Interview: Ben Alper

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: So, for some time prior to the publication of Adrift you’ve been running The Archival Impulse on Tumblr and publishing a long series of strange and mesmerising found images. I presume they come both from your own collection and the wider web? Can you trace back your interest in found photographs and photographic archives? How do they feature in your life as a working artist?

Ben Alper: My interest in found photography began in earnest after my grandfather died in 2007. Startled by the overwhelming finality of his death, I started going through boxes of things he had possessed. I remember being surprised by how banal and impersonal so much of his archive felt. Every now and then I would find something powerful and idiosyncratic, but on the whole his effects felt somehow generic, perhaps even symbolic, like they could have belonged to any middle class American male of his generation.

It was during this time, though, that I stumbled upon a box filled with photographs, both loosely scattered and contained within albums. They were quintessential snapshots of domestic life, images that detailed expected rites of passage, vacations, birthday parties and family reunions. I was transfixed by them. However, the more photographs I looked through, the more voyeuristic I began to feel. Despite the fact that I knew many of the people and places in them, I had a strange and dislocating feeling that I was poring over the documented history of an anonymous family. The photographs were discrete, mysterious and often lacking in context. They were more iconic than they were personal, more about an idea of American life than about the specific lives of my family members. Or at least that’s how it felt to me.

This encounter led to a general fascination with, and eventually the habitual collecting of the photographs of complete strangers. When I moved to New York I would spend hours sifting through massive bins of discarded snapshots, looking for images that spoke to me in some way. I’ve never had a curatorial or thematic agenda, so my collection is quite populist, if not somewhat schizophrenic. My interest has always been more focused on gesture, convention, ambiguity, chance and cliché.

The Archival Impulse grew out of a desire to cultivate a stream-of-consciousness-like space dedicated solely to my collection. So, every image on the site is one that I possess, either in the form of a print, negative, or transparency. It’s certainly a work in progress, but my ultimate goal is for the site to archive all of the photographs I own.

My initial interest in found photographs led me to other kinds of found imagery. Crime scene photographs, as well as various kinds of instructional and institutional photography, have been of particular interest lately. And while these images have often been my source material, certain formal and conceptual attributes of the found photograph have also influenced the photographs that I make.

I can certainly recognise a comparably opaque or cryptic tone that reverberates through the photographs you make yourself, consistent with the muteness and dislocation of many of those photographs that you collect. I think from the photographic work of yours that I’ve seen it’s clear that you reject an autobiographical approach to picture-making, which opens up the really fascinating question of how your photographs might be seen by strangers at some unknown point in the future, when those images have been unmoored from your own biography…

There’s also something of that interpretive and investigative challenge at work in your book Adrift, which I think we would both agree is a powerful force in the classic book Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel. What is it that you like about the recalcitrance of the photographic image, and the kinds of opportunities it affords you to generate particular effects in your own and your archival work?

It’s the fact that photographs can so easily express a paradox between description and meaning. The bluntness of a photograph, and in particular so many of the found images I’ve collected and appropriated, is at odds with the ambiguity it so often possesses. That’s the thing that’s so compelling about Evidence, the images are as speculative as they are direct. Mandel and Sultan also effectively highlighted how malleable meaning is when images are paired together. I owe a tremendous amount to both of them, but especially to that book.

It has been an entry point for me to think about photographs on different structural terms – more akin to something approaching the structure of a written or spoken language, rather an expressly visual one. What I’m really talking about is a kind of syntax of images. You have discrete parts (or photographs) that can be sequenced or rearranged to drastically different effect. Alter the syntax and the meaning shifts alongside it. I really enjoy working in this way, because it allows for moments of surprise and transformation to occur even within a group of images that is deeply familiar.

And of course there’s something intrinsically and deeply familiar about a set of holiday snapshots found in the shape of a family album. Even as I say that, I have to of course concede that family albums and their associated social practices have been irrevocably altered by the digitisation of photography. But going back to the book Adrift, could you talk us through the genesis of the work, and the ways in which you were able to engage familiarity and estrangement in the collection and editing of these pictures?

