Interview: Esther Teichmann

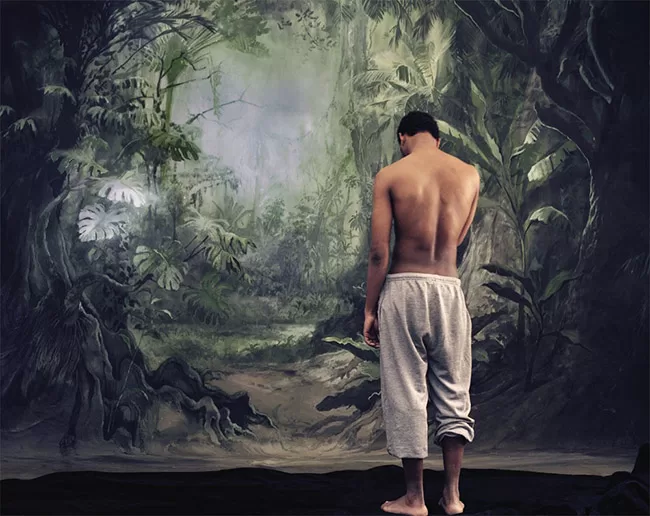

A tactile sense arouses after an encounter with the solitude of man in the mist, looking over the mountains a face the viewer would never be able to see. Subsequent to a meeting with any Romanticist painting, several questions and thoughts swirl in the mind: are we alone, or lonely? The atmosphere in the paintings of the German Romanticists, say, Caspar David Friedrich as an example, has a rigorous connection to where the painters lived. The geography and the culture of an artist may indicate more then expected. Nature, mist, darkness, melancholic persona: the enigma is solved. Esther Teichmann’s works with caves, trees, rivers, wet stones in the fog; bodies bathing, swimming and simultaneously interrogating – ornamented with paint and collage from time to time – contains within it the memory of her childhood lived in the Black Forest.

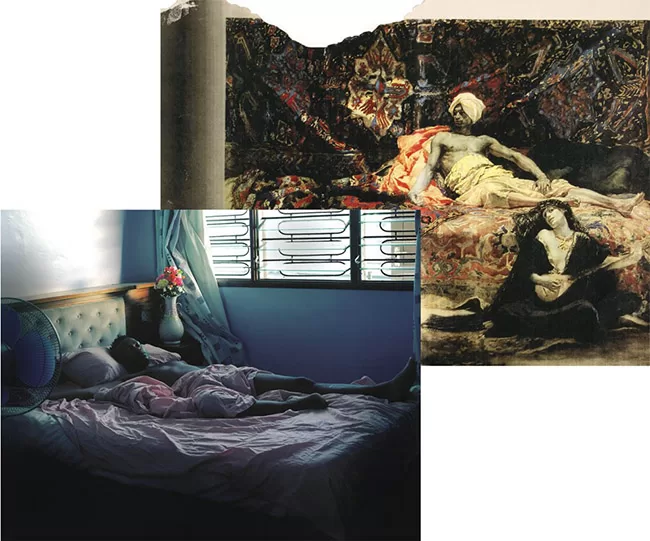

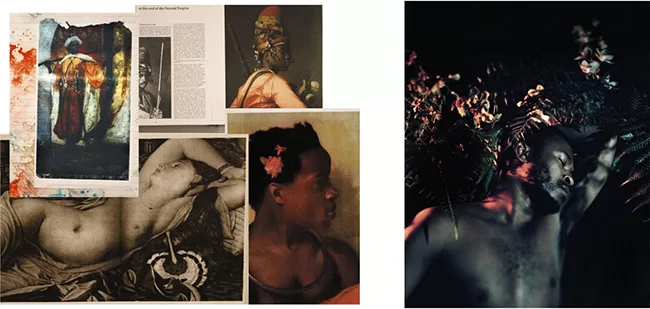

The uncanny yet beauteous is hidden in Teichmann’s photos. There is allure as well as burden. As mentioned before in several texts and interviews, the artist’s work contains influences from Grünewald and Cranach; Orientalist painters, too – Geromé shall be mentioned at the first place – and Ingres. Furthermore, the strong influence of Hans Bellmer, who was also a close friend of Bataille – one of Teichmann’s favourite writers – is evident. The dreamlike character in the works recalls legendary poet and painter Blake, and needless to say, Symbolism.

