Interview: Elizabeth Bick

A performance is, say, the search of a life without memory where the present, the moment gains significance. In a life, without a past and a future, every mo(ve)ment would be considered as a performance piece, every space would become a (frozen) stage. A new perception of time occurs. Actually, life is a performance, a stage in itself where our bodies utter certain words, even though we choose not to speak.

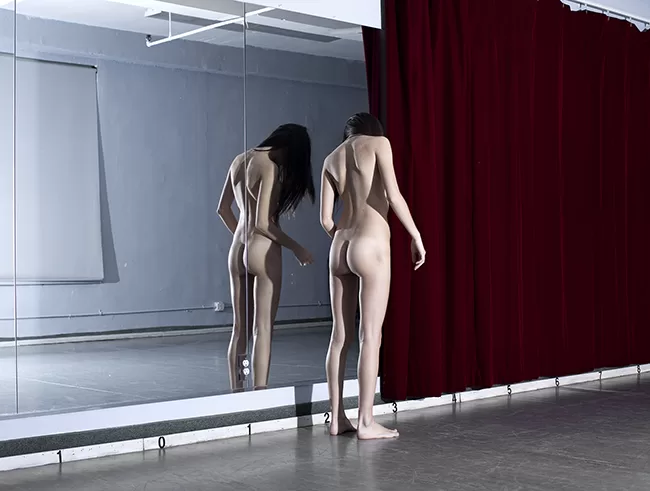

Essayist and dramaturge Andre Lepecki defines choreography as the writing of a movement; a reading-dancing (Lepecki, A.(2006). Exhausting Dance: Performance and the politics of movement. NY: Routledge, p. 27). A similar approach is seen in Elizabeth Bick’s photos: the artist (re)writes a choreography through another medium. There is a performativity, a narration – hidden. What we see is a certain scene that pretends to be simple – people walking on pedestrian roads, a woman with closed eyes, another one concentrating on her reflection in the mirror – however there is a production, a story generated before the instant that photo is taken. Bick creates stages where everyday movements or untrained dancers are valued – reminiscent of dance/performance pieces of Judson Dance Theater.

Bataille mentions the impossibility of the word ‘silent’; the moment one says ‘Silent’, there is no silence at all – the word itself is contradictory. Bick’s figures are evocative of this contradiction. Photographed objects seem silent, nevertheless the body is in action. Through this concentration, directed towards the figure’s silent movement, the same body acquires a voice, becomes audible. The composition, the rhythm in the image creates sounds as if we are about to hear the breath, a cry; thoughts even. The figures are introverted − in the state of listening the moment, lending an ear to their own bodies. Intriguingly, that inner sonority also develops an absurdity, an uncanny nature. We witness a moment of a revelation that is staged by the photographer.

How does 14 years of dance education influence your photos in terms of your approach to the body – as a body who serves for a spectator or as a moving body in space? When you were dancing, your body was the attraction point. Nevertheless now, there is a shift.

Dance is something that I can’t seem to escape in my pictures. As a dancer-cum-photographer, I’m obsessed with representing female movement, as similar to, but distinct from, the representation of the female body. Before photography I had a past-life of ballet rehearsals and a Catholic women’s education. My body existed to endure physical strains in the service of aesthetic perfection and seamless collective movement with my fellow dancers. I, with my fellow schoolmates, was a vessel to embody divinity. I was always in one uniform or another. When I discovered street photography, with dance and Catholic school a thing of the past, I set my own stage, in the real world, perfecting scrutiny and harmony of movement. Josef Kudelka, Diane Arbus, and Bernice Abbott all created other worlds, and I sought to create mine as well. I wanted to intervene on what was happening in the street to craft my own sanctified dance. Also, it must be said that photography is tedious: there is stricture of technique, a rectangular barricade, which feels familiar.

Apparently in all your photos a performance is taking place; every photo is a stage. Whilst creating the stages in your photography, is everything fixed in your mind or do you allow encounters, sudden unexpected changes?

