The 34th Hyères Fashion, Photography and Accessories Festival

Nestled midway between holiday giants Marseilles and Nice, the lesser known hillside town of Hyères sits along the Côte D’Azur, abundant in its appeal with white sand beaches and the remnants of aristocracy. Though it doesn’t see the same flock of tourists as its neighbours, it most notably hosts the annual Hyères Fashion, Photography and Fashion Accessories Festival. Now in it’s 34th edition, this year the international festival takes place from the 25th to the 29th of April at the modernist house of Villa Noailles and showcases talent found across all areas of fashion and photography with creatives flying in from around the globe.

The 10 finalists in each category compete for prizes that are designed to promote and support emerging designers and photographers. The fashion Grand Prix prize offers a range of rewards but most impressively, a grant of 20,000 euros and the opportunity to work on a project with CHANEL’s Métiers d’art; the Chloé Prize and Prix Des Métiers d’Art also follow similarly in kind. The Grand Prix winner of photography is also awarded the same cash prize while the American Vintage Photography Prize and Still Life Prize winners take home a smaller (but still impressive) sum.

Year after year, the festival sees diverse fashion luminaries leading the way for young designers and photographers. In 2018, designer Haider Ackermann lead the fashion jury, which included Dazed Media editor Jefferson Hack and actress Tilda Swinton. This year, the festival continues to raise the bar with creative director of Chloé, Natacha Ramsay-Levi, at the head of the 14 member panel alongside fashion editor Camille Bidault Waddington and model-designer Liya Kebede. The 9 member photography panel also sees big names including Craig McDean who will lead the team, creative director of AnOther Marc Ascoliandmodel Guinevere Van Seenus.

For a festival that is regarded in high esteem, it continues to enjoy an enigmatic presence with little known about the participants and their work. In this feature, Paper Journal hopes to demystify the competition with a closer look into some of the fashion and photography finalists you ought to look out for in the future.

Andrew Nuding

You became a professional photographer at a very young age and shot for American Apparel at the age of 17. How did this come about?

When I started getting into photography I never really saw it as a future career for myself, I was just taking pictures of my friends. It wasn’t until American Apparel first approached me that I realised what I could do with photography. They wanted me to continue photographing my friends but using their clothes. At the time (and before Instagram) one of their creative directors had come across my ‘photoblog’ and that’s how the connection was made.

What’s the relationship between your initial work to your work now?

An aspect of my work that has remained the same throughout my years of photography is that I have always shot using analogue. I find it allows you to be more precise and give more thought to each photograph taken. I also think now it is harder for me to shoot something without there being a concept, thought or story behind it.

How do you think your studies in Fine Art Media at NCAD, in Dublin helped shape you as a photographer?

Studying fine art had a big impact on how I approach photography. I really liked how broad Fine Art was and loved being able to change between mediums. I could do one project on photography but also do another using video, sound, or sculpture.

Over the years, you’ve built an impressive portfolio, having shot for Dazed, Simone Rocha, AnOther Magazine and many more. How do you view the relationship between your fashion and personal work? Do they overlap?

Yes, I think it’s hard for them not to. Everything you do is slightly paralleled to your other work. The series for Hyeres is a jumble of fashion, portraiture, and still life.

Your 2016 work “Apparitions” features many religious symbols such as out of place church pews in a garden and religious figures on the dashboard of a car. Did your Irish heritage play any part in fueling this religious theme?

Growing up in Ireland, it was hard not to notice the hundreds of Virgin Mary grottos – pretty much every Irish town has one of some sort. The Catholic church used to have a lot of power in Ireland when I was growing up, abortion and gay marriage were still illegal. The series Apparations was my way of highlighting the surreal and bizarre stories, photographing places where the Virgin Mary had appeared. The stories of the apparitions are fascinating and it brought me all over Ireland. I focused on the Virgin Mary grottos that had the most interesting stories behind them and while shooting this I realised that these places that were once full of people had now become almost derelict. No one was going there anymore.

The body of work you’ll be showing at the Hyeres festival is brand new and hasn’t been revealed yet but could you give us a hint of what we’ll be seeing?

