David Brandon Geeting – Infinite Power

Infinite Power by David Brandon Geeting (Pau Wau, 2015), BUY

In the end we’ll be left with stuff, lots of stuff. Lampshades, neon pot holders, desk lamps, and Venetian blinds that no longer work. They fill our storage spaces, closets, get left on the curb, or sit on the shelf waiting to be bought. For artists, the refuse of modern life have long provided fodder for artistic investigation. By bringing the mundane items of everyday life into the studio or seeking them out in the world, artists direct their often critical, but transformative gaze on the objects before them. Drawing on a range of visual influences from amateur images found on Craigslist and eBay to stock photography, David Brandon Geeting makes images that defy easy categorisation. Combining still-life with more observational images captured outside the studio, Geeting omnivorously devours the odd and mundane in a fascinating and often nonsensical mix.

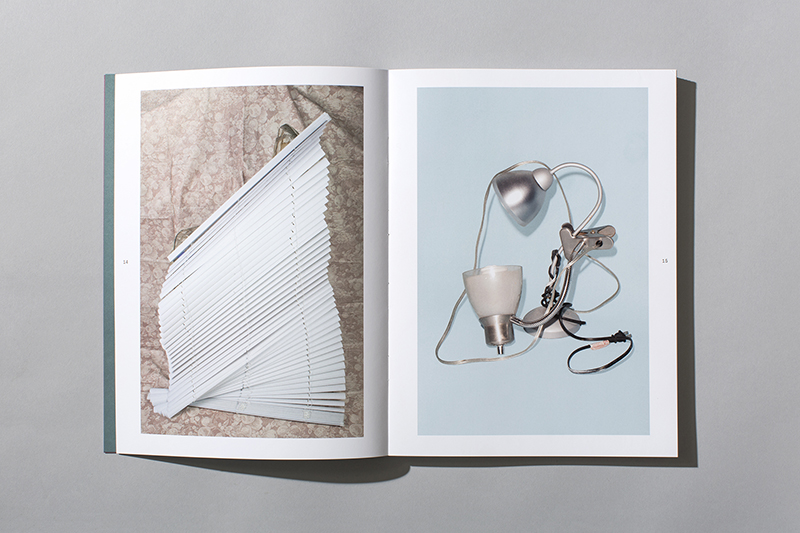

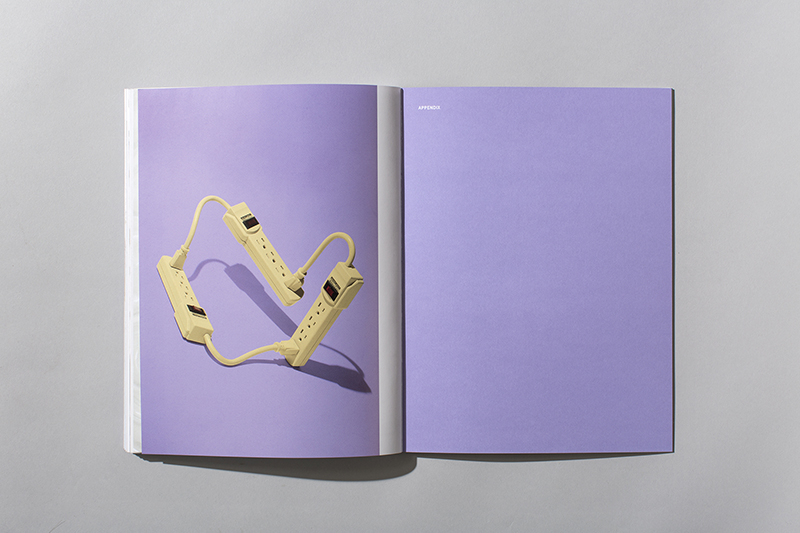

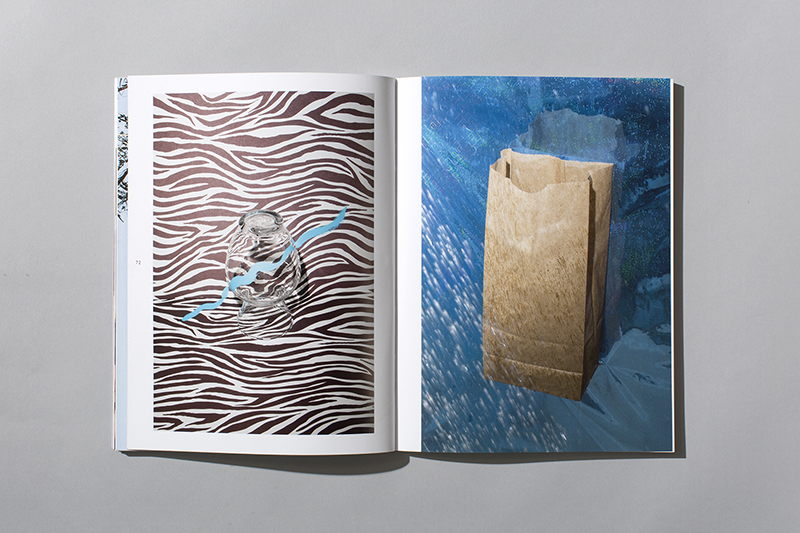

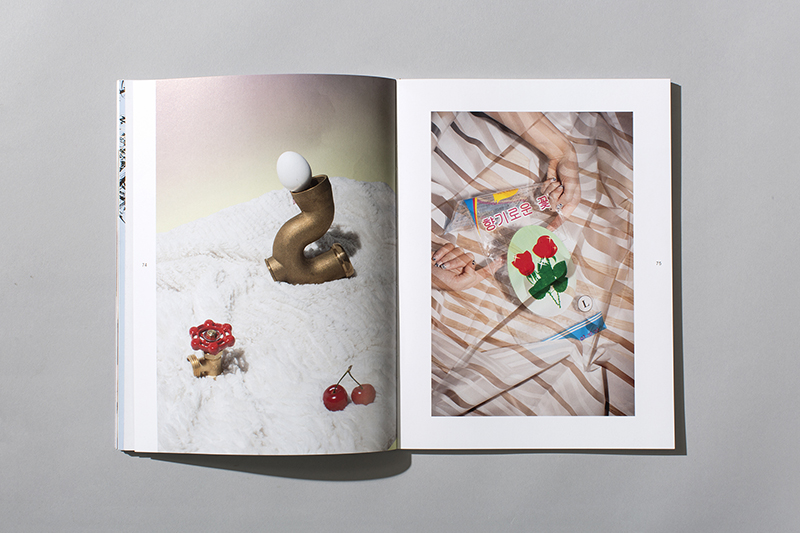

A commercial and fine-art photographer, Geeting is perhaps best know for his peculiar still-life photographs. Like much work created in this genre’s recent revival, Geeting combines prosaic objects that one might find in a 99¢ or hardware store in purposely jarring configurations. Brightly coloured and lit with a strong flash, Geeting’s images make use of a disorienting framing that temporarily abstracts the objects and space. Unconcerned with both the objects’ functional or symbolic meaning, Geeting’s probing camera and flash expose and strip his subjects bare. Blinds dangle in space, desk lamps float in pastel color fields, and marbles rest uncomfortable in a jagged pile of peanut butter. Each image feels like the result of a baffling challenge. Intentionally ugly and oddly composed, they flirt with failure.

While Infinite Power includes many such still-life, it also includes images shot out in the world that are as vexing as his still-life. Whether it is a pink pigeon, deformed scrubs or palm roots, or a door handle wrapped with plastic wrap and string, Geeting looks for absurd and optically confusing collisions in the real world. Included alongside the still-life, these images provide a slight counterpoint to the insular world Geeting creates in his studio, but they also extend that space into the outside world, revealing it to be equally strange.