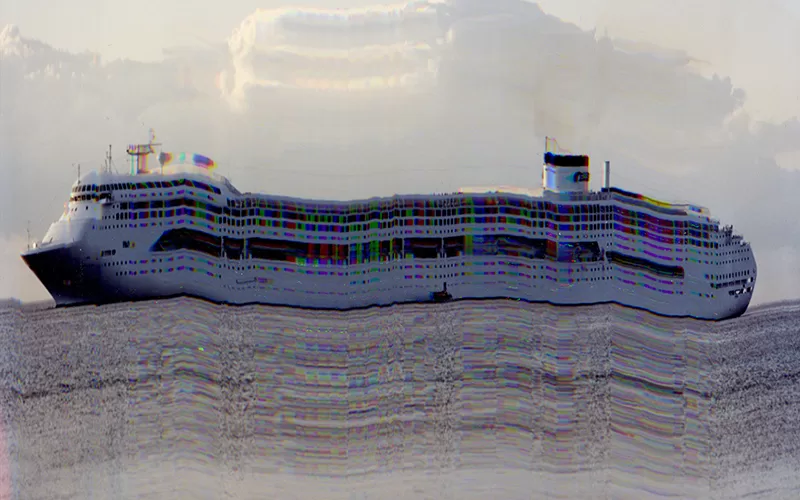

Adrift grew somewhat organically out of a grant that I received last summer. In my proposal, I wrote about expanding an earlier project entitled Background Noise, which had always felt frustratingly unresolved. In that work, digital aberrations coalesce with both found and family photographs. I wanted to raise questions about the manner in which personal photographic histories are now archived and recalled. And a large part of that revolved around exploring issues of materiality in our widely digital age.

