Art Fair Round-up 2021 – 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

Since its formation in 2013, 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair has been at the forefront of promoting the African art market to international audiences and being a leading voice in the global conversation on contemporary African art through their exhibits in London, Marrakesh, and New York, every year.

This year’s fair at Somerset House featured the artworks from 48 international galleries, that represented a collection of contemporary artists from Africa and across the diaspora. It brought together a diverse range of carefully selected art projects from 23 countries across Africa, Europe, and North America which include: Ghana, Brazil, Nigeria, France, South Africa, Belgium, Morocco, Germany, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Italy, the Netherlands, Egypt, Uganda, the United States, Angola, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

More than 150 emerging and established artists showcased their work in a variety of media including photography, film, sculpture, embroidery, weaving, installation and performance. The fair was followed by the 1-54 Forum titled Continental Drift, which explored the “concept of the drift as a moment of gradual reflection”, delving into themes regarding legacy, digitality and philanthropy. It featured an extensive programme, curated by Dr. Omar Kholeif, Director of Collections and Senior Curator at Sharjah Art Foundation, of film screenings, performances, panel discussions, artists talks and readings that took place at Somerset house and online.

Founding Director of 1-54, Touria El Glaoui noted that due to the COVID-19 pandemic it has been a challenging 18 months, but that 1-54 was pleased through their partnership with Christie’s Auctions to have opened their first pop-up fair in Paris, in addition to running ‘a more intimate edition of the London fair’. El Glaoui added that 1-54 will continue to use the Paris space, and emphasised the importance of expanding in Africa, “We have such an impact there that is much stronger.”

Among the 48 exhibitors, Paper Journal caught up with talented photographers David Uzochukwu from Galerie no. 8, Nana Yaw Oduro from Afikaris, and Prince Gyasi from Nil Gallery to find out more about their work at the 1-54 fair and their wider art practice.

David Uzochukwu

Could you give me an overview of the photographs you exhibited at this year’s 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair? And what was the process like in photographing your subjects?

I showed four images from Mare Monstrum / Drown In my Magic.

Buoyant, of a mermaid drifting in the morning light, and Shrine, an underwater image of a mermaid with sea dragon tail, both shot in Senegal in 2019.

I’m always thankful for people’s trust in the process– with so much coming together in post-production, the immersive quality of shooting on location is actually quite a blessing. Both models were with Amy Management in Dakar at the time. Alima braved early morning swamp water in a metal dress, while Mame balanced on a stool at the beach pretending to float. We had fun.

Then there’s Styx, of bodies crowded together on a rock in the water, and Spectre, of a finned being glowing in the dark, both shot in Berlin later on.

I usually photograph a single person, maybe two, but for Styx, I wanted a crowd. It was interesting to place half a dozen bodies, to let people move and interact on that scale. It felt like staging a performance. And photographing Nayme for Spectre felt slightly like an extended self-portrait– working with complete strangers can feel really intimate.

Your work has an air of the mythical with an otherworldly, poetic presence, beautifully expressed. I’m interested to know what your inspirations and research interests are. Do you refer back to stories of Nigerian deities and mythological representations like Mami Wata? I also read that you’re studying philosophy at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Has it contributed to your artistic practice?

Thank you. I was inspired by a ton of fantasy and fairytales I gobbled up as a kid and teen. I was interested in Greek mythology, and then Mami Wata, and developed a greater fascination for more local water spirits. I would say that for the series, the hybridity of water beings became more relevant to me than the specificity of cultural figures though. Connecting their supposed monstrosity to Blackness felt right, the historic and political link between race and water fed into that – and then it was obviously satisfying to explore it from a creative point of view. What shapes would a merperson take on in warmer waters, in European darkness, can we show tenderness between merfolk, how do I push the sculptural quality of this tail?

I wanted to get continuous input and academia helps with that. The more I consume, the more links I can draw to my work, and then that circles back to my studies. Recently took a course on the concept of the hero and why it should be dethroned. That was extremely relevant to storytelling practices. Excited to let the practices extend into each other more.

I’m a Nigerian born in Vienna, Austria and was excited to learn that you’re an Austrian-Nigerian. What was it like growing up in Austria and living in Luxembourg, Brussels and now Berlin? As your work deals with identity and belonging, did your experiences between two cultures influence the work you do?

We’re everywhere! I have very fond feelings towards Austria, which makes the political situation there all the more painful. Luxembourg was essential to my development as a photographer with lots of physical space to roam. I could just leave the house and stand in a field ten minutes later. Brussels put me in touch with some exciting faces and cultural opportunities. Sometime after graduating from high school I took a yearlong stint to Vienna to finally be a foreigner at home again.