Another significant feature of Teichmann’s work is writing. In her texts the writer/photographer mainly alludes to love – the caressing love of a mother, or the arms of a lover – the erotic, the luscious, and the pure liquid and loss of a beloved one; death – grief and mourning as a result. All are blended in Teichmann’s photographs. Photos depicting heads of women and men in ‘Diptych’ (2006) or ‘Untitled’ (2004), from the series Stillend Gespiegelt, make one wonder: are they dead, or sleeping, or in the state of orgasm?

The famous bathers of late-nineteenth century paintings are also visible in the photos, however skin is not idealised. They are not odalisques nor Venus, nevertheless a certain otherness is ineluctable. Flesh exists with all the bruises, or the sleek skin emanates light. On the contrary, as in the series Viscosity (2004–2005), body or flesh is absent. We discern the skin depicted in water, stuck in the black and sinking slowly.

The model and the artist has been a significant topic in the history of art, especially the male artist and the female model. When the gaze is shifted how do we approach to the male body? None of Teichmann’s models, male or female, look directly into our eyes. In all probability, by not being aware of our presence, they prevent eye contact. A male body sleeping inside the tulles dangling, swathed in fabrics, enthralls the viewer. In ‘Untitled’ (2008) in Mythologies, the posture is reminiscent of the well known pose that Ingres worked on insistently and finalised in The Turkish Bath, 1862 – right-bottom of the painting.

A definitive distance is placed between the eye and the object. There is no doubt that a photographer is a voyeur, the cliché we all know, however one may question another thing: would it be possible to say that Teichmann’s gaze is female? Nowadays, is it really possible to highlight the triumph of the female gaze, or is it still dominated by a patriarch?

Perishables are attractive because of their limited time. One knows love, and the time we have in our hands, is about to disappear. At a certain point, all of us have experienced the sorrow of not being with a loved one, say, missing an instant. There is a poignant reminder of the lost, times that are lost while feeling sad about the lost; what-ifs, if-onlys, what-would-have-happeneds. Voids and emptiness… I ponder, does Teichmann capture the moment that has just vanished, in order to have it as an eternity to diminish the pain?

In your short essay, ‘Sleeping in Dark Rooms and Caves’, despite mentioning the relaxation as a result of swimming, you’re utterly drowning. In Viscosity there is lustrous skin suffocating in water. Your works usually limn duplication in relation to life and death, or joy/the erotic and death. Why do you have this strong bond with loss, the missing, or desire and melancholia occurring as a result?

I am really interested in the slippage between the ecstatic and the melancholic, between pleasure and pain and how you described letting go within water as in Viscosity, and how close this might be to a form of drowning.

That early series of figures submerged within a lake at night, rupturing the surface of the water, came from memories of swimming in the forest lake near my childhood home on humid summer nights. The exhilaration and eroticism of swimming naked in these black waters was always combined with the frightening impulse to keep swimming deeper and not resurface.

This duality of pleasure and a (self-)destructive impulse is one version of George Bataille’s thesis that a state of ecstasy may only ever be reached when we are aware (if only peripherally) of death or annihilation. This would explain the lure, the power of photography, which is predicated upon the ‘death’ of the object in the moment of its being frozen as an image. In Erotism, Bataille speaks of the discontinuous and distinct solitude of man (and woman), and how, paradoxically, it is together, while touching, that this gulf of separation is most dizzyingly apparent.

The whole business of eroticism is to strike to the inmost core of the living being, so that the heart stands still. The transition from the normal state to that of erotic desire presupposes a partial dissolution of the person as he exists within the realm of discontinuity…The whole business of eroticism is to destroy the self-contained character of the participators as they are in their normal lives. (Georges Bataille. Erotism: Death & Sensuality. Translated by Mary Dalwood. San Francisco: City Light Books, 1986 (19571, p. 17).

Once, when I told a friend that I feel like falling in my life, she interpreted my situation as a fall towards the beginning, to the open end. How would you describe the fall in your own work?

