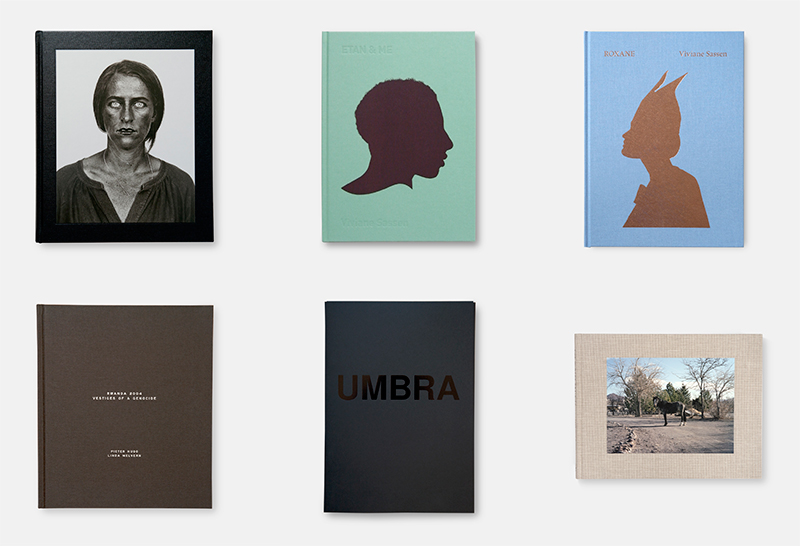

Publishers series: an interview with oodee

Damien Poulain’s studio is quite reflective of the way in which he has approached publishing; he sits in a large converted factory in the east end of London, surrounded by like-minded creatives who, as with Poulain, appear to be endlessly tiring over projects. Since starting oodee back in 2011, the book’s produced by Poulain have been the result of intriguing collaborations, ranging from working with young female photographers on their first books, to publications with established names such as Viviane Sassen and Pieter Hugo on objects that extend well beyond what we consider to be the traditional model for publishing photography.

How did you start with oodee?

I started in 2011 with the series POV Female. It began with an observation that there are few female photographers on the photography scene. The field has been historically dominated by men, however women have had an important contribution to photography since the beginning of it, but they have sadly been in the shadows. I thought it would be relevant to work on the female photography of today.

I guess that kind of answers my next question, what made you want to make the POV Female series?

POV female series is based on this observation. Still further I was surrounded by quite talented female friends that had accomplish their art school. They were all arguing about the difficulty of starting a career while also searching for role models in an industry with few females photographers — for those women, this fact become a certain vision of life where they are able to consider their path as difficult.

I find it interesting that you began with cities (London and Tokyo) that are quite steeped in their own histories of photography and then shifted to Beirut and Bogota which have, by comparison at least, much more marginal histories. Where did that transition come from?

Well London was obvious, I needed to start somewhere. I needed to see if the project could work. I used London as the trial for the project. Afterwards, I thought to create a photographic journey into opposites cultures. Moreover the geographic selection comes from my desire to attempt to cover all the continents. I wasn’t necessarily thinking of a city with a photographic background or specific history. The journey went from London to Tokyo, to Johannesburg, to Bogota and finally to Beirut. However, it was really important to make a selection of unexpected and controversial cities. I decided to focus on mysterious cities that are not under the spotlight. To take an example, Colombia is quite an emerging country in terms of its artistic scene. There’s something exciting about this city by its complex history and unknown photography. As Beirut and Johannesburg they were forbidden places for a long period and it was a challenge to give a view of those cities today. At the end, it generates more strength to the project.

