Daniel C. Blight – The Image of Whiteness

But, at the same time, whiteness remains for most people as an incredibly specific and strange and new thing to think about, at least in the photography community.

The author, lecturer, and photography critic, Daniel C. Blight was recently in New York City to discuss his latest editorial collaboration The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization as part of Printed Matter’s Art Book Fair. Blight uses a combination of discourse analysis, photo exhibition, and interviews with leading intellectuals and academics to draw attention to how whiteness, as a racial construct and category, informs photographic practice and the writing about photographs.

Blight’s desire is that people, especially those who self-identify as white, will turn what they read about the legacy of whiteness and photography into meaningful personal, pedagogic and political action. Writer and visual historian Drew Thompson had the opportunity to interview Blight about his book and its most recent success in contemporary art and academic circles.

What was that moment in time when you felt like you had to write about photography and whiteness?

When it came to the publication, I was asked to do something in relation to photography, because that is my academic specialism. The thing that struck me was that there is very little literature on the relationship between photography and whiteness. There is some on contemporary art and whiteness, and visual culture and whiteness but it almost exclusively exists in an academic, peer-review context. The publisher – in this case, the two publishers that collaborated [SPBH Editions and Art on the Underground] – don’t usually produce academic, scholarly books. But they were happy to include that form of research in a more public-facing publication. So, there was a necessity for me to specialize. The book could not take on a huge subject area from an editorial point of view because that would end up overly loose as a book. But, at the same time, whiteness remains for most people an incredibly specific, strange and new thing to think about, at least in the photography community, despite it being a widespread power structure.

In your own words, how would you characterize your role in this project?

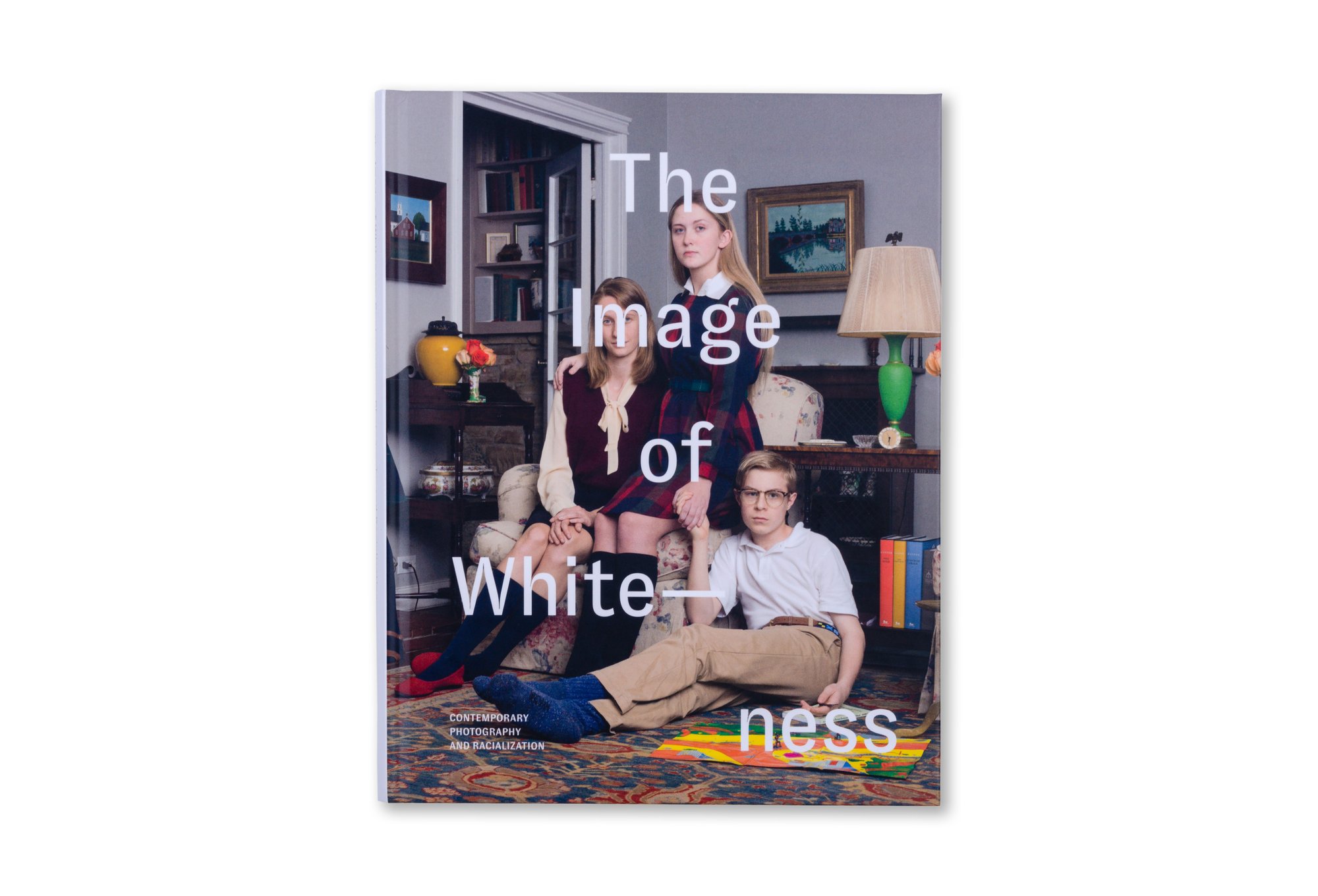

I guess the simple answer is that my role editorial. But I also like to think of it as fundamentally collaborative. There were various things about the publication that we wanted to avoid, such as the positioning of my name for example. You typically see the editor’s name on the front cover. That’s something I wanted to avoid. You typically have a typographical hierarchy between contributors and editors. The editor would often supersede the contributors. Again, that’s reversed. These are small things, but I think important because there has to be a politics to my own relationship with the subject. I am white, and this book is about whiteness taking a back seat, dying a certain kind of symbolic death.