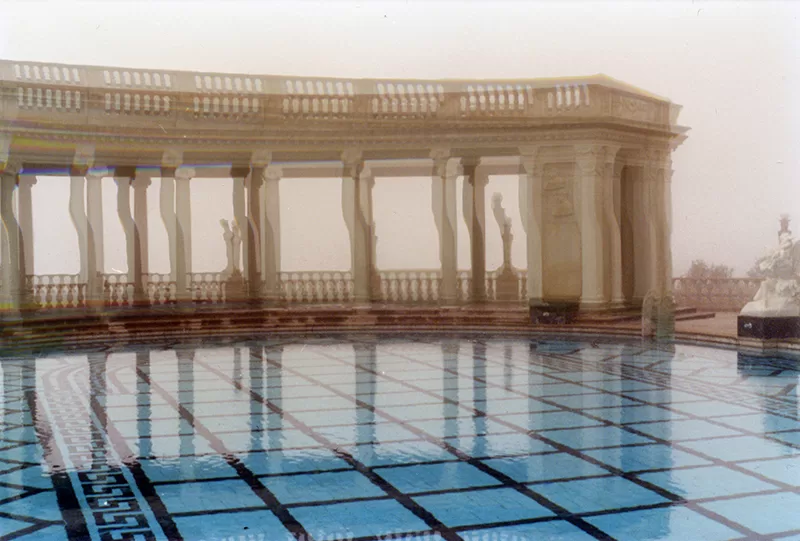

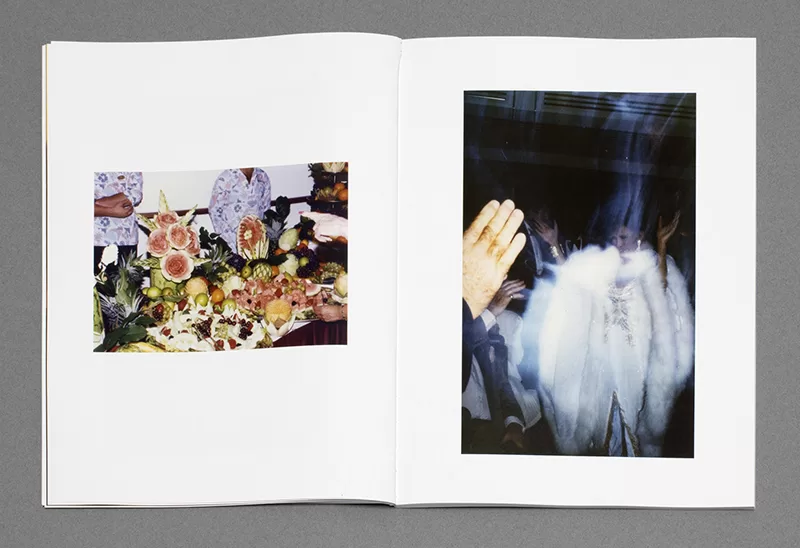

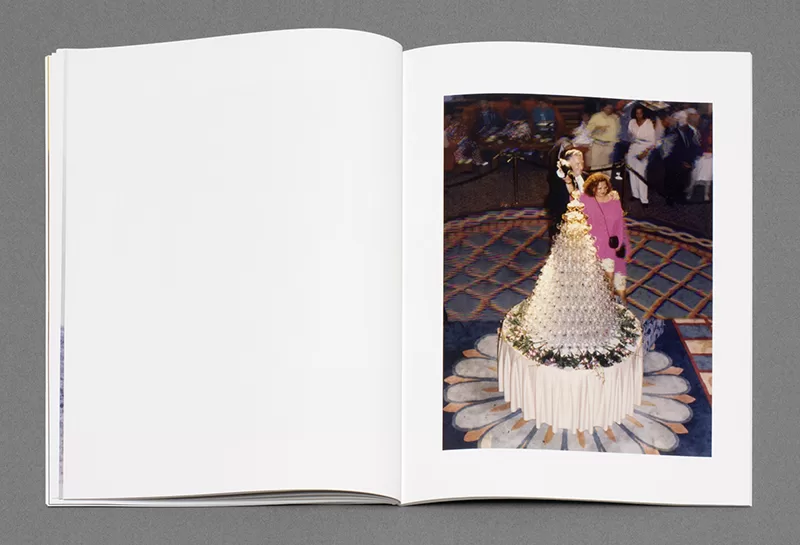

However, at the time that I applied for the grant, my conceptual interest in found photography had shifted somewhat away from issues of materiality and more toward the possibilities offered by an ambiguous approach to narrative. I knew that this would be heightened by finding and appropriating an archive that was intact, where the images were fundamentally linked by time, place and the people who inhabited them. So I looked through the few complete albums I had and eventually decided on a group of photographs of two men on a 1990’s cruise vacation together. I had always wanted to do something with the images, but had never found an appropriate form for them. They were also far more contemporary than the majority of found photographs I owned, which interested me.

What struck me was that the two protagonists were both so young, and the photographs so recent, that it made the dislocation feel somehow more acute and evocative. I thought a lot about the life and trajectory of the album. What had set it into motion, away from its history and context? I came to see it as a kind of “message in a bottle” — a cryptic transmission from a discrete time and place, adrift somewhere between a point of origin and its final resting place . This idea of being adrift, or in limbo, would become the guiding conceptual framework for the book. And it wasn’t until later, shockingly, that I realized that the narrative content of the images, the cruise, was the perfect visual metaphor for this. The imagery literally depicted both people and ships drifting in the ocean, suspended in a perpetual in-between space.

