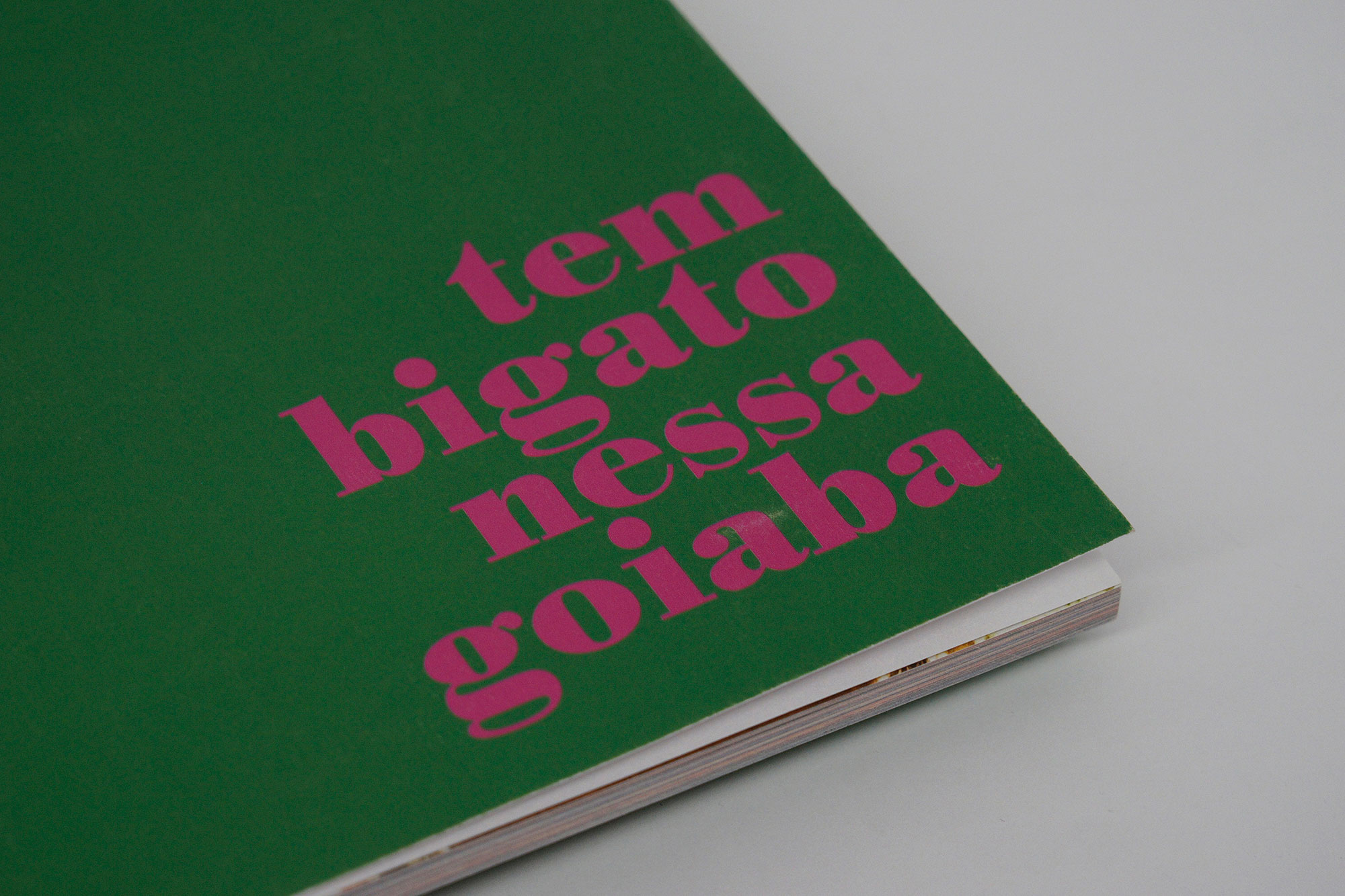

Interview – Cecilia Sordi Campos: Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba

After migrating to Australia and the break-down of her marriage, Cecilia Sordi Campos desired to re-connect with her Brazilian heritage. Heavily influenced by the Anthropophagic Manifest by Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade, Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba represents the need Campos felt “to devour my Brazilian influences, my hybrid identity, and my emotions to then transform them into a new form of expression.”