So, what kind of book is The Image of Whiteness?

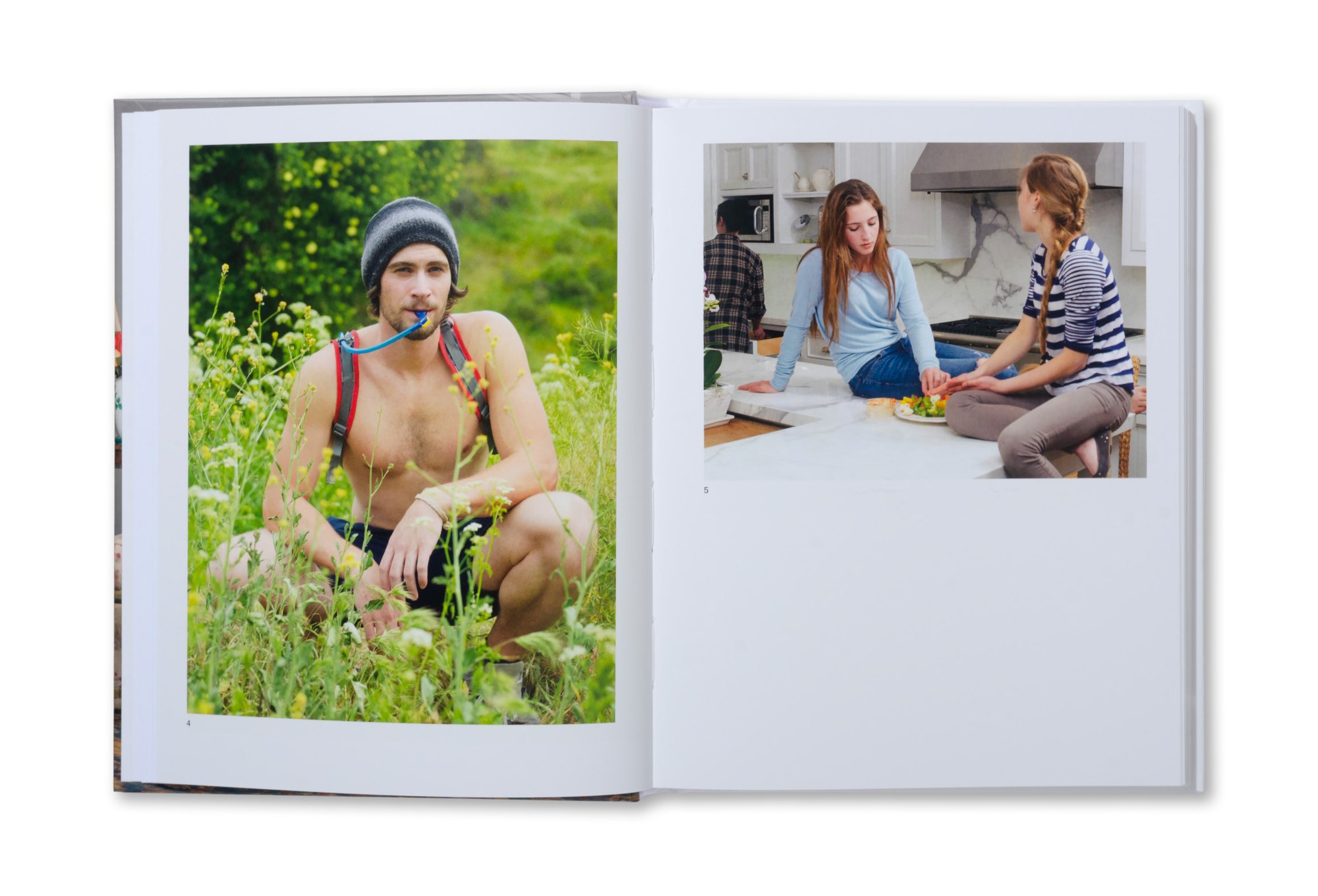

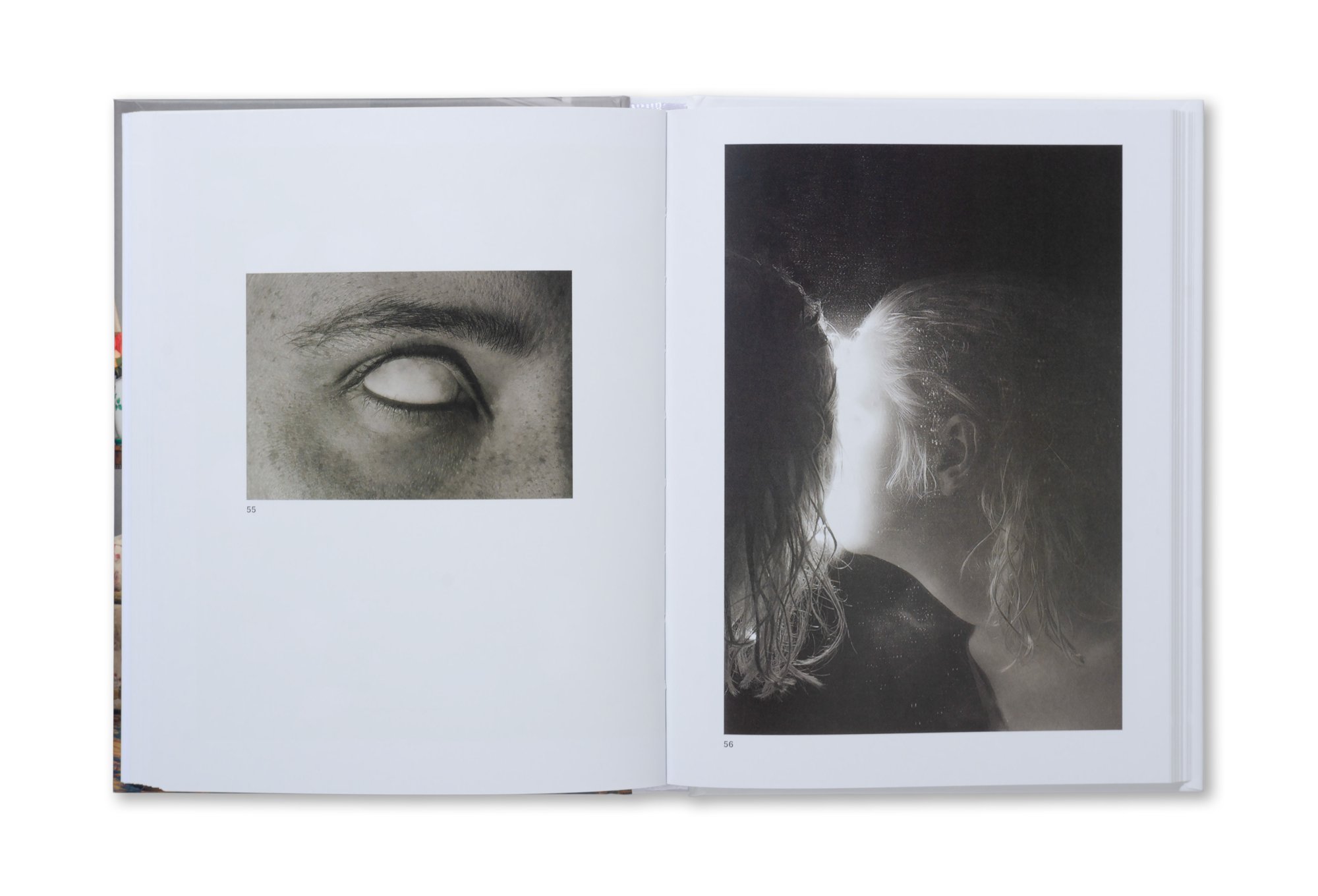

I think it is a photo book because the bulk of it is a sequence of images that offer a particular narrative with respect to whiteness as an image, and form of imagination, as I describe it. It’s a critique in that it takes a critical position, but I also want to be clear that none of the philosophical ideas pertaining to whiteness are original. I am on fairly well-trodden ground as you can see by the footnotes. However, I think the book renders key ideas from critical whiteness studies accessible, and I would like to think that there may be some original thinking happening on my part with respect to photography, but that’s for other people to decide.

What is interesting about this project is how subtly you show how critical race studies is reliant on photographic images and language. In thinking about the language of photography, how does one select a photograph to tell that story?

