Interview – Cherine Fahd: Apókryphos

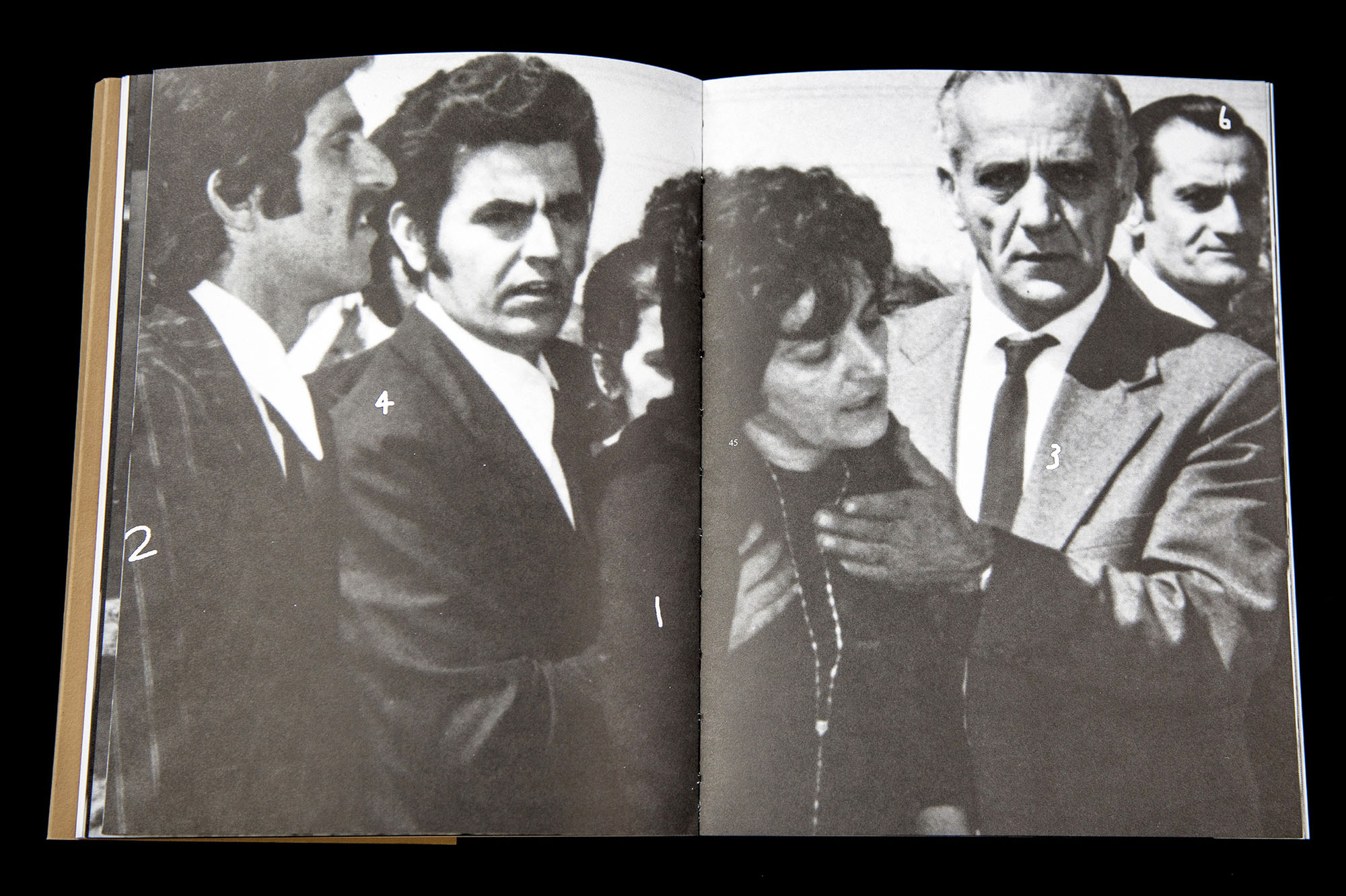

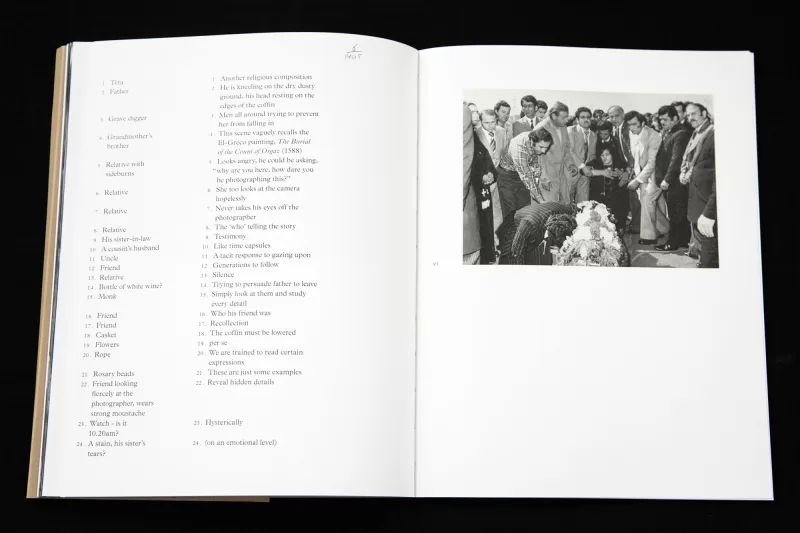

In 2010, Cherine Fahd‘s paternal grandmother gave her a box of photographs. Whilst rummaging through familiar family photos; weddings, birthdays, Christmas’, she discovered, tucked away in the bottom of the box, a brown envelope with 24 black-and-white photographs; photographs of her grandfather’s funeral and burial which had remained hidden since 1975. Overwhelmed