There’s definitely something uprooted about my upbringing that flows into my work. Outside of that, I feel like being racialized might have shaped it more than the specific cultures in our household.

When creating new work, what do you hope to achieve with the finished project? And how do you want your audience to perceive the work? Is it open to interpretation?

To me, that’s the magic of photography. I can pour something personal in, feel seen and yet protected by the ambiguous gap the medium leaves, and others hopefully react. There is nothing more exciting and flattering than hearing that people are able to take something from the work, and I regularly learn something new from their perspectives on it.

Are you working on anything at the moment and if so, what is it about?

I’m finalising a film installation that I’ve been working on during the pandemic – looking forward to sharing that soon.

Where can we view your next exhibit?

The Prix Pictet group show opens at the V&A in London on December 16th. In the meantime, I’m showing some Mare Monstrum / Drown In my Magic photographs at Melkweg Expo, Amsterdam until December 5th. See you around, I hope.

David Uzochukwu is represented by Galerie Number 8.

Nana Yaw Oduro

As a big fan of photography and the way it portrays our thoughts, emotions and how it captures what’s going on in our world, I loved the series of images you exhibited at 1-54. What were your inspirations behind the images?

The series that was on view at 1-54 London is called If we play like this, we stand a chance. It has been inspired by the period of confinement we all experienced last year. Being locked without knowing if we would be able to go out again one day made me think that enjoying any moment is more important than ever. So, we won’t have any regrets about having missed the occasions to do what we like and to enjoy life. This is what this series embodies: If we enjoy any seconds of our life, we would not have any regrets. Thus, these photographs are a way to remind us to live every day as it would be the last. It is also a statement that we won’t let the lockdown bury us.

The photos you create have a cinematic essence to them. Like stills we could see in films by Barry Jenkins such as Moonlight. Talk us through the process when embarking on a new project?

My new projects pop up in my mind when I don’t expect them. They can be triggered by a conversation, a specific moment, a song I’m listening to or something I see in the street. I choose my models to play the stories I imagined in my head. Spontaneity also plays a main role in my projects. Sometimes, I decide to add central elements at the last moment. It changes everything visually but participates in creating what I feel I want to show through my pictures.

Your work emanates joy. How do you use colour in illuminating the story you’re telling?

My photographs translate my emotions. The pictures I produce remain subtle and don’t show strong contrasts in colours. They are punctuated with touches of colours to attract the attention of the viewers. For me, colour is a way to anchor the image in a specific universe. It is also a signature.

You come from a business background having studied marketing at the University of Ghana. How did you get into photography and the creative world? Was it something that’s always interested you?

I started taking photos with my iPhone to express and share the stories emerging in my head. Posting them on social networks allowed me to find my public as well as a gallery to represent my work. If I studied marketing, I always knew I wanted to do something different.

Described as fictional self-portraits, your work which explores boyhood, masculinity, self-awareness and acceptance, has a poetic composition. What do you look for when creating the visuals?

When I’m shooting a new series, I first aim to translate my emotions through the images I compose. My feelings guide my work. Photography is for me a way to express myself and to give life to my thoughts.

What’s been your favourite work to date and why?

I think my two favourite works are Trojan Horse and Fruits are for Boys. These two series made me a photographer and not only someone taking photos for fun. A lot of people all around the world enjoyed these series and could identify themselves. So I think it’s the most beautiful reward as a photographer.

Nana Yaw Oduro is represented by Afikaris.

Prince Gyasi

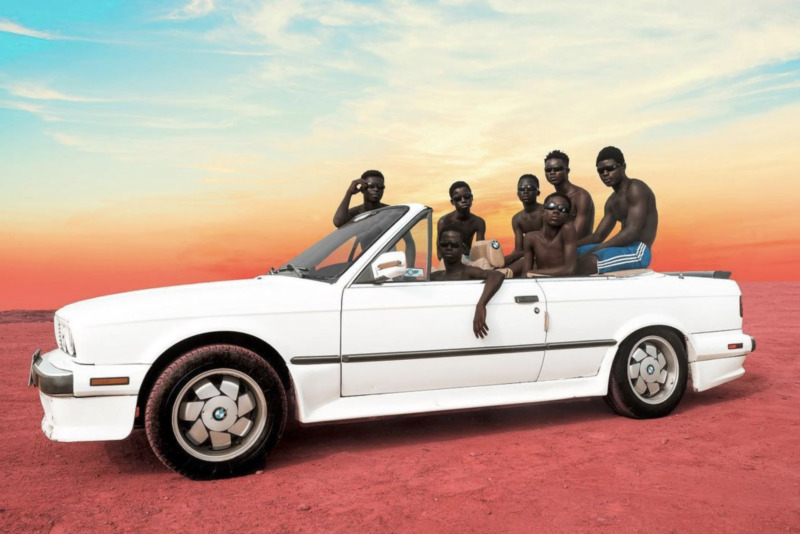

I was immediately captivated when viewing your wonderful photographs at 1-54. Could you talk us through creating the series of images you exhibited at the show?