The series is called “Making Strange”, it is a still life and portrait project about the everyday. The title ‘Making Strange’ comes from the Irish phrase – to act nervous or shy when encountering a stranger or strange situation. I used this phrase to anchor my narrative, choosing objects for still life images I would encounter on my every day and then creating a portrait image to mirror this or vice versa.

It’s a project I have been working on for over a year that has been one of my favourites to shoot. I collaborated with an Irish stylist and designer, Kieran Kilgallon, who makes intricate clothes from charity shop bargain bins and also borrowing from amazing unknown student fashion designers. There is a great story behind every image. I also worked with my good friend Mary Clohisey who works as a set designer in London.

Hubert Crabières

Much of your work sees a connection between two characters or often we are given an intimate view of someone as they look straight into the camera. In this way, what kind of relationship do you build with your subjects?

The relationship to the subject is a central theme in my practice and I use staging to explore it. I ask the model to be himself in a completely artificial situation. In this sense, my images are not totally theatrical or cinematographic situations, nor are they stolen moments or documentary views. They oscillate between these different genres as fields of experimentation. I am therefore interested in what the tension between an exposed form of intimacy and the distance, even the coldness, that the staging implies provokes. It is ideas of images that determine a shooting session, more than the idea of photographing a particular person. This is a decisive point because the relationship to the model is always subordinated to the relationship to the idea, which is a more rational and conceptual dimension.

Repetition is a recurring theme in your work. What aspect of repetition fascinates you?

Repetition is an aspect of my work that has become more specific over time. It came from the dimension that links my images to the question of intimacy and by extension to the questions of the stolen moment, of what could not happen again. I was interested in how to give a mechanical (and therefore repetitive) aspect to a staging idea, without making exact copies. My images contrast the uncontrolled domestic space with that of the staging (often in the centre of the frame). As for this work of repetition, it contrasts the identity of the model to which I give a great deal of latitude, with the project of the image, which is a rational construction. In addition, I have been photographing for the past few years, mostly in Argenteuil, where I live and work. My models are relatives, friends, family members. This dimension of repetition, of the recognizable, began long before it became a working angle. The set and the subjects come back from images to images.

Are there any photographers that you admire?

Chauncey Hare is probably one of my favourite photographers. I admire his ethics as a photographer and his social commitment, the concern for the subject he deals with and the way he manages to solve the problems of political work and his personal expression as an individual and as an artist. There is no form of romanticism in his photographs and I find it very powerful.

Most of your images are centred around your daily life, in Argenteuil, but we’ve also seen some contrasting work from your visit to Japan and Shanghai. How do you think your work changes depending on where you go? Do you find a common factor?

The staging is undoubtedly the point that brings my images together. It is ultimately a very generic term that includes many different relationships to images. In any case, the work of building a photograph is the most mobile dimension of my practice, the one that travels with me. It begins with an obsession with a subject, an object, something discovered on the spot, etc. From this obsession comes a collection work that constitutes the visual aspect of image preparation. I like to surround myself, or even accumulate, with many objects that stimulate my desire to create an image. The duration of these two phases has a determining impact on the development of an idea. During a trip, the very limited time implies a form of urgency that ties all the steps in a rather thorough way. The collection is determined by what causes my excitement on the spot, what I can or cannot bring back to France. It is the same approach as my work in Argenteuil but in a very condensed and sometimes much less controlled way.

How do you see the series continuing?

I still have many image projects to realize, whether for a more commercial field like fashion or in a more strictly personal approach.

With your work being shown at the Hyères Festival at the end of the month, more people will be exposed to your work. What can they expect to see from you in the future?

I would like to continue to develop my series, find new forms of collaboration, pursue publishing projects, especially with the Franco-Korean publishing house that we created with two friends, ces éditions.

Christoph Rumpf

You started at Modeklasse University with no background in fashion, sewing or drawing and essentially threw yourself into the deep end! Can you describe the kind of struggles you had to overcome?

Well, first of all I had to learn how to sew a decent looking toile and learn to understand how to create volumes etc. After that I think I struggled most with being super super proper and I still work on that because you can always be better and more precise and I love to learn all techniques and finishes. But as hard it was for me to learn how to sew and understand patterns as easy it was for me to design a collection surprisingly.

Who and what do you look to as a source of constant inspiration?