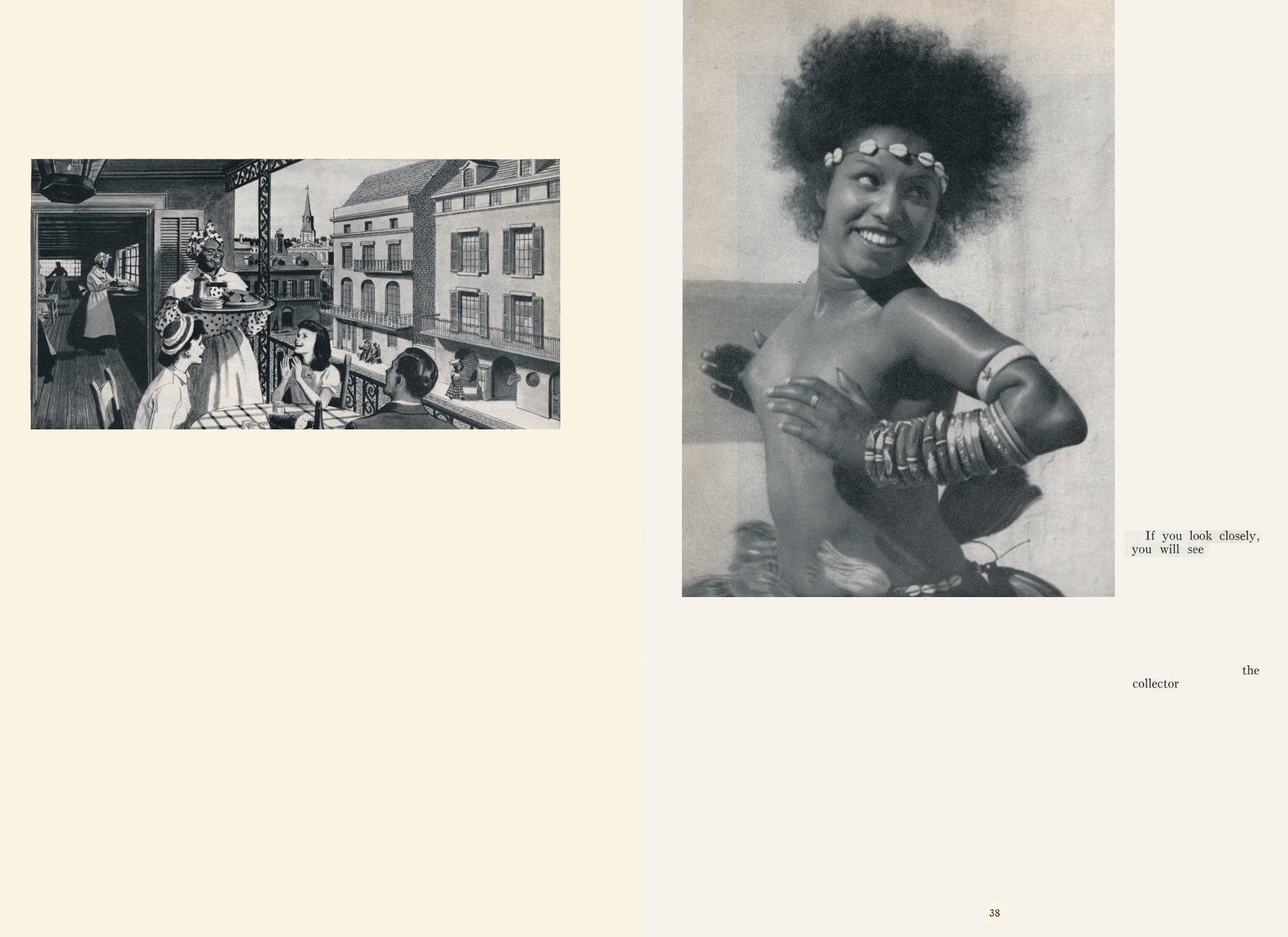

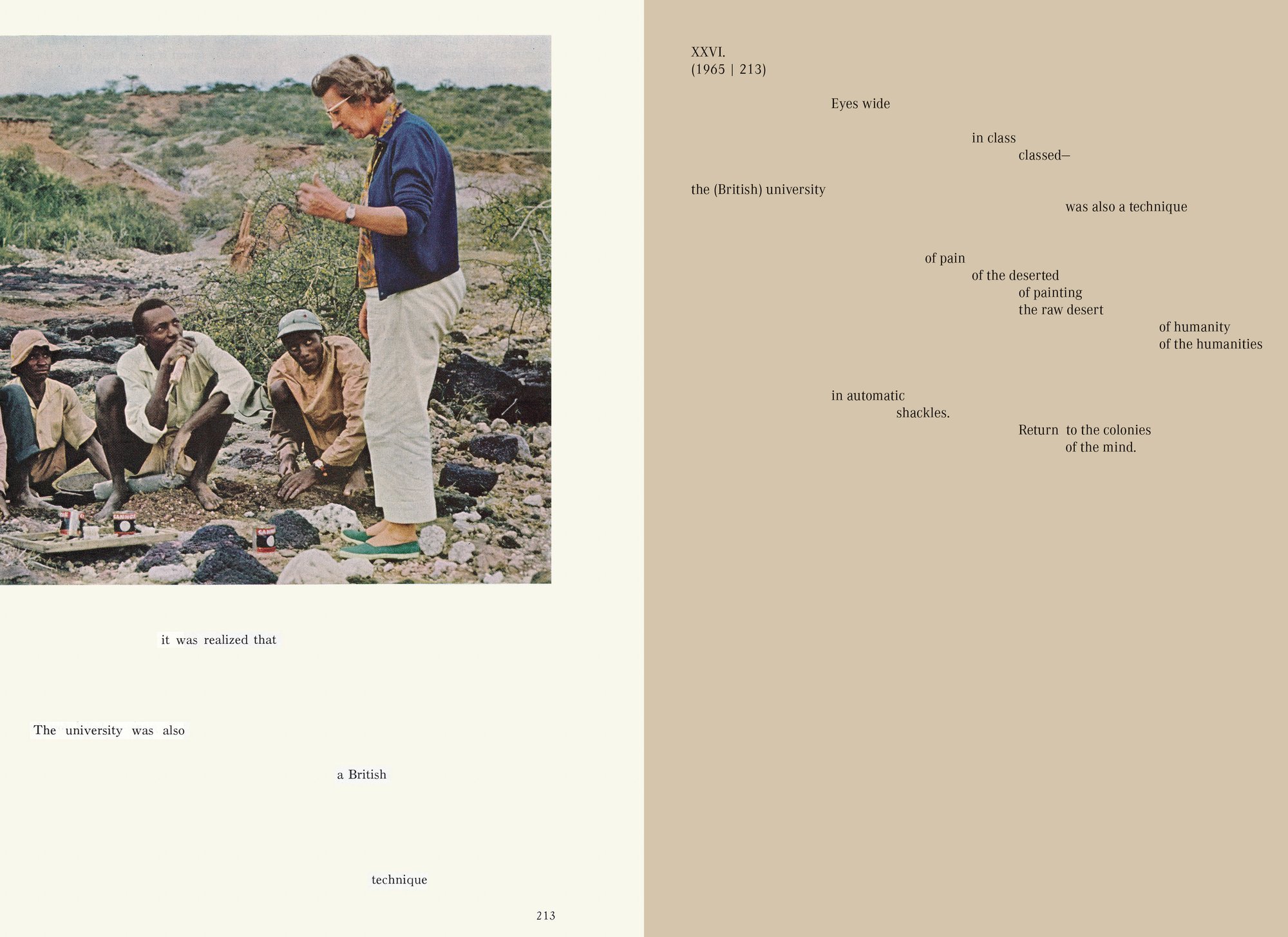

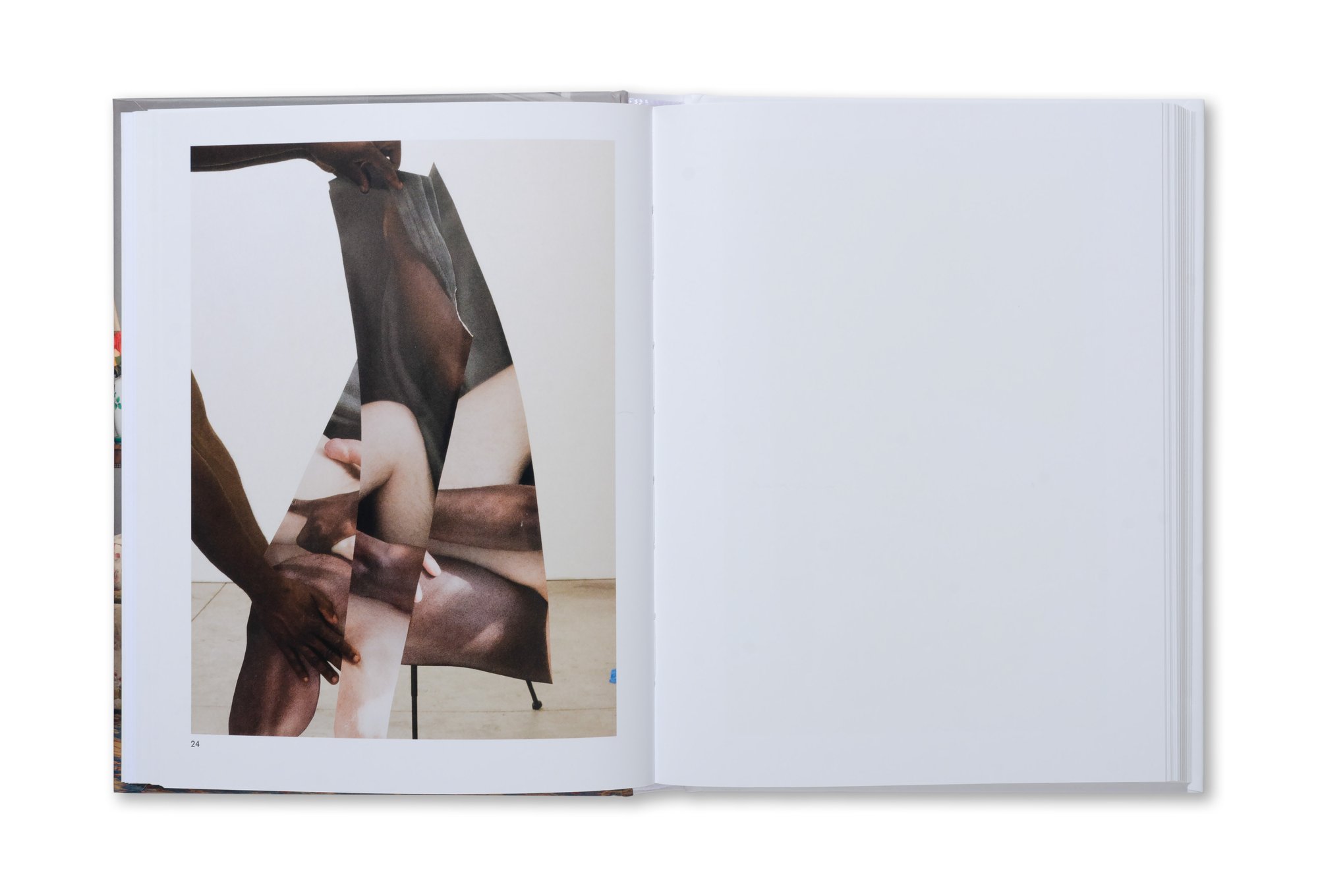

There is a literal tension in the Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê works of book spreads from the monograph White Gaze. This work here [Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê] was amongst the first photographic works about whiteness I encountered. I had seen Hank Willis Thomas’ work before, A century of white women, and a couple of other projects. When I discovered this book by Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê, is when I really started thinking about bringing together a lot of this material. I wondered if there was any more out there. I guess it’s interesting what you say about the almost accidental use of modes of thinking in critical studies of whiteness that you also find in photography theory…

Everything is printed on white paper, in varying gradations. Can you talk about those creative choices?

The idea to use three different types of white paper stock was a design choice made by Brian Paul Lamotte, the book’s designer. The logic offered, which I think is appropriate, is that it speaks metaphorically to subtlety in the different gradations of whiteness. There is also a practical necessity in terms of the thickness of the book, the weight and cost of the paper. One wants a thicker coat of paper for reproducing images. Then it seems unnecessary to continue such a luxurious stock when just printing an essay. The size of the book is very important. It’s a photobook, and to some extent I suppose, a critical art book.