Recently awarded with a Photobook Commendation at the Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award, we spoke to Campos about how the project acted as a catharsis, the recurring themes and symbols that appear throughout the work, and the search for a new identity.

What does the title, Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba, mean to you?

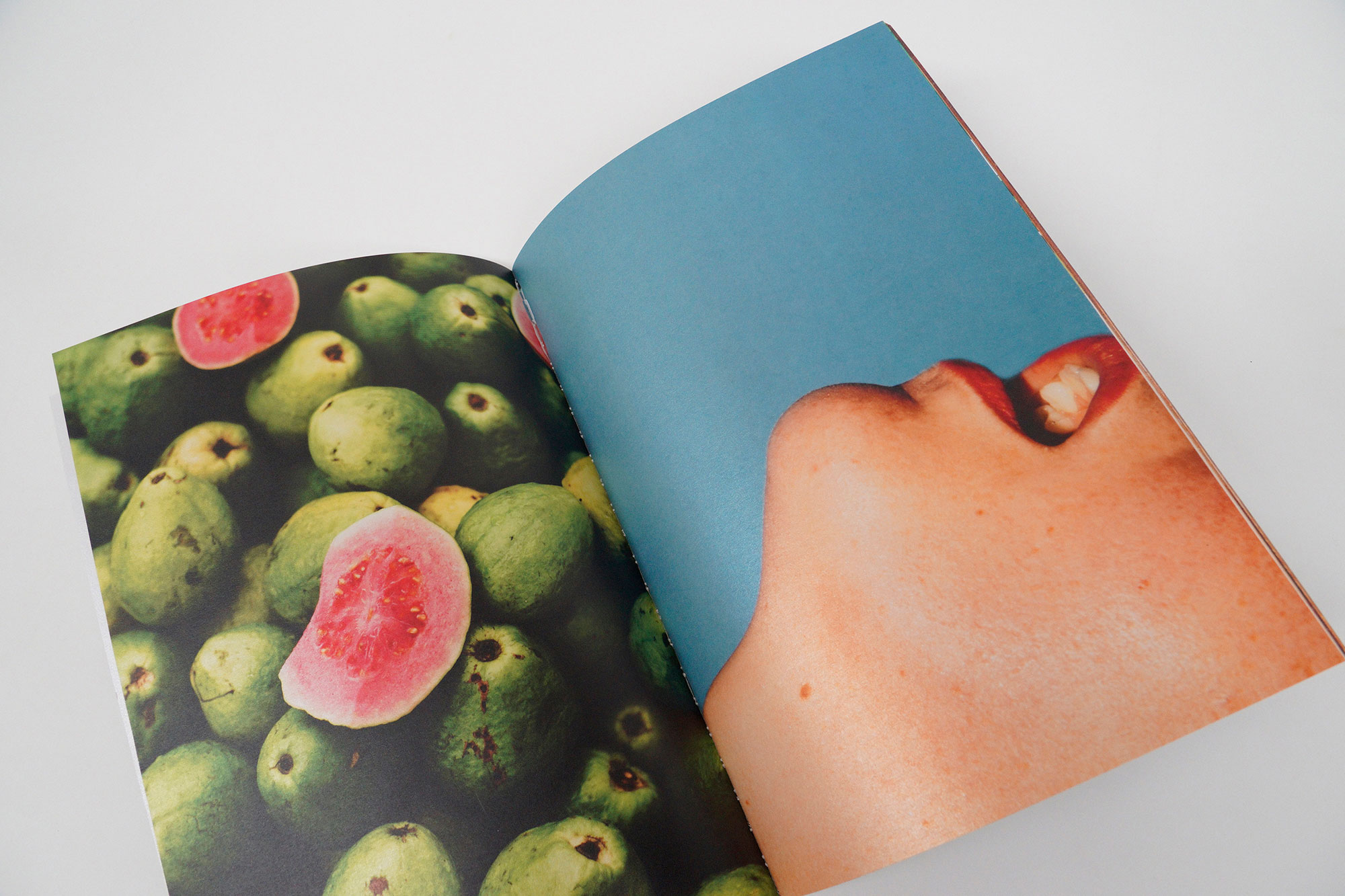

The title Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba, which roughly translates from Portuguese to English to There are Maggots in this Guava, alludes to my childhood memories in Brazil of stealing guavas from people’s trees. The expectation of cracking the guava open and the possibility of finding maggots inside was more exhilarating than eating the fruit itself. The title also serves as an aphorism for the period following the separation from my husband of 10 years. Once I recognised the dynamics of my relationship with him were, in fact, volatile and abusive, I left him. A very emotional period succeeded, and during this time I began to find exhilarating moments of pleasure and joy in the banal.

You have mentioned that Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba is influenced by Anthropophagic Manifest (Cannibal Manifesto), by Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade. He argues that cannibalism became a way for Brazil to assert itself against European post-colonial cultural domination. How did the manifesto influence this project?

I have had an unhealthy obsession with the Manifesto since I first studied it during high school. I have also been obsessed with Tarsila do Amaral, a Brazilian modernist painter who was married to de Andrade at the time the manifesto was first published. A drawing of her most famous painting, Abaporu, illustrates the cover of the manifesto’s first publication.

De Andrade’s poetic text was inspired by a Tupinamba ritual, in which the Tupis – the largest Indigenous peoples of Brazil before colonisation – practised eating their enemy, supposing they were thus assimilating their strengths. In the manifesto, de Andrade proposed to ‘devour’ the cultural European, as well as Brazilian influences and customs. Once these influences and customs are devoured, they are then transformed into a new form of expression, or aesthetic revolution, for the modernists to rediscover a Brazilian reality. In other words, the anthropophagy in the provocative manifesto is a constructed metaphor for a more engaged representation of the process of cultural hybridisation.

