Interview – Dafna Talmor

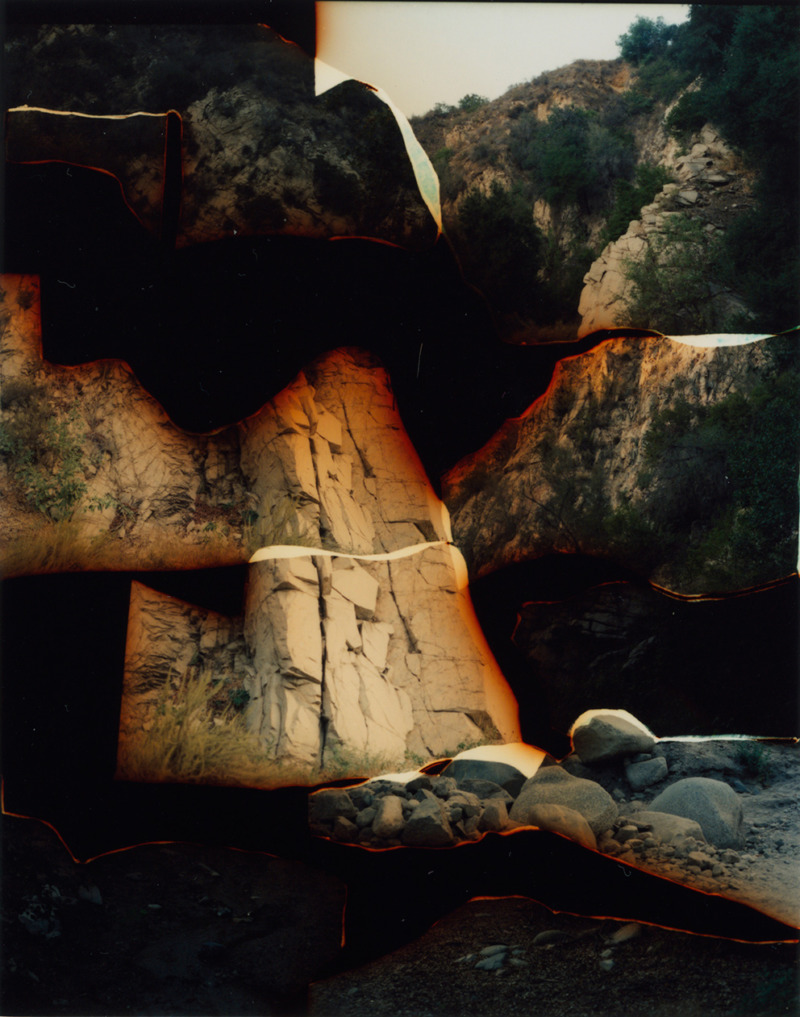

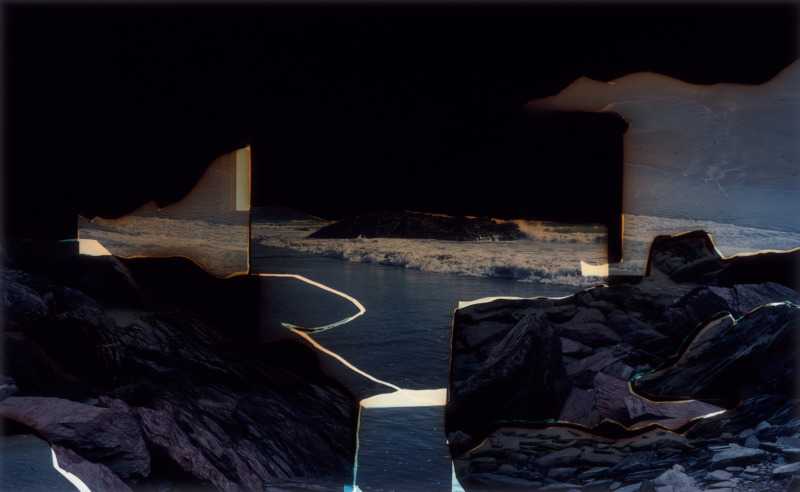

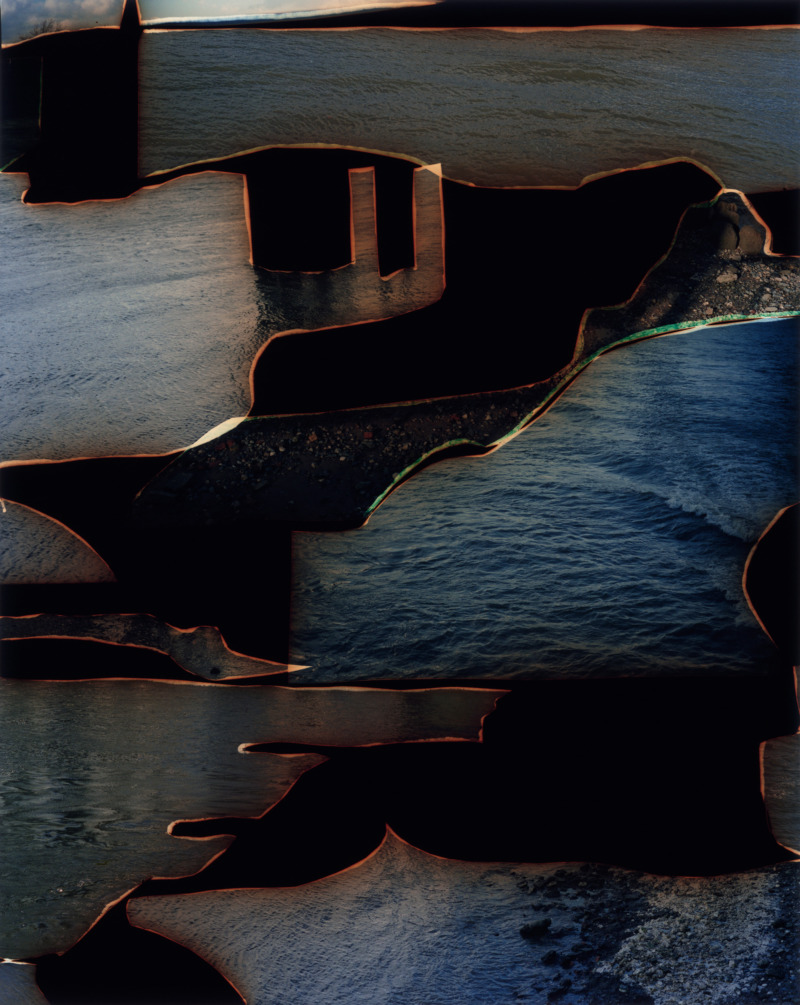

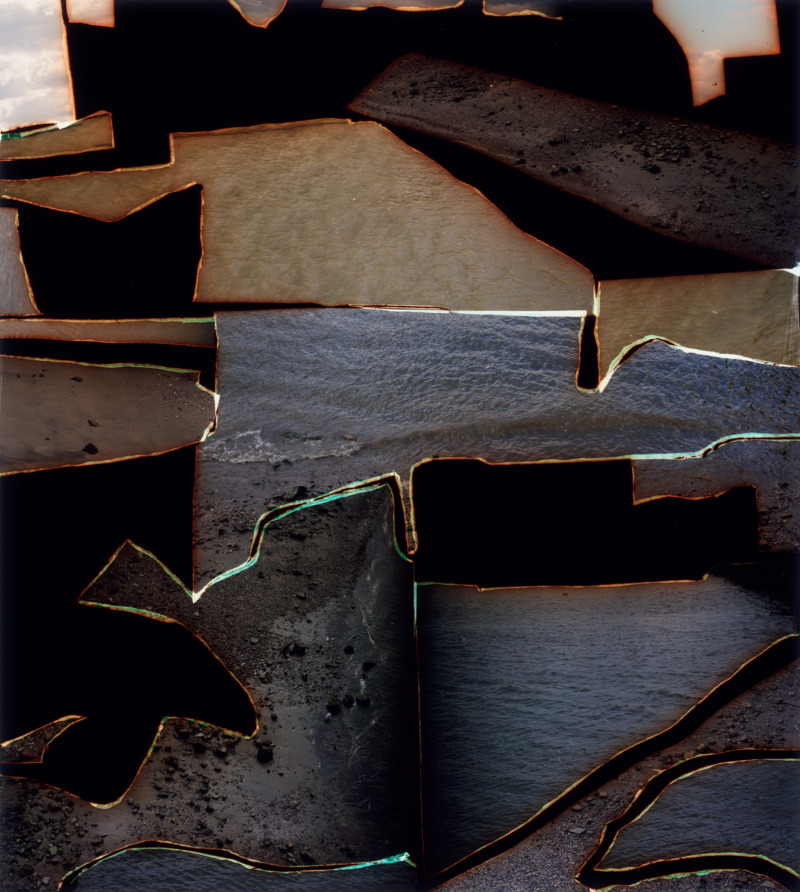

Dafna Talmor’s photographic practice has undergone a paradoxical shift. Her series Obstructed Views presents interior scenes and self-portraits with the exterior world only hinted to, yet since 2009 her practice has dissociated from reality and questioned the value of presence, depicting ostensibly natural landscapes, albeit ones with no definitive location. These, her so-called ‘constructed landscapes’, “‘real’ yet virtual and imaginary”, are the result of darkroom experimentation, of Talmor taking analogue photographs in the field and building new collaged images from multiple spliced negatives; this method, having been informed by historical debates, were initiated early in photographic history and reignited widespread in the adoption of digital processes. These images, a combination of circumstance and planning, preparation and chance, reveal the editorial eye that all landscapes are subjected to.

Talmor’s constructed landscapes have been exhibited in Her Ground: Women Photographing Landscape (2019) at Flowers East, Unseen Amsterdam 2018, and Photofusion 2017 amongst other shows. Most recently, she exhibited a selection of new works in Straight Lines are a Human Invention at Sid Motion Gallery, London. Following the opening of this show, I joined Talmor at the gallery to continue an ongoing conversation on her practice.

Do you think by cutting up the landscapes and introducing more to them, are you meaning to bring more together by the introduction of further parts?

