Interview: Jonny Briggs

Familiarity, 2013 — My mother and sister sharing a yawn

The Other Side, 2013

Jareh Das: Your practice has always dealt with your relationship with your family, often examining the role reversal between parents and children. It strikes me that your most recent works, having seen both Ancestral Home at Simon Oldfield and Family Politics at Jerwood Space, focus more on the home and its role in the formation of memory. Could you describe your childhood home and its significance in your overall practice?

Jonny Briggs: There’s a term in cognitive psychology called ‘context dependent recall’, where if we revise for an exam in the same place we are to be examined, we are far more likely to improve our recall. It is as if our memories are stored externally from the mind, acting as cues to spark off past thoughts, feelings and events. I often entertain thoughts along these lines about my childhood family home – within which my parents still live. There are so many layers of memories there, which is at once comforting and confining; a comfort blanket of the known and a safety bubble of the familiar, which can be so hard to pop.

I remember childhood stories of fairy tales, C.S. Lewis and Enid Blyton, which I would imagine happening at particular trees or parts of the woods around the house. Now, as an adult, when I wander the woodland, all that magic is still there. The home involuntarily transports me back to the past, and I repeatedly choose to return. In some ways I see this as an uncomfortable comfort blanket, in that it can make things feel static and distance me from the present.

We are a family of hoarders, where items are kept as a way of clinging on to the past. Billowing boxes fill many rooms, shelves are filled, stuff is precariously placed on top of stuff. First pairs of shoes, greetings cards, family photographs, clothes, heirlooms and gifts produce the feeling of a museum of our own pasts. Beyond this, the home is a merging of my parents, my sisters and myself. It’s a place where all our biographies entwine, and is manifested in the objects and space.

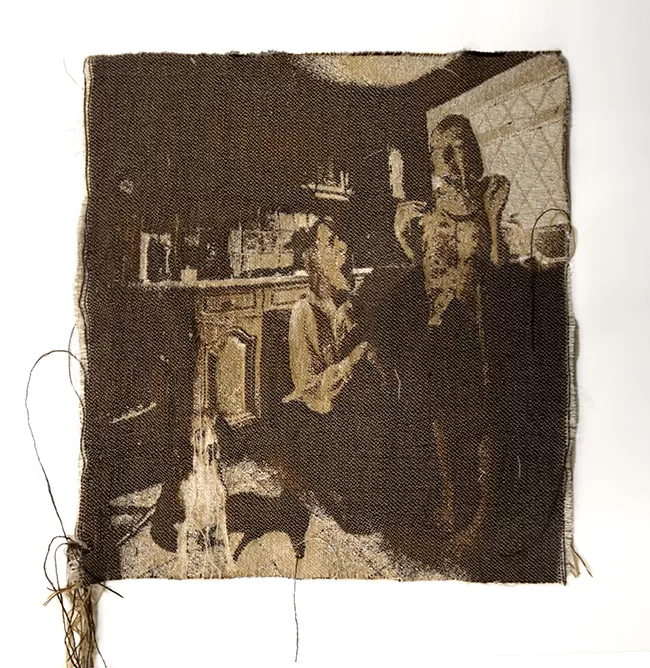

There is a predominance of browns, magnolia and beiges like hair and flesh, both in the home and my parents’ clothing. I sometimes see my parents as camouflaged within their surroundings, and the colour leaves me feeling subdued, heavy, and attaches me to the ‘normal’ I have been socialised into. Walking through my home is like walking through a sepia photograph.

I sometimes see the work as an escaping or at least perversion of the home, yet so much of the work is made within it. Props, scenes, tapestries and photographs have infiltrated it, and so the work is starting to become it – in this sense the work is short-circuiting itself. The home has become the work, and the work has become the home. I sometimes see it as an infiltration of my gaze.

I was particularly struck by the description you gave of the home of your grandmother, the yellowing of the walls from cigarettes in comparison to your grandmother’s smoking. I was interested in this relationship between domestic spaces and the people that embody them. How did you negotiate encountering this space and how the disease seemed to inhabit the space as well? It’s almost as if the invisibility of cancer was being made visible in an unconscious way.

You could say my grandmother’s house was introverted, hidden at the end of an estate behind overgrown trees that cast dark shadows across and inside the home. Each time I would visit, the thick atmosphere of smoke would cling to our clothes, the stink lingering for the rest of the day. More so than my parents, items were hoarded, with multiple packs of greetings cards, tissues, baskets, sugar, gifts and many other items forming mounds of clutter. The smell of cigarettes was overwhelming and left a thick residue on the interior of the house – and inescapably the interior of Grandma’s body. The windows gradually became glazed like cataracts from the stains. Cupboard doors became wonky, leaks would appear, mould would spread, dirt built up, and clutter increased. My grandmother would sit in her patterned yellowing dresses, almost invisible amongst her possessions. It was awkwardly profound to notice the photographs of the family start to fade under thickening yellow smoke stains, and when they were taken off from the wall, it became apparent that the photographs of family had shielded the walls of her home from the encroaching layer of yellow, and only the ghost of them remained. I wonder if I had linked this spreading dull yellow with the spreading cancer – I resented the colour.

