Interview – Jillian Freyer

I left my apartment in Brooklyn last week and I went upstate to visit a friend of mine. I always feel shocked when I realise how dependent I am on the sounds and the smells of the city. It makes me understand how alienated I am – incredibly addicted to street food odours and ambulance sirens. Getting off the bus, in the middle of an unfamiliar countryside, I suddenly hear and smell sounds and flavours I thought I had forgotten – my mind travels back to a familiar landscape that is miles away from here. It’s like when summer comes and we suddenly experience the heat that felt impossible during the freezing winter. Our bodies awaken again, like bears after months of hibernation.

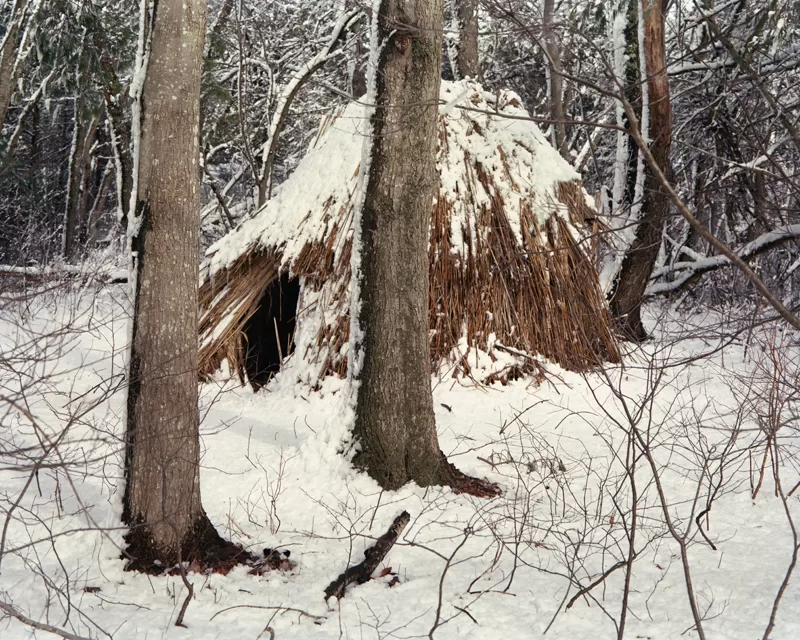

Jillian Freyer‘s photographs are all of this. They recall that juxtaposition of the childish anxiety of finding yourself lost in woods, but at the same time being comforted by the feel of primordial nature – no sounds aside from the breath coming out of your chest and the whispers of the trees. Suddenly we remember those very first years of our life, probably the only time when we instinctively understand nature. The curious thing is that I feel I can hear her images, more that I can see them. It doesn’t matter if it’s the portrait of a man in the middle of a natural landscape or it’s a close-up of a frozen lake; without thinking, I feel that story belongs to me as well. And immediately I think that the impulse of escaping is rooted in all of us.

The feeling I have when I look at your series Wildwood is the one of that moment of the year when the snow starts to melt down and the soil and frozen grass begin to see the sunlight after a cold winter. It’s a sense of rebirth or a re-discovery of something very familiar that for a strange reason we had forgotten. How much of your relationship with nature influences your work? Is this earthy connection something present in your photographs? And why?

Absolutely! My relationship with the natural world is certainly present in my photographs, and in more ways than I think I was initially aware of. I grew up as the oldest child, the first few years of my life consisted of playing on my own, and often times in the woods. Later on, my sister, cousins and myself would dress up in play clothes, build dams and walk barefoot through the wetlands behind my house. Fallen trees became lumber for our forts, and throughout these adventures we would be casting ourselves as characters in some elaborate story. The smell of the mud, how it felt between your bare toes, raspberry thorns scratching at one’s legs – these slight details are those that have remained with me and I find myself to this day making note of subtleties, and appreciating what the natural world provides us with, both physically and experientially. The woods were and still are a place for discovery; some parts remain wild and unknown and others I frequent more often, careful to pay attention to details that set a certain wood apart from the others. I relate these places back to the first memories I have of creating fictions, my mind swollen with imagination.

The subjects in your images are outsiders that have decided to leave the noisy streets of an overpopulated city to move back to nature. They are animals rediscovering an instinct that was completely buried in their souls when they were living in their urban landscapes. Now, they survive by looking at the stars, or the migration of birds, or by observing the biological changes that periodically happen in the forest around them – trees, lakes, skies. Do you think your story is about exile and a certain refuse of our contemporary life? About finding the animal instinct that must still be somewhere in our DNA but for some reason it seems to be lost?

For me, the story isn’t about exile necessarily, but more along the lines of escapism. I always think of this narrative in an indefinable place in time, not necessarily present. I think that this narrative is a combination of interests – film, literature, and possibly the current status of the environment and our future on this planet. I use photography as a way to learn about things I otherwise wouldn’t have access to. As Margaret Atwood says, “I write as if I’ve lived a lot of things I haven’t lived”, and I believe photography allows me to function in this way.

I began photographing this series with certain individuals – a man who fed the crows, a pig farmer who would ride the swine as well. One subject leads me to the next, allowing myself to learn about these alternative trades and individuals I wouldn’t normally come in contact with. The camera allowed me to work collaboratively with them, but with an extreme perspective, re-appropriating gestures and moments alongside seemingly unrelated landscapes.