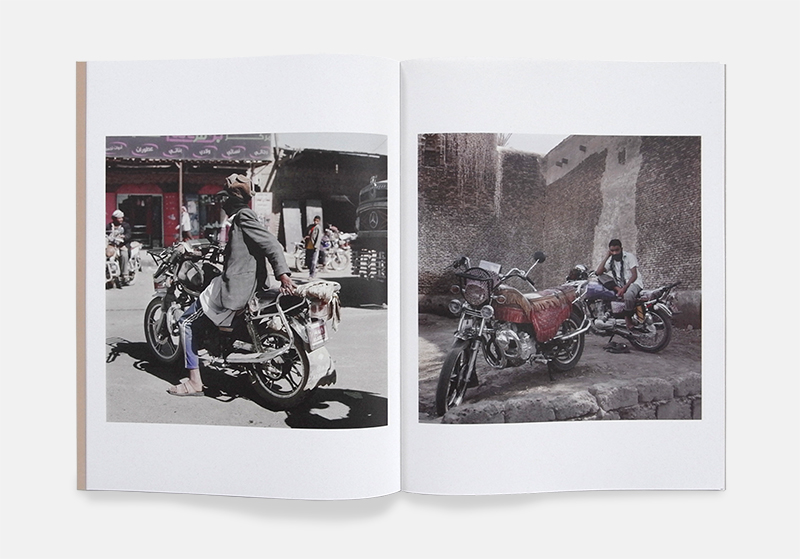

Nada Es Eterno by Guadalupe Ruiz, POV Female Bogotá

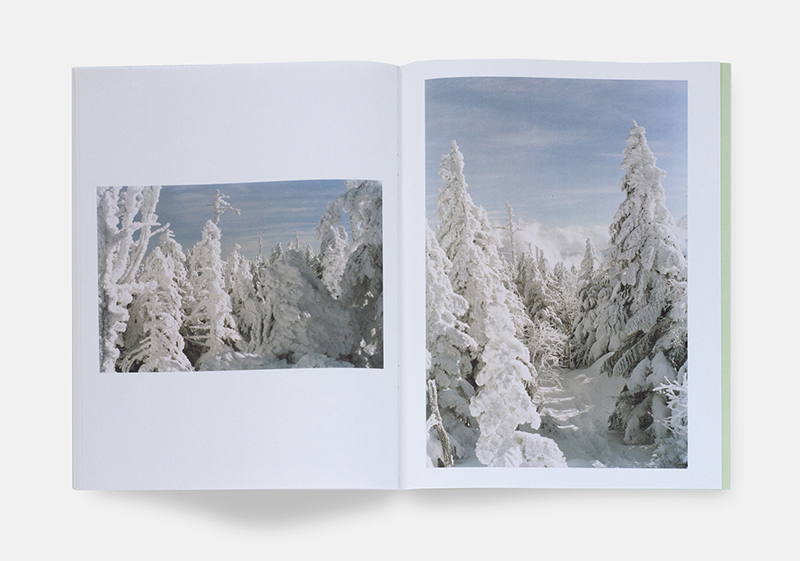

Winter Mountains by Kasane Nogawa, POV Female Tokyo

So how did you find the photographers you wanted to collaborate with? I imagine that in London it was quite easy, given that you’re immediately connected to groups of people doing lots of interesting work. But then with the other cities, how did you branch out and find the photographers that you wanted to work with?

At first I send an email to my contacts, then I use the social networks to spread information about the project. Further, I was lucky to always find a person who responded positively to the project and provide me with help in finding more photographers and connections to organise the launch of the project.

So there were quite a few connections between the photographers?

Not always. What is beautiful is that when we launch each project, we create the missing connection between the photographers in cities such as Johannesburg, Bogota, Beirut where the female photographic scene is totally unrevealed.

Are you planning on working with them again?

I’ve discovered amazing talented photographers by doing this project. Yes, I will work with some of them in a near future.

As we touched on a bit, the series has moved to look at places that have a very marginalised representation in photography. Do you plan on continuing it in that way?

Not necessarily, for this project it was relevant to work with marginalised cities as the subject of female photography is also marginal. I wanted to create a dialogue between all the layers of the project: the subject, the cities, those women…

So what’s next then?

Well, I’ve started working on a new project for next year. It’s too young to say anything about it. POV Female lasted five years, which is a long time. I guess good things need to end. But POV Female gave me a beautiful impulse to create other projects.