These are small things, but I think important because there has to be a politics to my own relationship with the subject. I am white, and this book is about whiteness taking a back seat, dying a certain kind of symbolic death.

How does one select images on this topic, when in effect many of these images are products of an ingrained system?

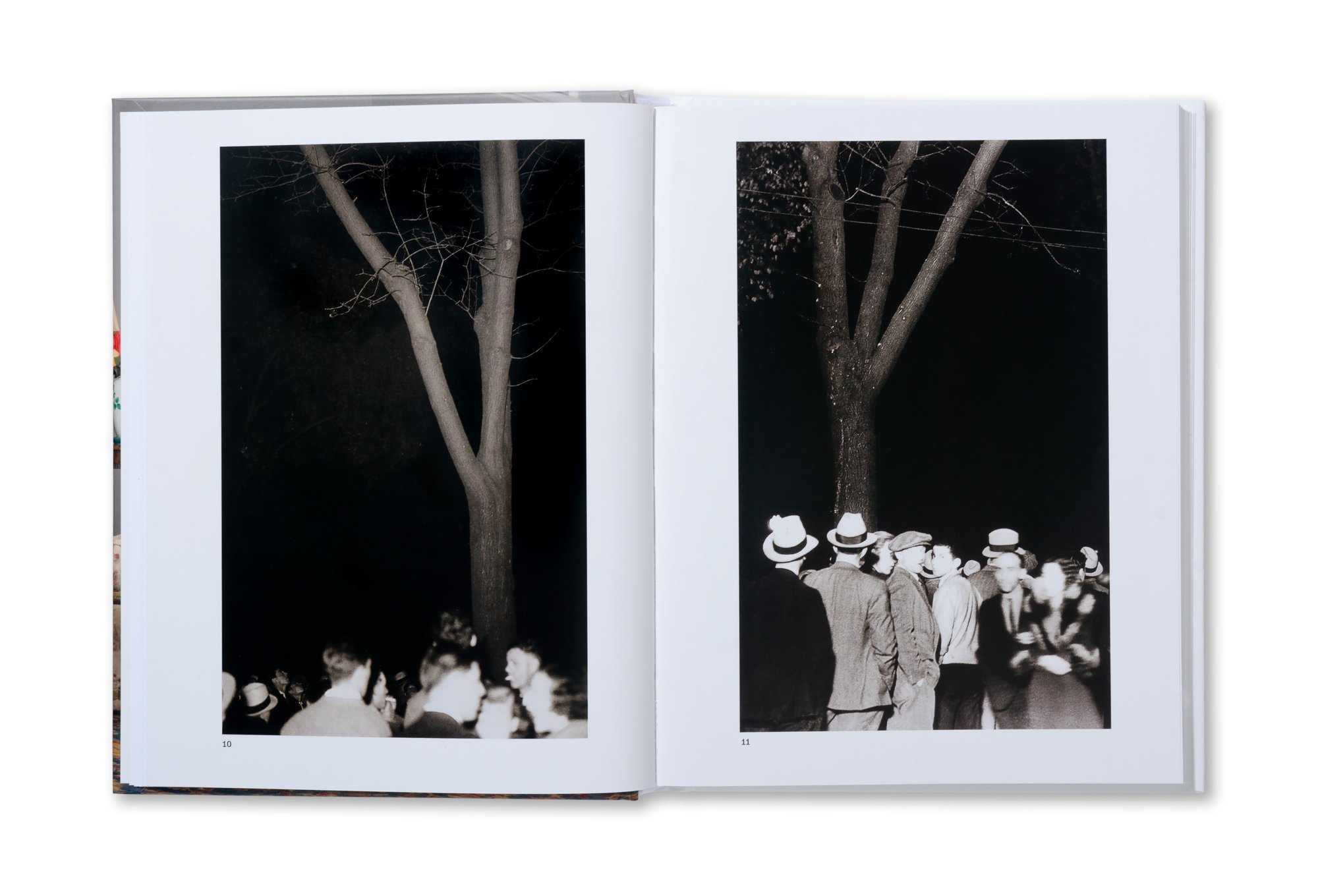

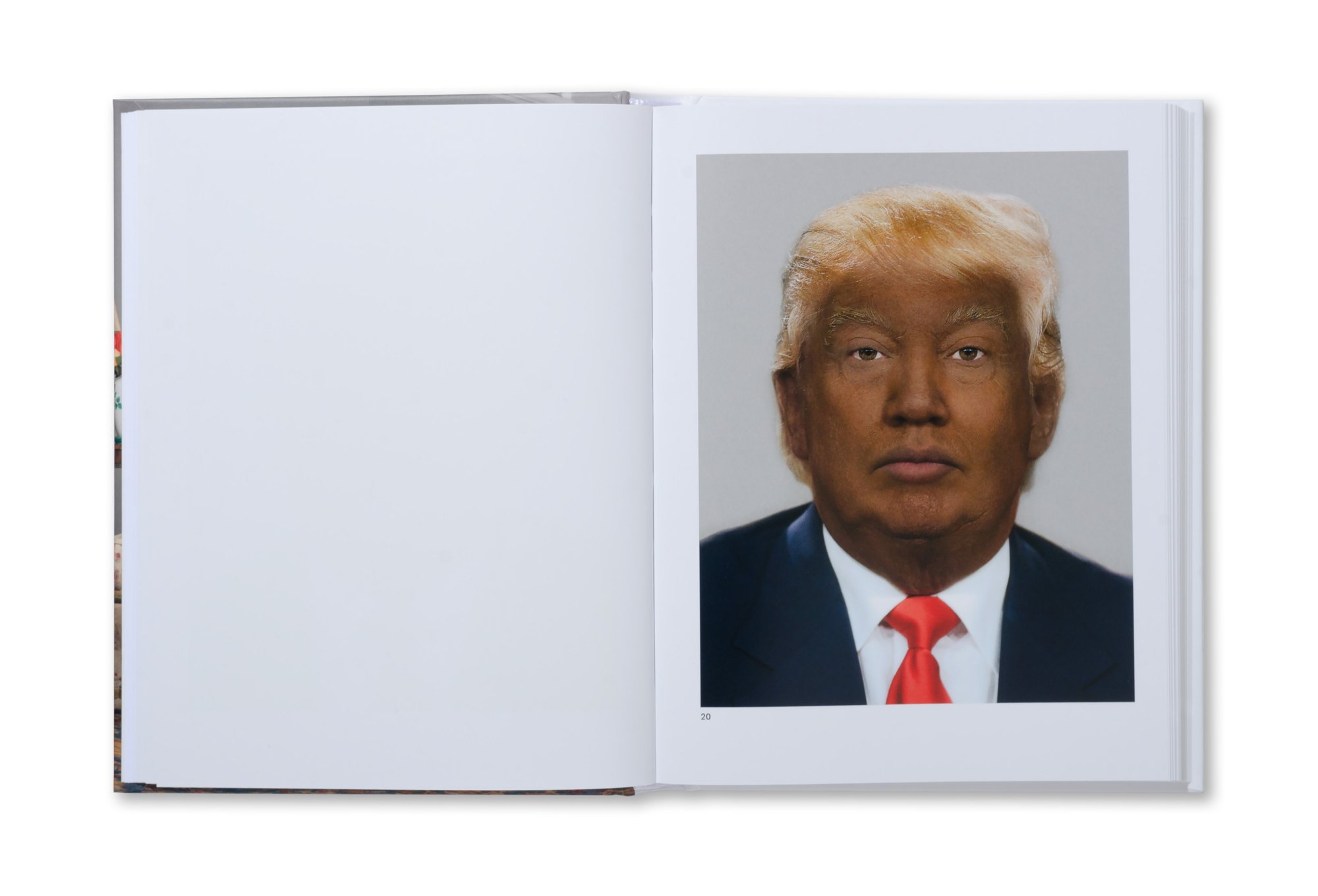

I think the idea of whether it is possible to directly photograph whiteness is interesting, and that is something that Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa brought up in the interview. For me, that is really crucial. Whiteness, in a specious sense, asks to be ignored, and so, it creates both a psychical and visual life for itself that seems to be indirect when you approach it, scurrying away when you try to reach out and grab it.