A sense of solitude is also omnipresent. I can almost hear the sound of the wind but I can’t hear any voices. Just the sound of cold air choking out of your subjects chest. They are not part of the same herd of animals; they are solitary beings, hunting and constantly observing. Photography can be a lonely activity too. I think of Ansel Adams, walking his way deep into the wild of National Parks to photograph natural monuments. I wonder if you work in a similar way, if you see photography as a lonely activity? How do you take images and when?

My practice is definitely a lonely or solitary activity. Aside from the subject who is being photographed, I am very particular as to who accompanies me when I am out exploring to make photographs. It’s meditative for me, an escape – I have to be able to bring myself to another place, imagine a story line and take it out of context. Until recently, I rarely went out with others but I am finding that I am really enjoying when I do have the company of a close friend, and have the opportunity to receive their input.

I was surprised there were no images of animals and if there are any it’s just the idea – a fur, some footprints on the snow or some birds flying far away in the sky. As if in a way the natural rule of survival imposed itself again, allowing the humans to dominate other species. I guess I am curious to know if you think of natural hierarchy, or, more superficially, why animals are excluded in your world? And has any particular book inspired you? I keep on thinking of the dreamlike creatures that populate Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream.

I’ve certainly tried to photograph animals, but I find myself bothered with the fact that often times I am not in complete control, or I have to work alongside a trainer or they are fenced in. It doesn’t allow me to work in the way in which I try to disguise an atmosphere. I am a huge Michael Haneke fan, I love the way he only ever suggests events, usually violence. However, Haneke once said, “for me, it’s far more efficient to mobilise the imagination. It’s far more efficient to hear a creaking step, for example, than to see the face of a monster…” I feel as though I am doing something similar with the traces of animals, showing traces and hopefully raising questions rather than simply providing a photograph of an animal. I am interested in the psychology of the character and I’m not sure that an animal can provide that at this moment.

As for specific books, I first began making these photographs while reading the book Housekeeping, by Marilynne Robinson. It’s a fictional story about two sisters and their relationship as well as the landscape they inhabited. Robinson describes the cold, the sound of a frozen lake cracking more effectively than being there in person. Nothing compares to her luscious descriptions!

Nature and storytelling have a great tradition in the history of photography. I think of the first work of Justine Kurland for example and I wonder, what is your main inspiration or what you feel has been essential in the creation of this series?

Well, as I mentioned earlier I am extremely influence by films, and literature and a number of individuals such as Vali Myers – one thing leads me to the next exploration. Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson, The White Ribbon and Time of The Wolf by Michael Haneke, Night of the Hunter and Borgman — the majority of those titles deal with a secluded or minimal community and focus on the psychology of the individuals that inhabit them.

How much do you stage your images? Do you work intuitively or is your process a meditative and slow one?

A lot of the time the idea formulated for an image takes place over the course of a few months. If it’s September and a certain location looks best in August I will wait until then to photograph it, checking back periodically just to be sure! I love to take the time and develop a ‘character’ through research, watching films and finding the right person, both personality wise and physical attributes. Though personality is almost more important, I need to know we will work well together. The actual making of the photograph is usually very quick.

Getting lost and being found is something I cannot get out of my mind while I scroll the images on your website. Its like a play, where the characters chase themselves and sometimes they find each other but then they just get lost again. Its romantic and scary at the same time. And photography seems to be the perfect medium to illustrate this primordial hunt/chase. I think of photography as an essential tool in the path to conquer knowledge. What do you think of the binomial photography-knowledge? Do you think photography can tell us the truth?

Photography is definitely a tool that allows the author to tell a certain type of truth, depending on what their motive is. There is no way of ever revealing an unbiased truth, for if we take the initiative to make work about a certain subject, we must have feelings about it in one way or another. Photography has the ability to represent objects and people as they are in real life, but this doesn’t mean it is the truth. A teacher once asked my class whether we were interested in “taking photos or making photos”. Photography obtains the ability of telling the ‘truth’, but it all depends on which truth you are interested in telling.

All of my images, the gestures, the men sleeping in the reeds, the fur frozen between the ice all occurred, but the narrative in which it is organised within allows me to create a new truth and a new relationship between each character and event.

The surroundings in your images are not specific by any means. Those trees, forests, lakes and skies could be pretty much anywhere in North America or Europe. How do you choose the places you set your stories in? Is there any specific connection between the places in your series and you? Or is this anonymity something you want to go for?

A lot of these locations I make my photographs in I have a relationship to. I visit them frequently, they become reserved in a sense for my photographs, a place I retreat to and remove myself from ‘real life’. The New England landscape, which is where I make most of my photographs, also serves well because it is completely anonymous. I steer clear from landmarks or signifiers of a certain place. I don’t want my viewers to be able to place the location, and I think that this intention goes hand in hand with wanting these images to exist without being of the present or past.

What are you working on these days? Do you have any interesting project coming up?

I’ve been making a handful of new photographs, returning to a body of work I began last summer, and embracing the new seasons that are approaching. I’ll be starting my MFA at Yale this coming fall so I am feeling extremely excited to have a new location and community and new parameters overall to be working with.