Juan Brenner – Tonatiuh

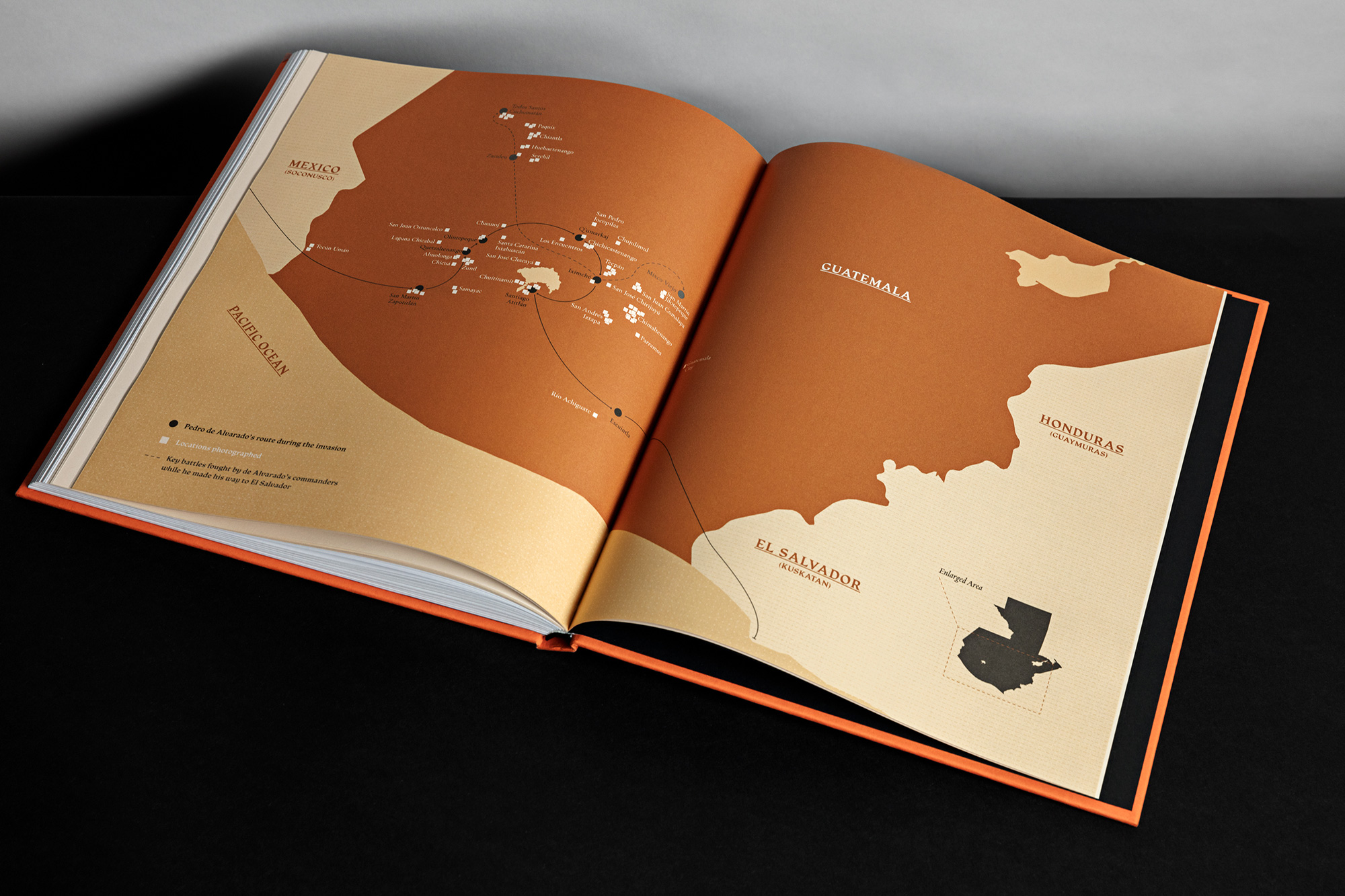

A half-millennium ago, a Spanish conquistador named Pedro de Alvarado wreaked havoc throughout Central America. Alvarado waged campaigns in pursuit of gold throughout modern-day Mexico, leading massacres and destroying indigenous communities in the process. Pre-Columbian temples were destroyed and replaced with Christian crosses. Indigenous leaders were executed. Alliances with tribal communities were made and broken. Societies throughout the continent were forced to choose between destruction or fealty to the Spanish crown. As Alvarado rose in rank under command of Hernan Cortes, the leader of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, he was tasked to turn south, conquering the modern-day nations of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Now, five-hundred years later, the spectres of Spanish colonialism still haunt the region.

