Interview: Paul Thulin

Ode to Irving

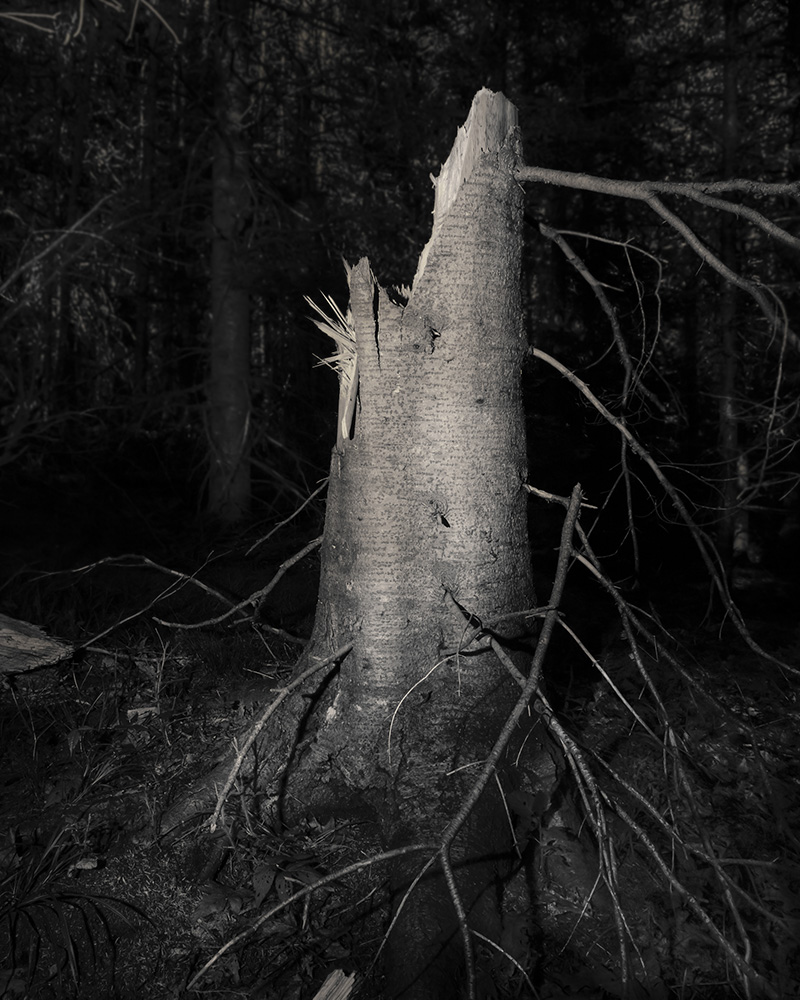

Using the dense backwoods of costal Maine as a backdrop, Paul Thulin takes us on a journey that unfolds the secret layers of his own family history and personal identity. His series Pine Tree Ballads reads as a poetic vision, weaving together historical record and interpretive imagery that are inspired by a century of past-down stories and ominous childhood memories.

Because of its resemblance to his homeland of Sweden the artist’s great-grandfather settled on the North Atlantic coastline. In this landscape the family clan embraced their past, as well as their evolving present and established their own story through myth and imagination. As the artist states, ‘In this place, stories have arisen from the mouths of both the young and old that over time have become the essence of my family’s identity.’ And it is here, in this work that we are given a haunting glimpse into the shared history and dream-like world created not only by the artist, but also by his ancestral traditions.

Antone Dolezal: Your series Pine Tree Ballads is a journey into family history, cultural identity and childhood memory. Would you expand upon how you came to begin this project and how it developed over the years?

“The truth is always something that is told, not something that is known. If there were no speaking or writing, there would be no truth about anything. There would only be what is.”

— Susan Sontag, The Benefactor

Paul Thulin: Originally, I was simply shooting all of the time with all kinds of cameras, film, etc. during the summer months with my family on a farm off the coast of Maine. I was following the footsteps of my grandfather who took lots of images of the family for homemade photo albums documenting not only leisure, but more often than not, the labor of every summer. Those photo albums are kept in an old clamming basket in a closet at the farmhouse and date back to 1917. As a kid, I would obsessively look them over and memorized each album to a point that they became an inherited and unquestioned narrative in my mind regarding the people, landmarks, and events that took place before I was born. Family photo albums are spiritual objects especially when they present the history of a particular family in a very specify landscape. The images in the photo albums are worn from viewing with scribbled captions that vary in clarity depending on the year and my grandfather’s declining penmanship. Over the years many family members and visitors have looked at these albums, touching the photographs, and telling stories.