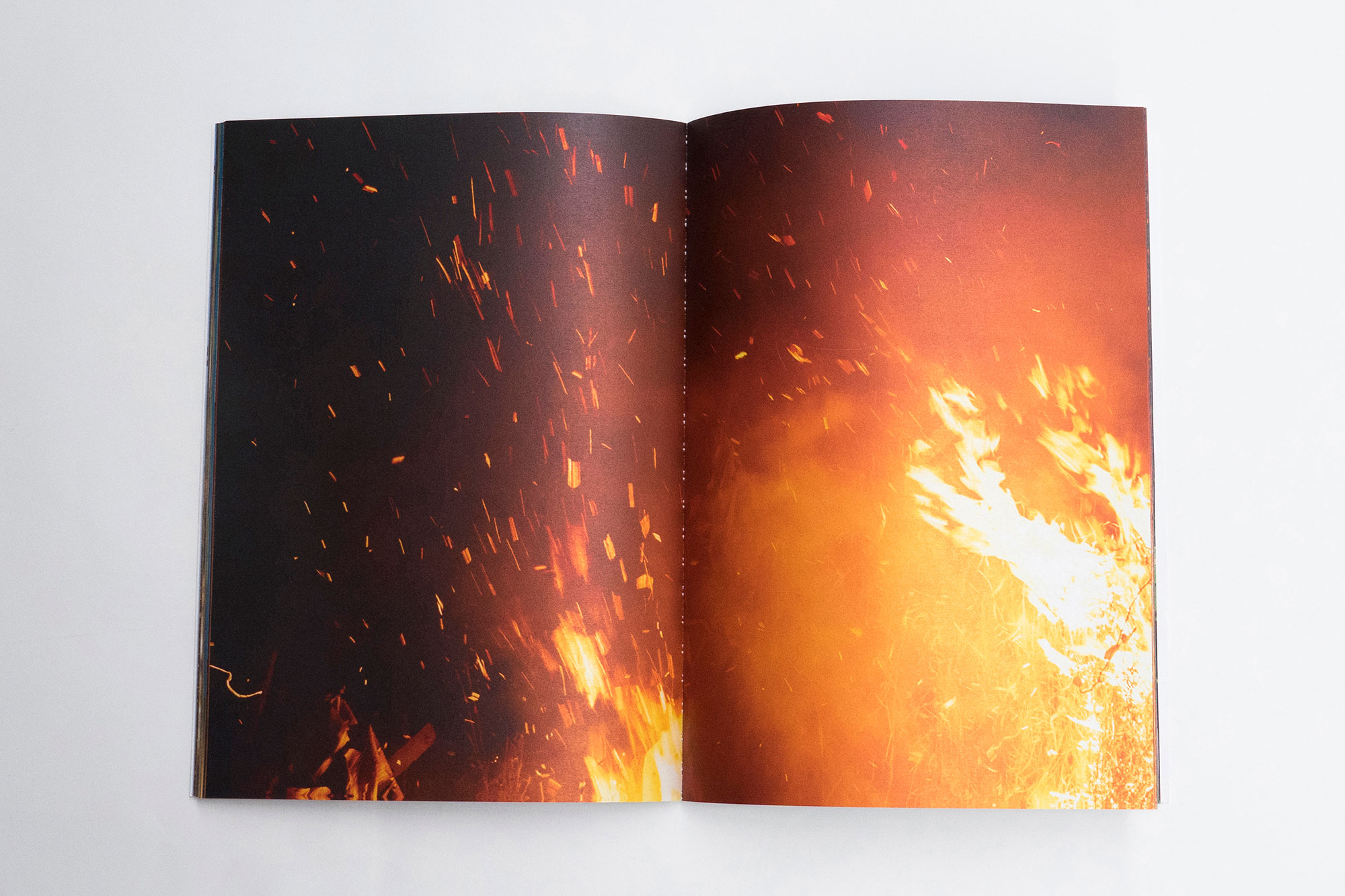

The Cannibalist Manifesto served as a metaphor or Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba, as it represented the need I felt to devour my Brazilian influences, my hybrid identity, and my emotions to then transform them into a new form of expression. Driven by it, I aimed to develop a metaphorical language for the visual body of work. I used repetition of images of fire and disembodied self-portraits as a method through which to bring attention to the hyperbole of the devouring of the self.

Through the making of this work, I assert my Brazilian heritage and embrace my hybrid identity, wherever I may be.

Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba was produced as a way for you understand two major consecutive life events; relocating from Brazil to Australia and the break-up of a long-term relationship. Given the recurring themes that appear throughout the book; young/old, life/death, it seems you are coming to terms with a new way of being, of figuring out where you stand in the world. In what ways did this project act as a catharsis?

My migration to Australia happened around 13 years ago. I was quite young, extremely naive and did not speak any English when I first arrived. I came to Australia to help a family member and stayed for love, as cliché as it sounds! Nonetheless, it was my choice to stay in Australia. I have always felt deprived of a sense of identity and a place of belonging, both geographically and metaphorically.

Through the research and making of this project, I aimed to explore what constituted my identity, as I had become quite alienated from Brazilian culture whilst married. As a migrant, I believed I had to conform, albeit unconsciously, to attributes imposed on me or to a more “Aussie” lifestyle. As I began to forget my mother tongue, I recognised that I was removing the last part of me that had any connection to my Brazilian identity.