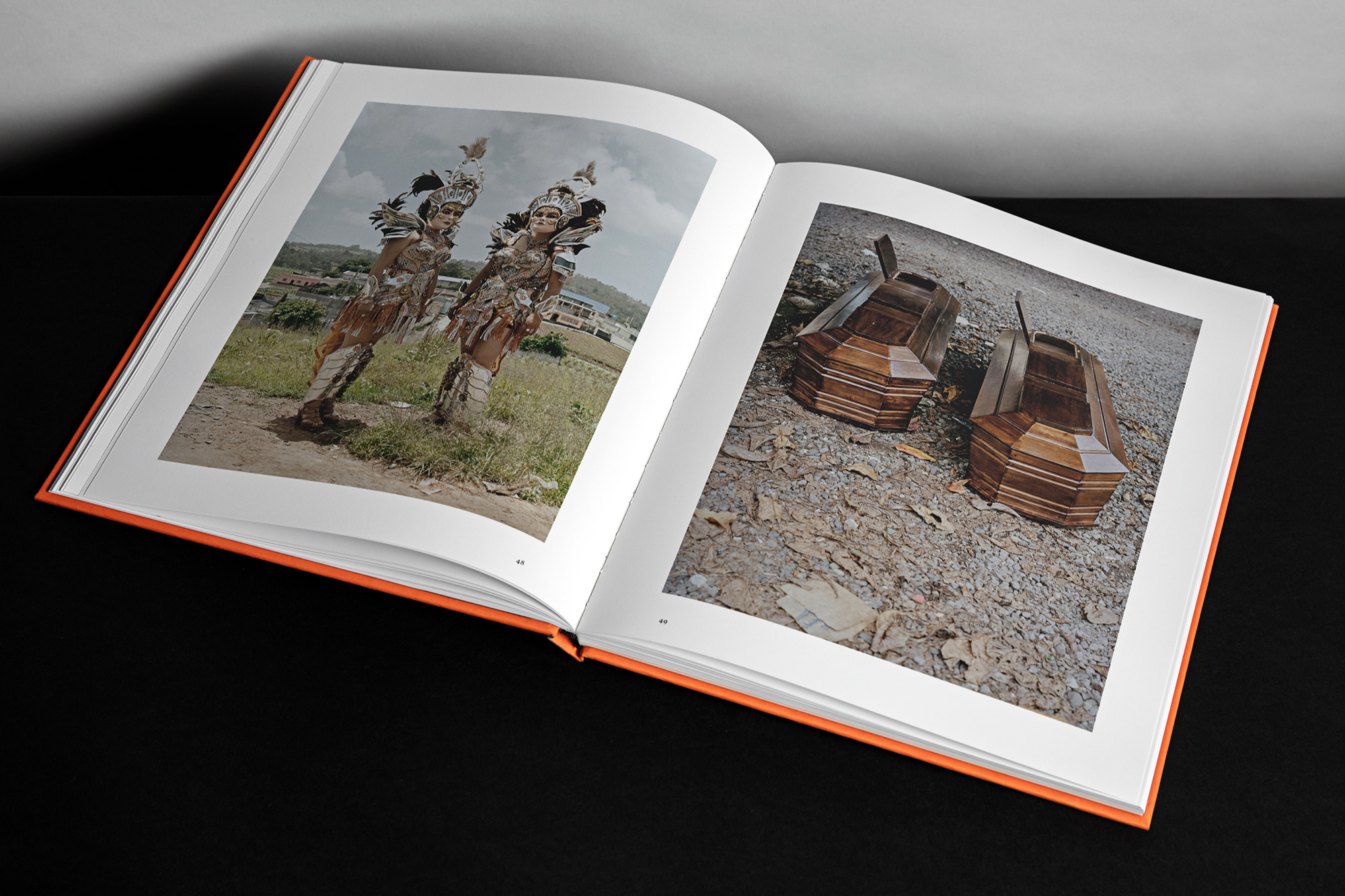

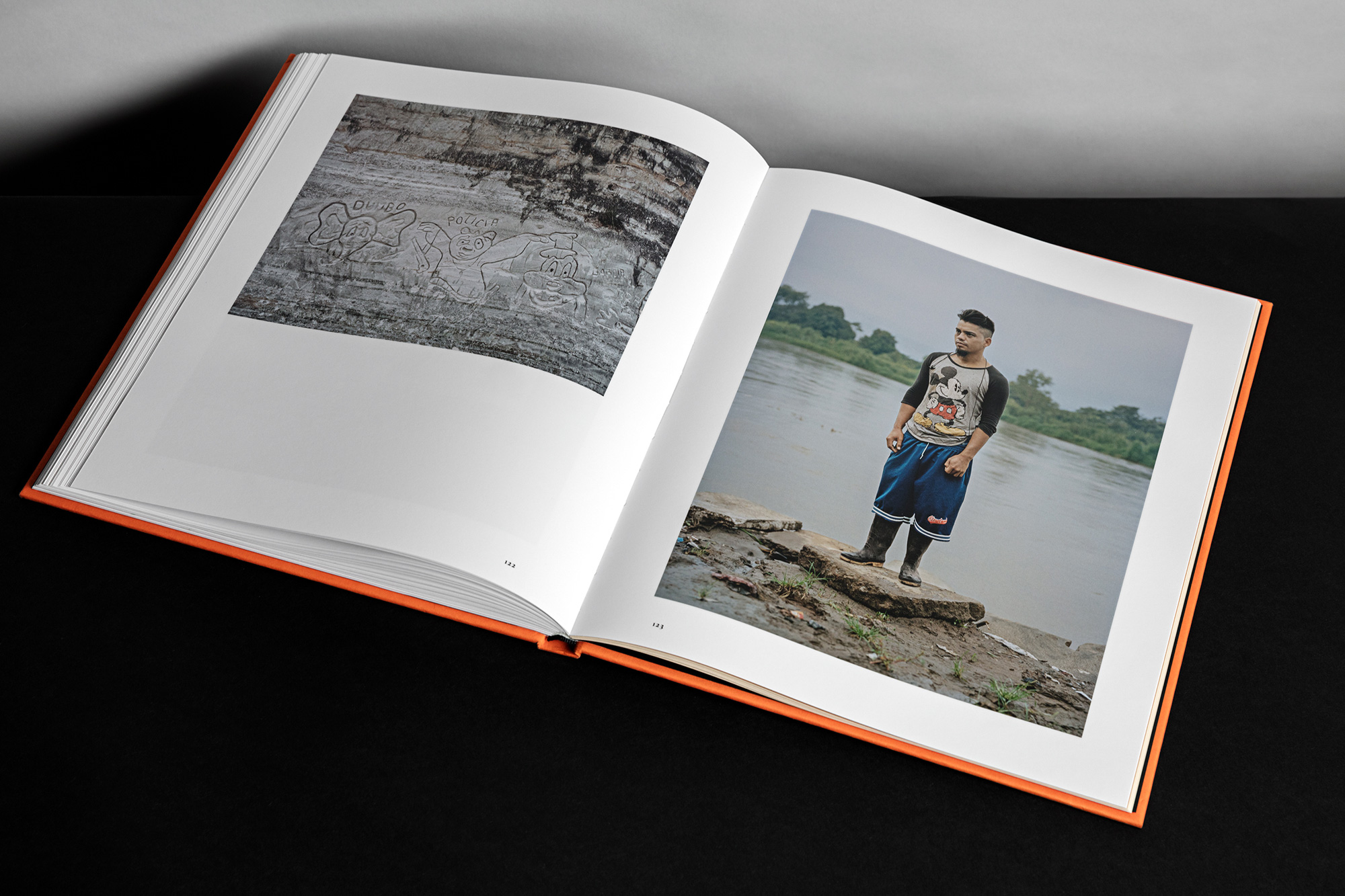

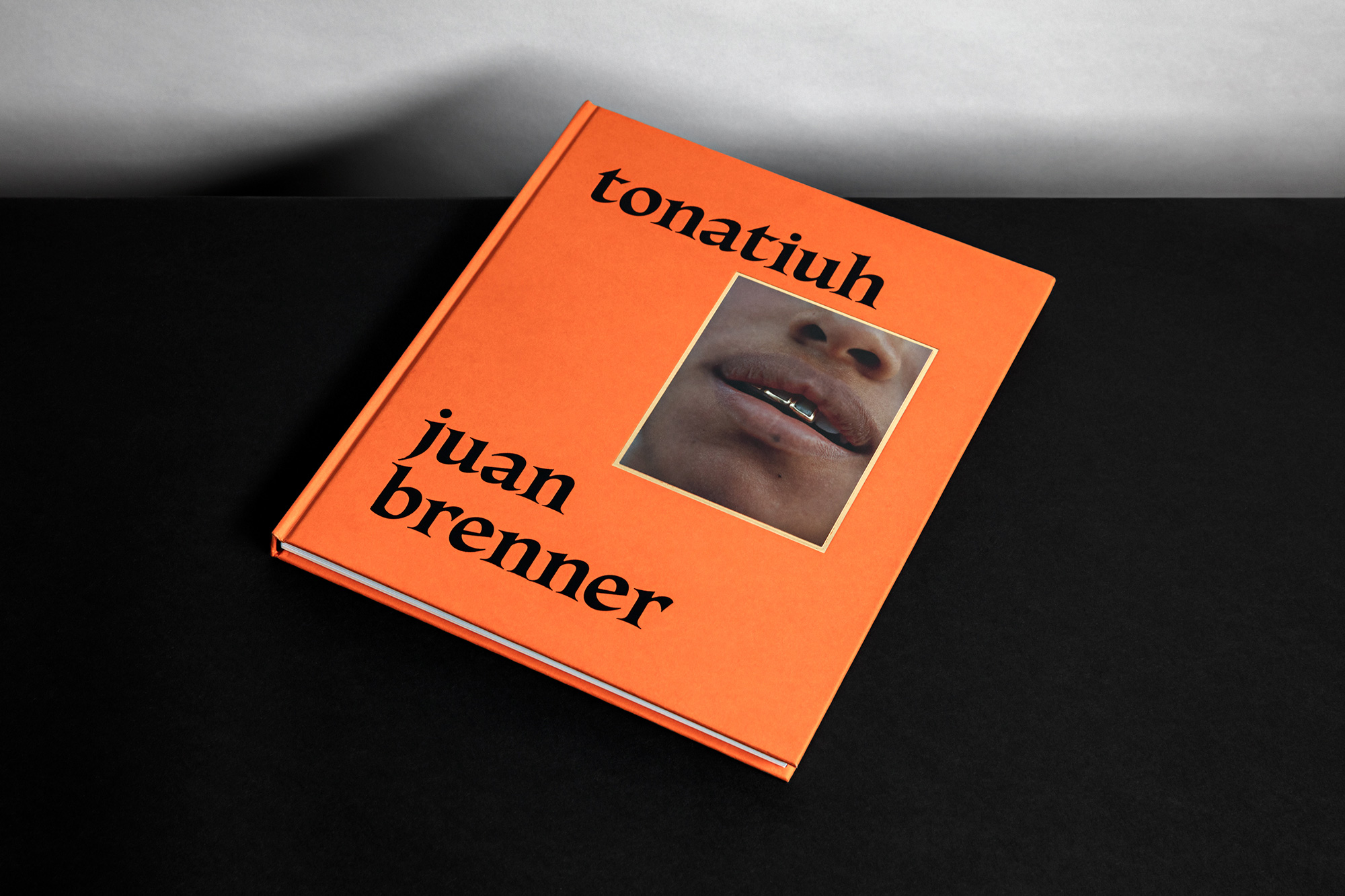

In Tonatiuh (Editorial RM, 2019), Juan Brenner takes account of his native Guatemala and photographs the scars of its generational pain. Throughout the book, and after a decade-long career as a fashion photographer in New York, Brenner tours his homeland through travels that bring him closer to his ancestral roots. He finds tensions between indigenous and imported culture and discovers subtle and overt signs of social trauma. His pictures are lyrical and tightly focused with symbolism and metaphors that, when strung together in his sequence, sum to verses of a melancholic hero’s journey. Tonatiuh is both a portrait of contemporary Guatemala and a reflection of the artists’ search for identity in a land and culture he left long ago, only to later return as a different person entirely.

