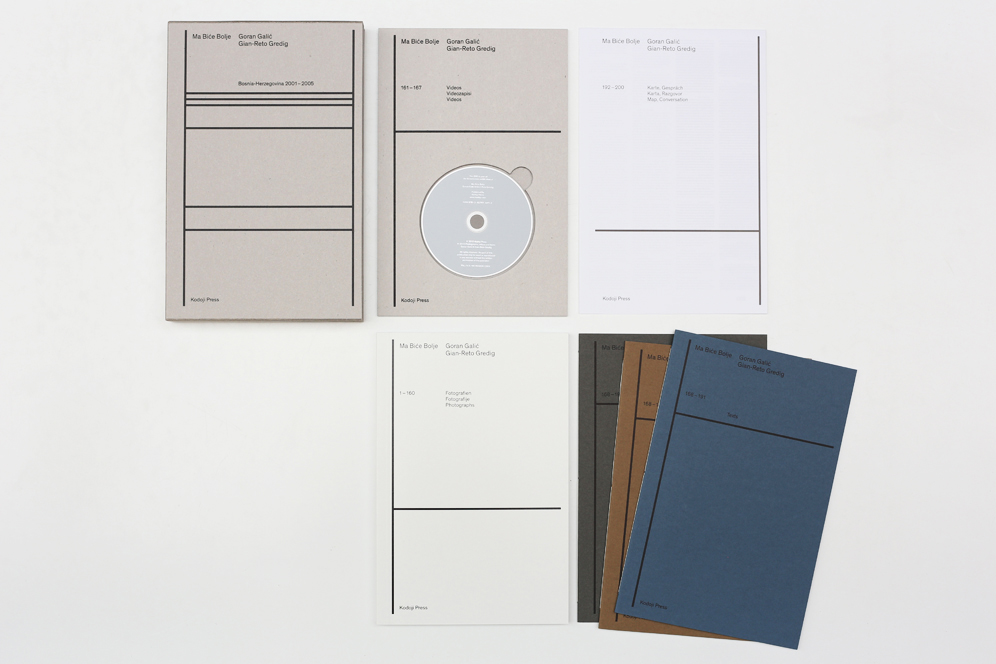

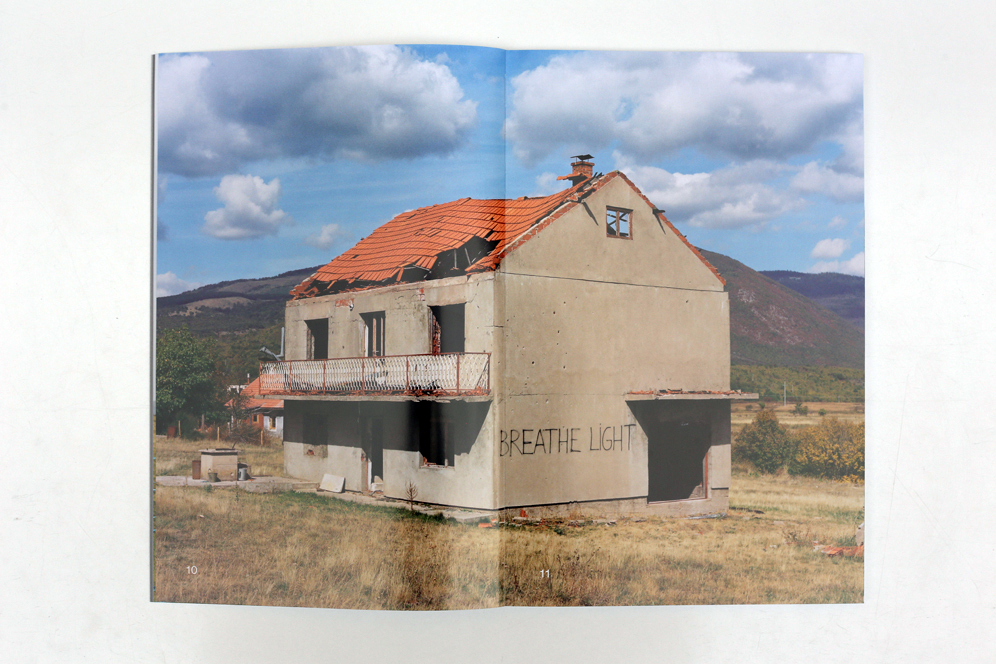

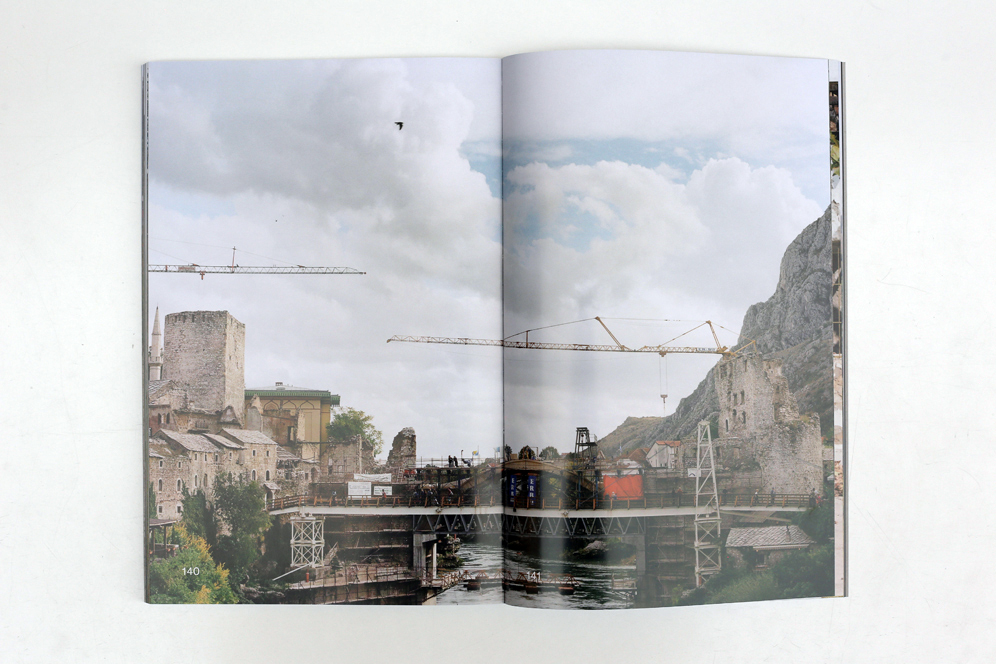

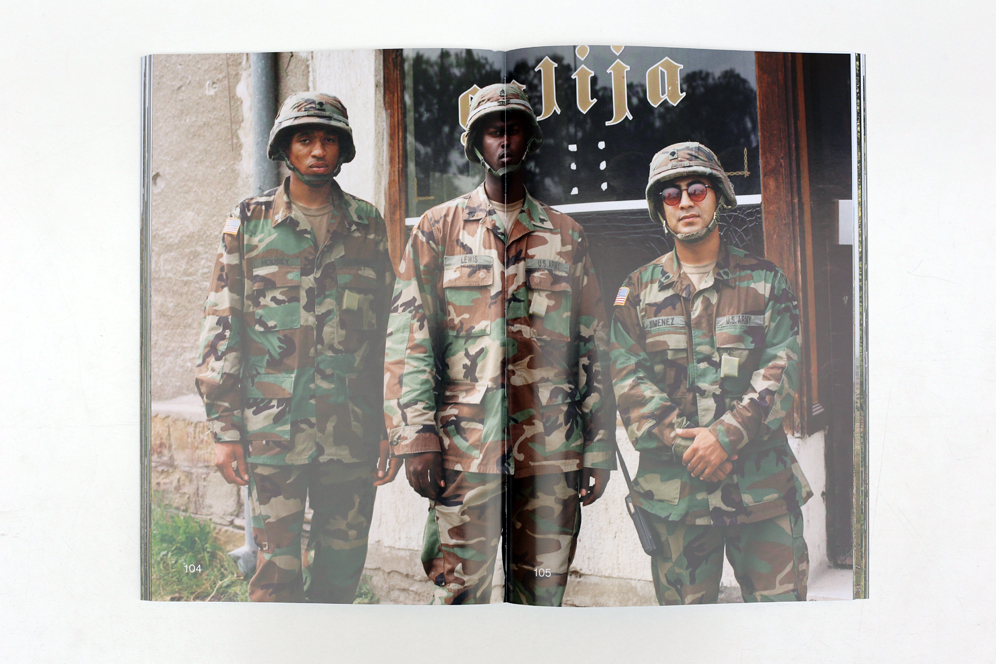

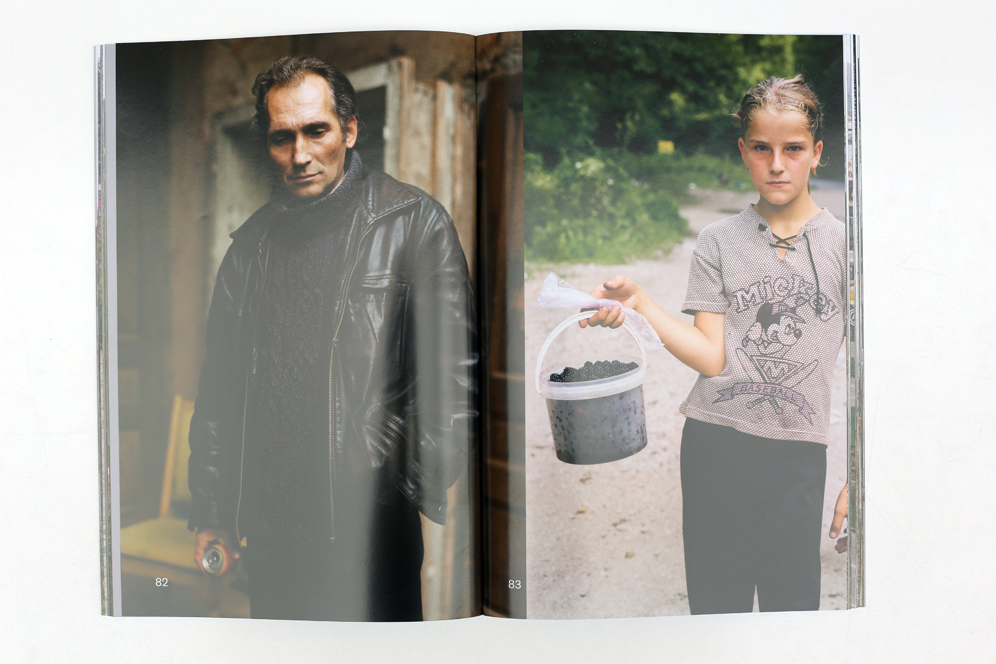

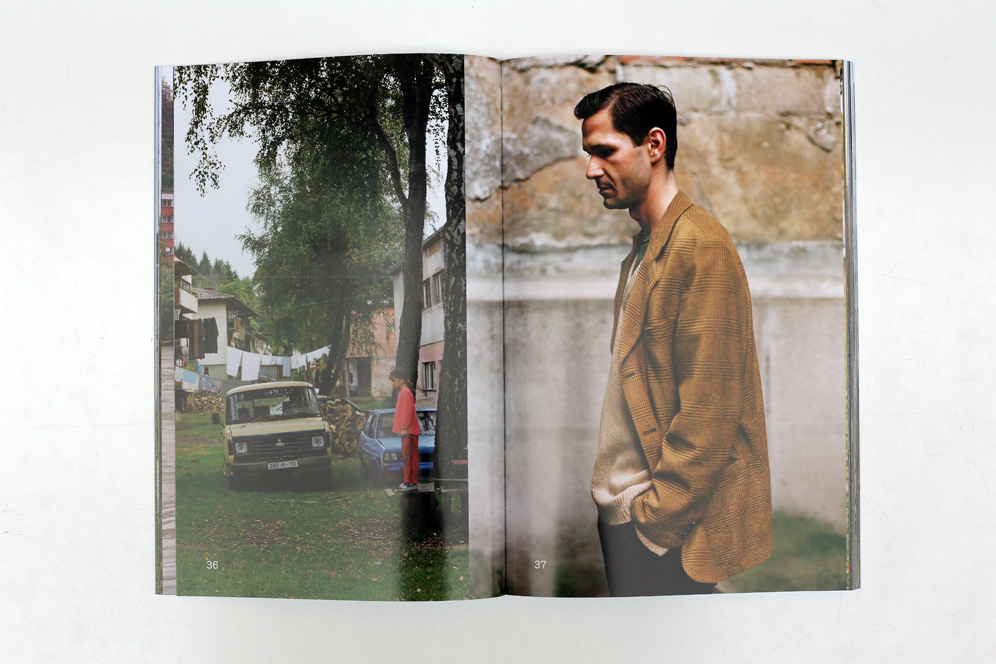

There’s Ma Biće Bolje, a six volume book by Goran Galić and Gian-Reto Gredig, they’re both Swiss but Goran has a Bosnian background. The meaning is, “it’ll get better”. During the war in Bosnia Goran often heard this expression from his father. It would once be commonly heard in the former Yugoslavia, but it is a rarely expressed sentiment today. During the artists’ studies, they started to explore, film, and photograph Bosnia, to better understand the recent conflict in the country Goran’s parents had left for Switzerland. Their work studies how documentary and history are constructed through photographs, short essays they wrote, and also films. By perusing the different media the reader encounters different facets of the same stories. The final element of the six volumes is a map tracing the country, identifying only the roads travelled by the pair in search of these images and narratives, with annotations of where their material was gathered. The people who buy the book can really find out how everything is related. All six elements fill a double-winged slipcase opening to display a single image which suggests, at first glance, that a brighter future is to come. I thought that romantic picture would be the right expression for, “it’ll get better”, but at the same time it is very ambiguous. It shows a sign by the road saying you have to stay on the track because of landmines. That’s how it still is today. They have always shown this work together; mixed up in exhibitions, and I wanted the concept of the book to express the same.