Real Prince by Ayla Hibri, POV Female Beirut

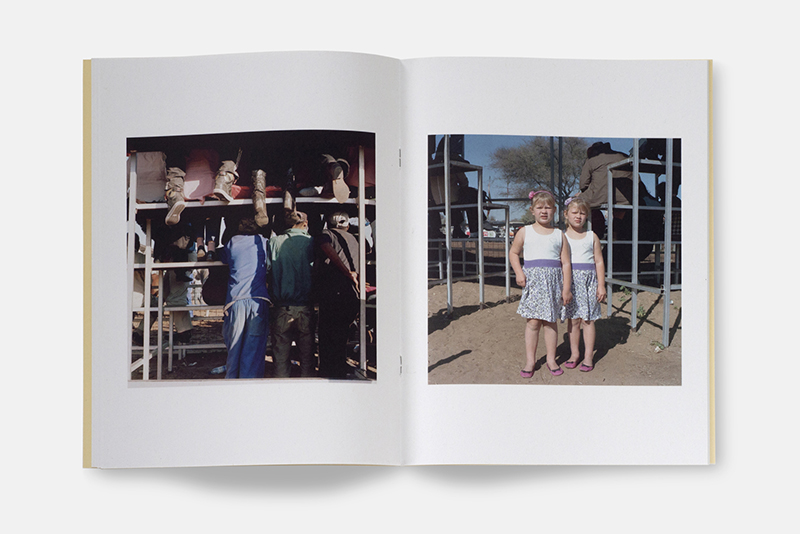

Ghanzi by Lisa King, POV Female Johannesburg

How did the working relationships with the photographers on the projects transpire? I imagine it’s the first book for a lot of them, and they will undoubtedly have their own vision for how it should exist, yet you’re giving them a template to work with. How do they react to that?

It was pretty easy actually. The format is always the same as l wanted to create a unity for the entire project. Photographers consider their work to be part of a collective project more than being a monograph. There’s guidelines, so within that I ask them to send me a certain amount of images. I work on a layout and from that point we start to argue.

So it’s much more a collaborative process then.

Yes, it is a collaborative process as with any publishing project I work on. I consider publishing as a collaboration, a dialogue between an artist and a publisher.

You make a point of having these books in quite small editions. Is that, in a way, you giving a certain value to the work by making a limited object and something that will at some point have a degree of scarcity and rarity to it?

It was important to create rarity as the photographers selected are discoveries; I see them like rare stones. Those past five years were times of intense exploration.

Now that the project is over, are you planning on finding a new way to present it?

POV female series is an anthology of emergent female photographers. Today, my desire is to show the entire project, to present the bodies of work of the five cities all together and create a debate on what remains and what it will become.

I think having a lasting legacy like that is really important.

More than a legacy, it is a testimony of female visions. It’s necessary to create testimony. In a sense, how you handle the testimony, makes the legacy.

Do you think in a way that it’s helped the careers of these photographers?

I think that for lots of them, it is the case. It really depends on the photographers and how they use the project to fulfil their career. In each city there’s always one or two photographers that gain more exposure. I cannot tell the full extent of what they will get from the project, but they definitely get some exposure and in a certain way, credibility. It is already a good base to build connections and maybe more.