I shot the series in Ghana. It’s a continuation of the same topic that I talk about every time, which is child education in Jamestown because my mom went through the same experience where she couldn’t further her education. She didn’t have the means to pay for tuition. What I’m doing now is I’ve put twelve kids in school. I’ve got one kid who is going to high school next year. And basically taking percentages of whatever I make from my art pieces and personal work which I invest into the kids and make sure they have the best education they can have. The series highlights the problems we have in society as Africans and also making sure that these kids understand who they are and their identity.

I’m lucky to be here because if my mom didn’t sacrifice so many things for me to be in school, I would have been like one of those kids on the streets. So I don’t take anything for granted. I’m not one of those artists who’s using the kids to create art. I went through the same experiences. I came from a very poor family.

My mom was lucky enough with her music. She blew up as a gospel artist and a fashion designer, so she had some money. I don’t think I would be here right now if she didn’t make all those sacrifices. So many sleepless nights. There were times she was sick and chose to go to work because of us. I’m not taking it lightly.

This whole series is about empowerment to the young ones in Ghana and other countries, because I’ve been to other African countries that still have the same problems. Even my people is Salvador, Bahia or São Paulo. We all have these issues. I have quite a number of people that follow me on socials who DM me every time and I see the emails, and they have the same problems that we face.

I thought your images were paintings until closer inspection made me realise they were actually photographs. The striking contrast between the beautiful brown hues of your subjects against the colourfully, bold backgrounds, leaves for memorable viewing. Are there stories you’re trying to tell with each image?

Yeah. Some of the pieces that you saw like Treasure Trove are telling people that they don’t need to go underground, or to the deeper part of the city to find out who they are. All they have to do is take things seriously and invest, then help change a kid’s life, you know, and stop judging and discriminating against them. In Ghana, there’s a big problem when it comes to classicism. I mean, yes, it’s a global issue, but in Ghana, it is very intense.

In Africa, they would rather respect a white person than a black person, giving the best things to the white man, and not to the black man. This issue is something that people have been going through for so long.

Do you think it’s the shadow of the colonial past?

It could be but it’s also about money and people. I can classify that under fantasies and people not having access to certain places. It also has to do with education. Everything that we talk about, every issue comes down to education. Educating people about what is going on around them in society and what they are consuming. So most of these pieces I create are more like albums.

The pieces are all coming with the same message. But also, if you check all the series, you find a consistent trait of message all around them. It’s me not losing where I came from but also creating sub-elements from those stories. So you don’t have the same type of stories, but you’re going to have the same message, with different types of elements and different issues that I’m going to identify.

What I do is to create the problem and try to show you the solution to the problem. There’s a piece called Airborn (2021). You can see a helicopter and kids wearing wings going to drop gallons in the helicopter. They aren’t walking on a red carpet. They’re walking on a piece from Serge Attukwei Clottey. He created those pieces from the gallons, and it’s basically about kids who are trapped in that situation. Which is how their parents would rather have them work for them than go to school. So they indulge in fishing. I thought about what element I can use that will represent the whole bondage system that they’re in, which is water and was like, let me use plastic. Let me get Serge to create the map out of Jamestown on a plastic gallon to tell the story of kids actually leaving their baggage in their fantasies. Equipping them and letting them know that they can create their own luxury. They don’t need to grow up to get money to buy a Lamborghini. They don’t need to be thinking like that, they have to think about solving problems.

Airborn is letting the kids know that they’ve got wings within them. They don’t need to travel outside of the country to do what they have to do. I started with what I had, you know, I didn’t have to meet Jay Z or Kanye West to be able to do what I’m doing and I just want the kids to start thinking that way, to prevent them from committing criminal acts because they never had that type of education when they were growing up.

One thing I want to add is that the piece is called Airborn, without an ‘e’. Growing up, I knew friends whose parents used to tell them don’t go to Jamestown because those kids are messed up in their heads. It’s telling these kids that you don’t have the same resources, these rich kids have but if I give you that resource, you’ll be better than them because you’re smart already.

I can see what they’re doing in the community. They’re creating cars out of milk cans and stuff like that. That’s creativity, that’s construction, that’s architecture, that’s engineering. I want them to understand that they’re already fly. They’re not a disease, ‘airborne’ with the ‘e’ is the disease. The outcast name that these people throw at them. So that’s why I used the wings to represent that they’re fly.