The albums materially consist of B/W prints spanning several decades to post 70’s color images including all types of photo paper from exotic early Kodak papers to 1-hour lab varieties. In some albums, a few anomalous images and formats (e.g SX 70 Polaroids) stand out: obvious ‘guest’ images sent from family friends that had visited during the summer. The albums are records of family, but are also an archive of the physical character of vernacular photography from 1913 -1991. My memory of the farm is heavily influenced by the evolution of the materiality of photographs themselves. Marshall McCluhan might say “The medium is my memory is my message.” Joking, but my point is that photography has a very powerful relationship with the nature of one’s immediate perception and memory. My experiences and memories of family, farm, and landscape is an amalgamation of the photographic representations in my grandfather’s photo archive, my personal production of Pine Tree Ballads, and an unmediated engagement of the events and actions of the everyday. This blending of impressions and filtering of life restructures the real in such a way that it is no longer, as Jean Mitry, French film theorist, states “objective and immediate.”

Roland Barthes’ thoughts about the nature of photography have me thinking about one’s sense of place being established by the coexistence of images and actual. What once was, still is and simultaneously is not, and will be until the image or the actual erodes from time or we stop looking and/or engaging. Confusing but I think this is the premise for the story of history. My experience of the farm is wrapped in an immense sense of aura that surrounds the worn, treasured photos, but is also sensed from personally exploring the landscape that was and is the subject matter of the images…enduring but evolving. The rocks, trees, roads, sheds, and tools experienced in the present day stand as relics and landmarks of prior generations but also exist as props for a continuous family reality. In a way, the images gave me a sense of “place” that was sacred and filled with nostalgia far before I had truly physically and emotionally interacted with the land on my own. My family’s identity is a living memory echoing and transforming the fixed past of the photo albums with the perpetual slip of the present becoming the unfixed past, life unfolding, or, in some cases, my fixed images.

To answer your question more directly and honestly, I was simply documenting mundane events and one day I awoke and decided I was working on a sequence named Pine Tree Ballads. I do remember that at some point I came to the realization that images of family become deeply profound and meaningful as time passes. Up until that realization, I never thought family should be the source of one’s artistic practice, because it seemed to be too available to be serious subject matter; however, I considered my images as a unique family story intended to be authored for the looking/reading of future generations. Pine Tree Ballads is my folktale, my emotional, spiritual, rational, and experimental “documentation” of family, place, and time; it is my version of the truth.

In our past conversations you spoke on how specific stories about your great-grandfather’s settlement to coastal Maine seemed larger than life…. almost as if the stories were centuries-old fables. I’m curious to know how your perception of these stories shaped this work and if you could elaborate on how and why folklore became an important component to constructing this series?

The stories have influenced this series immensely because they made the farm seem animated, ancient, and inhabited by ancestral souls. For example, there was an old, built-in, white-washed birch wood ladder that accessed a storage attic above the mud room that was so weathered that the wood literally looked like scratches on a negative. I say “was” because the farmhouse was renovated in 2014 which is a new era for Pine Tree Ballads that will be addressed in the future. Anyway, it was a rickety old ladder that always made one extremely nervous when you climbed up it to get clamming gear or a life vest. Antique hand-painted signs and scribbled notes were nailed all over it warning of potential disaster if you missed your step. It was a generational timeline of cautionary script that charged the present moment with history and an intense sense of self-awareness.

My grandfather often anecdotally described how Captain Hutchins froze to death at the bottom of this ladder one winter when he accidentally fell and broke his leg. He was a retired cook that served on whaling ships and supposedly had a wooden leg from a boating accident. He lived in the farmhouse alone for years before my great grandfather took ownership of the property. As a kid, grandfather heard Captain Hutchins tell many a story in which the old sailor always single-handedly saved a whaling expedition from a disastrous ending.