Tonatiuh is short-listed for the Paris Photo/Aperture First Book Prize and will launch 8 November at Paris Photo.

I’ve been feeling out of place for so long, so out of place that I didn’t feel worthy of exploring topics of race, social reality and inequality. I started this project with a lot of fear and insecurities, how was I going to talk about stuff I’ve been so far away from?

Could you talk about the origins of Tonatiuh and how you got started with the project?

The project had its genesis in 2015. While travelling through South America (Peru and Ecuador), I had glimpses of indigenous power, equality, and unity that made me put in perspective the reality and current situation of Guatemala’s most affected population.

At the same time, I felt a cycle was about to finish in my life, and I felt the need of searching deep inside; I knew I had to work on themes I’d previously avoided. My origins, my country and the history of how things have happened in Guatemala is something I ran away from many years ago. I suddenly decided that it wasn’t something I wanted to deal with and just left it behind; both geographically and psychologically.

After some investigation and a lot of thinking, I decided that the topic of “Indigenous Power” was not something that applied to my context and that I had to look to the past. I had to search for the most elemental and simple idea to try to explain the way we got here. So, I chose the moment of the Spanish conquest as the detonating idea of my project, and the figure of Pedro de Alvarado as the human incarnation of power, thirst, ambition and ruthless attitude against the new world, all of which are behaviours that still affect our society 500 years after it happened.

I’m curious to hear more about your travels through Peru and Ecuador; was there a moment of realization for you that shifted your perspective on your own country’s identity and, in turn, your own? And how do you think your sense of self and community has been shaped by the echoes of Guatemala’s colonialist period? In some sense, Tonatiuh feels almost as much like an inward journey of discovery as it does an insider’s perspective on history and culture.

Travelling through those countries is surreal, you find yourself in cities with more than a million inhabitants, 95% of them of indigenous descent, that for a Guatemalan is very weird, you know? I mean our country is almost 70% of indigenous origin but the idea of power has never reflected that reality. When you feel that indigenous power and see the way their social dynamics work, it’s impossible not to feel you deserve the same, it’s very hard not to think it could happen in your land.

In the beginning, my project was going to revolve around powerful towns and important indigenous figures in the Maya descendant highlands. I started doing some investigation in the history of Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, all three countries with similar stories and realities of racism, conquest and inequality. In talking to people and trying to find my way around this reality, I spoke to a very talented Ecuadorian anthropologist and exposed my fascination and appreciation for how the indigenous reality works in the South American highlands. To my surprise, his position was a very incendiary one. He destroyed my idea of their power and explained to me how indigenous people will always have the power that “the white man” allowed.

Did your conversation with that anthropologist spur a sort of epiphany you had about your own identity and upbringing? A moment when you started to think about yourself differently through all of this? In hearing about your research and travels, it sounds like there were many layers you needed to unfold before you found the core of what this project became.

That conversation ruined my initial idea, haha. It was really shocking to accept that I was so wrong and confused; when it comes to identity it’s a matter of gut feeling, you know? I’ve been feeling out of place for so long, so out of place that I didn’t feel worthy of exploring topics of race, social reality and inequality. I started this project with a lot of fear and insecurity. How was I going to talk about stuff I’ve been so far away from? Who do I think I am to grab a camera and try to explain a reality I could never start to grasp? I mean, I’m by no means rich but yes, I do feel privileged. I went to school, I speak English, and have travelled the world; it’s such a different reality from the people in the highlands, very intense and precarious. The most basic things, stuff that “we” take for granted become so scarce and hard to get once you’re there.