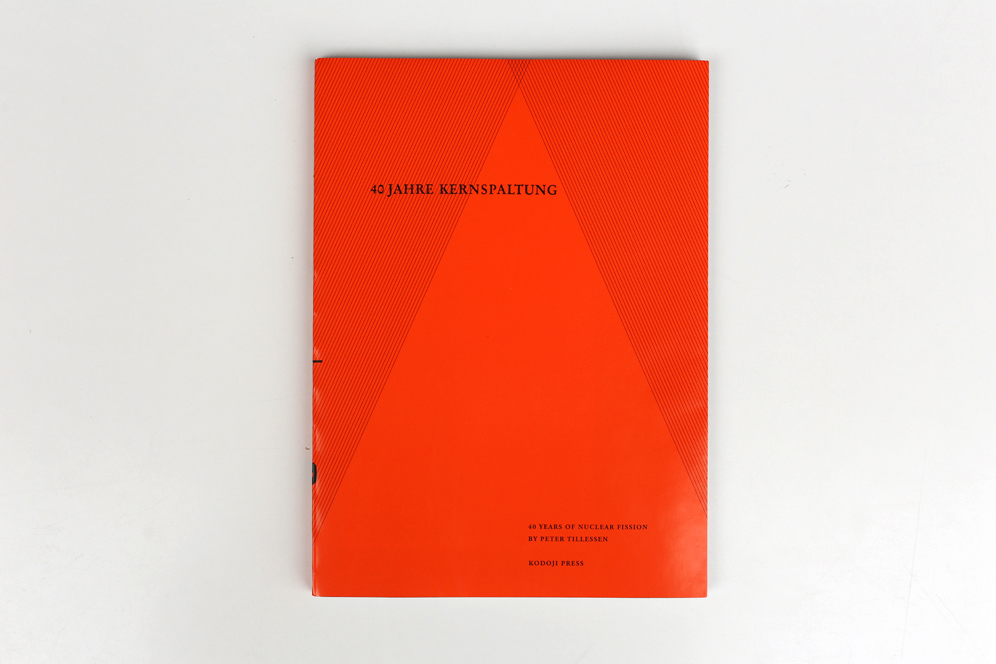

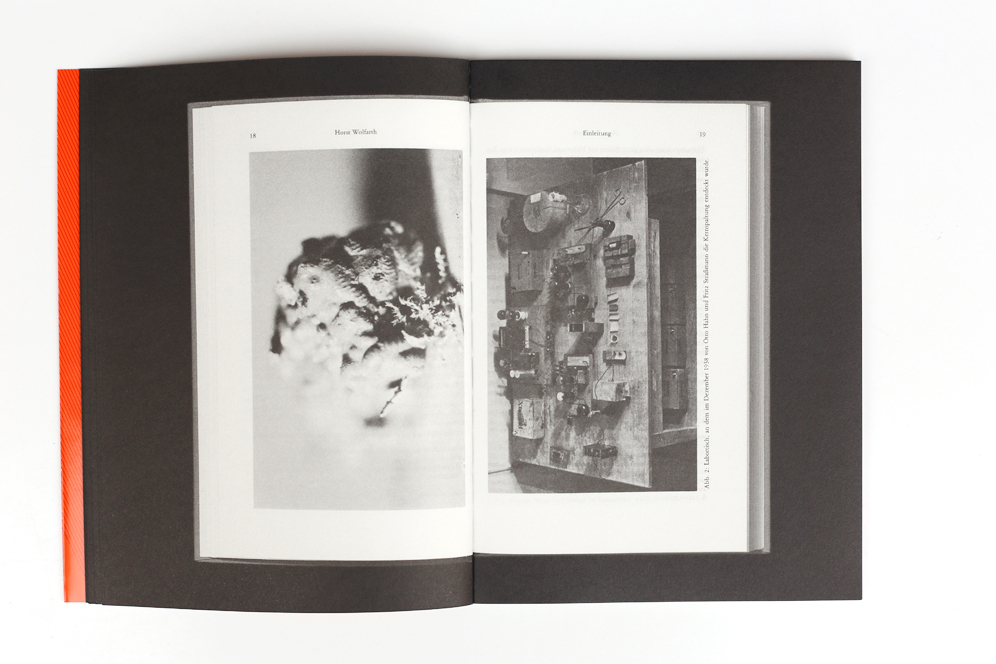

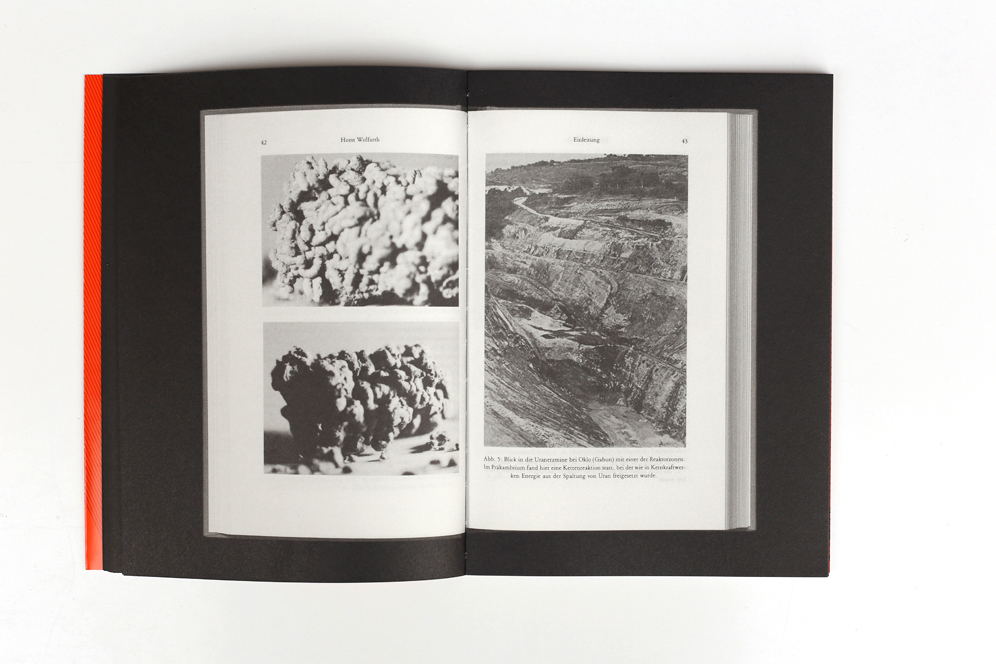

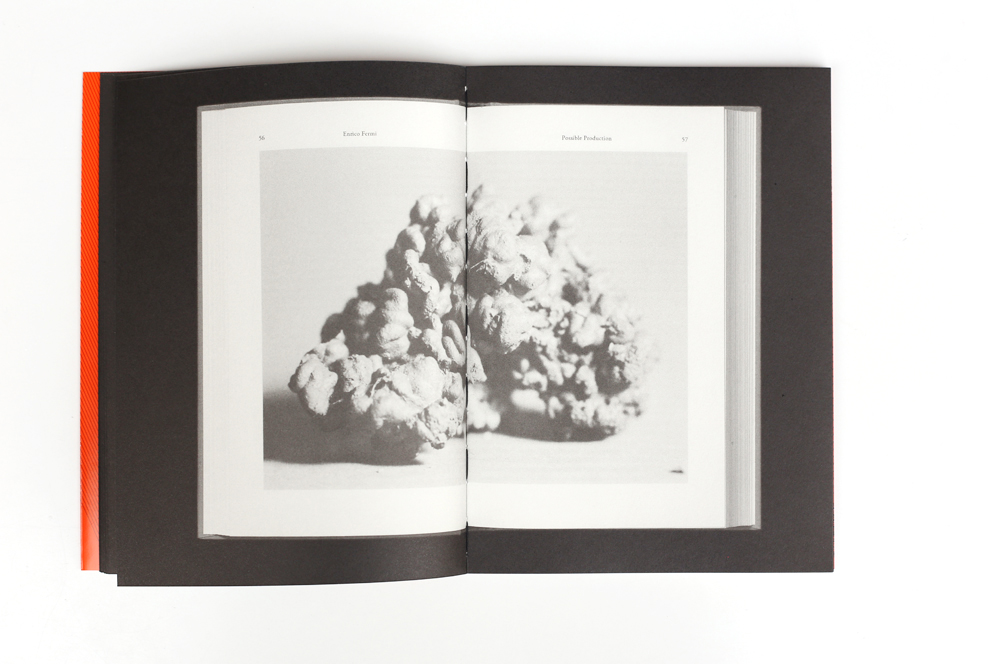

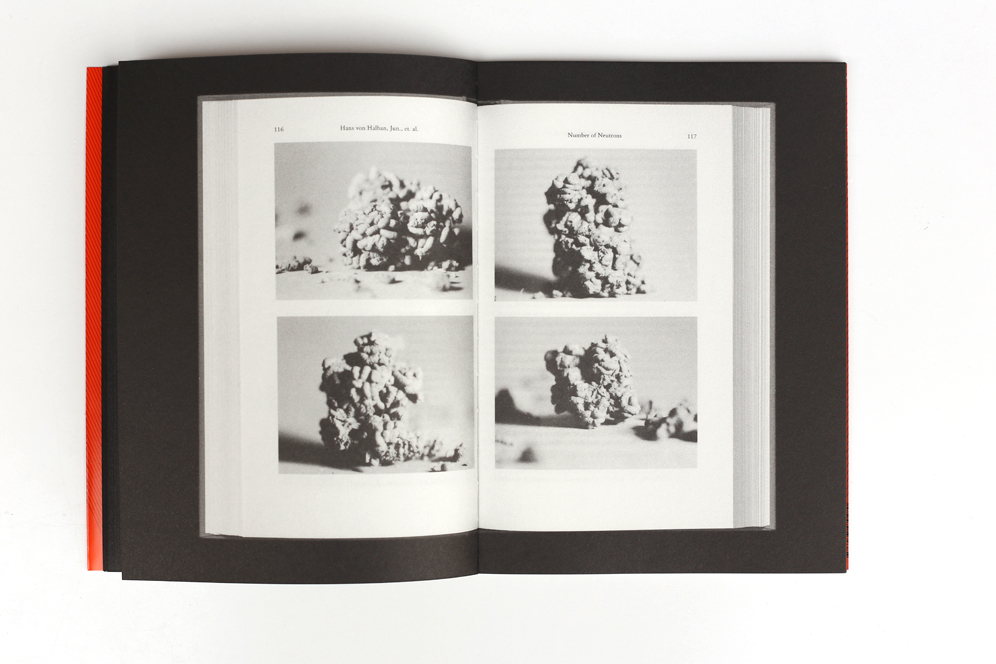

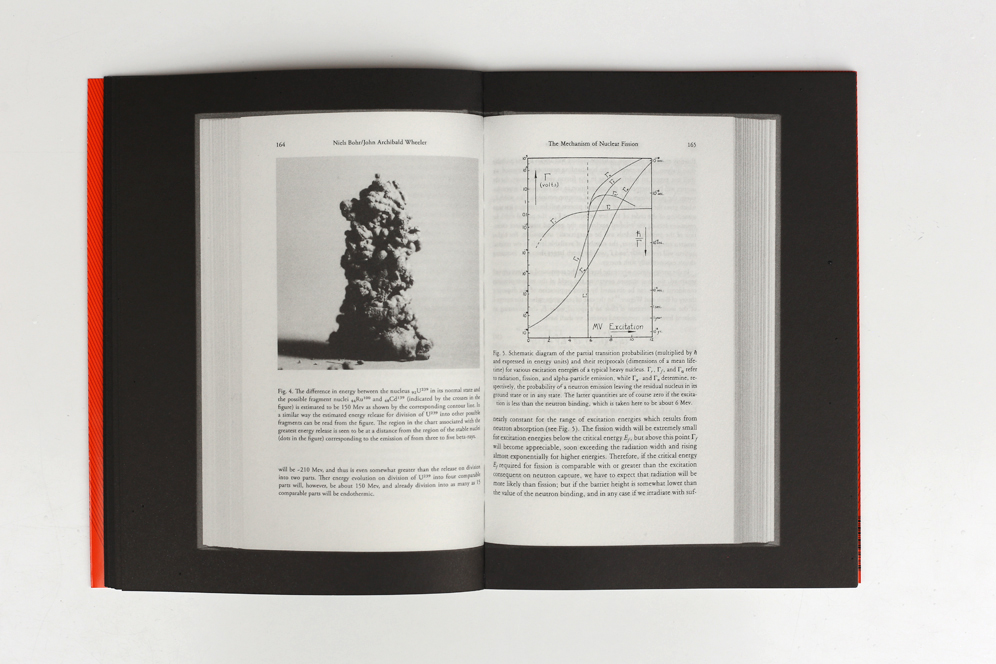

Another example is 40 Jahre Kernspaltung (40 Years of Nuclear Fission), by Peter Tillessen. I knew that his father was working for the nuclear industry, when I was visiting his studio I was always looking at a book called 40 Years of Nuclear Fission and I was attracted to its cover and content. Once, I went into his studio and he had hung up 40 silver gelatine prints of worm shit. They actually looked really nice and I put them together in my head with his father and the nuclear fission book. I asked him, can we somehow put this all together by physically changing the original book and to publish a book that combines all of these elements but looks like the reprint of the old book?

The reason he made those 40 prints was that he lost a bet to his best friend; Peter had only one child by the time he was 40, and his friend had three, that’s why he ended up making 40 artworks. Inspired by the idea that Darwin wrote about worms and how important they are for the soil and the earth, he then collected the worm shit in a cemetery in Zurich. Another idea was to ask him to write an essay about the bet, himself and the relation to his father. He had the idea to add to the book also pages from Darwin’s essays. It’s an eclectic concept, but one put together in 5 minutes. First the artist himself struggled a lot with it to find his approach, but it turned out very nice.

Everyone comes with their own knowledge and own history, I think there’s never two people who understand or anticipate the book in the same way, and that’s interesting to me

How do you balance getting the artists’ work out there with non-commercial projects and the needs of running a publishing company?

It’s not easy to balance, but it’s important that you help someone to bring something out. I try to find money for producing younger artists’ work through foundations, or we sell special editions. I’ve thought about starting to mix my program up with well known artists, because some have asked me to publish some of their work as they appreciate the quality of what I do. It would also make it more competitive for younger artists, which could create an opportunity.