As you can imagine, the thought of Captain Hutchins freezing to death with one broken leg and one wooden leg in a room with an ominous ladder that you use everyday does make the imagination run wild. At night, I often think I can hear his wood leg dragging on the worn floors of the mudroom or imagine the howling wind as his enduring last breath of life. I am never scared, but always feel a connection and maybe a bit of warning that the place we call a summer home has an epic and rugged history. It is important to point out that fear or sense of haunting is not something I generally associate with the landscape or the mood of Pine Tree Ballads but rather a general sense of uncanny wonderment that inspires stories, ballads, and poetry. Coincidentally, the first image I ever made that I considered a fine-art print was of this peculiar staircase. The image was very Walker Evanesque but if I could photograph the space now it would be an entirely different style that would vibe with the unsettling wonder of the occurrence described in the story. I would treat the staircase and mudroom more as relic than reality.

Folklore is in essence the tradition of history shared amongst a region, tribe, or in my case a family. The history and identity of a family thrives on stories of the past, an awareness of sharing knowledge, and the privilege of participating and contributing to a mythology interweaving past and present. I see the orchard farm, the shore, the pine trees, the granite, the muck, the gusting winds as natural elements and the symbolic essence of my family narrative. To understand the family, you need to know the folklore, the tradition, the story of a photographic moment in the context of a particular shared history of looking rather than attempting an unbiased, neutral examination of a document depicting a subject in a moment in time.

When you sit with a family album or experience an old fashioned slideshow, you anticipate an active dialogue that provides context for the images. In the digital era, this type of testimonial experience is diminishing in favour of a steady production stream of capture, transmission, and quick “thumbs up/ heart/like” reception encouraged in mobile phone cameras, apps and social media platforms. I am doubtful that modern day families revisit snapshots and ceremonial pics on iPhones, digital image archives, etc. in any comparable fashion to the intimate bonding and identity building rituals of looking, formalised presentation, communal spectatorship, and collective story invention shared amongst generations during the analogue era of family albums and/or slide projector shows. Maybe it is too early to tell or pass judgment, and someday my great-grandchildren will look to a new media for family engagement of a digital image/texting archive.

Shack of Ryhope Wood

Grave of Abelard

You’ve also talked about how the stories you were told growing up ‘fuelled your imagination and had the power to transform floorboard creaks and shadows into enduring ancestral ghosts of the past.’ Could you tell us a bit about how the images in this series came to life from these stories and maybe give us an example of a specific image that was created from these memories?

Lets look at Cervantes’ Shadow and Shack of Ryhope Wood. Both of these images are inspired by another family legend surrounding Captain Hutchins. One of the storage sheds on the farm had an active beehive inside that was causing quite a stir amongst the families on Gray’s Point (island location of the farm). Several of the families had fishing and sailing equipment in the shed and the hive was causing havoc anytime someone attempted to enter. Several failed attempts had been made to remove the beehive when word of its existence caught the ear of our fearless Captain Hutchins. It is said he took the challenge without hesitation. He covered his head, grabbed a remnant of a sail canvas and a rolled up a Farmer’s Almanac, and then proceeded to enter the shed, close the door behind him, and unleash a Down Eastern beating upon the pesky insects. A memorable composition arose from the shed consisting of thumps, banging, and the loose tongue of a pissed off sailor. Minutes later the old cook with a wooden leg emerged in the doorway with a sly smile and a buzzing canvas tarp. My grandfather claimed he witnessed the entire event.

Now, I have my doubts things happened this way but the story does make you look at strange looking men and sheds in a new way. The average man becomes a hero worthy of adventure and the shed in the woods becomes an inaccessible space that houses unseen threats and magical moments. I think Cervantes’ Shadow and Shack of Ryhope Wood relate a sense of the valiance, mystery, absurdity, and humor all brewing from this family story.

The landscapes in this series are very haunting, and it seems that being in the woods at night became a recurring theme in this work. So much of being a kid and going into the woods after dark is about surrendering to your own fears and seeking out the mysterious and unknown. I can only assume this work is a little about recreating your past while also exploring your present relationship to this space and your own immediate family… what is it that makes these themes so important to you and your work?