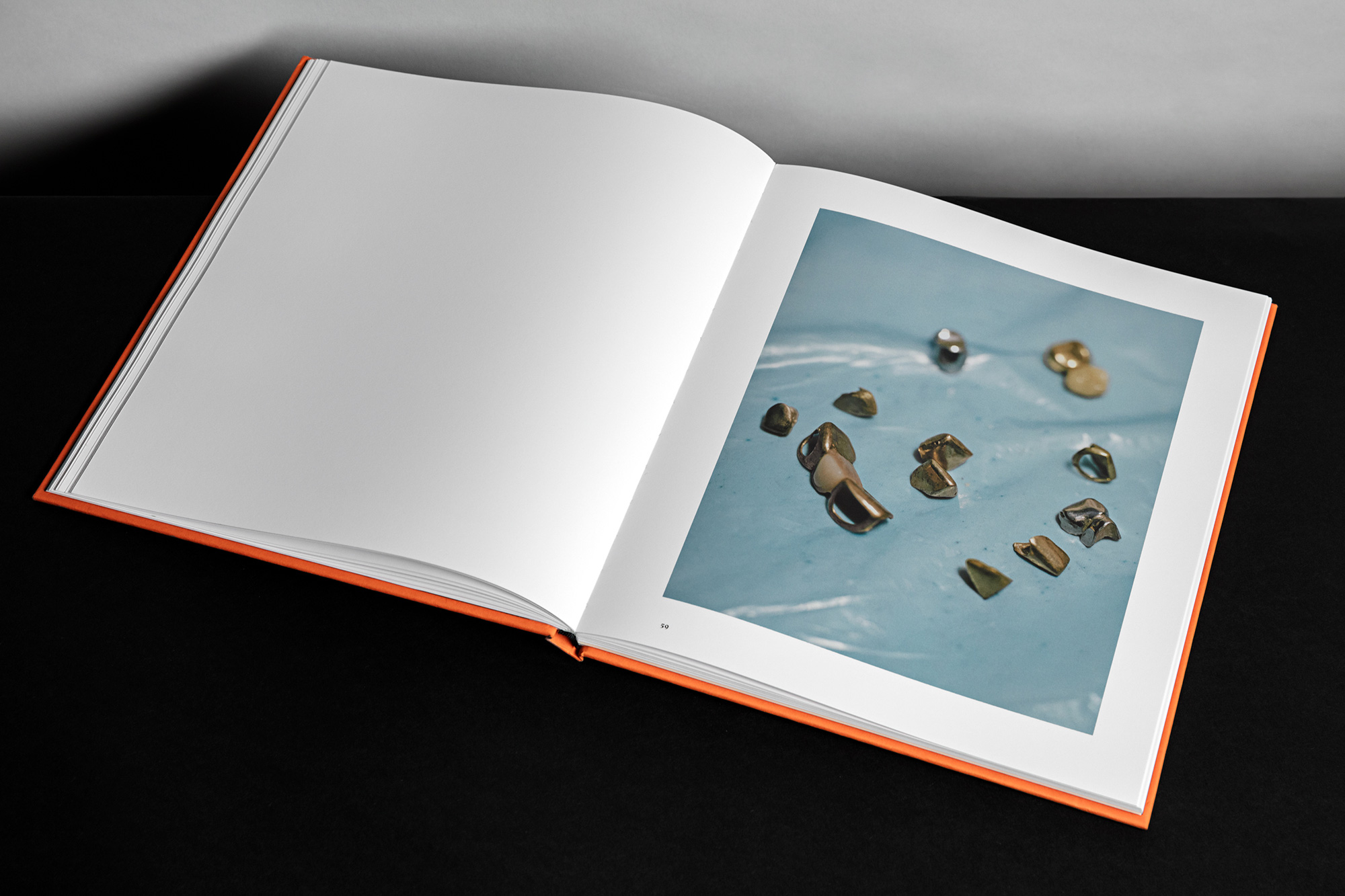

I did have an epiphany though, but it was on my third trip (I did 12). After I decided Pedro de Alvarado was going to be the main figure on my project, I started looking for gold chains and rings. I was intent on getting images of that; I needed gold. Gold became really important in the project as Alvarado was so intense about getting it. He came here by mistake thinking there were huge amounts of gold like in Peru and Mexico; however there was none. So, the moment when I shot the first “gold-teeth” portrait, that’s where my vision became solid and I understood how I had to proceed.