with emotion, Fahd decided to hide them away once more, this time under her bed where they remained for the next seven years.

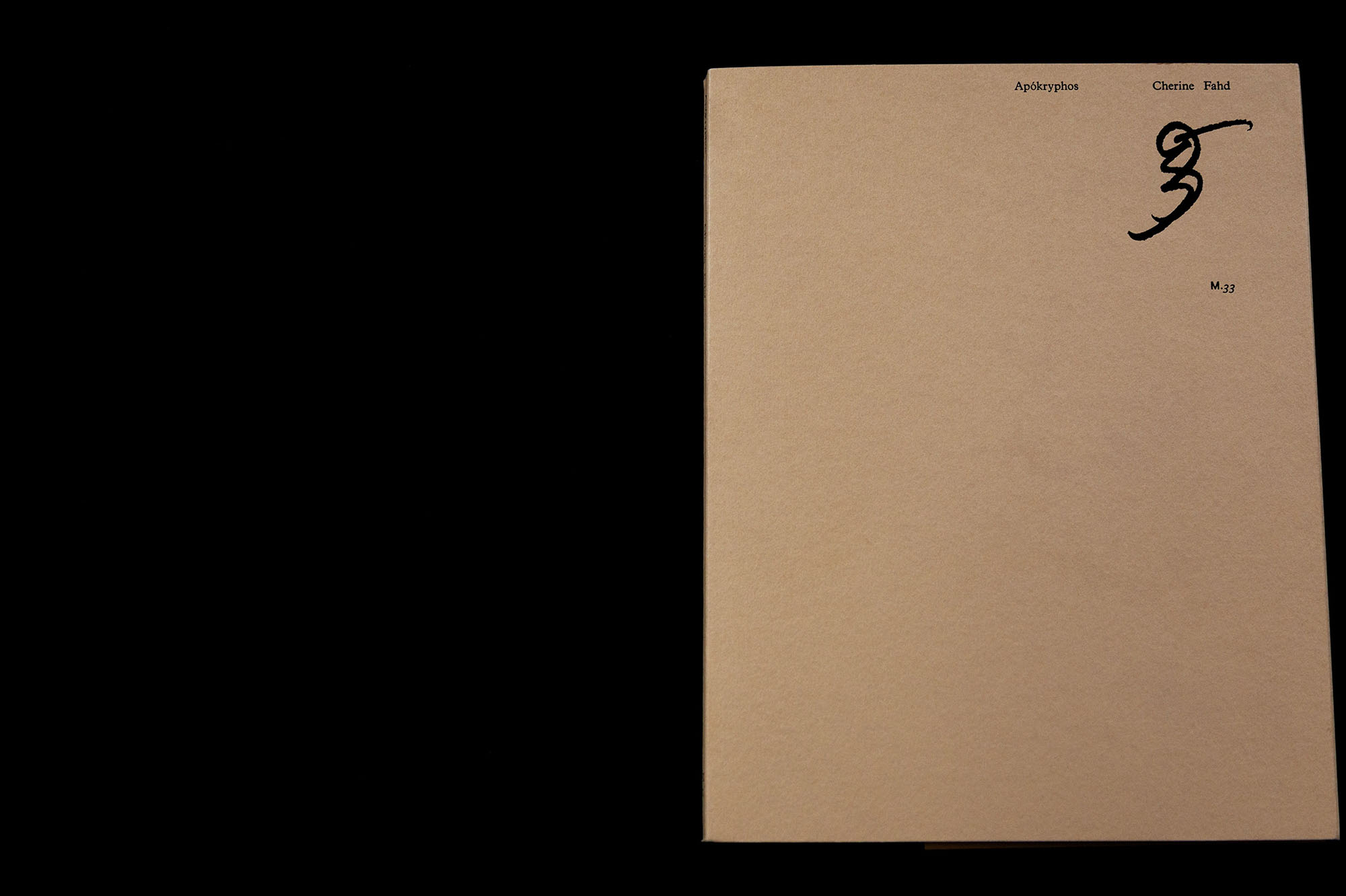

The photographs have since been reproduced and exhibited both at Carriageworks in Sydney and Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne, as well as in Fahd’s photo-text book titled Apókryphos (M.33, 2019), which won photobook of the year in the recent Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award.