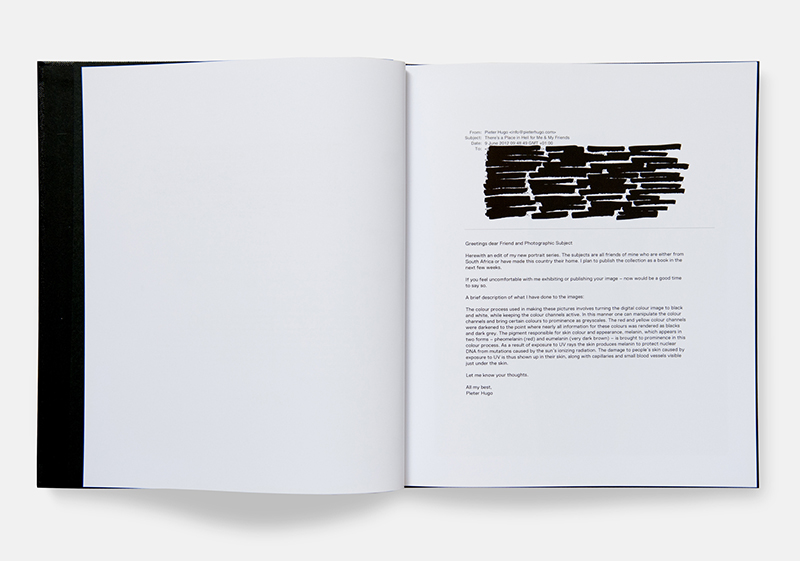

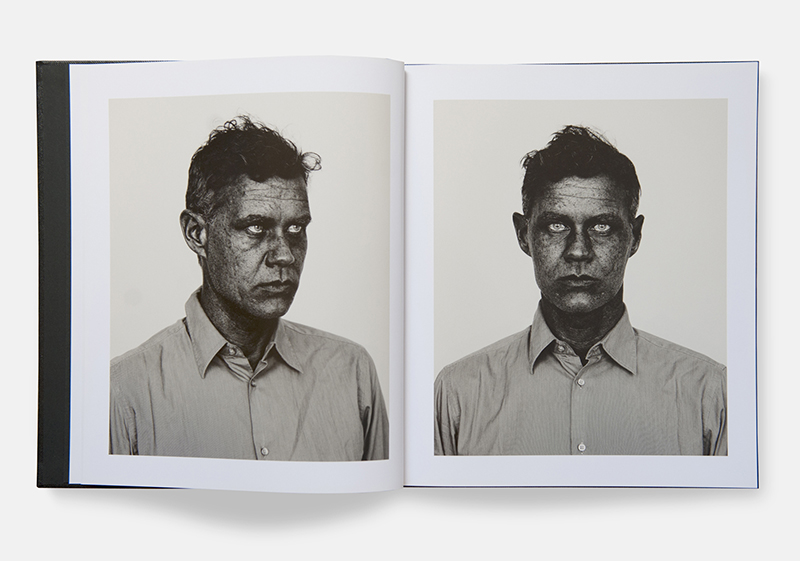

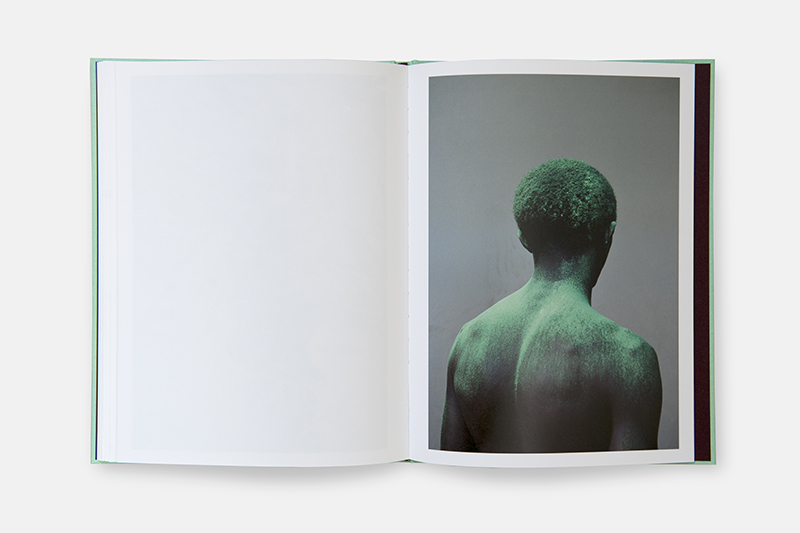

There’s a Place in Hell For Me & My Friends, Pieter Hugo

You’ve also done books with photographers that are quite established, and while the books aren’t large, in-your-face coffee table books, they carry a certain weight to them that is significantly different from the POV Female series. Are they two separate things in your mind, or do they bounce off one another?

Well, they do and they don’t. They are two exercises in publishing. In a sense, they complement each others as they establish a balance between the artists and create a diversity. However the expectations of an emergent artist and an establish one are not the same. Another element to consider is time; POV Female books are part of an anthology while the other books produced are monographs. Sadly I cannot devote the same amount of time for the artists part of the POV Female anthology, knowing that I work with five artists at the same time, and an artist working on their monograph. In consequences, it cannot have the same approach during the process.

I can see that. The books you’ve done with Viviane Sassen and Pieter Hugo are quite distinct from the books they’ve created with other publishers.

My experience with the photographers that I collaborate with reveals a natural and creative dialogue in time. When I worked with Pieter Hugo, Viviane Sassen or more recently Roger Ballen, we created a dialogue in order to think of the book as an important piece of their body of work. The book is not a tool to illustrate their work; furthermore it complements their vision. What I propose to each artist is to create a publication that can be unusual and more personal, more raw even.

You don’t produce that many books a year. There’s the POV series, and maybe then one or two more. Is that something you’re planning on expanding on, or are you happy operating at that level of output?

The POV Female series is an important work to produce every year. It didn’t allowed me to focus on more than two others monographs in the year due to the time it took to produce the series. Now that the POV Female project has ended, we’ll produce books with another rhythm. I also consider ‘publishing as a necessity’. There needs to be a reason to publish a body of work, there are so many artists who become obsessed by publishing a book which is driven by an impulse to shine. I think making a book isn’t always necessary. Perhaps a project needs an other element to fulfil its potential.