There is an Odysseian quality to your narrative that I admire. Rather than telling the story of a Greek King’s journey home, you’re placing me into the shoes of a 16th-century Spanish conquistador scouring modern-day Guatemala for wealth. With you as our guide, we survey the land and measure its people. While some of the pictures in your sequence do portray small evidence of gold (teeth, jewellery, trophies), more of the pictures illustrate dead flowers, broken glass, and mud-cracked skin. There’s poverty you’re showing us, but maybe it’s more of a spiritual poverty that you’ve found in your journeys. Is this accurate to say?

Perhaps, unconsciously, I was looking for gold myself. I like what you say about poverty, the whole project started with trying to stay away from that, but the spiritual aspect of the question is what intrigues me the most. In general, people in the highlands are broken in so many ways. The territory has been “beaten” for more than 500 years, between rival tribes before the conquest war, then the Spanish invasion. After that, slavery and colonization for more than 400 years. In the twentieth century, the highlands were the most affected areas during the Guatemalan internal armed conflict (that lasted more than 35 years). In 1977 a massive earthquake destroyed more than 80% of the infrastructure in the area. Today, massive immigration to the US and drug trafficking are main players in the under-development of those towns.

Aesthetically, I was very into the idea of showing the “B-sides” of Guatemala. I knew there were many images I was going to find, scenes I had constructed in my mind, and I found them! But there are also so many situations that are extremely weird and make no sense, but that is our reality.

What I think struck me most about the project is the measure of intimacy that your pictures speak to. Your portraits specifically are respectful of your subjects. While the book is entirely melancholic, it never alienates. And you’re forging a sort of sympathy for your subjects because of that. The project is incredibly tender even while it functions as a record of trauma. Have you received much of a response to the work in Guatemala itself? I know the project is beginning to make its rounds to a global audience, but how do you hope the work is received by those who understand and feel these colonialist ghosts in their day-to-day lives? And those who can’t simply close the book and consider the story complete?

That is still to be discovered as the book launches during Paris Photo. From the beginning, I knew 3 things: first of all, I knew I wanted to create images that spoke to me personally, I knew this was my chance to find myself in places I’ve never been to. Secondly, I knew I wanted to make a book, I felt like the only way to create a narrative this complex would be on a body of work contained between paper and ink; that dynamic was perfect for what I needed to say. And lastly, I knew this was a project that was going to “work” outside Guatemala first; I knew the work was going to resonate in the First World first and it was going to trickle down here. Our society (Guatemala) is so used to “the problem” and at some level, we became psychologically bulletproof to those images, it became a part of our collective unconscious.

The book is published in English by a Spanish editorial house. It’s a statement that definitely will get me in trouble here, but I kind of want that. I want people to question anything they want about the way I executed this project, that will only make it grow and evolve into what it needs to be.

Gold became really important in the project as Alvarado was so intense about getting it. He came here by mistake thinking there were huge amounts of gold here like in Peru and Mexico. There was none.

I think that one of photography’s limitations is that it can speak to what is in front of the camera’s lens—what’s there—but has more difficulty envisioning possibilities of what could be. I think much of what your work strives for is to look at wounds of Guatemalan society and start to assess how they may be healed. I wonder if you see a pathway for a sort of healing and historical reconciliation to take place. Are you hopeful for Guatemala’s future, or are you anxious about what it may bring?

That’s the most sombre aspect of the project, I’m sincerely not pretending my work can change anything, or even put a “call to action” out there. I just wanted to grab all these ideas that could create a narrative, a survey of the actual situation in the highlands. Like I mentioned before, we’re so used to the situation and used to looking away, I needed to document and find those images and put them in people’s faces, just as a reminder, as evidence.

I believe my role in this situation ends with a closed /plastic-wrapped book. I did this for me, I needed to grow and leave a bunch of insecurities behind. I’m a better person after I finished editing the book and I hope people find at least one image that sparks the same hunger for understanding our history and origins as it did for me.

Guatemala is about to confront its hardest cycle, no doubt. The future looks sombre. The whole region is on fire as we speak, chaos and general unrest is our reality. I don’t see that changing anytime soon.