I think a bit of both. The thing that tends to be cut out initially is anything that is very obviously man-made, things like roads, structures, bridges; anything that is somehow interrupting the so-called ‘purity’ of the landscape. The reason I say ‘obviously’ man-made is that it’s done with the awareness that a lot of elements that seem natural are very much man-made as well.

The other thing I want to point out is that even though at first I removed what I felt were interruptions in the landscape, very quickly I realised I was creating my own man-made interruptions through the negative space that was left behind. It points to the manual process rather than something mechanical, which usually relates to the photographic process.

Where did this idea of cutting out the ‘obviously’ man-made come from?

I think it came about because I really wanted to have some kind of standards to work within. I didn’t want the collage to be arbitrary, I wanted a specific reason behind my cutting these negatives. The other reason was, I felt anyway, as soon as you have a road or a path or anything recognisably man-made, you start to create a narrative, and that was something I was hoping to resist on some level.

I hope that these become more spaces rather than places. I feel that when you remove those elements its easier to get lost and inhabit that space psychologically. I think about your relation to them physically, but it’s quite obvious that you can’t inhabit that place. This defying of specificity is something I’ve always been interested in; it’s something quite utopian. It could be anywhere, or it could somehow be more universal than if you were to have a very recognisable history, time or place.

So is there any significance in the original places that these photographs were taken?

The project originally stemmed from images that I shot at locations of personal significance. On the one hand, I’m trying to strip those places or locations of their associations, but I’m aware that because it’s photography and it’s so indexical that it’s impossible to do it all the way. But there’s an aspiration, and that’s why there’s something utopian for me; the aspiration, the process, the work itself.

That’s how it links back to the titles and the codes I come up with, which are linked to the dates the original pictures were taken, and in some cases the abbreviation of the location. So again that’s pointing to the fact that I don’t want you to know where they are exactly, but at the same time, it’s important to feel them anchored to some degree to that original location and to the Real. But then it’s very much an imaginary space, you know, that could never exist.

I hope that these become more spaces rather than places. I feel that when you remove those elements its easier to get lost and inhabit that space psychologically.

Speaking of the imaginary space, what do you think of the blanks in the photographs? Because they’re so prominent but considered secondary.

That’s if you think they’re blank. I think they function in different ways. What I mentioned earlier was that the negative space points to what was there before. Hopefully, it raises some questions or activates the imagination in trying to figure out what those voids are. I hope they start to be read as elements of landscape within themselves, even though you know it’s a blank space.