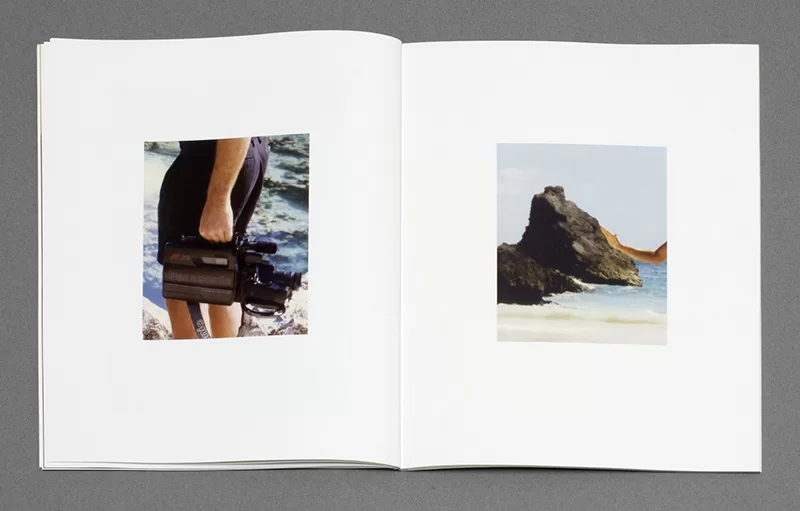

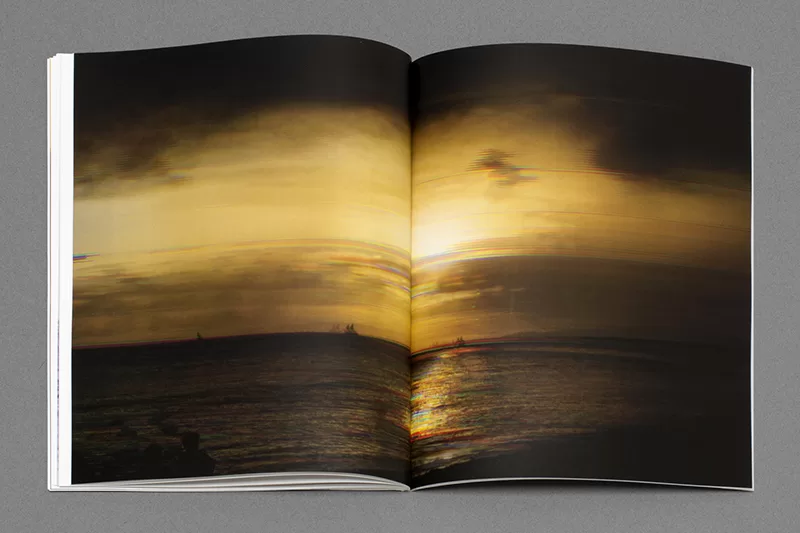

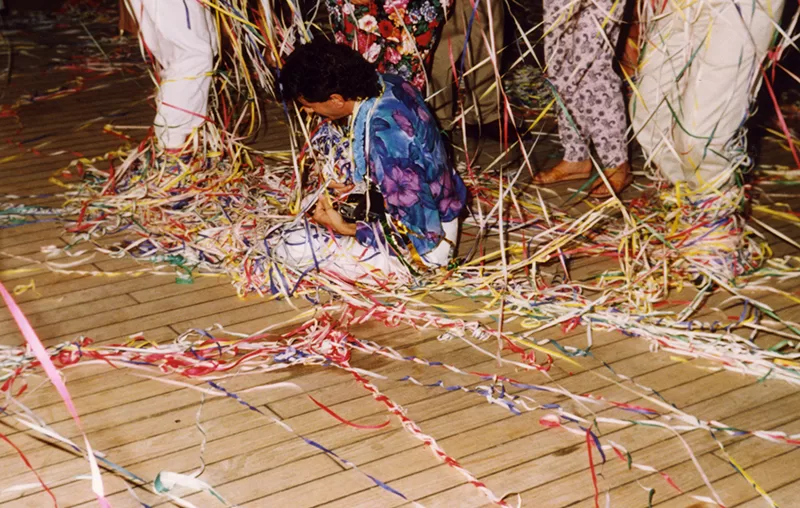

This motif guided many of the decisions related to both the making of the work, as well as the eventual editing and sequencing. I wanted there to be both a sense of deep familiarity and also of alienation. The familiarity was easier to distill, namely because snapshots (and particularly those documenting vacations) are so ubiquitous. I also focused on certain photographic tropes that recurred throughout the album: sunsets, poolside portraits, hands appearing to hold up huge rocks (the result of forced perspective) and underwater snorkeling images of exotic fish. These types of photographs are so common, and in certain cases cliché, that they act as a form of visual shorthand. We feel like we know them already because they are part of a lexicon that is pervasive.