To fall is to give myself up, to momentarily lose control over my body, mind and subjectivity, handing myself over to another being or thing. Falling always demands that I ask myself whether I will be able to get up again. Yet falling is rarely voluntary. I feel it happening, feel the ground giving way, the vertigo of altered sense. We fall into darkness, into mourning, into love and into sleep, sinking into this otherness so sought and feared. We hope that should this fall ever end, the impact will not obliterate our very being (unless we are intentionally falling to our death). To plummet against gravity is to experience a shedding of the body as we know it. I fall towards and into something or someone. I fall through the air in an extension of time, an elongated moment. Falling is always bound to the risk of the complete dissolution and annihilation of the self.

‘The lost memory is not accidentally lost. It is lost rather in so far as it belongs to an area of my life which I reject…’ writes Merleau-Ponty in Phenonemmology of Perception (p. 187). To add another layer: memory also expresses itself through language. How would you elucidate the relation between memory and loss?

Forgetting is not only a biological part of our make-up but also a necessary part. Forgetting is perhaps as liberating as it is frightening and dangerous.

In Harald Weinrich’s book, Lethe: the Art and Critique of Forgetting, he quotes Goethe saying of himself on forgetting that ‘an ethereal Lethe-stream runs through and quickens all of life’ and that he has ‘always known how to treasure, use, and intensify this sublime divine gift.’

From your own perspective how do you reinterpret the bather of Ingres or Geromé’s young boys, or, say, Venus as male. How do you differ the body belonging to the history of art, and how do you pertain to this body in your work?

Rather than working directly from specific art-history I collect material from various sources, from the Renaissance and Orientalist paintings you refer to, material too from newspaper clippings and film stills and pin them up in the studio. These bodies, their gestures and narrative potential, become loose references, which I then build upon.

How would the series Mythologies be without your interference by painting? Is adding another layer by painting never being satisfied with what is in the hands?

Whether in the studio with backdrops and lighting, or out on location, I am interested in creating this otherworldly fictional space of desire and longing, and painting onto the images allowed me to loosen it from its photographic referent. Suddenly I could move more fluidly from studio to landscape. The images were no longer as clearly geographically located – whether photographed in caves in Germany, in swamps in Florida, in waterfalls in upstate NY or California, or in the jungle in Kenya or Australia – the spaces become one through palette and a working into the image, dripping in psychedelic inky hues.

How do you see/feel the skin of the other in the instant of taking the photo?

Jean-Luc Nancy echoing Barthes describes a ‘photograph [as] a rubbing or rubbing away of a body’.One skin becoming momentarily another triggers a yearning for the lost skin and a confusion between presence and absence. ‘The gift is contact, sensuality: you will be touching what I have touched, a third skin unites us.’ (Jean-Luc Nancy. The Ground of the Image. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005, p. 107. Roland Barthes. A Lover’s Discourse. London: Penguin Books, 1990, 19771, p. 75.)

In Classical or Orientalist paintings we encounter the skin, whereas in your series Mythologies, you don’t idealise the skin. Furthermore, the flesh greets us. On the contrary, you never mention the flesh in your texts. Do you agree? If yes, why?

Quite the contrary, a whole chapter of the book I have written and am in the process of editing is about skin, the skin of the image, of mother and lover, looking at what it is to feel alive through the body and skin of another. Waiting for and anticipating the return of the mother, of her touch, her skin, is a delirium first experienced in the childhood fascination with the image of the mother, and re-encountered later with that of the object of one’s love.

‘The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, that was there, rays went out that came to touch me, me who is here…the light, although impalpable, is certainly here a carnal medium, a skin that I share with he or she who was photographed.’ ( Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. London: Vintage, 1993 (19801), p. 80.)

This play between light and skin, between the photograph and emanations, can be registered in the French word for ‘film’: pellicule. From pellis, the skin pellicule and ‘film’ originally have the same meaning: a small or thin skin, a kind of membrane.

The women in Mythologies, are they dying or are they in the state of orgasm?

Both… maybe orgasm is one of the few moments of loss of control in which we are somehow both absolutely present and outside ourselves – an eradication of self and perhaps an intensification simultaneously.

How do literature and your own texts merge with your photography?