It can also be read as a commentary on photography. If you understand photography then you might be aware that nothing’s there, but if you don’t, you might read it more as a form. The void then defines what is around it through its absence, so you begin to think more about its edges.

Yes, because the edges play such an important part in the images.

Yes, and the outlines are manifested in different ways, depending on the felt tip marker that I used to outline the edges and the thickness of the line; something that is very hard to control, and then how precise I am or not about how I cut, it brings in these colours; sometimes it comes out more turquoise, sometimes more green, other times more orangey. All of those are things I don’t really have control of, so it brings in an element of chance.

For the most part, what I see is a great degree of control over what you do, but then there are these very small moments of chance.

I think it’s very much a combination of those two aspects. I shoot quite quickly, I’m not too precious about how I frame, because I know ultimately that I have control once I go into the studio in terms of reconfiguring and reusing those frames. There are also all those things where I don’t know how they will come out. I know to a certain extent that when I use the pen, the pen will create some kind of outline, but I can’t control everything. Because I’m working on such a small scale, before they get scaled up, then the way that these lines and marks manifest, is completely out of my control. Sometimes I slip, sometimes there’s mistakes, hesitations, there’s the tape that leaks into the frame. All of those things, those imperfections, are things that I really embrace, and start to become an intrinsic part of the visual language that is created.

There’s a link right back to the invention of photography and the story of Henry Fox Talbot wanting to exert more control over his pencil and view of the landscape. Also, the early debates about skill versus chance, before the mathematical relationship of the exposure triangle was proven.

I tend to reference the combination prints of the Pictorialists Gustave Le Gray and Oscar Gustave Rejlander as being key to this idea of constructing a landscape and dealing with the constraints or the limitations of technology in rendering idealised images of landscapes. They were led to shooting the sky and the sea separately and bringing those two together in the darkroom to construct an image that was truer in one sense. For them, it was about disguising that manipulation and construction and making it as believable as possible, whereas for me it was all about exposing that construction.

You say disguising, but I was recently reading Miles Orvell’s 1989 book The Real Thing where he states that because the construction of these images was widely discussed amongst photography groups, they’re hiding the effects visually…

They’re hiding the effects visually, but they’re proud of their skills in producing that image. That’s what I’m really interested in, in relation to the accusations of photography as science versus photography as an art. I think most of the Pictorialists had begun as painters so they took on, or mimicked the act of painting, and applied it to their photography, constructing an image from different elements in different ways. That’s something that’s been done since its inception.

Sometimes I slip, sometimes there’s mistakes, hesitations, there’s the tape that leaks into the frame. All of those things, those imperfections, are things that I really embrace.

One of the things is the idea that these are photographs of landscapes, but they’re not; if you want to be pedantic they’re photographs of pieces of plastic. It’s interesting how many viewers focus on its perceived subject.

I’m interested in how, as much as people know when they look at them that they’re constructed and made of plastic, the viewer projects this faith in the fact that I’m trying to make sense, and on some level, they believe that this place could exist. I was doing a talk once and someone introduced me to the term ‘visual desperation’, which is a psychological term for our search for meaning. I feel like it’s so hard to get away from that. I’m not talking about something that is universal; I don’t believe things can be completely universal. I think generally speaking when people look at them they are trying somehow to piece them together.

I had a group of students from Camberwell who came and asked, “do you think that these are somehow truer than a straight image of a landscape?” In response, what they convey for me is more my experience of viewing a landscape which is this scanning of multiple views which I conflate, rather than having a fixed position; this singular view which is meant to be an idealised view.

Do you think they need to be true though, rather than more true or less true?

No, I don’t think so. I think on some level they need to be relatable, and that’s why for me there’s this balance between the disorientation that I hope they introduce as well as the elements that anchor the viewer, are relatable and are enough to be able to fill those gaps; enough to make people more aware of their position when they look at a landscape or an image.

What it hopefully does is show that there are multiple truths, whether you look at a straight landscape or one that is so obviously constructed, and I think that’s an impossible thing to get away from when you’re talking about photography.

There’s this obsession with a hierarchical relationship to this experience which is a pure experience of being somewhere physically. That’s exactly what got me started with this project. I was very aware of my experience of seeing the landscape and how impossible it was for me to capture it, or photograph what I felt through one frame or a set of single frames. This is, in that sense, more true to my experience of what I see.