When I was a kid, we used to camp in a cabin at the end of Gray’s Point about 1/2 mile away from the main farmhouse. At the time, the farmhouse was the residence of my grandparents, so my parents and I would kind of rough it at the Van Wyke cabin all summer with no electricity or running water. It was amazing and something I wish my kids could experience. Sometimes we would visit my grandparents for dinner and walk back to the cabin late at night. Often it was so dark that you could only see a few feet in front of you with a flashlight. My father would sometimes turn off the flashlight to freak us out. It was isolating and caused immediate panic, but at the same time you were in awe of the stars in the night sky, which gave you a sublime sense of union with the grand expanse of the universe. My father would joke that a “real man” could walk from the farmhouse to the end of the point without a flashlight. Well, when I was a teenager I took the challenge. It was a hike I will never forget and has inspired much of the series in regards to balancing themes of isolation, mystery, wonder, the miraculous, and terror. In my opinion, everyone needs to face a symbolic darkness and/or pilgrimage in their life that tests their mental and physical boundaries in order to face a part of themselves that has no choice but to meet the unknown, the unexpected. This is how one learns to expose their perceived limitations and find the courage to overcome them. You either hide in the dark or learn to see and become part of it. This is an ancient symbolic space of absence found in many mythological journeys like Buddha’s Bodhi Tree, Christ’s Desert, Luke Skywalker’s time on Dagobah, and Crusoe’s island. As a photographer, the night poses all kinds of challenges as does an artist facing the complexity of himself, his family and their history.

Pine Tree Ballads seems to be a departure from your past projects. This series is dedicated to composing a visual narrative that is very much rooted in storytelling and magic-realism. How did you become engaged in working this way and how has it changed your image-making process?

I am not sure this is completely accurate as a few other of my past series have definitely engaged narrative and storytelling. I think it gets kinda of confusing because I actually have a lot of work that looks quite different and explores a variety of styles and genre in photography. I think Pine Tree Ballads raises the bar in the complexity of the storytelling and is much more developed in regards to implying a subtext for a viewer to discover. The titles of the series are a good example of my proclivity to complicate the narrative structuring of the sequence in hopes of challenging typical conventions of narrative, character, and plot.

Most of the time, a viewer engaging a photographic sequence for the first time within a book, on a gallery wall, or website pays little to no attention to the titles of each image. Titles are often disregarded as a secondary element in photography that only serves the purpose of stating conditional fact, identification, and/or exposing romantic notions of subject. Classic photographers have typically been quite dismissing of text often claiming that if the image does not say what you want then it has failed. For Pine Tree Ballads, I consciously put effort into having titles that produce a subtext of relations between the imagery and the personal, literary, philosophical and historical sources that inspired their creation. This intentionality makes the images and the text quite dependent on each other narratively in a way that the image could never quite do so on its own. The titles encourage a second reading that often provides a new conceptual framework to give the image a new narrative foundation.

For example, the title Cervantes’ Shadow provides the subject of the image wearing a bucket on his head an association with the author of the novel, Don Quixote. The novel has a psychologically complex protagonist, Alonso Quixano, that can be simply described as a well-read, rational, middle-aged, chivalrous madman. Cervantes’ Shadow’s association with Don Quixote moves the portrayal of the lone, armed figure in the woods away from the classic horror characterization found in a protagonist like Jason from the Friday the 13th movie franchise or a backwoods hillbilly character from James Dickey’s novel Deliverance. I think this is important because a viewer might simply fall prey to a horror association which would be a gross oversimplification of the narrative intent of the image within the sequence. The character and the scene are a hybrid of horror, heroism, play, and delusion. The title enables the reader to become aware of the slippery, ambiguous intention of the characterization of the scene which oscillates between reality and fantasy, buffoonery and threat.

The image title, Shack of Ryhope Wood, is a literary reference to Mythago Wood by author Robert Holdstock, a 1984 bestselling fantasy novel I read as a teenager. In the novel, Ryhope Wood is an ancient forest, a parallel universe that has a slower rate of time than the outside world and is inhabited by animals, monsters, and humans generated from the memories and myths within the subconscious of nearby humans. This title encourages the reader upon discovery of the literary source to reimagine the shack in the woods as a mysterious place in space and time that is psychically charged within by those outside of it. The title is intended to complicate the image by unconventionally attaching associated narratives to it. One has to read the image as part of a much larger sequence of plots and ideas than purely images.