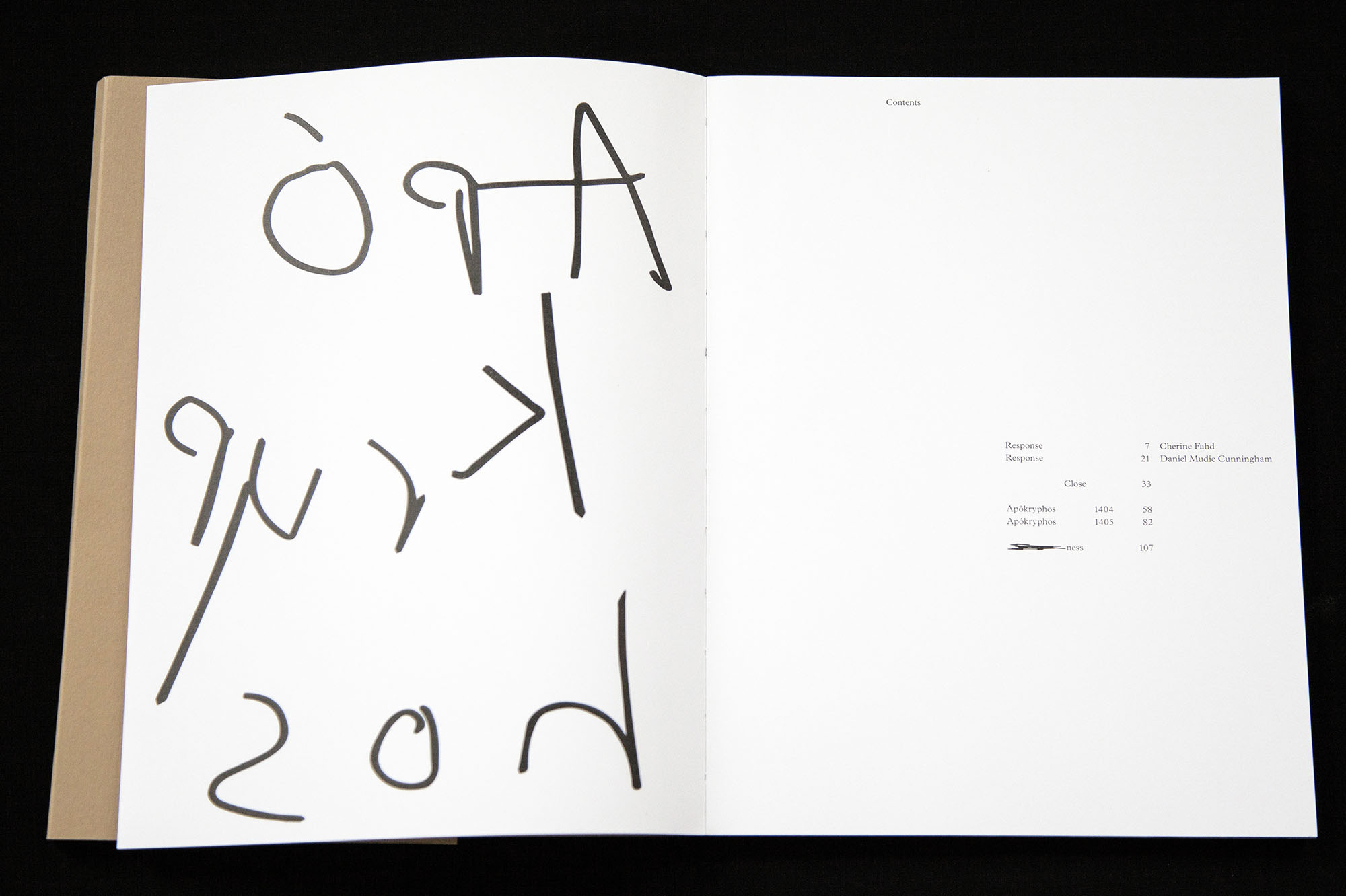

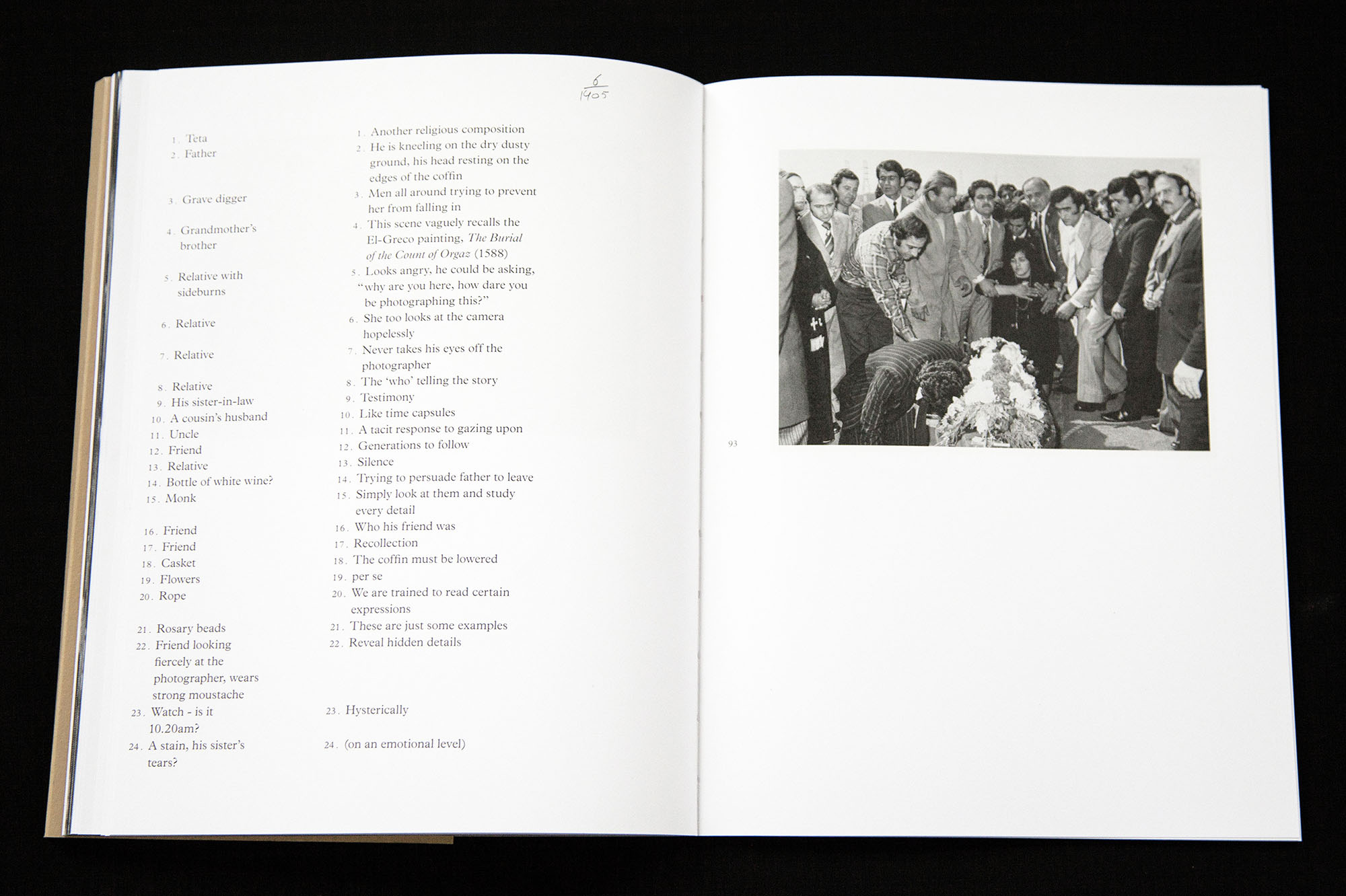

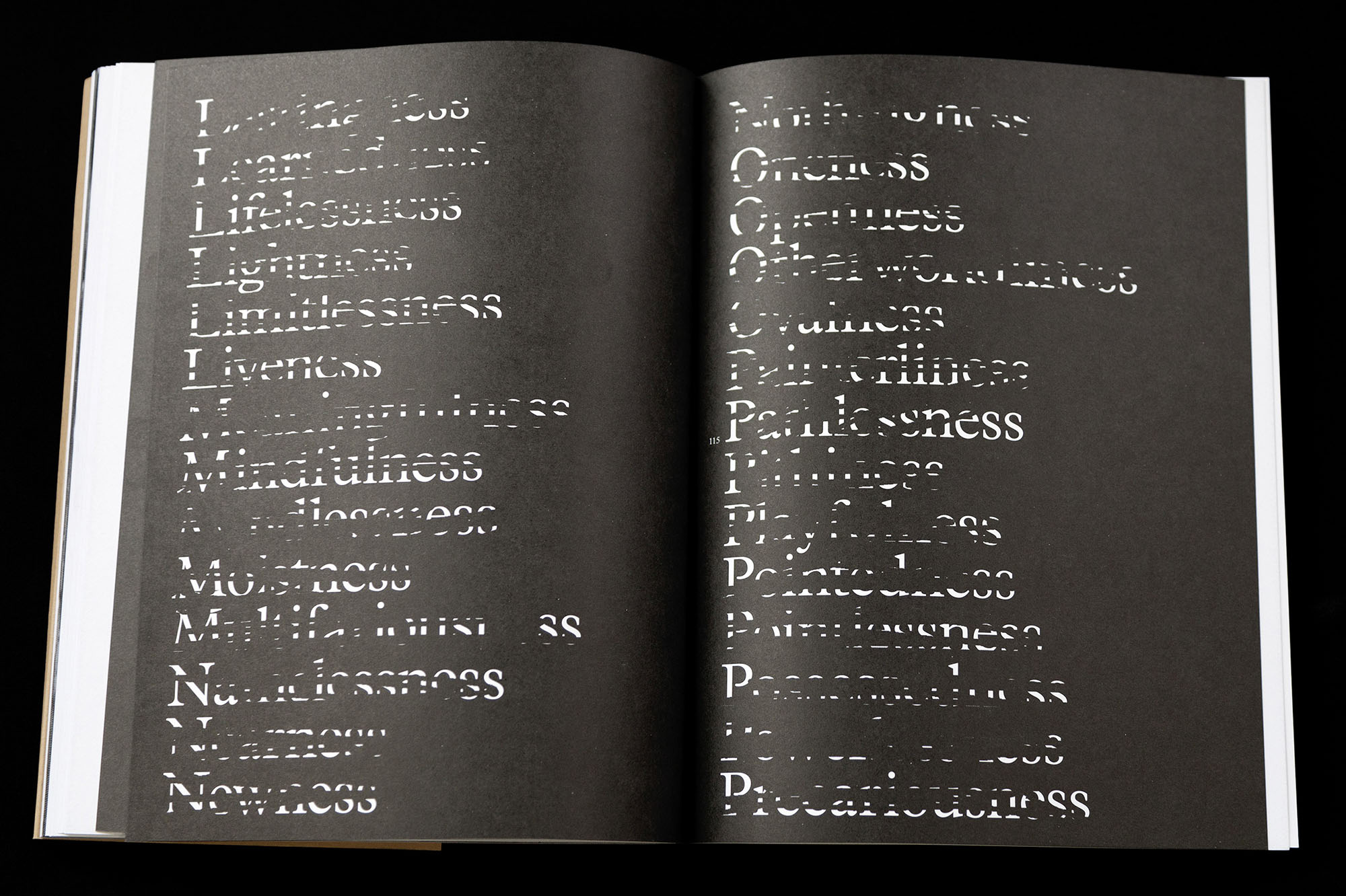

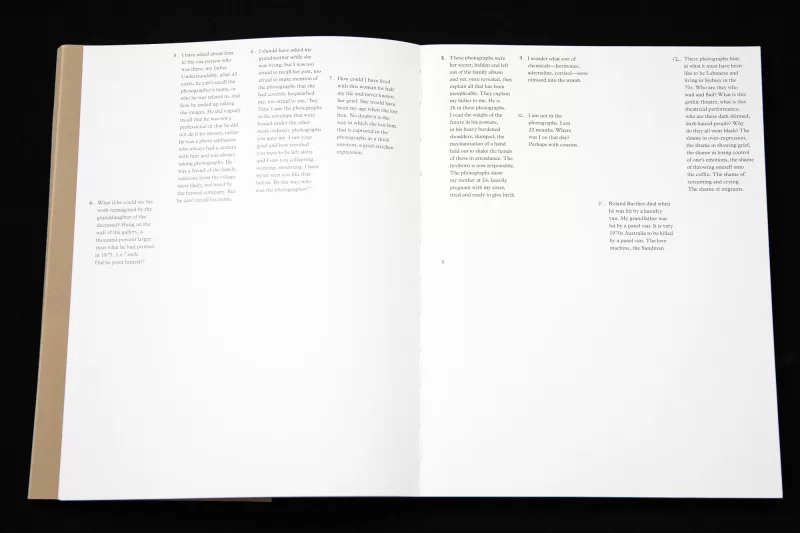

Apókryphos plays with the idea of what is present and what remains absent; “There is never a full explanation or description, only clues”, says Fahd. Using both image and text, with annotations and footnotes displayed as a ‘call and response’ between Fahd and Daniel Mudie Cunningham (Director of Programs, Carriageworks, Australia), it is a deeply moving study of the ways in which grief and mourning are visualised, experienced and witnessed.

It’s very rare to come across family photographs of a funeral, the process of mourning is generally private and not one that people want to revisit. In No.7 of your footnotes, you state, ‘How could I have lived with this woman [grandmother] for half my life and never known her grief.’ Seeing these photographs for the first time must’ve been a revelation for you; what were your initial thoughts of the prints when they were given to you?