I found it hard to visit there. Beyond the unpleasant smell, the sight of it and the gathering dirt, it felt like I was walking inside of Grandma’s body. They both deteriorated in parallel, so each time I would visit it was a daunting reminder of the state her body was in. The yellowing walls and atmosphere were like her lungs, the leaks reminded me of her organs, and even the attic reminded me of her mind, with all these memories categorised and packaged away in boxes.

The experience pushed me to see the home as a metaphorical body, and reminded me of moments in my life when I’ve had a loss, whether a bereavement or coming out of a long-term relationship. In these moments I’ve noticed a pattern in my behaviour, where I’ll rearrange my living space. I’d sort through my belongings, get rid of old things, rearrange what remains without even stopping to question why. It was almost as if I was rearranging the external as a way of rearranging the internal. Yet again, it’s a reminder of how we make our environment, and our environment makes us.

I think an interesting point is raised in this question about making the invisible visible. The spreading cancer was something I could not see or grasp – it was something intangible, and it’s almost as if I had to make it visible by representing it metaphorically. Both in the way I saw her home, and also in how I make artwork – to make the intangible tangible. To give the unspoken a voice.

Dummy, 160 x 45 x 45cm, 2013, Sculpture; mixed media

Dummy (2012) must have been a hard piece to associate with, from working through loss and the invasive nature of a disease like cancer. Could you go into some detail about realising this work (which really, in my opinion, is quite a remarkable and complex piece)? What happens to the piece in terms of its life span and how do you continue to deal with the loss tied to the work?