I am always seeing things that inspire me all day. As Diane Vreeland said “The eye has to travel” and my eyes to that in every situation, place and time and I got kind of addicted to it to place things and feelings in my collections. Lately I am very inspired by photographs by Pierre et Giles to be more precise and I always find inspiration in different people and different cultures.

Last year, the Grand Jury prize went to a duo whose designs condemned harmful practices in the textile industry. Do you ever feel any pressure in having to address socio political issues in your work?

I think nowadays there is no way around thinking about how harmful your work is to the environment. I use a lot of used fabrics from flea-markets in my collection and try to buy from dead-stock fabric shops and if not at least try to find the least harmful option of a certain fabric. It can be tricky sometimes but it is possible, even though sometimes you cannot resist a certain fibre.

You mentioned in a previous interview that you like to create stories around your collections. What was the story behind this one for Hyeres?

This collection revolves around a story of a little boy who grew up in the jungle without humans and turned out to be a long lost prince. Upon his return to his people to take on his role as sovereign. It is about finding oneself and about the contradiction that clothes were meant to protect but are now used as a form of self expression and beauty. It is a story about different kind of beauties and about the transformation of one person in his youth.

For those who may not have seen your designs, can you describe your aesthetic in less than 10 words?

It is always about strength in different forms and definitely my view on beauty.

Going forward, what’s next for Christoph Rumpf?

I think this question is easier to answer after the festival but I want to do another collection as soon as possible because the concept is already in my head for months and I cannot wait to share this story.

Jean-Vincent Simonet

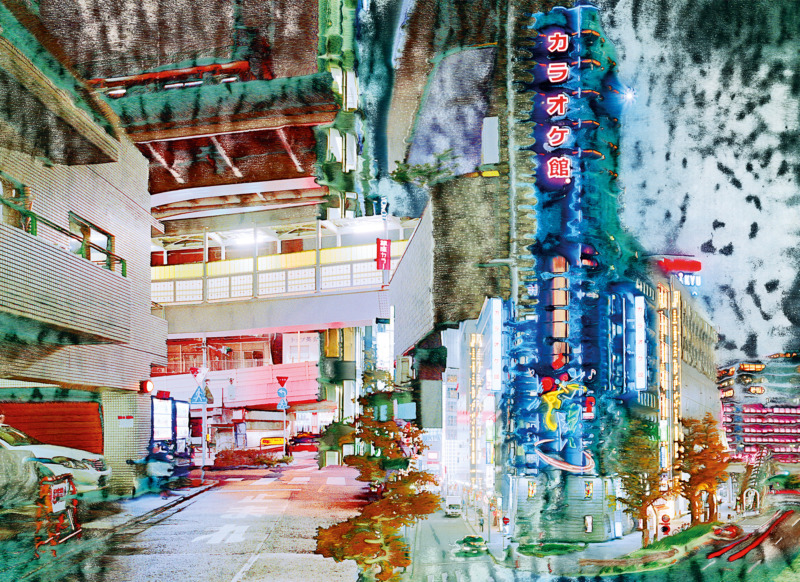

Your most recent series, In Bloom, was inspired by a trip to Tokyo and has a psychedelic, serene and chaotic quality to it. What was it about the city that left this impression on you?

In Bloom materialised after I first visited Japan in September 2016. With no particular project in mind, I quickly met two groups of young party people in Tokyo and Osaka, and began spending all of my time with them, taking pictures of our experiences together. Those nights were an intoxicating assault on my senses; various encounters, parties and late nights spent scaling the city began merging into one unfolding mass of visual information before my eyes. Part travelogue and part love letter to the cities of Tokyo and Osaka, In Bloom is a hyper-visual journey into the heart of Japanese underground culture.

When talking about your work, one has to talk about your technique. You’ve explained before that you print onto plastic paper and sculptural resin but you also use a whole host of non-traditional methods. Can you talk us through this process?

I try to get some primary material using every object that could produce a picture. There is no rules, it could be traditional analogue or digital cameras, but also iPhone, Infrared cameras, out-of-date films, pinhole camera, photograms, et cetera…

Producing this material is really the first step, most of the process and complications are coming when I try to find a proper way to materialise it through devious printing process including plastic foils, transparent paper, chemical, resins, heating of freezing.