My grandmother gave them to me indirectly; they were hidden at the bottom of a box of old family photographs. I thought I’d seen all the photographs in that box. As a child, I would often sift through it looking for pictures of my dad as a boy. When I found the envelope beneath all the familiar images, I had no idea what was in it; they took my breath away. I cried in an instant. Seeing my father as a young man grieving was very difficult. Seeing my grandmother so ‘out of it’ was also very confronting. I was both drawn to the images and horrified by them. They drew me in for what they told me of my family’s grief in 1975. They were also fascinating from the perspective of photography. Such rare images that needed to be shared publicly. But then how to do this? To ask my grandmother was impossible; I never spoke of them to her. I was so uncomfortable with asking her anything about the images largely because I knew she gave them to me in a covert fashion that signalled her need for silence.

The title, Apókryphos, comes from Greek, meaning ‘hidden, concealed, obscure’; there is a gentle paradox here as the photographs are now very much revealed and public.

Yes, indeed I am conscious of playing with the meaning, of what is present and absent. However, the reference to what is hidden permeates the project. My grandfather is hidden in the confines of the coffin. The photographer is concealed behind the camera and outside of the frame; his identity remains a mystery. The way in which the images lay hidden for 40 something years and thus the hidden nature of grief and mourning, the emotions we bury, the trauma concealed under layers and layers of obfuscation. The text in the photographs, and in the book, both tell the reader something but also obscures details. There is never a full explanation or description, only clues.

