Rhonda Holberton – Still Life

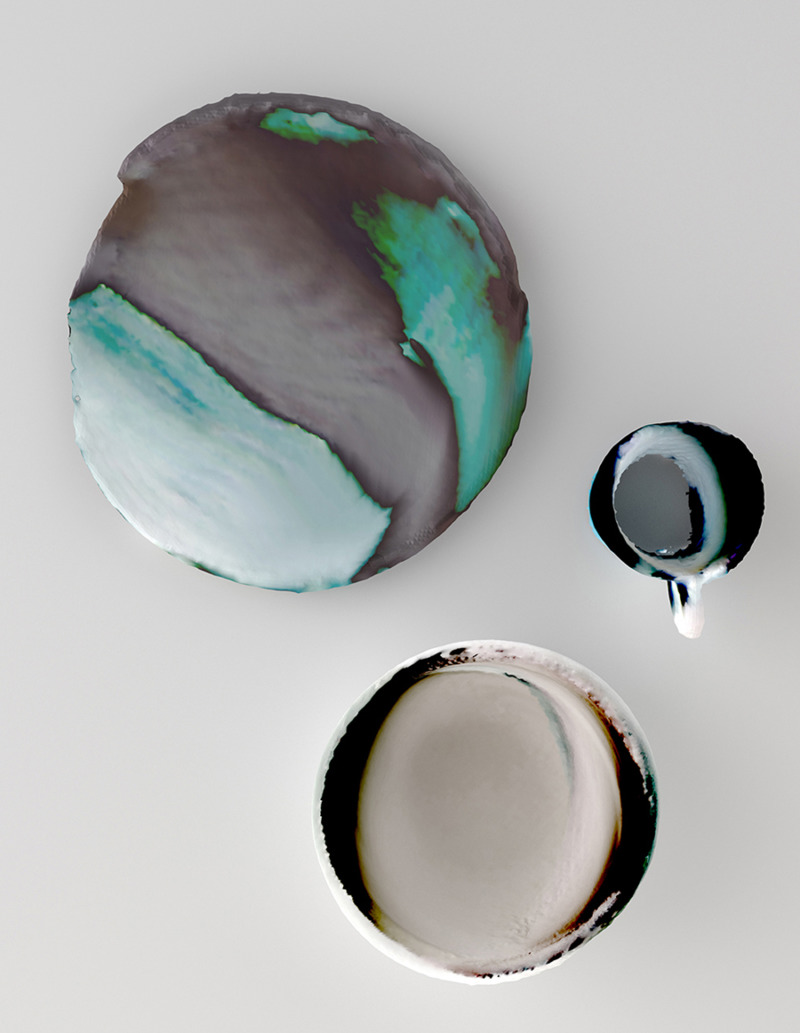

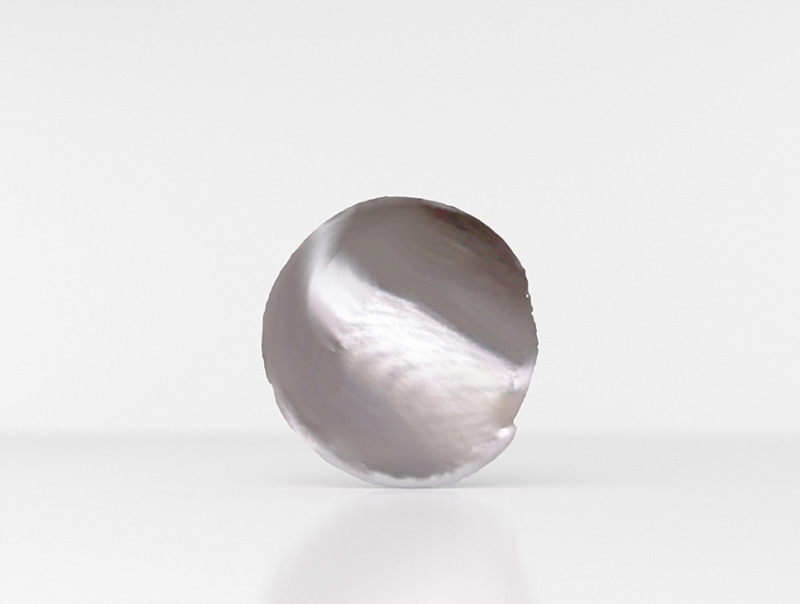

As Rhonda Holberton talks about her process–describing with her hands the arrangement and heft of the objects that appear in her images–it’s hard not to think of those things and that space as real. But everything, from the objects themselves to the flawlessly diffuse lighting and cool white marble ground, is digitally produced. Holberton makes 3D scans of real objects, then places them in virtual spaces of her own creation using Blender, an open source software suite. Her recent series, Still Life, braids together the real and virtual worlds so tightly that it becomes nearly impossible to separate one from the other.

In the twenty-first century, most people navigate between real and virtual worlds dozens, if not hundreds, of times daily. We project ourselves into GPS maps, have face-to-Facetime conversations, wear Snapchat filters like masks, or send avatars to explore virtual spaces online. We don’t often mistake the stuttering of a Skype call or the low-resolution of a picture on Instagram with failures of perception in the real world. But, Holberton’s presses on these limits in representation, challenging us to recognize digital noise, to make meaning from it, rather than filtering it out. The 3D scanning process is often imperfect, so while her creation of the surrounding space is utterly convincing, the image of the original object displays glitches. The artifacting in her images makes literal the raggedness of this movement between the real and the virtual; it is this haphazard, improvisatory character that tips her images into the uncanny. They are too close to real.

The question raised by Holberton’s work is not just look how much these pictures look like each other, but look how much the real world here looks like the real world there and there and there.

The genre of still life painting, to which the title of Holberton’s series alludes, has historically demonstrated a cunning awareness of the differences between things themselves and their images. The Roman xenia motif symbolized a host’s generosity through a display of painted foodstuffs, which could not be consumed. The depiction of opulence in the Dutch