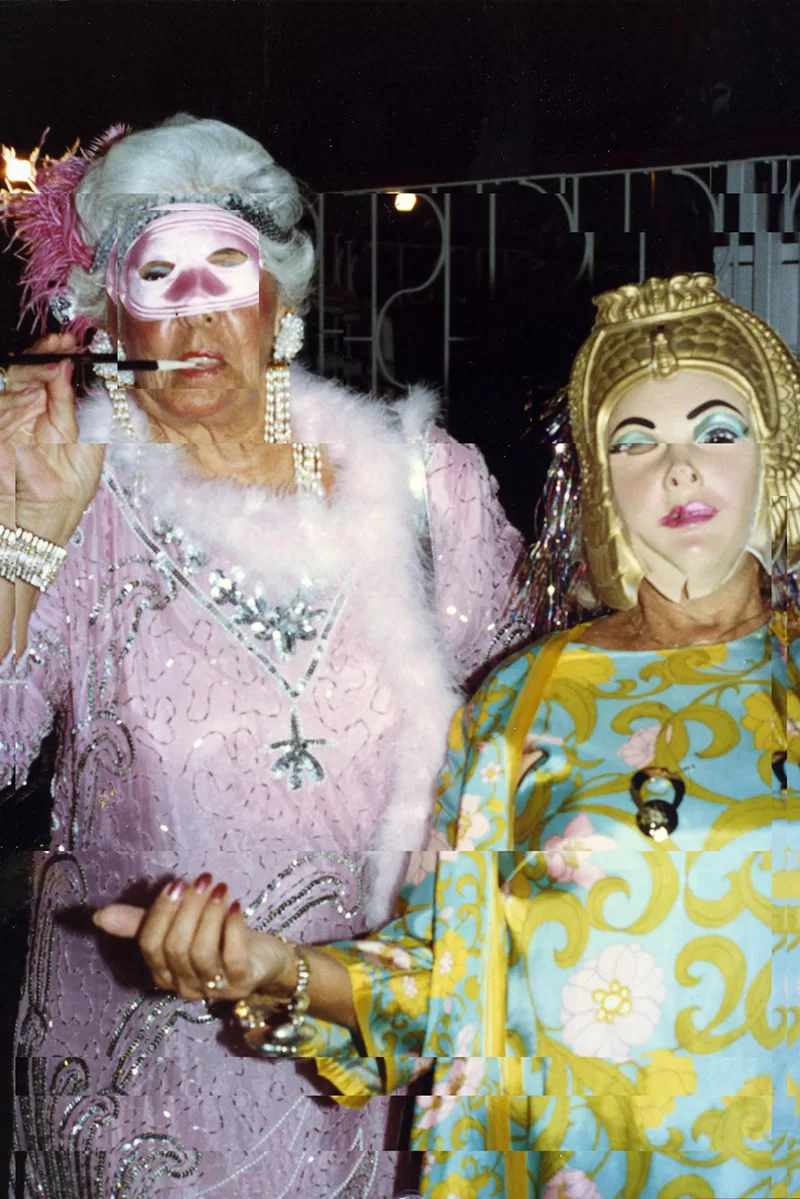

It was important to me though that the familiarity be undercut by conflicting feelings of displacement and isolation. So I turned to a handful of different formal strategies to try and evoke this. The first, and perhaps most significant, is that two central characters in the narrative, the two young men that recur throughout the book, are never seen together in any of the photographs. Even when it is implied that they once existed in the same image, as in the pair of portraits where they are both out of focus against a background of focused ferns, they occupy separate frames. Other figures in the book are also compartmentalised and alone. When people are seen together, often the majority have been obscured with digital noise, leaving a solitary, unmanipulated person to stand out in sharp relief. I wanted there to be a slightly uncanny feeling to the work, the kind that is born when familiarity gives way to strangeness. The physical space that the narrative exists in approximates one that we know, but is ultimately eclipsed by one that is distinctly more metaphorical and psychic.

Certainly one of the very notable things in this book is the overt manner in with which the pictures suggest the specificity of your own narrative focus. Many of the photographs appear far too narrowly cropped to be typical of a family photo album, and of course others as you say have been ‘filtered’ in some legible but strange way. There’s something nuanced and complicated that develops through the book as we realise that Adrift isn’t about the people who made or who appear in the photographs, but rather about the life of the images and the album itself. The book comes to be about the ways in which that irretrievable event, and those unnumbered lives are refracted back to us through the anonymous distance of these pictures. It seems to outline something of a tender but bleak prognosis for all our Flickr albums and Facebook photographs…?