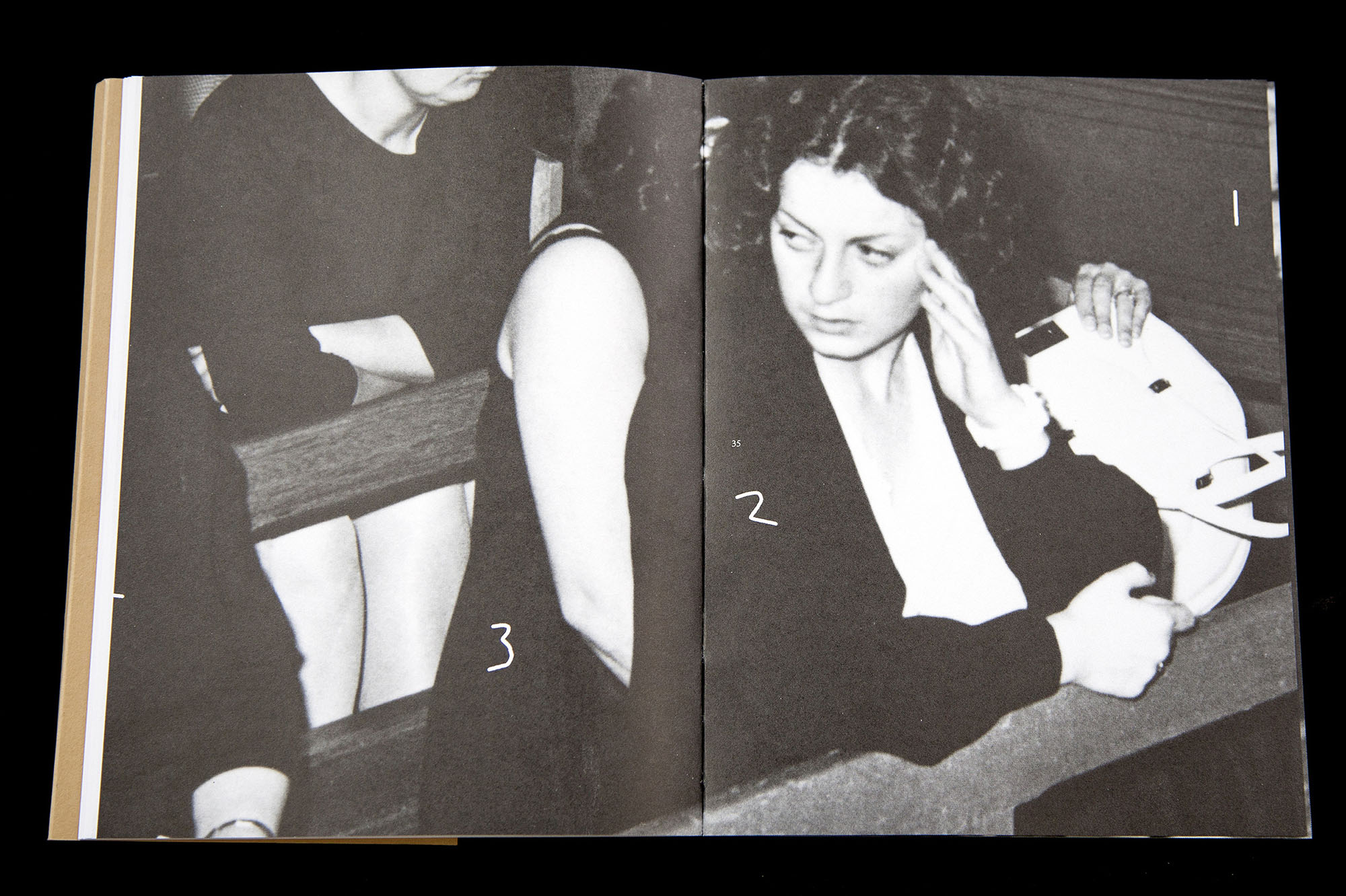

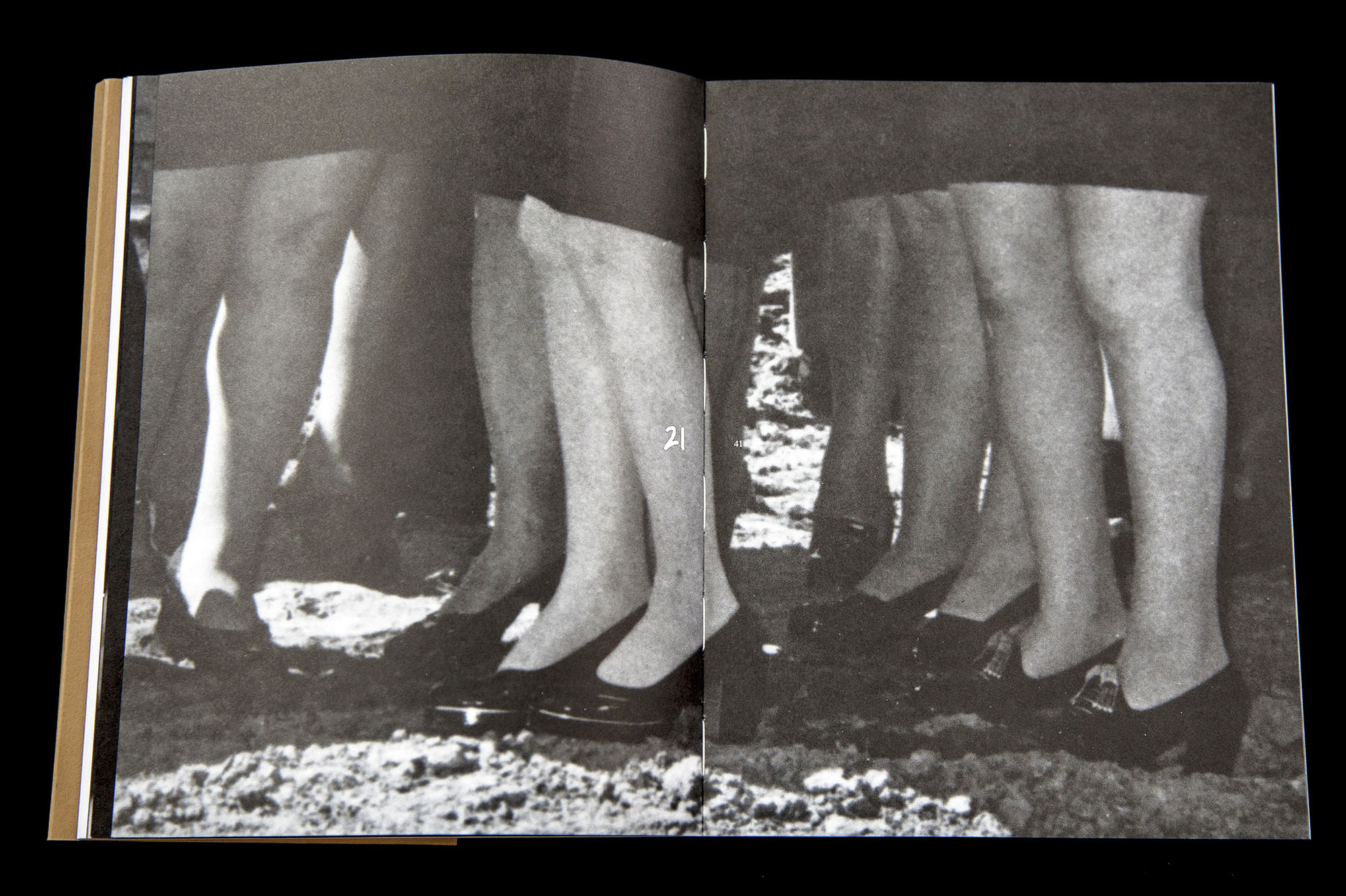

Apókryphos reproduces 24 photographs of your grandfather’s funeral and burial, with some images appearing as tight crops, revealing overlooked details in an almost cinematic manor. Could you talk about your overall editing process, and the choices behind your cropped selections?