Does a viewer actually get all of this from the image titles? I am not sure, but I feel I have planted the seeds that can lead to some interesting associations and relations. This is really all I can take responsibility for as the author of the work…there is a logic to the structure of the “text” that undermines a single reading. Pine Tree Ballads has changed my artistic goals in that what is important to me in a work now consists of two equal interests —materiality and literary complexity. I feel I am as much an author as I am an artist. This series is a narrative driven, photographic and textually inspired work that serves as a docu-literary interpretation of my family identity in relation to a specific landscape in Maine, a collection of photo albums and oral histories, physical landmarks, and cultural influences.

Memoriam – She Walks With Her Shawl

There is also a lot of technical experimentation and different styles of photography present in Pine Tree Ballads. Why is it important for you to mix more traditional styles of the medium alongside the more unique processes seen in the series?

The first edit of Pine Tree Ballads happened about 5 years ago and looked nothing like it does today. Most of the images were straight documentary inspired by photographers exploring family, such as Jessica Todd Harper, Doug Dubois, and Sally Mann. I was looking to document the everyday relations, but mixed with a cinematic and painterly quality of light, a common trope modern day romanticism we all know too well. At some point, I realised that in addition to these images I had all these amazing, formally complex, “bad exposures/scans” in a variety of different formats captured both digitally and on film that just did not fit stylistically. The images looked unique so I was curious if I could make something out of them that celebrated their flaws as an attempt to redefine “straight photography.”

At this point in my life, I was growing mentally exhausted and artistically numbed by the perfect negative/print, large format photo worshiping I had always felt pressure to achieve from the generation of professors that taught me. They seemed of a different era that was equating mastery to technical and chemical consistency and control that removed any indication of the photographic process. It took photography so long to conquer the chemical and technical struggle to achieve high-fidelity photographic representation that many practitioners censored what I find to be the material profundity of the medium. It is liberating to allow the medium to simultaneously adopt the utopic, immersion of large format image fidelity supported in traditional “straight photography’” while also aesthetically and formally appreciating evidence of photographic processes.

The straight aesthetic made Pine Tree Ballads seem flat and generic so I decided to interject a dream sequence into the series that would adopt what I like to call the “aura aesthetic.” The images would celebrate the scratched, touched, rubbed, and overexposed as a gateway into a “document” dream world that would unbalance the straight aesthetic by highlighting photography’s material essence. The idea and power of “aura” is obviously something I derived from Walter Benjamin, who states that aura is an object’s “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” and “…a strange weave of space and time: the unique appearance or semblance of distance, no matter how close it may be.” The photographs in our family albums have this sense of aura. One can detect generational history of contemplation and preservation that adds emotional weight to the ritual of looking, basically empowering the photographs as unique objects in the flow of time and culture.

The images that make up the latest version of Pine Tree Ballads I feel have a similar sense of aura. There is a crisis of the photograph being presented both as an object looked at, transported, stored, and destroyed while at the same time there is the narrative and/or cultural significance of the subject of the photographic event and sequencing existing in the past as well as the present. Is it real or reproduced? What was this then and what is it now? Am I looking at history or a story for the present, or both? Is the main subject of the work, the photographic object or the often obscured photographic representation? Before I knew it, the “aura aesthetic” of the dream sequence experiment dominated my creative thinking so I abandoned the original “straight photography” aesthetic and the Pine Tree Ballads of today was born.

Adopting the “aura aesthetic” really changed my editing and shooting process. I look to all of my image archive regardless of its origin or state of preservation and find amazing images that would have otherwise been ignored. I have become obsessed with photographic material disruptions, such as poor development, lens distortion, loss of color, grain coarseness, mold, and the multitude of ways paper stains, rips, and deteriorates over time. To this day, it is difficult for me to remember how images were originally captured and whether or not the flaws of the image are “real” or simulated with software and scans. It does not matter to me as long as the physical prints are firmly entrenched in the material possibilities and limits of analogue photography. I want to create an authentic sense of aura which differentiates itself from trendy insta-art nostalgia fueled by Instagram filters and smart phone apps. I believe the analogue essence and “aura” sensibility of Pine Tree Ballads is directly related to years of looking at those well loved family albums.