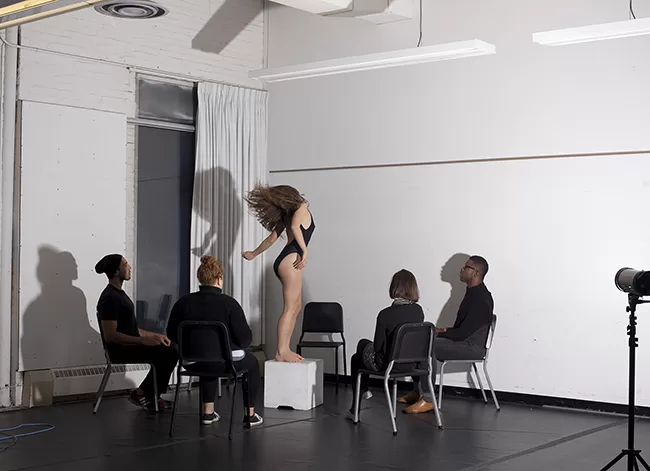

The perfect harmony of control and chance is the key to transformative pictures for me. Seeking out non-descript spaces, working in theatrical daylight, and hiring dancers to mimic the gestures of passers-by is a method I used. An improvisational dance is formed for the camera. I also held casting calls for women who fit my own physical description. I asked them to dance for the camera in their audition. We were performing for one another in these private spaces.

I use the street to find most of my subjects. I often decide what I am looking for on a particular day and search, and wait until I find it. It becomes a game, or a test of fate, a test of wills. And, sometimes, it works. Ultimately, all bodies in this work are considered performers, including me. This way, the subjects exist symbolically, not literally.

What happens before and after the instant that you create a stage?

Setting a stage and then relinquishing control forces fate and entropy to take over. The stages can’t be static, they are public streets to everyone else. I have to credit chance, fate, destiny, whatever you may call it, as a collaborative partner, and myself as a vessel that accepts and uses improvisation of everyday life. The hard part of patiently waiting, then capturing before the moment or person literally passes me by.

Sadly, because of Hurricane Katrina you had to move to NY and deal with a new challenge. Do you feel that it changed your approach to your work and if so, how?

In 2003 I began photographing the Voodoo community in New Orleans, until Katrina decimated most of the temples. The grainy, dark and moody pictures were also observing movement: a series of dances that invited the spirit world to incarnate bodies of members of the congregations. I was trying to photographically represent the invisible ‘spirit’ within a medium that requires something tangible.

New Orleans is earthy, sultry, mysterious. The shock of New York’s urban jungle did change my work, maybe the work became more brutal, less soft. But also I became much more ambitious, thinking of representing my own search for meaning, instead of by proxy of a religious congregation. The fabric of strangers in the street was where I began. The work in both places looks different, but the obsession remains the same.

Where did the idea for the series Casting Calls (2012) come from?

As a ‘people’ photographer, there is an inevitable internal conflict that occurs when placing individuals in front of my camera and representing them photographically. But, on the other hand, I am eternally pulled to study several aspects of humanity through the pictures. It’s a negotiation process. I conducted casting calls after a conversation I had with a theatre director. Actors and dancers are trained to use their bodies, voices, and movements to convey the vision of another. They invite the chance to become a type of raw material. I do not ever capture the essence of individuals in my work. With actors and dancers, I feel there is this understanding between us.

I also think it’s important to say I hired most of the subjects at an industry-standard rate. It’s key that the work surrounds the energy of transaction. This creates a mood and establishes a certain type of relationship between myself as the photographer, and themselves as the subjects. Then the work can begin between us.

We are surrounded by cameras − being surveyed all the time. There are lots of reality shows with juries. Nowadays people are waiting to be seen and to be expected. Considering such a situation − such a society in other terms − what are your observations in this process of casting for your photos?

Every motion in our private lives is potentially and probably stored in a digital history. And the average person not only doesn’t seem to mind, but embraces a chance to be ‘followed’.

The proliferation of cameras could make us more self-aware of the various ways we perform in everyday life. On the other hand, it also entrenches our performances and makes them seem more natural and inevitable. We share these images with friends, family and strangers who validate them, and in some measure, we interpret our own memories and happiness based on how many individuals ‘like’ the documentation of our everyday lives. The thrill of sharing is addictive.