I lived in a rural town for the most part of my life in Australia. I became extremely attached to the land; I fell in love with it, hoping it would love me back. When my separation happened and I had to move from the land I loved, I felt stripped from home once more. Upon reflecting on my own emotions, parallels between my migration and my separation were established; the deprived senses of belonging and identity began to be exceptionally reoccurring. The layers of what I believed also constituted my identity began to rupture. I was no longer a wife and had once more entered a state of in-between; single, yet, still legally married.

It was through the research and the making of Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba that I began to question and embrace the layers that constituted my identity, as well and the interiorising of the longing I felt for the concept of home. Through the making of these and the moving images, I perform a cathartic ritual that allows me a means of emphatically throwing the past into the flames, and evoking my origins in a new geographical and cultural setting. Through the making of this work, I assert my Brazilian heritage and embrace my hybrid identity, wherever I may be.

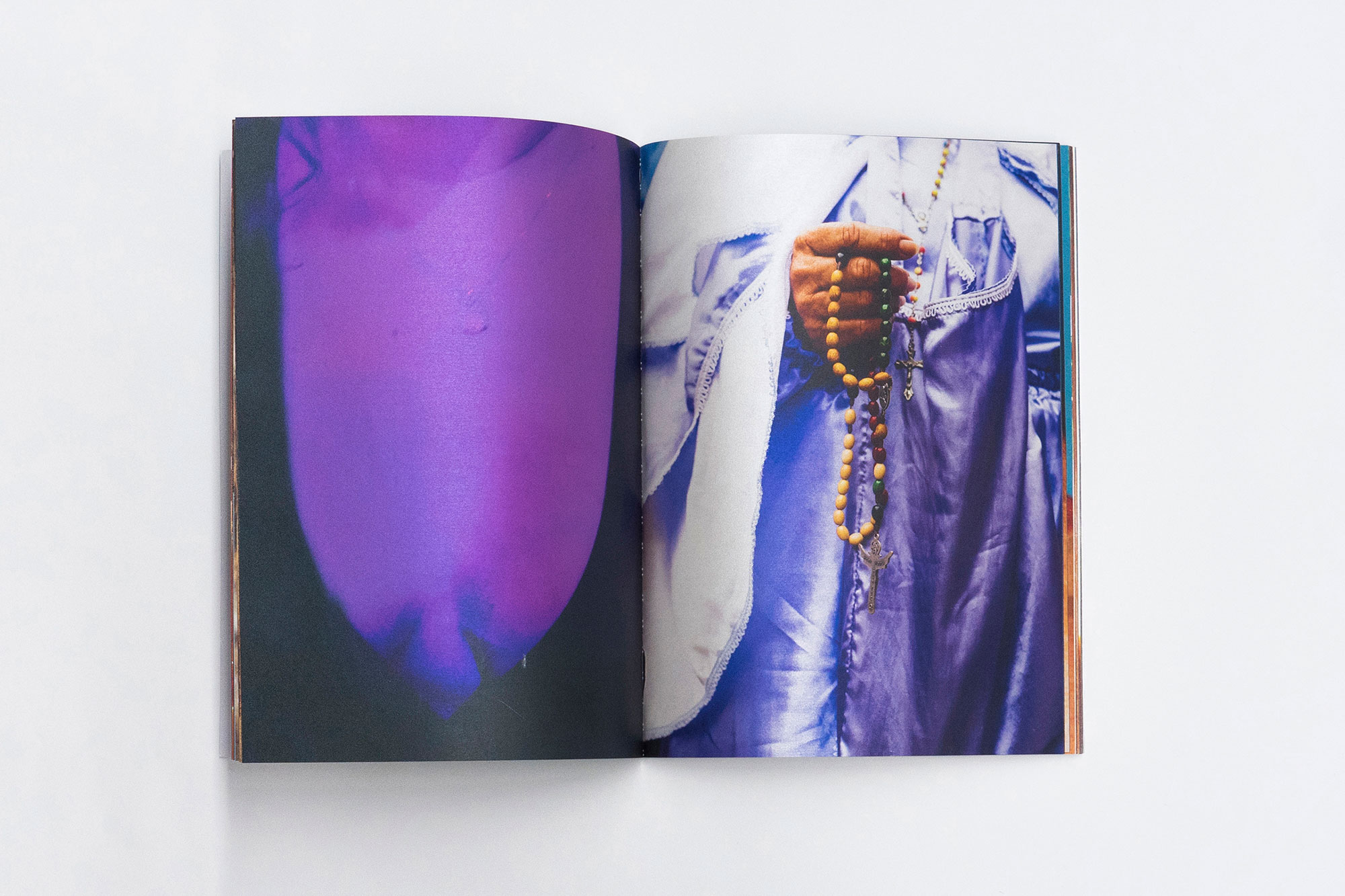

Rosemary beads, the crucifix and religious icons are just some of the symbols that reoccur within the book. What do these symbols represent? What role does religion play in your life?

I grew up in a very traditional Catholic family in Brazil. Growing up, I performed customary catholic rituals and attended mass every Saturday. Whilst religion in Brazil is extremely diverse and is characterised by syncretism, the Brazilian population is still overwhelmingly Christian, most of whom are Roman Catholic. I am no longer a practising catholic; nonetheless, I am still attracted to catholic icons, imagery and customs.

When I discovered my paternal grandfather, purportedly catholic, was in fact secretly involved with Umbanda – a Brazilian religion marked by a strong syncretism between Catholicism, Spiritism and Afro-Brazilian religions – I became fascinated with the story and it led me to an exploration of what constituted having a spiritual practice, as well as the exploration of my beliefs and unanswered questions surrounding religion.

While I do not consider myself religious, I do maintain a high, and extremely private, spiritual practice. It could be defined as being hybrid and fluid, and it is definitely imbued with syncretism. Paradoxically, when I’m back in my hometown, I attend both mass and Umbanda rituals. In the book, the recurring religious symbols directly reference the parts of me that are still fascinated by catholic rituals. There are also more subtle recurring themes that also reference the hybridity in my spiritual practice; some of these are not as recognisable to the viewers, however, they carry ritualistic symbolism.