vanitas genre was a warning about excess, even as excess was made present through the pictures. William Harnett and John Frederick Peto’s popular nineteenth-century trompe l’oeil paintings were sought out precisely because viewers delighted in deconstructing their experiences of deception by picking apart the difference between the real world and its copies.

It is harder to identify the gap between still life in the contemporary vernacular and the things these images represent. The images that inspired Holberton–minimalist stagings of art books, succulents, and ceramics found in publications like Cereal and Kinfolk–seem merely to be beautiful photographs of covetable objects. Yet, unlike Harnett or Peto admirers, viewers of Holberton’s images on Instagram are often stumped by her “Still Life” pictures. Some commenters read the pixelation or artifacting as a unique ceramic glaze, even as bits of apparently three-dimensional objects crumble in front of their perfect white backgrounds. While recent criticism has focused on social media’s sleight of hand, where messy, unfiltered life is distilled into enviable images, what Holberton’s work brings most startlingly to light is the very constructedness of contemporary life itself. Baudrillard would agree that there are few surprises IRL; walking into boutique hotels, staged homes, and restaurants around the world seems more and more like Instagram come to life. They have become living images of themselves.

The question raised by Holberton’s work is not just look how much these pictures look like each other, but look how much the real world here looks like the real world there and there and there. Doesn’t that make my little shrine to potted succulents or kilim carpets as much a reproduction as any photograph? The more layers of mediation that Holberton inserts between the putative real object and her image of it, the less any of these distinctions seem relevant. Is this cute little hand-woven basket one that Holberton owns? Or is it a picture of one found online? And, most importantly, where can I buy it? Holberton’s dissembling images, that pixelated glaze that seems a cross between Heath ceramics and sci-fi horror, reveal the yawning emptiness that retail therapy struggles to fill.