It reminds me of the innovation of the Brownie camera in 1900 by George Eastman. Before the Brownie, letter-writing was how average individuals described their lives to loved ones from afar. The first inexpensive camera ever invented, the Brownie gave anyone access to photographing their lives for the first time, and as a result pictures replaced letters, and our communication culture grew visually. Something similar is now happening through internet sharing, time and space is collapsed. Participation yields to exhibitionism. There is a comfort in being watched. It’s an exciting and frightening time to see where this will all lead us.

When the people who are casted are asked to perform such a daily act as walking, pretending as a pedestrian, etc., how do they respond? You create a stage where everything seems a non-performed instant, however it is performed.

Generally, actors respond theatrically, but over time they become rapt in trying to get the finer and finer details of everyday movement. It’s an interesting process to watch. The skill of copying the way one walks, sips their drink, ties their shoes, is quite difficult to do well. The power to still the constant movement of time and frame the world as a dance is something I deeply value.

There is a great quote from Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities that I feel kindred to: ‘Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to the dance — not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any once place is always replete with new improvisations.’

Mirror, reflection of the self, lookalikes and the notion of doppelgänger – as in the series Double Walkers (2012) − is crucial in your photos. In history and literature there are two versions of a doppelgänger. Originally, seeing your double represents bad luck or death − in his short story, ‘The Other’, Borges sees and chats with himself as a young man, as a reminder of the end of his life. On the other hand, in Egyptian mythology it is ka: the exact counterpart, a resemblance. Which definition is appealing to you?

There are many instances in my personal history photographing on the street, where, undoubtedly, I discover the street is collaborating with me. Double Walkers is an example of that. I told a friend visiting that I wanted to make a picture of myself with someone who mirrored my physical description, a stranger, and wondered if such a thing was possible. The next day, I saw her. We looked just alike (as you can see in the picture). I timidly approached her and explained my need to photograph her, after which she said, ‘Okay I’ll do it.’ She then told me, ‘My name is Elizabeth.’ And I knew she was the one for this picture.

For me, this doppelgänger is both a terror and a comfort – terror in it reminds you of your limited existence, how small your life is in the eyes of others; but comforting in that for me at least, there is this magic on the street, a sisterhood, some sort of fate, a connecting fabric between me and strangers. So I do feel it works in both ways. I see myself in others and am terrified, because they are objects on my stage as I am on theirs. But then when that frame is breached, there are unexpected connections between us.

Why are you interested in this duplication, resemblance?

Photography is so good at collecting likeness in the world. I’m not as interested in duplication as repetition. Through repetitive actions in photographing, my consciousness shifts, into my life as an everyday person, to my world of picture making. In this world, I find uncanny harmony.

Pragmatically, I mean visiting the same spaces repeatedly, day after day, allowing for each experience to unfold and reveal exactly what I am looking for in that space, on that street corner with that person. Mirrors are a way to add a phantom, a body that looks like it is there, but is not real.

If I had to guess, I would say this fixation probably comes from my background in dance, my Christian schooling, and growing up with identical twin sisters.

Why are your models mostly female?

I am honestly unsure. While I was a Yale, a very special teacher, Rick Moody, asked me to give up my internal fight and just photograph women, because that’s what I obviously want to do. It was such a relief to hear. Generally I’ve learned from my own work and studying great artists, that the greatest work comes when artists meet themselves where they are, wherever that may be.

Which dance pieces influence you?

There are too many to name.

Pina Bausch’s ‘Rite of Spring’ brings speaks volumes about similar concerns, feel. Merce Cunningham must be mentioned, especially ‘Variations V’. I love how Martha Graham’s ‘Technique’ engages in the depths of repetition. The great works of theatre directors Romeo Castelucci and Robert Wilson are a must-see for anyone interested in these ideas. Bergman’s ‘Persona’ is an obviously huge influence as well. Lastly, the book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life by Erving Goffman is a must-read.