You’re right to point out that Adrift really isn’t about the people in the photographs. In this particular case, the histories and narrative contexts at play in the images were so impenetrable that any inclination toward fidelity would have simply been conjecture. So it made sense to initiate this work from a place of invention and speculation. A number of my projects that integrate found photographs exist in an entirely fictive space, one that speaks more to my own narrative desires and interventions than it does to the actual subject of the image. And I think it’s important that the work reverberates back to me in discernible ways, because there is a particular kind of voyeuristic looking that is fundamental to working with this kind of material. Honestly, at times I still question my appropriation of these deeply vulnerable and personal images. I was certainly never the intended audience, but nevertheless, through a mysterious and likely random chain of events, these photographs have ended up in my possession. And I don’t take that lightly. However, sometimes a conflict manifests between feeling like my appropriation is a form of resurrection, but also somehow a violation. This is particularly true in the images that are mediated. The interferences often read like digital scars that violently mark the surface of the image.

Ultimately, Adrift is, in some oblique way, autobiographical – in that it expresses certain anxieties that I have about the testimonial power of all photographs. And despite the fact that I generated this body of work from an album of physical prints, there are certainly cautionary undertones in the book that point to the tenuousness of digital images. In many cases, the scanner aberrations intentionally destabilise the integrity of the image. My hope was that these sites of tension would act as visual metaphors for how digital photographs have, in certain fundamental ways, displaced tactile ones.

As I write this I’ve just finished listening to the panel discussion from the event Everyday and Everywhere: Vernacular Photography Today held in London in November of 2013. In it, a good deal of emphasis is laid on the hierarchical relationship between art photography and ‘vernacular’ photography as categories. At one point Geoffrey Batchen explains the constancy of the trope of sunset imagery as linked intrinsically to our apprehensions of mortality, and I think that notion can be tied back in interesting ways to the inevitable obsolescence or anonymity our own personal images (digital or otherwise), and to our work as artists over a long enough span of time.

Those of us collecting and publishing these anonymous photographs are taking up and reconfiguring the shape of personal histories from which we’re deeply disconnected, and in the same way that a sunset prefigures our own mortality, so too do these archives prefigure our own evanescence as image makers. There’s a kind of reflexive memento mori at work in those instances where image makers delve into the wider anonymous image stream.

What are your thoughts and concerns about the extent to which the appropriative gesture mimics the instinct for making the sunset picture, by temporarily holding in place our existence against a horizon in which our own images will inevitably be subsumed?

I want to be cautious not to make any generalized assertions about why people collect and appropriate photographic images, because, like any behavior, the motivations that underpin it are nuanced and complex. It’s a process that I can really only speak to from a place of idiosyncrasy. That being said, I think Batchen’s reasoning for why people continue to perpetuate the sunset photograph only accounts for one possibility among many. I believe people photograph sunsets for a multitude of reasons. Perhaps for some it is an attempt to keep mortality at bay, while simultaneously acknowledging its eventuality. For others though I believe it’s more a form of pantomime, an internalized gesture or learned behavior that articulates a sentiment that is both ubiquitous and commercial. However, I think the dominant reason that people photograph the sunset is not because they are afraid of dying, but rather because they are afraid of forgetting. In an interview, Milan Kundera once said that “forgetting is a form of death ever present within life.” This is certainly related to Batchen’s claim, but it’s also distinct. The loss or displacement of memory is particularly anxiety-producing because it often occurs against a backdrop of consciousness. We know that we’ve lost something, which makes the pain that accompanies it all the more acute.