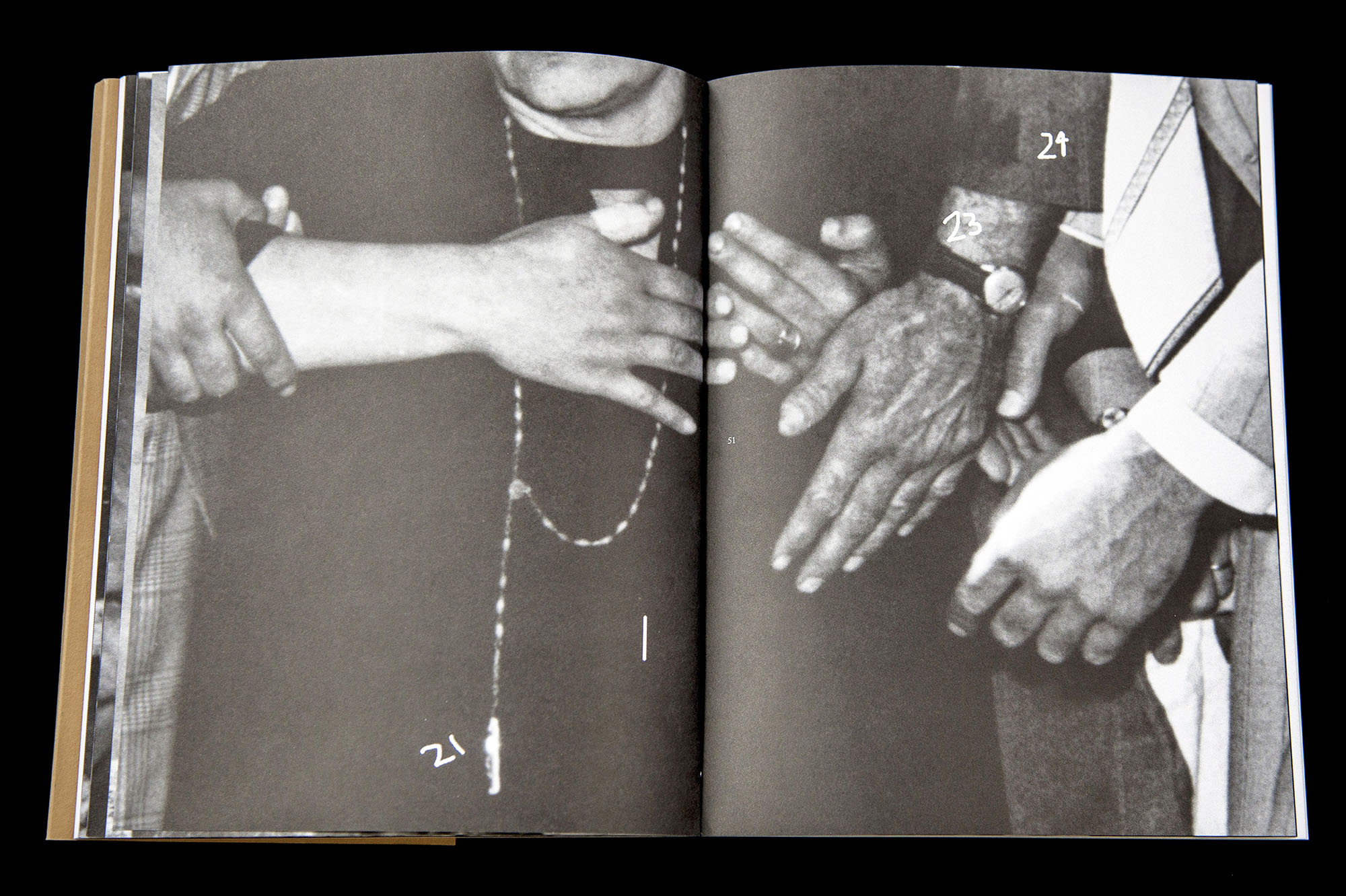

I wanted the book to be its own artwork, to be both connected to but also different from the exhibited series of images. The book as a form allowed for developing Apókryphos in different ways. The tight crops mirror my editing process when I looked at the images on the screen. I have a tendency to zoom in, to see the details of faces and hands, especially. Tightly cropping images has the effect of changing them, intensifying details, and to show something very explicitly. There is no mistake that it is this scene or that scene that I want you to see.

The reference to what is hidden permeates the project… The way in which the images lay hidden for 40 something years and thus the hidden nature of grief and mourning, the emotions we bury, the trauma concealed under layers and layers of obfuscation.

Text plays an important role within Apókryphos, with the first half of the book dedicated to footnotes and endnotes compiled by yourself and Daniel Mudie Cunningham (total of 53 each, spread over 31 pages). How did this collaboration with Daniel come about and why was it important for you to display the text in this way?

My grandfather was 53 when he was hit by a car out the front of our house on 27 October 1975. That’s the logic for 53 notes; it accounts for every year that he lived. Daniel and I have collaborated on a number of projects, he curated my first survey exhibition in 2007 and this is how we got to know each other. Aside from being a curator he is also an artist and has a close interest in death, grief and mourning, having produced extensive work on these themes.

For the book, I began by writing my piece, the 53 Footnotes. I sent this to Daniel for his feedback and we discussed what he would write. One assumes it has to be a formal curatorial essay but in fact, I decided that he should be as creative in his expression as I had been. After some further lengthy discussions, we came to the conclusion that he could write his own 53 notes, which he did in a call and response style. We both love writing and are avid readers of experimental forms of literature as well as autobiographies. We share a fascination with fragmented texts: from A Lovers Discourse by Roland Barthes, to The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson.

Text is also prevalent with annotations that sit alongside the images, as well as crude numbers scrawled across the print themselves, reminiscent of a crime scene photo. There is a forensic methodology to your approach, and I get the sense that you removed yourself emotionally as you tried to piece this part of your history together.

I actually began the work seven years after they were given to me. They had sat in their original envelope under my bed for all that time. I finally looked at them again at the end of 2017 when I wrote an essay for an academic journal, Photography & Culture. The process of scholarly enquiry, of research, requires this forensic approach. When I studied the images, I did so from multiple perspectives; Cherine the photographer, Cherine the researcher as well as Cherine the daughter and granddaughter. Writing the article was integral to the development and production of the work. When I was working on the essay, I did not know at that stage that I would create Apókryphos. The idea to use footnotes and annotation and to inscribe upon the image the numbers actually came from the essay; I wanted the images to be read as well as viewed.

Given that these photographs remained private from your family for so many years, what has been their response to the project?

I wanted to make this work for my father. I had always known about my grandfather’s death through my mother, but it was my father’s father and for all these years he had remained very silent. I wanted the project to be an opportunity to foreground the tragedy of my grandfather’s death while also using the project to catalyse difficult conversations between us; to consider grief, pain, and mourning as part of the family album, to discuss our love for each other and the pain and fear of losing each other. The exhibition and the book were a catalyst to talk to my father in detail about his past. This is what I regret not doing with my grandmother when she was alive.

All images and spreads Apókryphos, Cherine Fahd (M.33, 2019), courtesy the artist. Apókryphos is available to purchase here.

View Apókryphos in full on the Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award site.