You’re known for using an iPhone in your earlier work instead of the camera in photographing your subjects. Did you get a lot of pushback when exhibiting your work back then or were people interested to see visuals that weren’t created by the traditional camera?

I’ve had this attitude of not actually thinking about what people are saying. I’ve always been in my lane, from primary school to high school to college to whenever. I didn’t care about what people said. All I wanted to do was to equip the kids. For them to know that it’s about the mind, not the tool and you can create whatever art you want with whatever tool or resource that you have with you at the moment. It’s for them to understand that progress is a marathon, not a sprint.

The iPhone photography was just to equip people. It’s not like I couldn’t afford a camera or anything. It was a campaign that I was doing to help these kids and people. And also it’s something that I loved to do. I loved the feeling of creating with an iPhone and people thinking it was shot with a camera.

I didn’t really have any pushback. It was more I think… some people thought I wasn’t serious. But at the end of the day, when they check the message, and they check what I’m actually standing for, they eventually accept it. I wasn’t looking for everybody’s acceptance. It’s just about the message to inspire the people around me.

People used to laugh. I have friends who used to laugh when I was using an iPhone as they were using a camera. I told them listen, I have a film camera, I have a digital camera. And I choose to do this. I was using the alternatives to represent. For example, if I was creating the McDonald’s logo, I would find alternatives on clip art to represent that logo. Not create the same thing, but create something that looks exactly like it. And I built on that. I had a huge inspiration from Kanye West when he used to use Microsoft Paint to design Yeezy’s glow in the dark when he was with Nike. Watching those things inspired me.

I come from a musical family. My mom is a gospel artist. My dad has seven albums. My grandfather was a Highlife legend in Ghana. So I had this thing where I spent most of my time in the studio. I was playing the drums and doing so many things. I was writing poetry, spoken word. I was a DJ at the age of 12. I’ve had this connection with the alternative and not totally being in the commercial zone throughout my life.

I read that you consider your work as a source of colour therapy. Could you expand on this?

I believe colour affects emotions and it changes the mood of the day. When I was a kid I used to love Wednesdays even though I was born on a Sunday because I saw Wednesday as blue. And so blue has a tranquil effect on my life. Anytime it was Wednesday, no matter what happened in school, I was super calm, super happy. I was excited to see Saturday because it was also white to me.

Also studying what colour does to people. How it affects your emotions and moods. What I’m doing with this is to help people with their mental health by creating work that they can have positive emotions from. That’s all I’m looking for. I’ve had people who had bad mental health around me. Have so many friends that go through them. I was like, how would I tackle that to heal people? Basically using colour to heal.

For a long time, Eurocentric standards of beauty have dictated how we view ourselves. However, this narrative is changing. We’re seeing a shift in perspective. What are the ways you challenge Western beauty ideals?

For me, it’s like what do I see around me? I always see my people and I always put my people first. So it’s about showing them and making people believe in themselves because we’ve been down for so long. I know people who used to say I wish I had pink lips or I wish I looked like this. And I’m like, no you’re beautiful like this. Do you know many people who try to look like you? I used to have a white friend who wanted to have the same hair that I have. We don’t need to compare ourselves to other races. You don’t need to compare yourself to other people in general. It’s about making people believe in themselves.

I believe that the prehistoric man used to draw an image of a deformed animal and show it to the wild animals and it killed their spirit. They were already defeated before the prehistoric man even attacked. If you keep seeing yourself represented in a beautiful way, it gives you confidence. It’s a psychological thing, it makes you believe in yourself more.

When Apple put those two kids that I shot on a billboard globally, it was very powerful to people. I remember a woman who lives in LA telling me that she takes her kids to school and they see the image every day and they get so excited. I want people to believe in themselves. I want those kids to believe in themselves.

I took two kids from Jamestown and made them walk for a fashion brand. When they left Jamestown, went to the event and walked the catwalk, they didn’t want to come back. They started believing in themselves, even giving themselves brand names. I’ve got a kid who’s calling himself Gucci. Because he was empowered and now the whole Jamestown call him Gucci because he believed in himself. And he was so timid. You know, I don’t think he ever believed he could be able to walk and even be on Vogue Italia. That’s what I’m looking for. To empower people. That’s what I want to do. When my mom tells me stories of how I could have ended up like those kids on the street, it makes me cherish this moment. It makes me cherish what I have and make sure I give back to them. And that’s it. I’m not trying to be rich off my people.

So amazing, I can’t wait to see your future projects

Thank you so much. And yeah, the series is not done. We’ve released more pieces in Paris because London was crazy. We have other exhibitions to serve so had to hide a few pieces for future shows. It’s very, very interesting, trust me.

Prince Gyasi is represented by Nil Gallery.