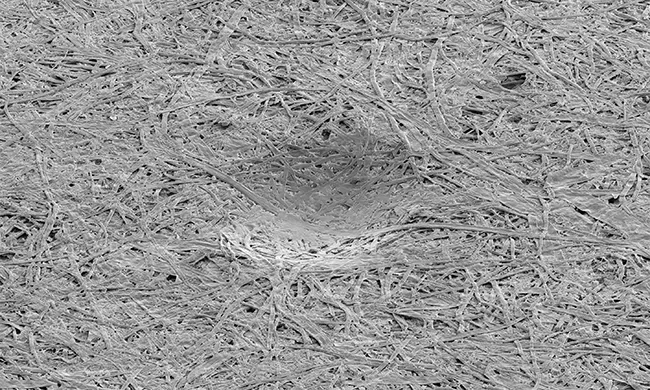

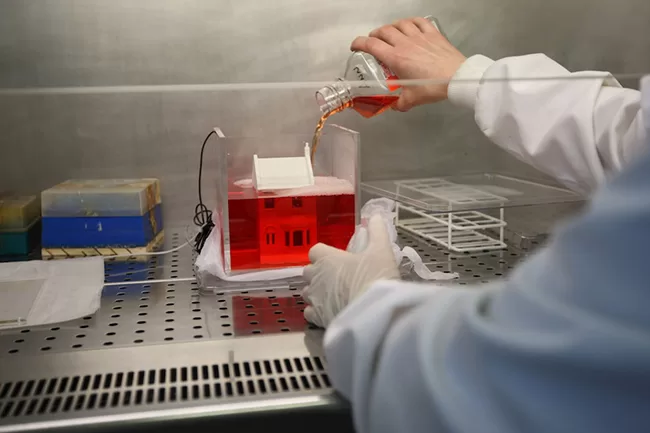

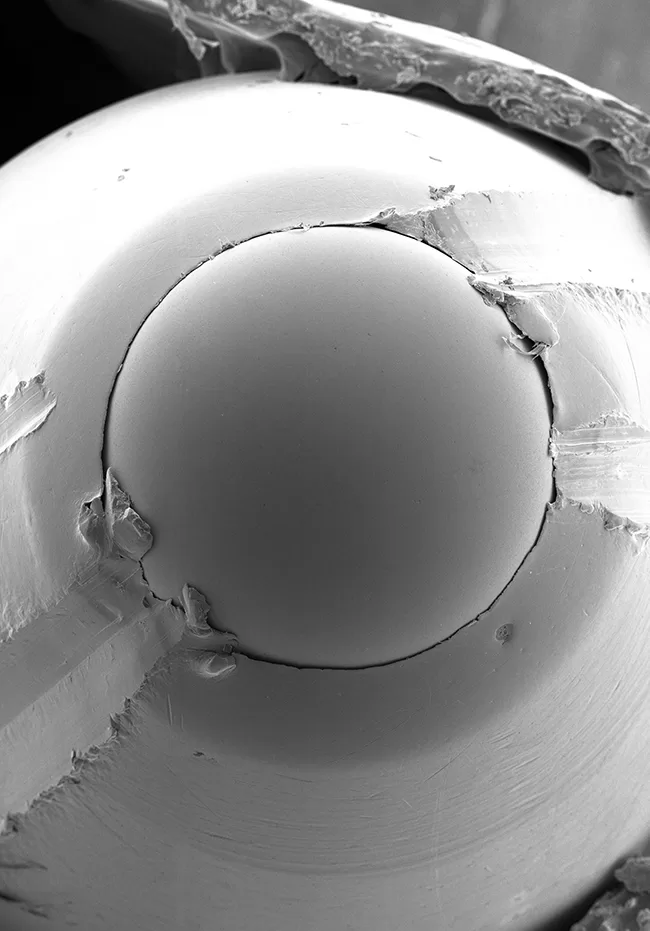

I was working with a group of scientists at Herefield Hospital who helped me to grow a small house out of human cancer cells. They were so supportive and really got behind the ideas to make them happen. It took just over a year to realise the idea, though through speculation and testing it started to become a reality. Seeing the cells in the microscope really threw me. I found myself willing on something to grow that I used to associate with destruction.

The cells were applied upon a ‘scaffold’ that supported them, which was immersed in a translucent red liquid called ‘medium’ that fed the cells and kept them at the correct Ph level. I connected with this word medium, as it reminded me of a way people seek to contact the dead. The liquid was kept at a constant 37.5 degrees Celsius and was transported from the laboratory to an incubator in the gallery. The environment in the incubator made an artificial body; as far as the cells were concerned, the house was a body. The title, ‘Dummy’, refers to an object that mimics the body – like a crash test dummy, or a baby’s dummy as a surrogate breast, linking back to childhood attachment to our caregivers. Dummy is also referring to something fake – to something that isn’t there. Again, this links back to the invisible made visible.

The laboratory explained that even though the piece was made in sterile conditions, even if the tiniest amount of bacteria were to be in the inner sealed cube of the incubator, it would spread throughout the liquid and end up being a battle between the bacteria and the cancer. Over two months the cells within the incubator grew as a film over the house. The medium became murkier and decreased in quantity, and eventually changed colour to pink – signalling a bacterial infection. As a result, the cancer cells would likely have died from toxins let off by the bacteria – again this cycle of growth and decay, of life and death. Each time this piece is exhibited, a new house will be made with a new fate.

How is science having an impact upon your work and what led to, or inspired, art-science conversations in your recent works?

Rather than science choosing the ideas, it was more so the ideas choosing science. My practice has always been multi-disciplinary, and the idea just made the most sense to me in this medium. It was more a case of how the ideas could be realised, and these took forms that were different to the rest of the work. Regardless, I have been interested in science for a long while, starting a part-time foundation degree in astrophysics last year which fascinates me. Simplistically, I sometimes see science as seeking facts, and art as seeking ambiguities; the art piece as asking questions, and the sciences attempting to answer. It’s no wonder an interest in the merging of the two disciplines is so exciting, with organisations such as the Arts Catalyst, Wellcome Collection, NESTA and the Art Science Prize. Rather than seeing disciplines as separate and distinct, there are so many more possibilities when the boundaries between these disciplines are blurred.

Close to home series, (top) no.22, (bottom) no. 29;

digitally altered family photographs partially montaged back on to their unedited originals and pinned to the inside of brown stained box

Close to Home series, installed at Jerwood Space, 2013, photo courtesy of thisistomorrow.info

You have refashioned the traditional family album in the Close to Home series, by substituting parents for children, something you’ve explored in earlier works. Can you shed some light on these morphed, montage identities you have created that shift the meanings of traditional perceptions of the family album?

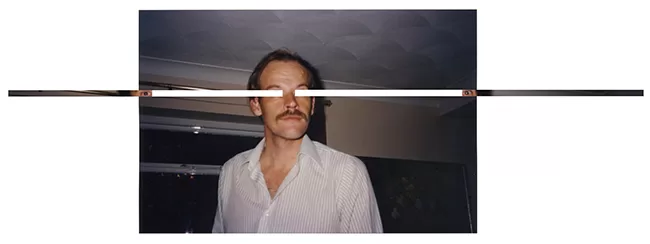

Close to Home involves digitally altered family photographs, which are physically montaged back over their unedited originals; juxtaposing two constructed realities. Both my mother and her mother’s heads are montaged on to the bodies of the children, flipping roles, relationships and situations.

When I was younger my father and I had a difficult relationship, and perhaps because of this I desperately wanted to be part of my mother and four older sisters’ world; to wear the same clothes, play with the same toys and even go to the same public toilets. It was at a stage when I didn’t yet understand these complexities of adult life and the sacrifices required in order to follow them; I just wanted to be part of the social group.