Handsomely printed and enclosed in a plastic bag with the title printed on it, Infinite Power brings together a selection of Geeting’s photographic work over the past few years. As Geeting states, the “book is a complex collection of nothing.” Like this self-deprecating assertion, the book’s tongue-in-cheek title, which is actually named after the book’s final image that shows three interlocking power boards, makes sarcastically grand claims for the images it contains. But it also begs the question, what power? If the photographs in Infinite Power have any power, it is in their mercurial and elusive nature, which is indeed infinite, but not in ways that most hope.

The book opens with a foreword by the writer and poet Christopher Schreck, whose 2012 essay, On the Still-Life New Wave, should be read by those interested in the resurgence of the still-life genre in contemporary photography. Comparing Geeting’s images to Magic Eye illustrations from the 90s, Schreck argues Geeting’s images contain an underlying order that transcends their garish subject matter and casual appearance. As formalist exercises with little unifying meaning, it might be easy to dismiss the work as meaningless, but that misses the point. Although publicly disavowing influence and deeper meaning, Geeting’s formalist explorations have a long history in the medium stretching at least as far back as Edward Weston’s photograph of his toilet. As Schreck notes, Infinite Power is not only an exercise in visual pleasure, but also an exploration of how images shape and determine perception.

By now we’re used to the ways image circulate and float freely across multiple platforms. The convergence of digital technologies and social media platforms have accelerated not only the rate of image creation, but also the ways we view, disseminate, and share images. Blogged, reblogged, shared, and liked, images float freely or are orphaned and left alone to drift in the eddies of the internet—waiting to be resurrected, rediscovered, and appropriated again, their meaning perpetually in flux. As a product of this post-digital environment, Geeting’s images are beholden to no one, ready to be reblogged and shared, seemingly powerless, but ready to spread like wildfire.