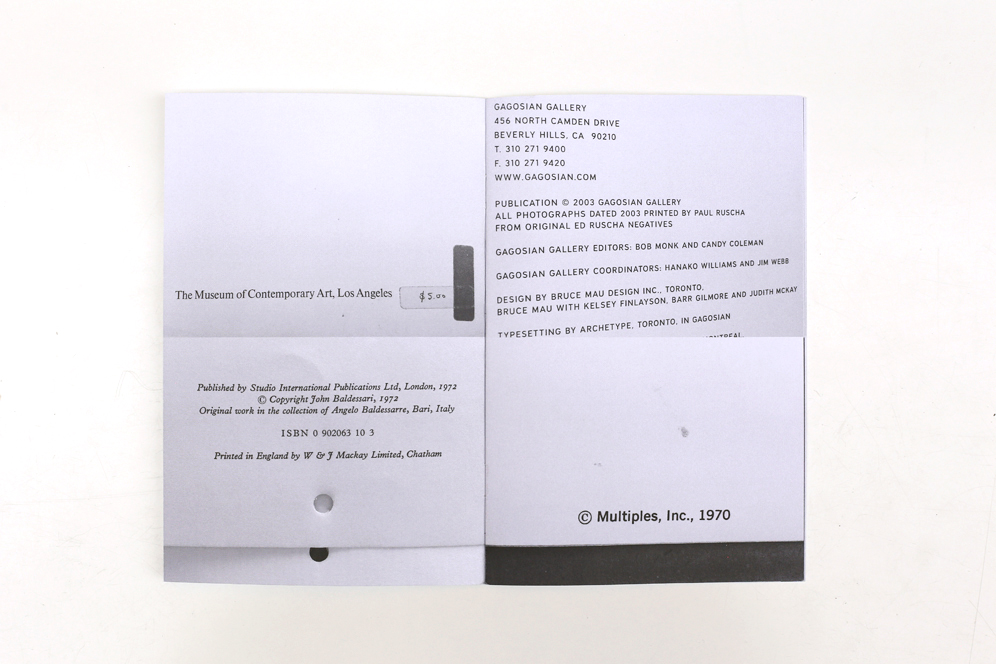

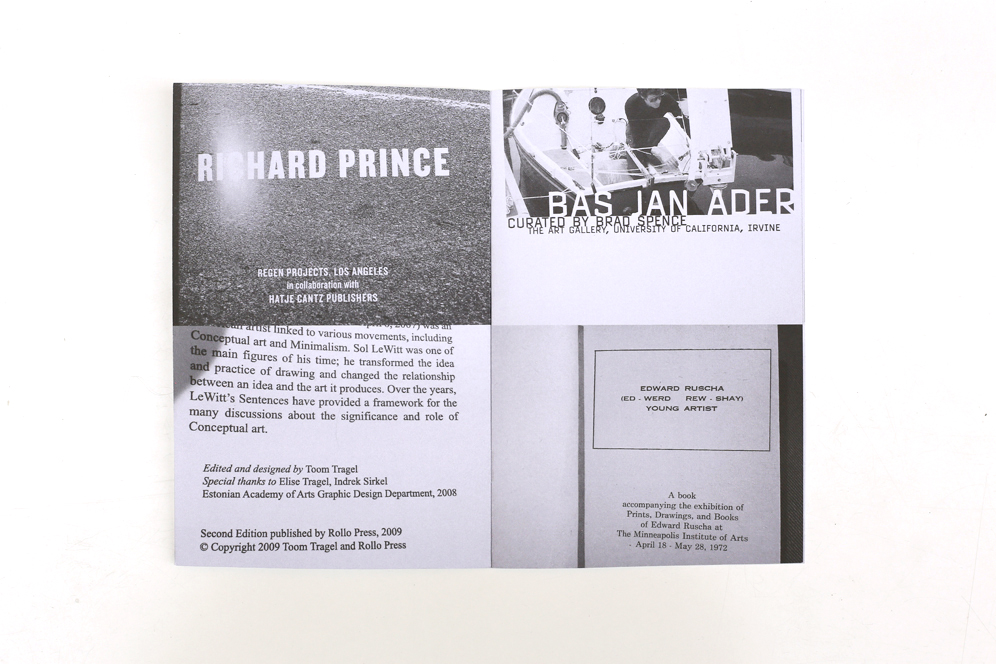

Recently, I did a zine for Jonathan Monk which is interesting and we’re excited about it. Initially his idea was to co-publish a book with hundreds of different publishers—each one an equal part of the project… a book made up of colophons, different fonts, designers, distributors etc. Brilliant, but logistically impossible. We’re now starting a series of zines called Published by… LA was the first edition for the LA Art Book Fair, the second one will be for New York followed swiftly by London, Paris and so. Jonathan, as an avid collector of artist books, has tried to curate his shelves into sections or individual cities. Artist, museum or publisher create the selective process.