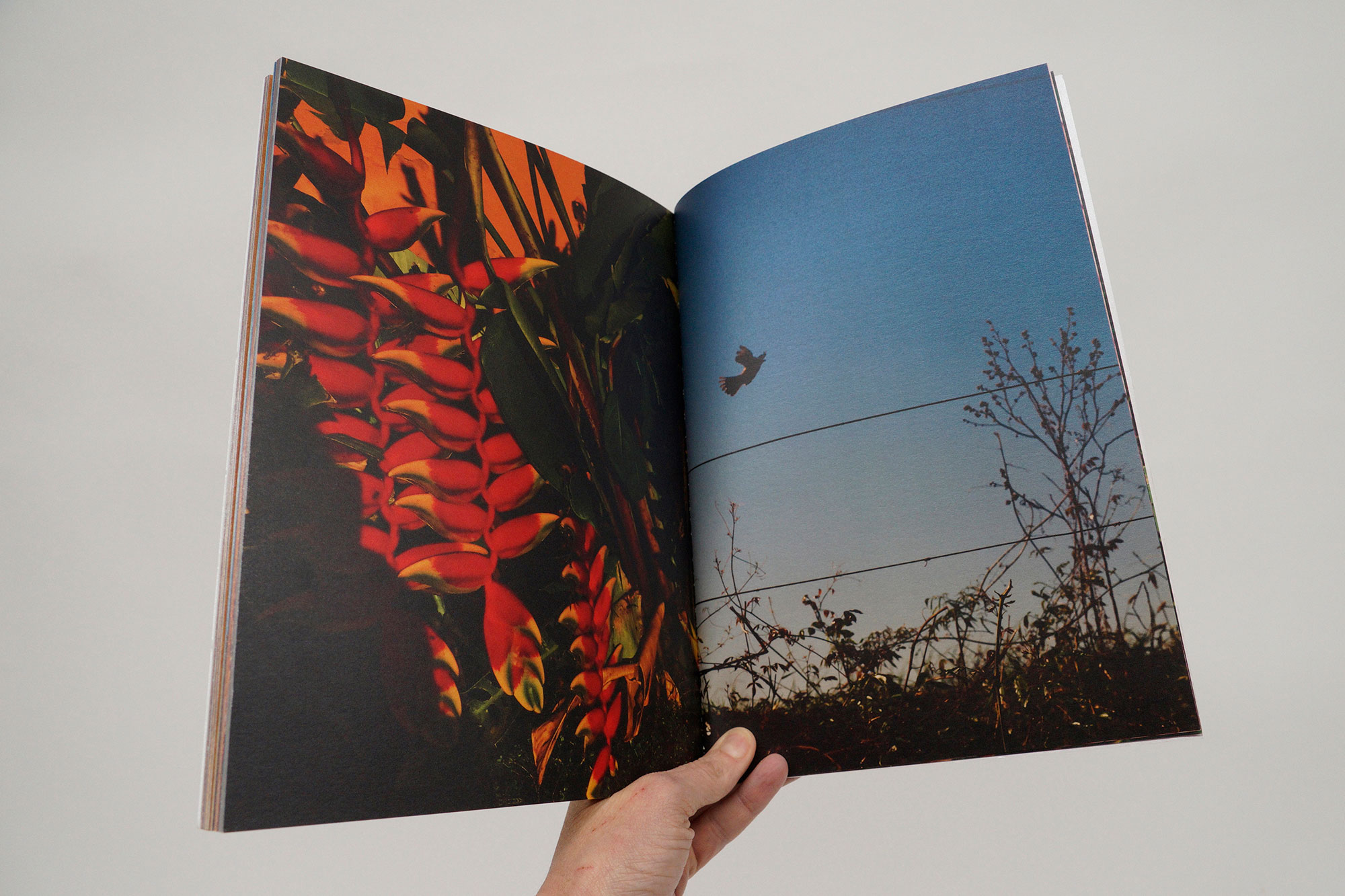

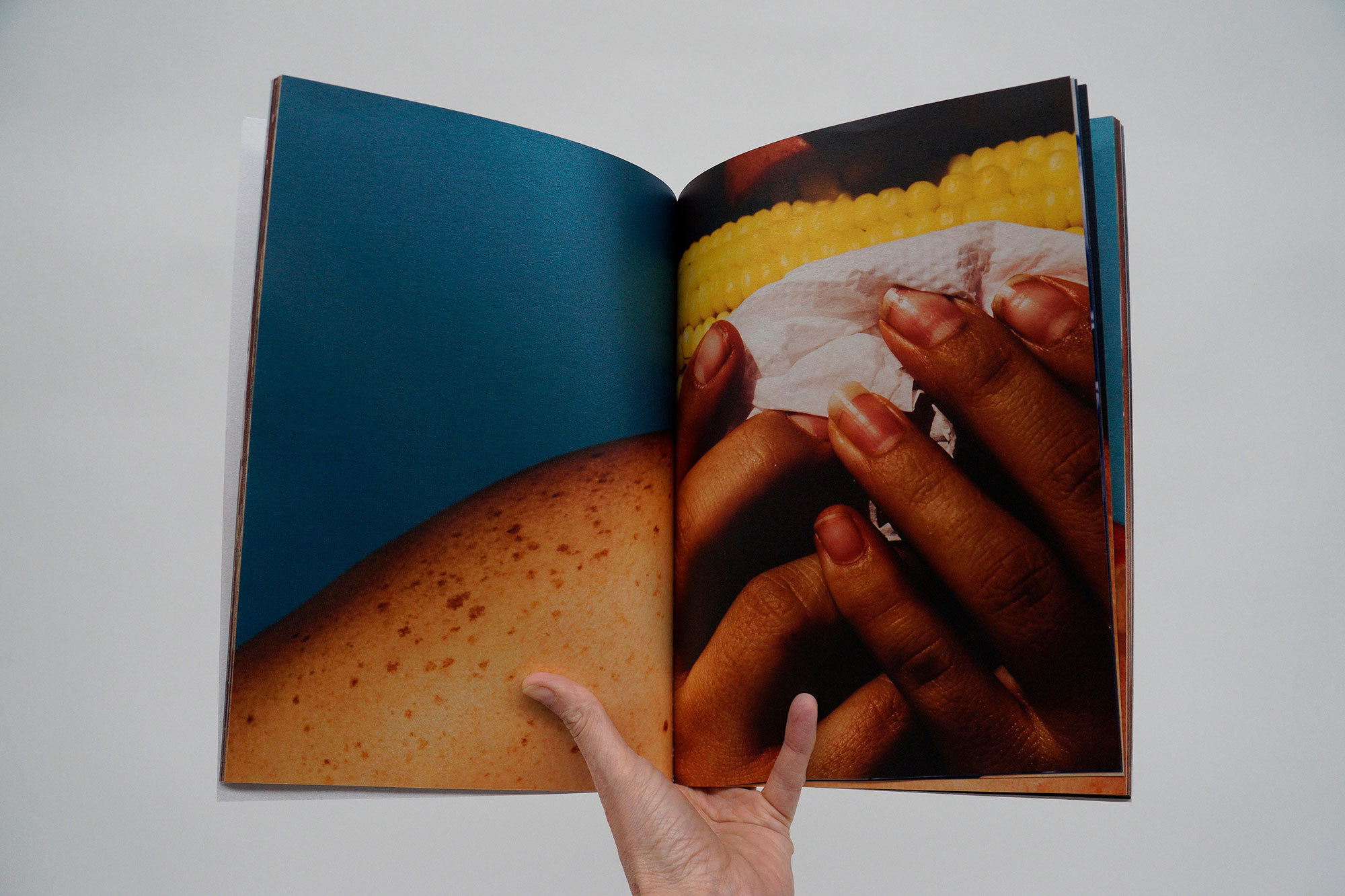

The book is filled with full-bleed, tight crops; images that are juxtaposed, sumptuous; a sense of chaos and of calm. A close up of a rotting fish sits next to an image of a bare chest; a couple dancing next to an image of an elder’s ear. Can you talk a bit about the design of the book and your editing process?

The book is sequenced in the form of a non-linear narrative that reflects my intention for the work; a collection of uncensored perceptions of my being seduced and ultimately falling in love with my birthplace once more. The erotic imagery also represents the liberation and embracing of my sensual self from the confines of a constricting and emotionally abusive marriage.

I also aimed to borrow from aspects of Brazilian music Carnaval and Samba. The sequencing of the images is loosely based on mimicking the batuque, or drumbeats in the samba cadence. However, the images in the book can be identified by their own erotic rhythm, by the throb of alternate emotions and contentment.

Through the book, I wanted the viewer to experience an effect of jouissance, which has become the manifestation of existence generated by photography, which at the same time generated photography itself. The book does not respect a timely or themed ordering of images. Nonetheless, I share with viewers the disorders, choices and metamorphoses that have allowed me to simply live during this period of emotional transition. The use of full-bleed and tight cropping aimed to serve as provocation and stimuli that deconstruct notions and customary ways of thinking.

All images and spreads Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba, Cecilia Sordi Campos (self-published, 2019), courtesy the artist. You can purchase a copy here.

View Tem Bigato Nessa Goiaba in full on the Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award site.