Literature, cinema and my own writing are crucial to my process of making and thinking about images. I often write images before I make them as visual objects, or write stories based on the images and experiences of them. In the process of writing, my own memories and autobiography become fictionalised, characters based on existing people blur into one another taking on the shape of someone else.

Writing is crucial in your practice. In the texts of your book, Drinking Air, the narrator is neither a she or a he, maybe both at the same time like the character of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. As a woman do you think your gaze is female? As a shift, can we say that you are the one who is ‘othering’ or Orientalising the male body? How do you foresee the change of the gaze on the male body?

In terms of gaze, ‘othering’, and gender, I am interested in addressing the perhaps inevitable process of objectification that takes place with the photographic encounter, the exchange between photographer and subject. I think my gaze can be nothing other than female, and yet I acknowledge and am interested in this one being one of an othering and eroticisising, and exoticising of my subject. Perhaps the process both of being objectified and of objectifying, regardless of gender on either part, although always complex, can also be one of pleasure. Looking and being looked at as image – as an image of desire and love, as well as a fascination with the otherness of that which is not us. And yet in many ways all of my images, regardless of whether they are of lovers, sisters, strangers, friends or my mother, are more self-portraits than they are an image that says something about the body and subject depicted.

In her book This Sex Which is Not One, Luce Irigaray mentions the auto-eroticism of the female body as a result of the form of the vagina, and how female sexuality is underestimated. You have a new solo exhibition, Fractal Stars, Salt Water and Tears, opening in London at Flowers Gallery with a book launch. In this exhibition, female nudes ‘punctuating mythical landscapes, auto-erotic in their gaze and gesture’ are depicted. How did this topic arise?

I guess from exactly what Irigaray is speaking of, how female sexuality is underestimated perhaps even by ourselves as women, and the perhaps life-long discovery of the pleasure our bodies are capable of producing. I was interested in talking about this process and the mystery of desire and pleasure, as well as looking at the intensity of the relationship between women, looking at mothers and children, sisters and friends. The short story in the book that launches with the show describes falling in love with a man because he feels like home in a way that only women ever have. There is a melancholic eroticism throughout the book and show.

Extract from the short story, Fractal Stars, Salt Water and Tears, from which the show gets its title:

She thinks of the bodies and skins that had been as familiar as his was becoming, the strangeness of intimacy. She remembers the first time he undressed, her breath stuck inside her, gaze falling upon the fractal scar that spread across his chest. It begins at the base of his throat, in that soft indentation between two arteries, glistening a coral pink like the inside of the seashell she holds to her ear to fall asleep. From this tender point it spreads out and down like the finest of seaweed, fossilized upon him in one violent moment. As she touched his lightning scar, V knew it had become her map, the body it was etched upon her guide.

She keeps a thicker kind of seaweed in her bathtub, the brackish sweet salty smell reaching her boat-bed when a breeze moves across the room. She keeps these washed up branches of slippery leather, as soft and wet as inside herself, so as to bathe within their drowned mermaids’ embrace. Filling the bath with warm water, V lowers herself into their tentacles as he sleeps oblivious, a few feet away.

As is the sea beneath them, so is her heart. Full. Roaring. She tastes her saltiness in his mouth, the taste of the ocean, sweet smell of swamps. Deep sea diving, eyes open, swimming from luminous turquoise into dark blue towards almost black waters. Unafraid, she swims deeper, through ocean caves, no longer needing to breathe. With a calm urgency she swims down towards home, past and with all the women that are a part of her. Long adolescent summer-evening baths with her best friend. Languid days spent reading side by side on burning rocks next to waterfalls. The contentment of each other’s company. The soft downy hair of his armpit feels like the cradle next to her mother’s breast in which her head still fits exactly. She wraps herself around him the way she and her sisters used to sleep entwined, slowly realizing she is no longer homesick. Full. Roaring. Unaware tears stream down her face, her body weeping with relief.

Fractal Scars, Salt Water and Tears, will be on show at London’s Flowers Gallery, 4 April-10 May 2014

SPBH Book Club Vol V by Esther Teichmann, will be released Thursday 3 April 2014 through Self Publish Be Happy