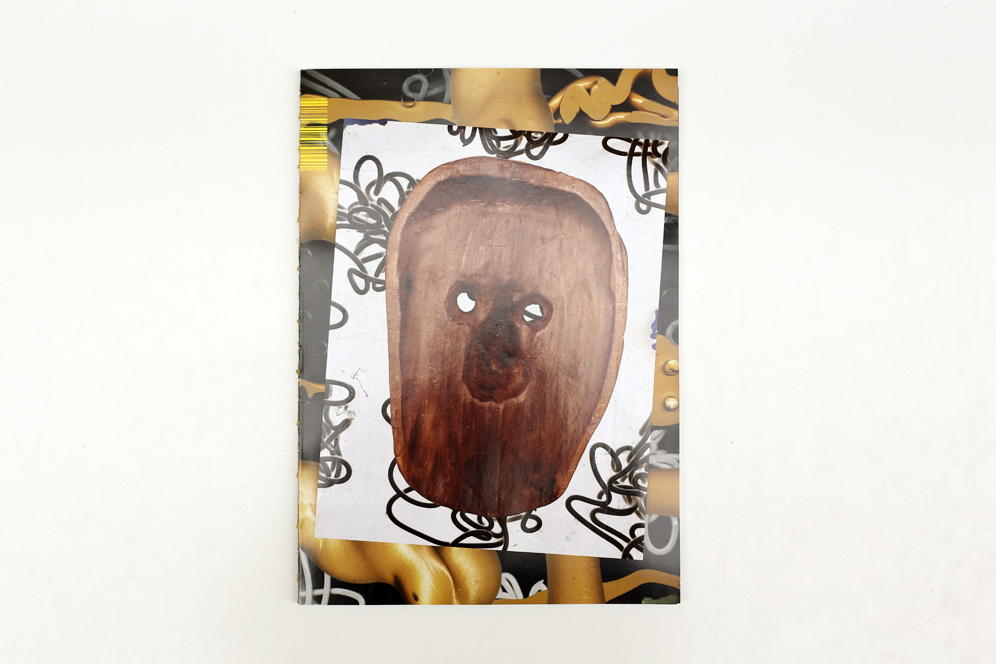

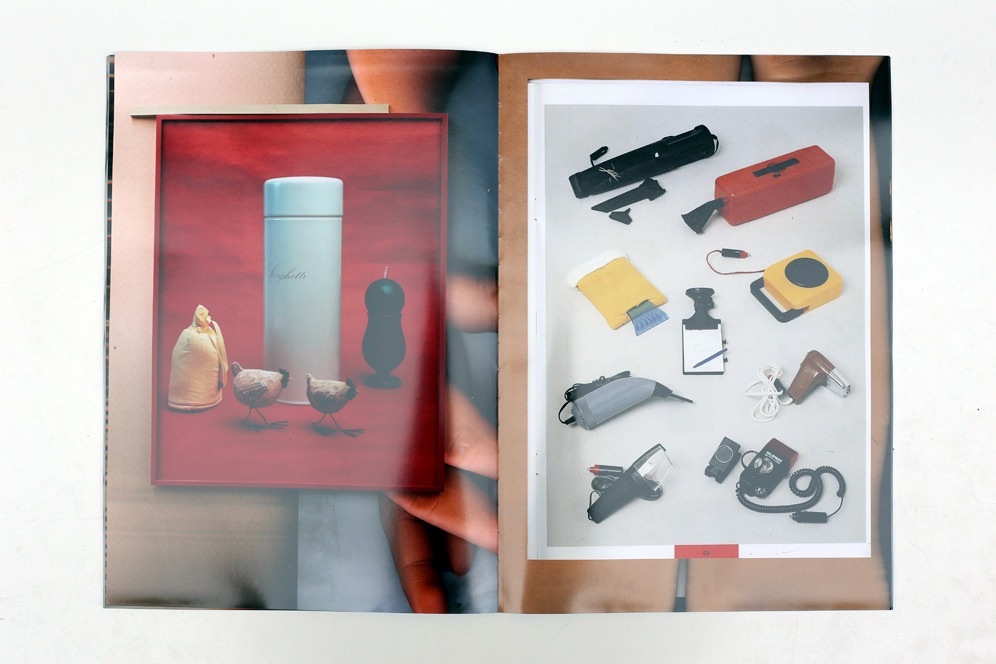

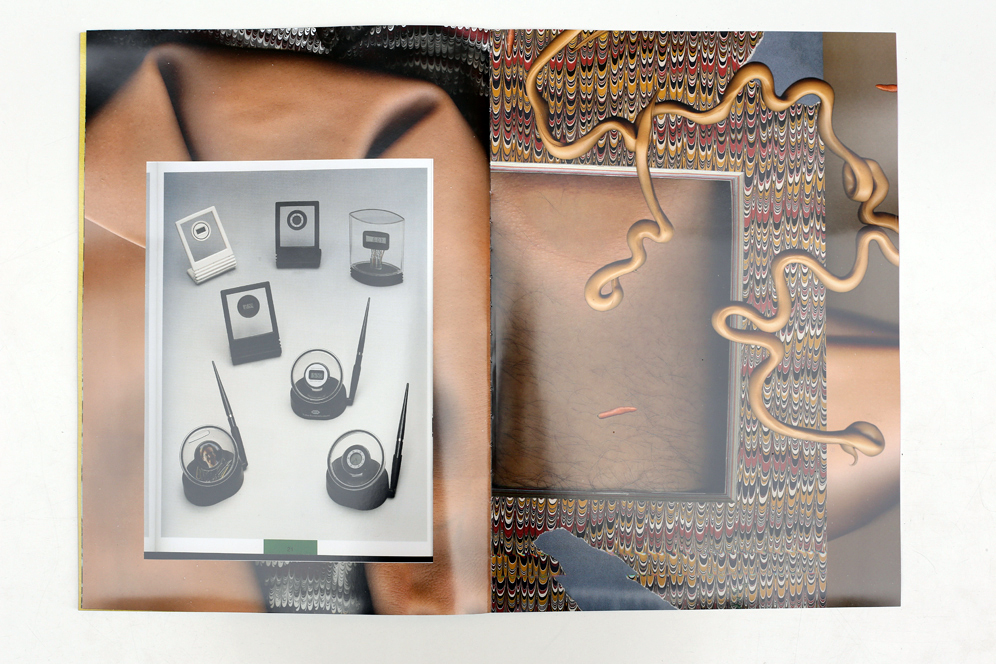

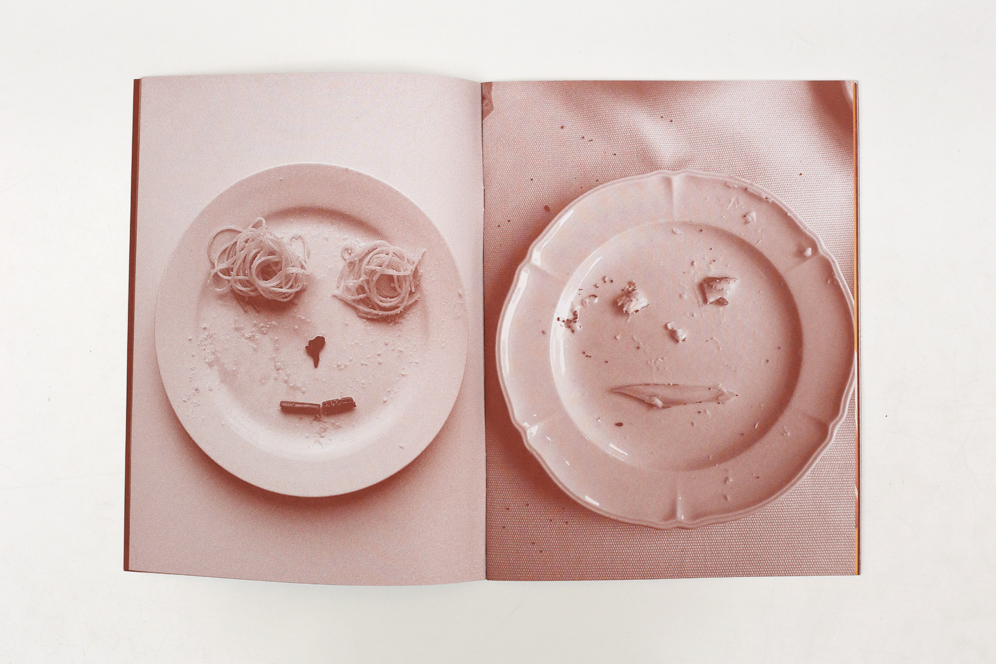

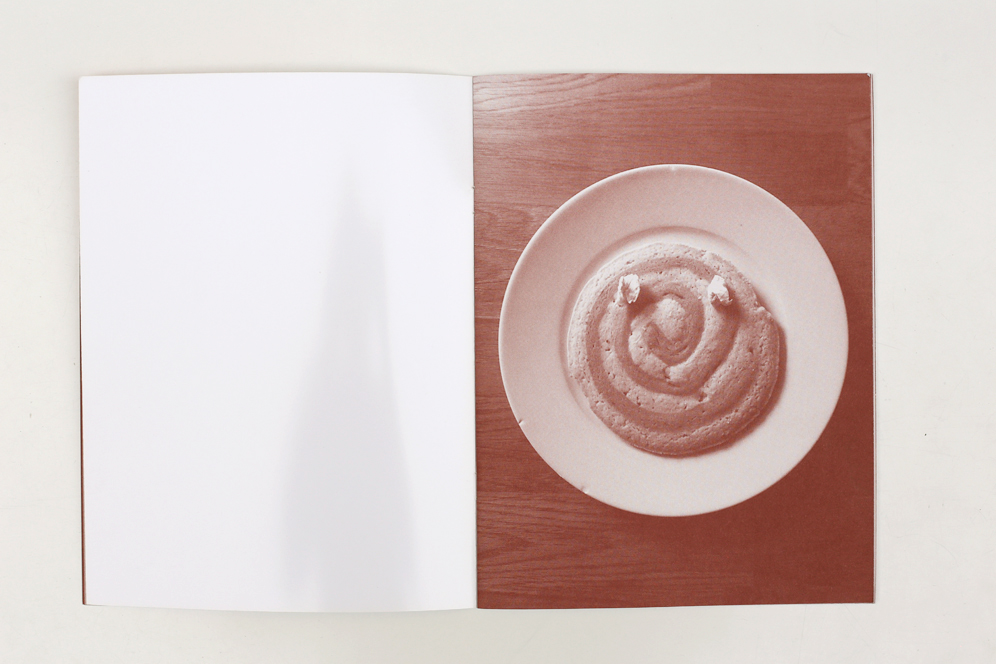

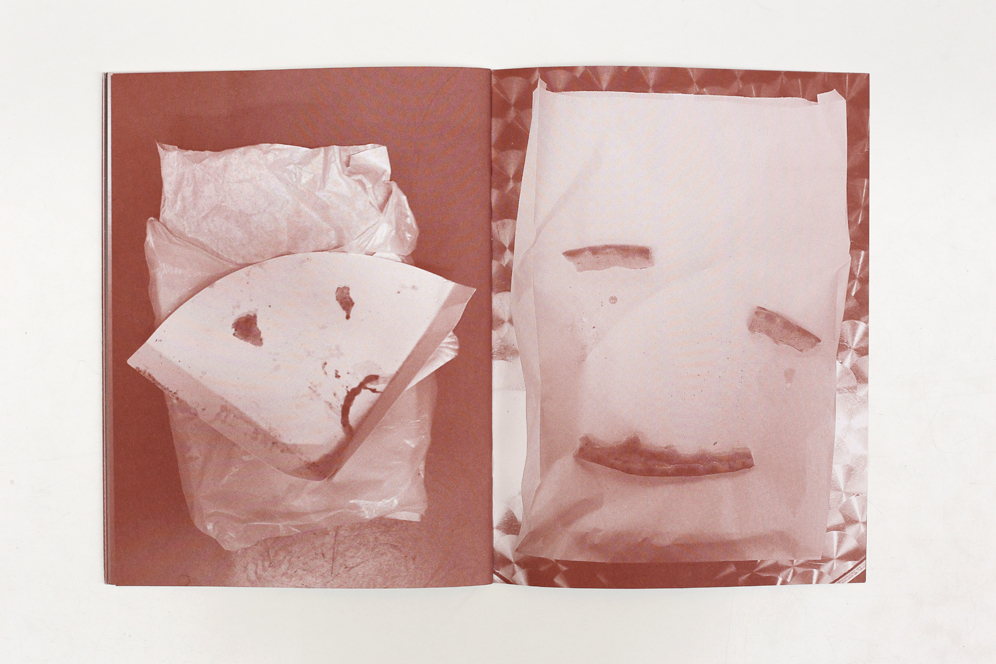

THE POMMEL HORSE POPO by Stefan Burger, Kodoji Press, 2013

You’re very prolific, you put out a book every one or two months. What do you find difficult about the process, but also what do you learn with each release?

It’s difficult to say, what I like in my life is to learn something everyday. That’s really a need, that’s why I need to see everything, I need to understand everything. There’s lots of people I’m working with and it’s interesting, you dive into someone else’s intention and you learn something about the person as well as the outcome, the work itself, and then you need to transform this into a book; even if you think it’s a simple book, you’re always surprised because something happens and you learn something more. It could also only be about the technical aspect or the design. It’s really challenging, but I also enjoy being part of this, it’s vital to me.

When someone comes to the fair, they pick up a book, they buy the book, what do you want them to feel when they’re looking and reading through it?

I’ve never thought about that. Everyone comes with their own knowledge and own history, I think there’s never two people who understand or anticipate the book in the same way, and that’s interesting to me. When people talk to me about what they like in the book or the artists’ work it’s always different. I always learn something because it’s so fun to hear from other people their interpretation from their own perspective. So I’ve never thought about this, I try not to because it keeps me open, otherwise these concerns may turn up when you’re working on a book, and then you might go down a road which isn’t your own.