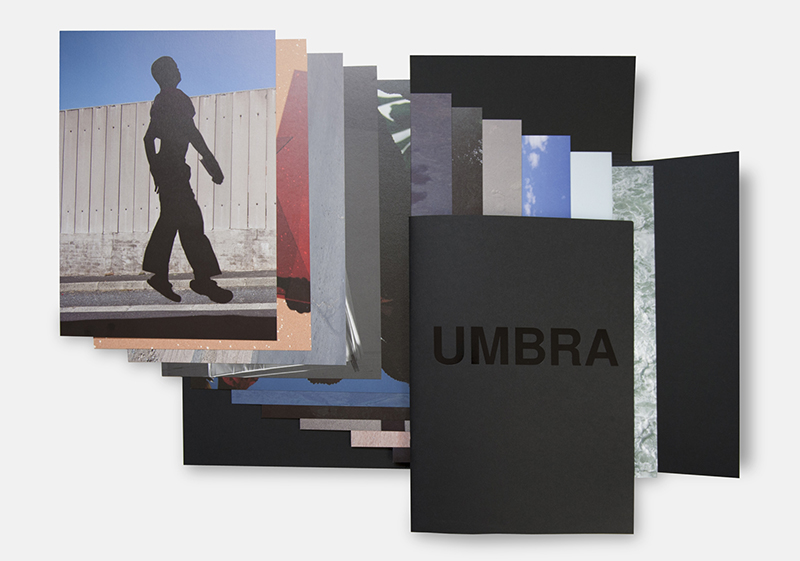

UMBRA, Viviane Sassen

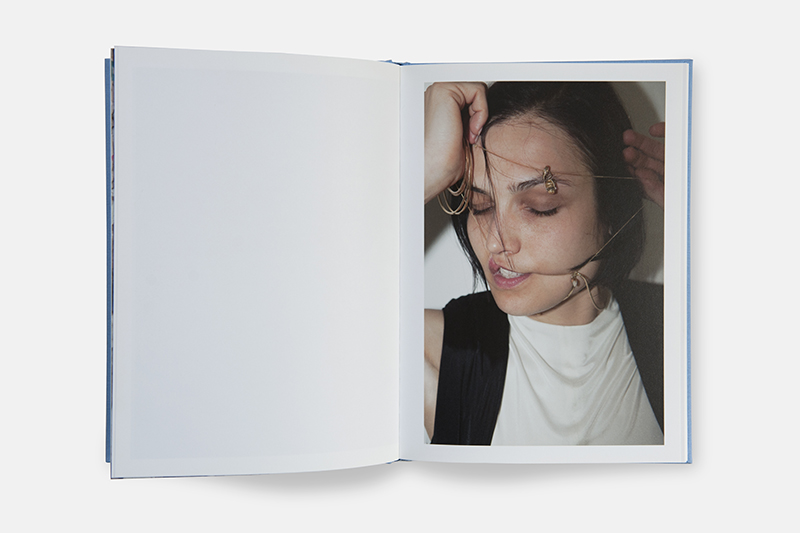

Roxane, Viviane Sassen

Etan & Me, Viviane Sassen

I think that’s reflected in the books you produce; they aren’t projects that work in every format and you seem happy to move away from what people would consider a traditional book — publication is probably a better word — and work with what the project is willing to give. As you say, you work to what is necessary.

I like elements which evolve and take different shapes. I like to be surprised and I appreciate when the object, the book, challenges the audience and creates different layers of reading by its subject, its shape, its materials, its design, in order to create harmony. Sometimes it can be easy to restrict ourselves to the possibilities of what a book can be and can lead to. I consider publishing a responsibility, so it becomes important to publish what is necessary.

Especially with photobooks now, though that term is very restrictive and doesn’t really speak about what the book is.

My main reference for books is the artist books. I have strongly been influenced by an exhibition that I saw in Paris in the 90s. It was on artist-books, it featured artists who were making books by themselves — artists such as Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha… those artists were using the medium of the book to express themselves and for me this is what I intend to do. I look at an artist’s work and I try to express their vision through the medium of the book. I don’t think of it as a photobook. Books can contain text, drawings, anything relevant to the content. The book is a platform for different ways of expression. But you’re right, it’s so restrictive to describe them as photobooks, because you expect to see only pictures and it conditions the mind.

Do you think photography publishing is in a bad place at the moment then?

We’re living in an interesting time, where we have access to incredible tools allowing us to produce more and faster. We’re not dependant anymore on big structures to express ourselves. The advent of social media gave an impulse to many to establish their own publishing houses and perhaps accomplish their dreams, as to the photographers to publish their body of work.

Paper was declared dead in the year 2000 when everything turned digital. However paper kept its great value and was considered for thoughtful projects, often in a smaller print run, which allowed many more independent publishers to be self sufficient and photographers to self publish their work. Creatively, it is really inspiring to be surrounded by so many artists and publishers however this phenomena reminds me of the 80s where the fanzine culture was going strong to then disappear completely, leaving place for compelling and commercial projects.