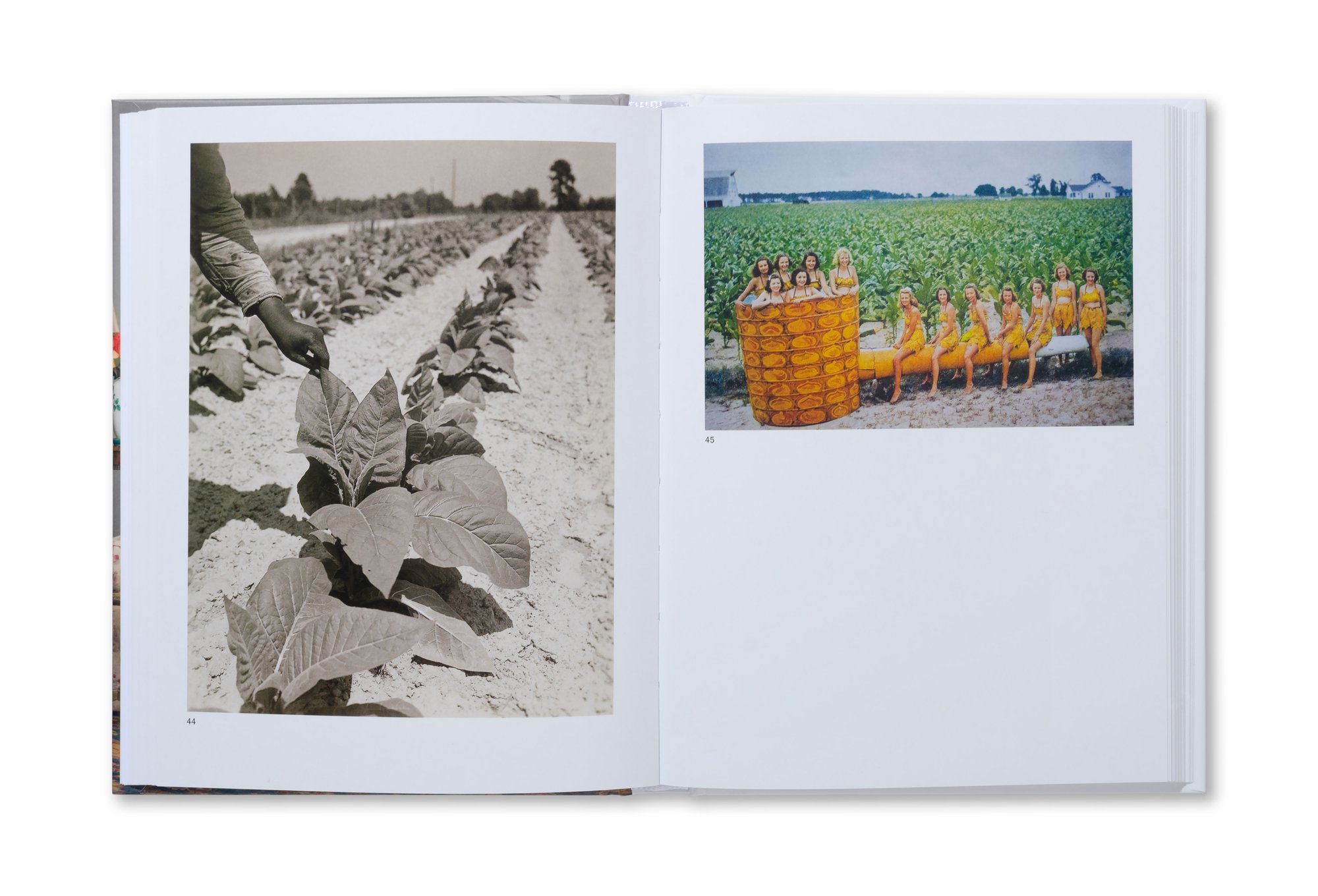

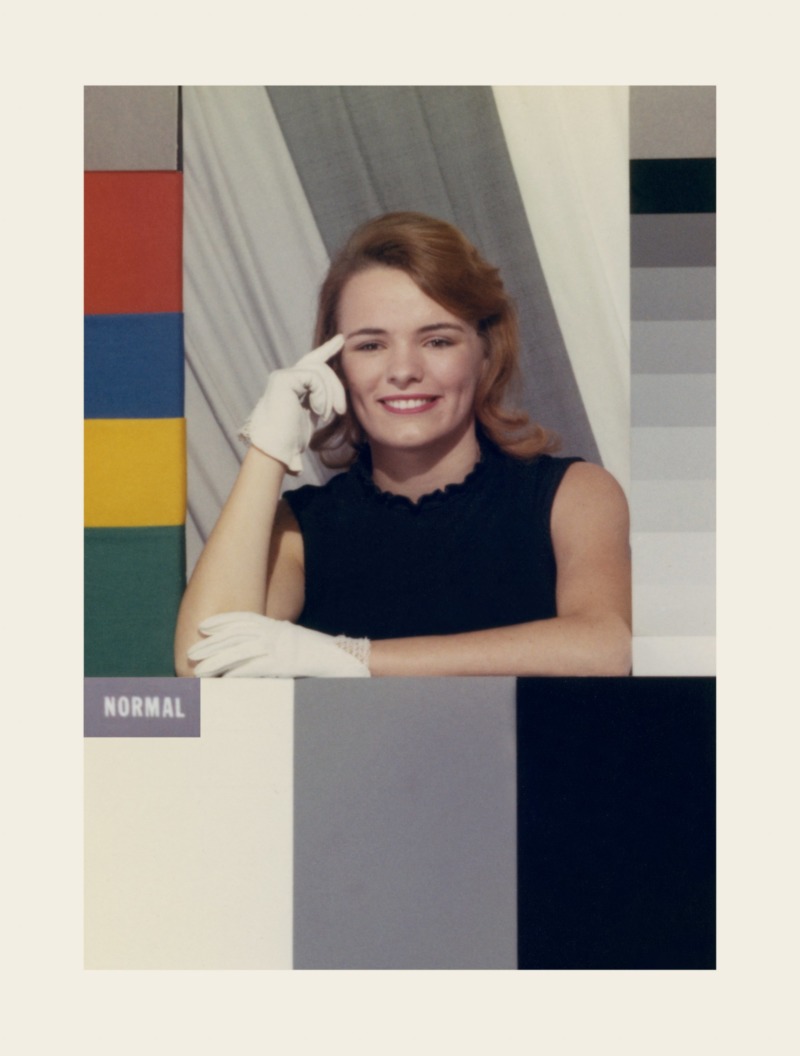

When I researched different artists that were engaging whiteness or race in a way that I could interpret through the conceptual framework of the book, it just so happened that lots of this work were appropriation art that lifted images from archives. On the one hand, that is kind of obvious, because it’s [the book] with history. On the other hand, there is this weird depth to historical images, especially National Geographic, Michelle Dizon & Việt Lê, Hank Willis Thomas’s images come from various advertising contexts, Broomberg & Chanarin take from the original Shirley cards. There is a sense that racist historical images need to be reclaimed and given new meaning.

What would you imagine the history of photography to look like if we attend to this idea of whiteness? What do you want the history of photography to look like after this book?

I want to put the history of photography as we know it in its deathbed, effectively. It is an incredibly European eccentric discourse in terms of key texts and publications, and an incredibly white, male world when you look at the institutions that hold power and command the biggest exhibition programs. There is definitely a sense that I am committed to doing everything I can to antagonize that institutional stability and to create spaces for artists and writers, which are largely confined to academic spaces and don’t see the public life that is associated with big photography shows. My point of view has to be fairly precise and pedagogical and that has to do with reading lists in the classroom and trying to create a space for students to think about how they can change what institutional photography looks like through forms of practice and forms of declaring a lack of interest in what institutions are currently offering.

All images and spreads courtesy Self Publish Be Happy