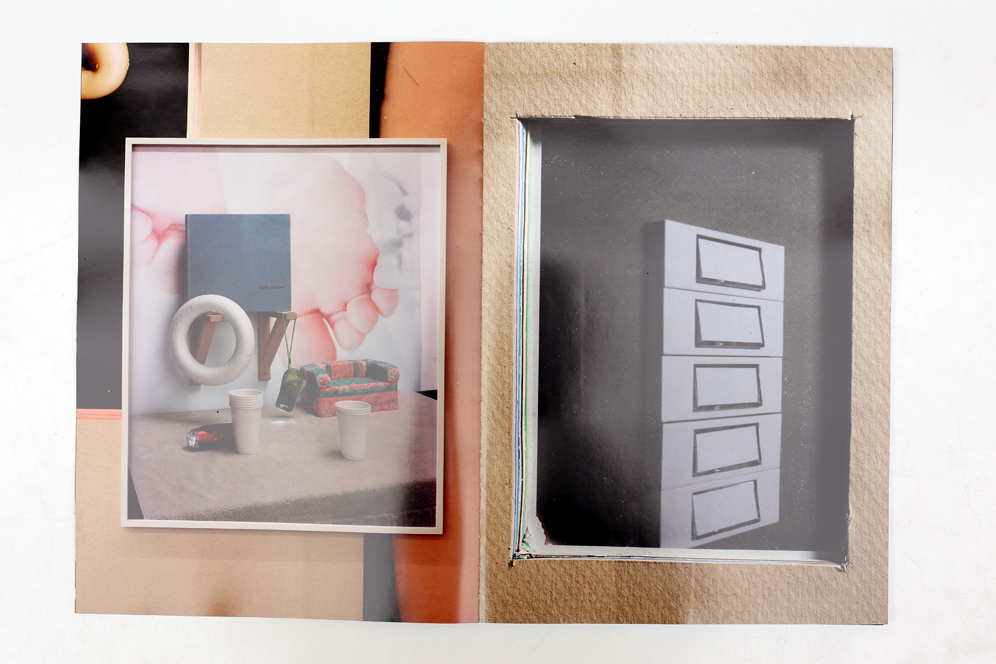

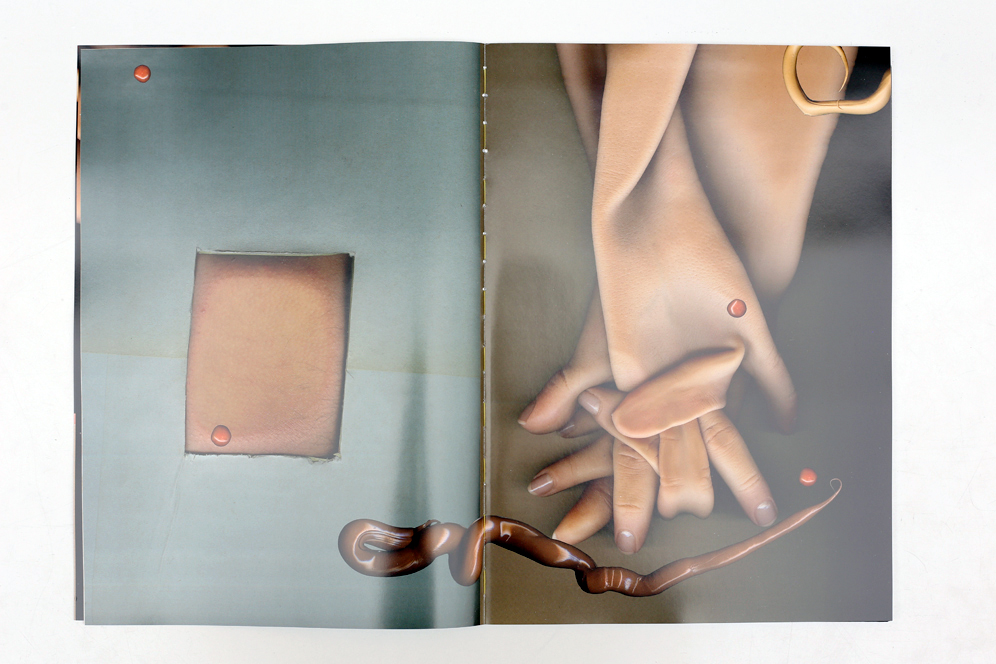

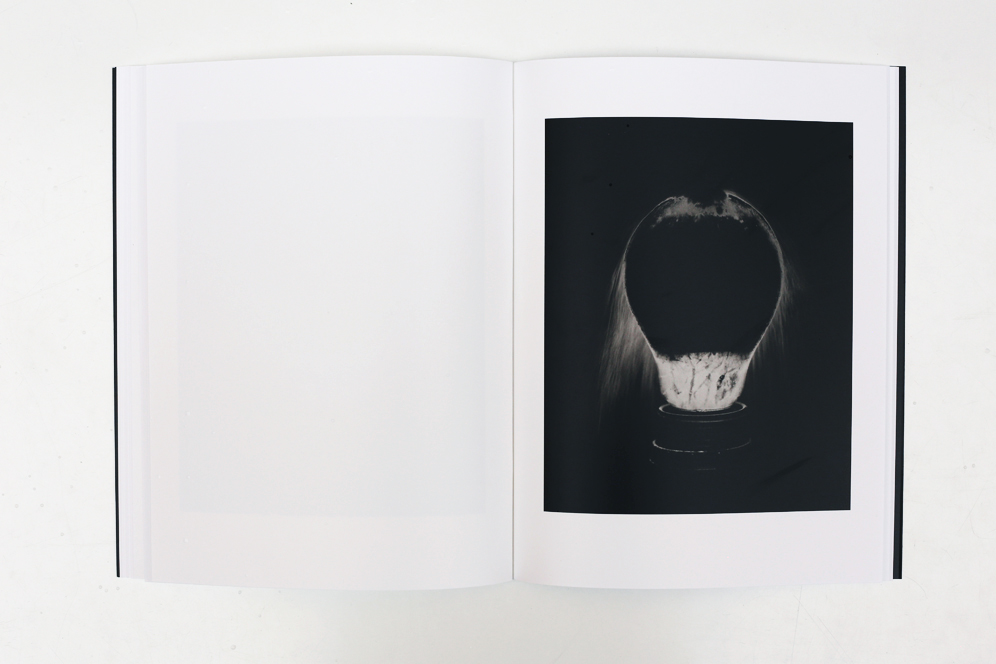

LIGHT OF OTHER DAYS by Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Kodoji Press, 2013

Are there any particular publishers that you’re excited by?

I really like Roma Publications, Dashwood Books, and Arnaud Desjardin at The Everyday Press makes totally unique artists books; he finds fascinating work that’s completely outside of photography.

Finally, where did the name ‘Kodoji’ come from?

In 2003, when I still had the bookstore, we were invited to give a lecture in Japan, and later on we have been invited and went to Golden Gai, the old night quarter of Tokyo. So we went into this bar, and I thought something was odd because there were pictures by Daido Moriyama hanging everywhere on the wall, and a bookshelf next to the restroom was filled with iconic books by famous Japanese artists. I learned that those artists, designers, and photographers frequently meet in this bar. The bar was called ‘Kodoji’ and it means, ‘a child of blunder’ or ‘small blunder’. The founder of the bar was Takeo Ono, an actor in the theatre, and I guess he was a child of blunder. He passed away in 2002, but his friends still run the bar today. I like the meaning of small blunder, because you only learn and live through mistakes, and there’s always a small blunder in every book. If not, then I put one in.