Who and what prompted you to start experimenting with technique and mix digital and analogue photography?

My father is running a printing factory, so I guess I have always been in contact with those machines and sensitive to materiality. I also have a geeky side, reading those 300 pages instructions manual and playpen with chemistry.

Last December you held your first London show at Webber Gallery. As well as an exhibition, there was a ‘printing performance’. We’re intrigued as to what a printing performance looks like?

The idea of the printing performance was to show to the visitor of the exhibition a« live destruction » of small sized images from the book In Bloom. We prepared the day before few prints on plastic foil. After 24h drying and some special treatments, I washed it prints using water tanks and a syringe in the gallery, this is really graphic as some different layers of ink are slowly vanishing into the water.

Your ECAL graduation project was based on the book “Les Chants de Maldoror” and was quite dark and gothic, in contrast with your recent work which is very vibrant and full of life. How do you think you’ve changed since then?

I think there is not that much difference between Maldoror and In Bloom. Both are dealing with my direct surroundings. Both are trying to be transgressive and inspired by literature. Both are dealing with experimentation on the photographic medium.

Maldoror is certainly more connected with teenage feelings. In Bloom is about having an experience as a foreigner. I don’t feel I have really changed.

What is most likely to hit you with inspiration? For example, people, books, places…

A mix between video games from my teenage and romantic literature.

At the end of this month, you’ll be showing your “In Bloom” series at the Hyères Festival, which is really exciting! What can we expect to see from you afterwards?

I will show a new series called Izu Ravers, also dealing with Japan and experimental techniques on some really big prints just the day after the end of the festival : 30th of April, When the air becomes Electric, curated by Marco Poloni, CPG Geneva.

My next project will certainly be located in Kenya, but I am still at the beginning of it.

Kerry J Dean

Over at least 12 years, you’ve travelled to Mongolia for numerous projects, including Pom Pom Girls and I am Lost. Is there something about Mongolia that keeps drawing you back?

My first trip to Mongolia was to volunteer for a charity, working with Przewalkski horses; rare and endangered, they have been said to be the last wild horse remaining in the world. Honestly speaking, I went there on a personal journey that was not really about volunteering or horses. Mongolia felt to me to be perhaps the last wild place, and for once I wasn’t flooded with images and predetermined notions of what I might encounter before even stepping onto the flight.

That trip and the resulting body of work led to my first solo exhibition entitled, ‘The Emptiness of a Land with no Fences’. The images communicate the openness and sense of unending space that is so enthralling in Mongolia but in some ways, they seem quite naïve to me now. That said I still have them on my wall and I probably always will because they represent the start of an enduring obsession with the country and the culture.

Since that first series, I’ve stepped closer in, formed friendships, and become more embedded in the place. My images and my interests have evolved. I understand why people are beguiled by the yurts, eagle festivals and wrestling matches but they don’t draw my eye in the same way anymore; perhaps they just feel too sentimental to me and I now see a more nuanced version of Mongolian life.

The latest series, Observations and Orchestrations, looks at the odd beauty created by the clashes between traditional ways of life and contemporary culture. It’s these unexpected and incongruous elements of Mongolia that are the most intriguing to me now; a troop of small girls making their way to school, every one of them adorned with brightly coloured pom-poms in their hair; a trace of the communist education system.

The practicalities of the every day seems so theatrical, but I fear that Mongolia is a country in a unique period of flux. The profound differences I’ve noticed from when I first visited twelve years ago, confirm to me that there has definitely been a shift; the most intriguing and unusual aspects of Mongolian life, many of which I have been lucky enough to observe and participate in, will disappear under the tide of urbanization and digitization. In many ways, I am interested in capturing this transition but doing so while the clashes of culture it creates are still so apparent.

Time and place play a big part in your photography but often, the subjects in your images are just as captivating. What relation exists between people and places in your work?

Fundamentally my interests lie in the connection between human beings and their surroundings. With the more fashion-led imagery, I’m often working with the narrative of trying to understand how that person belongs or doesn’t belong to the environment around them. I’m less interested in the connection between them and me, which may sound odd given a lot of my work is Portrait based.

In recent days, what inspires you to create?