Through this new body of work, the inaccessible tribe of my sisters is shown, often with myself appearing as if I shouldn’t be in the photographs within this other world. On the surface it appears to be a place where my father is absent – yet he is ever-present as it is his eyes behind the lens. His gaze dominates the series, and therefore this could be seen as juxtaposing my father’s gaze and my own.

The domino effect of inheritance emerges alongside notions of conformity, closeness, and rituals. The domestic shrine-like installation and imposter colours (magenta and cyan), shapes and characters remind me of portals to another world. Referencing my religious upbringing and aspects of the supernatural, these take inspiration from photographs of suspected poltergeist activity and domestic disturbances.

In some of these altered family photographs, you have removed the eyes. I’m reminded of Peggy Phelan’s observations that the formation of ‘I’ cannot be witnessed by the ‘Eye’. In other words, we don’t recognise our self through our eyes. Do you think that your works through the camera’s ‘eye’ somehow communicate or capture some of how the self is formed?

The gaze is an important aspect in the work – beyond myself as a photographer looking through the lens, there is often a wish for the works to look back at the viewer, to return the gaze. The work could be seen as a rebellion against my father’s gaze from behind the lens when taking our family photographs. Whenever I take photographs of him or my mother, I suddenly feel in control, like there has been a power flip, that now it’s about the way that I see, unveiling an alternative family story.

I’m reminded of times in public, when I realise that someone is looking at me; or even worse, our gaze meets. In that moment my mind splits into my fears and desires – that they are either attracted to me, or that they want to start a fight with me. That they think that I am attracted to them, or that I want to start a fight with them. It’s no wonder that so many people find it hard to look others in the eye, that when we look at an image we gravitate towards the eyes of the subject, and that fights so often start with the phrase ‘What are you looking at?’

I often entertain the thought that what our parents, grandparents, and all those around us say to us – and even words and language in themselves – can categorise and shape the way we see the world around us. Our memories can cloud the way we see, and it is these artificial perceptions I wish to think beyond; to detach myself from my adult assumptions and see the world afresh like a child again. Because what we perceive can be a projection of our own fears and desires or tainted by our memories, I identify with Peggy Phelan’s observations. In this sense the work could be interpreted as how the conditioned self is formed, which reminds me of Narcissus, upon tearing out his own eyes exclaiming, ‘Once I could not see, but now I can see.’

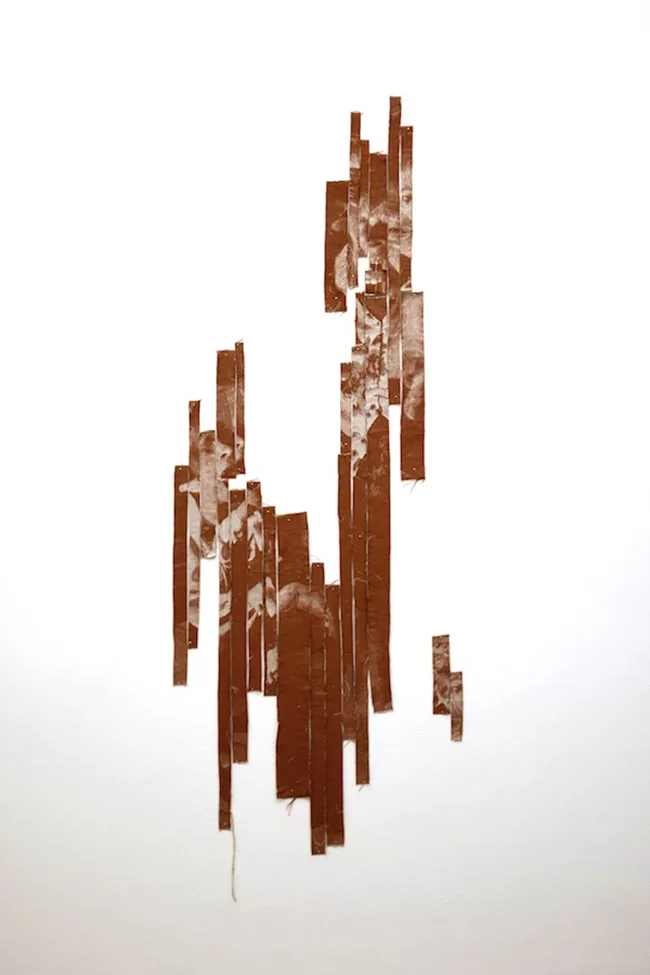

Forward Slashes, Altered family photograph, 2013

Schisms 7, Sister’s head upon my body, Adapted family photograph, 2011

A shared yawn, 2013

Envisionaries installation shot, 2013

Medium, 2013 — Electron micrograph of the tip of my Father’s pen