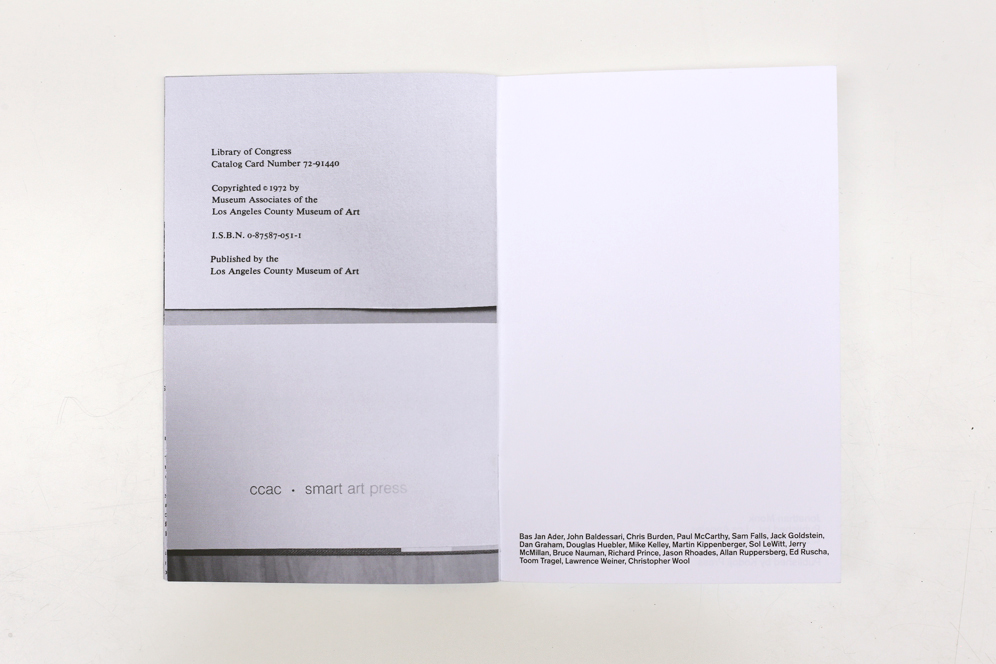

MA BIĆE BOLJE by Goran Galić & Gian-Reto Gredig, Kodoji Press, 2012

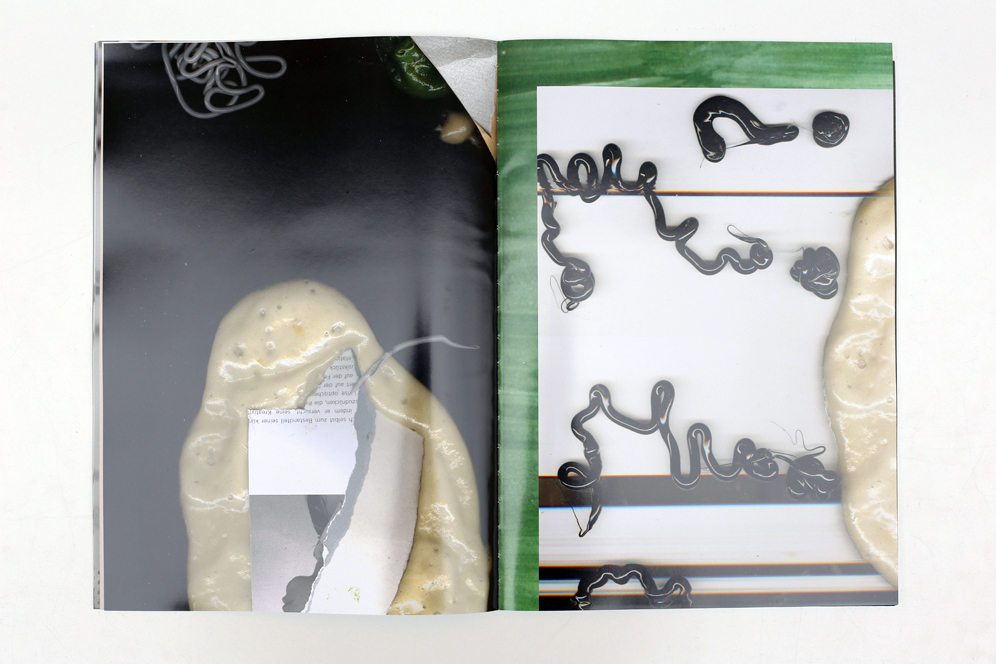

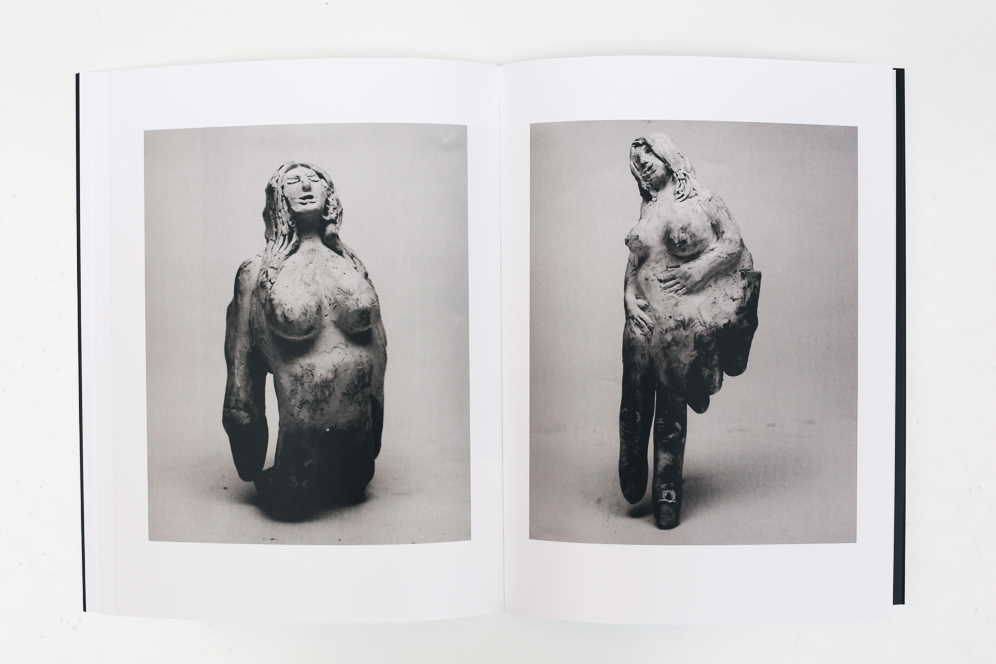

TROUBLE MIT DER ANIMA by Erik Steinbrecher, Kodoji Press, 2012

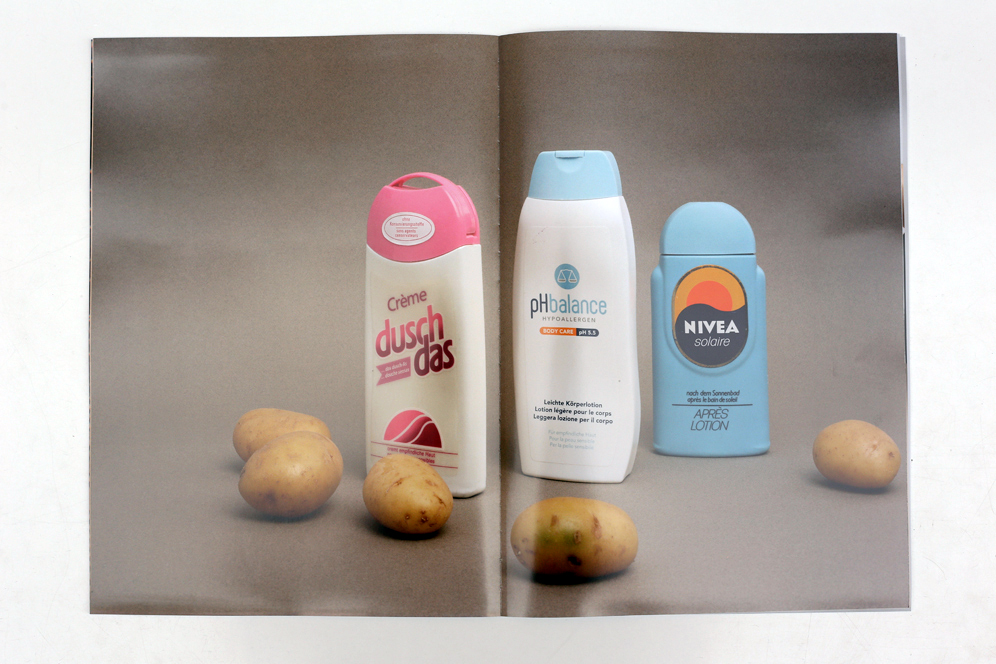

40 JAHRE KERNSPALTUNG – No. 3 by Peter Tillessen, Kodoji Press, 2012