Motherhood. The shift into motherhood gives a new perspective on everything, including creativity. Time has a huge part to play and the perspective on it, having less of it, but equally wanting to spend it in a very different way.

I did a series of stills for Hyeres, entitled ‘Breast Feeding Obsessions’. Which were based on the time I had spent breastfeeding my son, pinned in one place, unable to move for long periods of time. Obsessing about the world of children, and all the new objects that had entered our house, in essence having a child allows you to see the world again for the first time.

You worked with i-D magazine on i-Sustain, a project that explored the link between fashion and sustainability, and for this assignment, you stayed on British soil. How did this compare to your exploration through Mongolian landscapes?

The i-D project was a real exercise in exploring my homelands. I’ve always been interested in travelling further a field, personally and professionally, finding excitement in the far away & the new. This project was a brilliant opportunity to explore and be inspired close to home, to look for the beauty on my own doorstep, which is particularly important when thinking about sustainability.

In addition to being an accomplished photographer, you are also a filmmaker. Is there something about this medium that helps you achieve a goal that say, you can’t do with photography?

I’m pretty new to the field of moving image. I directed a short film for artisanal brand Maiyet, documenting the ‘Fair’ cashmere project, which supports the livelihoods of nomadic herding communities in the remote regions of the Gobi Desert. I loved the auditory side of filmmaking, both whilst directing and also in post. The process of interviewing people, observing and recording the sound of a landscape and editing footage to sound is such a different experience.

In the run-up to Hyères festival, what’s an aspect of your work that you’d like people to know?

Ultimately I want people to feel something when they look at my work, I don’t really mind what, as long as it moves them in some way. Sometimes knowing something stands in the way of feeling so I’ll leave my answer there.

Róisín Pierce, Women In Bloom, Photography by Nicholas Quinn. Hair by Angela Doyle, Model Elen Dullaghan and Mia Sweeney from NotAnother, and Tara McGonangle from 1st Option.

Róisín Pierce

Congratulations on being a finalist at the 34th Hyeres Fashion Festival! Could you tell us a bit about the inspiration behind your collection for the festival?

Thank you very much! Mná i Bhláth (Women in Bloom) is a personal collection to me which pays tribute to the women who were sent to the Irish mother and baby homes such as the Catholic Magdalene Laundries (mid-1700s – mid -1990s). Women were commonly silently and secretly sent away for having children born out of wedlock. It is not widely known, but many women in these homes were forced to make handcrafted textiles, in particular, Irish lace and smocking as well as pattern-cutting for religious garments. The idea of labour and toil made the girls atone for their past ‘mistakes’ to amend and cleans themselves. The makers were anonymous, yet very beautiful things were made, allowing the Catholic Church to sell for profit. It is these techniques that are centrally important, but equally, they have been reinvigorated with new contemporary application and uses.

Flower forms and motifs are used heavily throughout the collection. Through my research, I discovered many flowers and flowering euphemisms and symbolism for women and sex, ‘blooming’ and becoming ‘ripe’ having ‘buds’, has long been associated with girls developing into women. Yet terms like ‘deflowering’ has been used to describe women losing their virginity for many centuries. Female sexuality has always needed euphemisms to cover up what had been perceived as dirty and shameful. (Especially in Ireland during these times, the Laundries highlight or prove this).

How would you describe your ethos is less than 10 words?

A constant desire to create something new.

In your “Man Repellent” collection, you subvert the male gaze and create shapes that emphasise “negative” aspects of women’s bodies. What drew you to challenge this view on women and womenswear?

I’ve long been interested in the psychology behind women’s choice of dressing, the reasons behind the clothes they wear, the question of whether or not women dress for themselves or someone else. I began to look at the idea of women dressing for male attention. I liked the idea of creating clothing that ultimately was the opposite of attracting others and that discouraged unwanted attention.

So creating sculptures that were resembled fat rolls, sagging breasts and hunchbacks (physical attributes that classically are seen as negative aspects in women bodies by Western society) that almost completely envelop the wearer was a fun starting point that fuelled a lot of pieces.

How do you see yourself pushing new boundaries in your exploration of textiles and construction?

Well in the past my collections the clothes were visually an examination of sculpture within clothing; almost as if the model was wearing one large sculpture.