And while a preoccupation with forgetting has admittedly been a catalyst for many of the photographs I’ve taken, it hasn’t been for those that I’ve collected. Which is perhaps strange, in that nearly every print, negative or slide that I own is by its very nature a memento mori. They are all persistent reminders that, one day, we too will exist solely as traces in photographs. However, there is something about the anonymity and depersonalization of the images, their complete lack of connection to my own history, that affords them the ability to embody other things. For me, collecting vernacular photographs has always, first and foremost, revolved around my love of the medium. It has laid bare how wonderfully (and frustratingly) ambiguous and contradictory photographs can be; how pliable they are in regard to narrative. Collecting has also brought out in me an appreciation for photography’s tropes, formalities and accidents. When I first started, my interests were much more ethnographic. I would separate the pictures according to whether they were in color or black and white, and would then classify them by type. I was interested in cultural behaviors and conventions that were repeatedly echoed in photographs, much like the sunset picture. However, the images always seemed to defy compartmentalization. More recently I have abandoned these constraints and found myself drawn to looser, more associative kinds of connections between images – ones that are perhaps less intuitive, but that feel imbued with greater poetic possibilities.

In the end, I see my appropriative gestures less as ruminations on death and more as attempts to resurrect, or breath new life into, images that have been laid to rest. It could certainly be argued though that this process only further decontextualizes the image appropriated and signals a new kind of symbolic death. So, perhaps, in some intrinsic way, a discussion surrounding mortality cannot be evaded.

Your emphasis on memory and forgetting reminds me of David Campany’s essay on Stan Douglas, “The Angel of History in the Age of the Internet”, where he begins with Walter Benjamin’s fascination with the idea that histories are not permanently intelligible and accessible. Something I’m captivated by in the images in Adrift is the near-pastness, their youthful antiquity if you like – and the extent to which, even as we note their period style, we’re reminded of the resuscitation of those fashions in the contemporary moment… How did the pictures make you think about time and the present?

As I mentioned before, one of the main reasons that I wanted to work with the photographs in Adrift was specifically because they were substantially more contemporary than anything else I had collected. I remember feeling an unexpected closeness to the two protagonists when I first discovered the album. A sticker in the back dated the images to 1991, and being that that they were likely in their mid-to-late twenties when the photographs were taken, I estimated that they were probably only 15 years older than me. These two men were very likely still alive, and if they weren’t, something had gone terribly wrong. More often than not when I encounter vernacular photographs, the subjects in them are almost certainly dead. This creates a distancing effect, which in turn promotes an emotionally remote viewing experience. However, the Adrift pictures felt different. For one thing, the bridge between the original photographic event and the present moment was much shorter, and thus felt more compressed. Additionally though, there were also deeply familiar cultural and aesthetic markers that ran throughout the images – clothing and hair styles, interior decoration, car design and the photographs themselves. The glossy, full bleed c-print was the dominant photographic form of my childhood, so while flipping through the pages it was easier to imagine that I was looking through an album of my own.

The relative recentness of the images also activated a more expressly narrative dimension in me. I thought a lot about what might have happened to these men and envisioned a variety of scenarios for different kinds of relationships they might have had. I am still ambivalent about what the nature of their relationship truly is (or was). They could just as easily be brothers, friends, or lovers; at different times I thought they were each of these. I wondered whether there had been some kind of estrangement between them. Perhaps the experience, and in turn the photographs, existed as a reminder of something unpleasant or painful, and the album had been discarded as an act of repression. Or perhaps the reason was more circumstantial. It seemed conceivable that one of them had died, or moved, or simply forgotten the album along the way. There is no way to know. What is clear though is that these photographs have a very different relationship to the present than the vast majority in my collection, precisely because so many of the subjects are likely still alive. It makes the loss somehow more incomprehensible, more psychological.

The other thing that feels significant is that these photographs were made in 1991, the year that Kodak released the first commercially available DSLR. I didn’t realize this until the book was almost complete, but there is something poetic about this connection, being that one of my conceptual aims was to address our continually shifting relationship to personal photographic archives today. The album was made physical during the year that photographs were becoming increasingly ephemeral. And if a sunset prefigures our own death, then this album, in some analogous way, prefigures its own obsolescence. The more I thought about this, the more present the photographs became. They entered the world at the threshold of a profound paradigm shift. And while I think it’s easy (in retrospect ) to see them as artifacts, even at the time they were printed, I also view them as symbolic harbingers that ushered in a new and tenuous form of image-making.