This collection, Mná i Bhláth is more about sculpture worked within the fabric; a contemporary version of classic handcrafted techniques that visually become almost like floral sculptures; something I haven’t seen before. With each piece came the exciting challenge to show development, something I always aim to do.

I wanted the pieces to show progression in terms of manipulation, techniques, construction and variation. Almost like the collection was a visual representation of my thought process and design development with every garment. Constantly challenging myself to figure out new ways to reinvent garment construction. Such as; multiples of the soft sculptures are woven, linked, jigsawed, tied and appliqued together as well. For example in one particular garment multiples of soft sculpture were built on top of each other and slotted together. From this experimental textile application, I created a new way of creating a textile design. So I’m always trying new possibilities and playing with the material after I had developed my initial inspiration.

Many of your collections such as “Mná i bhláth” use a lot of white and beige colours with the exception of SS19 which incorporates a deep burgundy colour. Is there a reason behind the dominant white colour palette?

Well in this particular collection working with all white was a must, it references the only colour used in babies baptism dresses, Holy Communion and bridal dresses. (The garments the women in the Irish Magdelene Launderies were forced to create). I like to work in white also as it draws viewers to concentrate on the form and surface construction.

You’ve previously expressed an interest in agender clothing – is that something we can expect to see next?

Agender clothing is something that I think will always be of interest to me. I don’t like the idea of creating clothing for one type of person. So, absolutely agender clothing could be on the cards for the future.

Alice Mann

We noticed on your Instagram page that you’re currently in Cape Town. Is there a new project in the works?

I grew up here, and although I’ve been based in London for the last few years I am able to spend a lot of time in South Africa, which is where my work is focused at the moment. Most of my projects tend to overlap and I end up working with the same people on different things over long periods of time, so I usually have a couple of different things on at the same time!

Many of your projects like Maximum Effect explore marginalised and disadvantaged groups. Has it always been your aim as a photographer to document those ‘left out’ in society?

For me, it’s more about working with communities. The first project I worked on was autobiographical and was focused on my own community, and the space I grew up in. I try to examine how people within communities express and empower themselves through identifying as part of a collective. I think that what’s interesting in focusing on the way people reinforce their identity as individuals, is that often there are very universal aspects to this. I hope to make images that allow viewers to connect and identify in some way, rather than highlighting what is different.

Your hometown, Cape Town, has influenced many of your projects but out of curiosity, what part has living in London played in your work?

I think it’s also been interesting for me seeing how a lot of people perceive South Africa, which is very different from my own experience growing up there. I’m very interested in stereotypes in images, and the way they can reinforce or challenge our worldview. So I think having the chance to be in another space, and see how other people view the space I came from has been interesting. I’m also acutely aware of the inherent privilege in this, in having the opportunity to be based somewhere else, and the perspective that comes with this distance. This has been really helpful when attempting to make work about the complex, and very nuanced society that I grew up in.

Has there been a key inspirational figure in your life that got you into photography?

Not one, but a number of people, and experiences. I actually got into photography by accident, it was never something I planned on doing as a career! At university, I studied fine art and was persuaded to major in photography rather than painting because my marks were slightly higher (Although there were only 4 people signed up for the major at that point, so I think the lecturer wanted to get the numbers up!). Looking back I think there were a number of factors that came together in just the right way.

In your images, the subjects and their narratives are intrinsically related; and you’ve commented before that your projects take a long time. How have you connected with people in order to bring out these narratives?

For me, working on projects over a long period of time is a really important aspect of my approach as it allows me to form relationships with the people I work with. I try to facilitate a space where people feel comfortable, and where they feel confident to project what they want to the camera. The best way to do this is to step back and respond to people on an individual basis. Continuing on a series long-term allows narratives to develop organically and for me, this is always more interesting than a preconceived narrative that I might have.

Your Drummies series has been widely successful and earned you the 2018 Taylor Wessing Prize last year and you’re also a finalist in the upcoming Hyères festival. As your exposure widens, what do you want people to take away from your work?

It’s definitely afforded me opportunities I wouldn’t have thought of before, which is really exciting. I also feel that there is added responsibility with this, and I think it’s made me think much harder about every aspect of my practice. It’s really important to me that I can continue to express deep consideration and sustained engagement in my work.