My investigation into aura has become a peeling onion of sorts that has really caught my attention in regards to artistic possibility. Recently, I have actually been physically cracking the glass on the frames of my prints. This brings a whole new haptic auratic event to the printed works as the ragged, 3 dimensional cracks challenge the metaphysical nature of the 2-dimensional, flattened, analogue negative marks of exposure and surface deterioration.

For me, this work is reminiscent of themes seen in literature and folkloric storytelling. I’m interested to hear if this was something you were initially inspired by and what other mediums or artists you were looking at when making this work?

The themes and ideas Pine Tree Ballads explores are derived from a variety of sources of inspiration. I borrow from and am influenced greatly by literature and poetry, Buddhism, Voodoo and Catholicism; Nordic, Greek, Native American and Spanish mythology; eastern woodblock prints/scrolls, Northeast American painters, and Japanese photographers; fantasy novels and video games, and, most importantly, the childhood imaginings of my daughter.

I believe family identity and the character of a specific landscape, a sense of place, is influenced by a wide variety of folkloric, cultural, literary, and personal influences. My goal is to constantly play these off each other and complicate Pine Tree Ballads as a photographic sequence that inspires a reader to decode the “text” multiple times through multiple readings.

Throwing out names influencing the series is a fun exercise but an almost endless task:

Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Frost’s poem “Directive,” Sharon Olds, Matt Rasmussen’s poetry book Black Aperture, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Buddha, The Journals Of Lewis And Clark, Thomas Merton, The Bible (Old Testament), William Blake “The Proverbs of Hell,” The Legend of Zelda video game, Shigeru Miyamoto’s narrative inventiveness, Terry Brooks’ fantasy novels, Alec Soth’s Broken Manual, Nirvana’s unplugged, haunting rendition of Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World,” Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood, Mathew Brady’s deteriorating glass plates, Michel Gondry’s dreams becoming films, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Nine Inch Nails, David Foster Wallace’s footnotes, Umberto Eco’s originality, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Homer (of The Odyssey not Simpson), Andrew Wyeth, Keith Carter, White Stripes “Icky Thump,” Krilanovich’s novel The Orange Eats Creeps, Sally Mann, musician Beck for challenging convention, Dario Robleto’s sympathetic magic, Trenton Doyle Hancock’s characterization, Jane Addiction’s live remake of “Sympathy of the Devil,” William Kentridge’s sense of movement, Thomas Barrow’s Cancellations, Daido Moriyama, Takashi Homma’s First, Jay Comes, Rinko Kawauchi’s mastery of sequence and blown highlights in Illuminance, the emotional mood Masahisa Fukase’s The Solitude of Ravens , Bill Morrison’s film Decasia, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, CS Lewis, JRR Tolkien, Mark Twain, the material and conceptual experimentation of Paul Graham’s American Night, Paul Nougé, Monet’s atmosphere, Guillermo del Toro’s dreams, Cormac McCarthy’s novels The Road and Blood Meridian , the wonder and mystery of Mars Rover Opportunity’s first transmitted images, Sharon Harper’s universe, Seba Kurtis’ material phenomenology, Godspeed You Black Emperor’s emotional degradation and suspense, Chris McCaw’s sun-burned physical prints, Juergen Teller’s technical spontaneity and his book The Keys to the House, Robert Frank’s formal unbalance, Chris Verene’s enduring family story, Annie Dillard’s micro details of natural phenomena, Charles Darwin’s repressed sexuality, Joshua Lutz’s courage in Hesistating Beauty, Yi-Fu Tuan, the overlooked but powerful photobook Xavier Zimbardo’s Monks of Dust, Thorsten Brinkman’s humor, and many more

Valley of Tunguska

You already have had a few solo shows of this work and in the exhibitions you take a multi-media approach when working in a gallery space. How does this enhance the viewer-experience and what are your goals for developing it in the future?

I have actually only had one multimedia solo exhibition of the series entitled Pine Tree Ballads:Labor Omnia. In the exhibition, I wanted to explore the narrative possibilities of an immersive, multi-sensory, aesthetic experience that is based on a photographic sequence that I treat as being in a constant state of “situational flux.” I find it refreshing to explore a broad range of media including photography, video, audio, performance, sculpture, and olfactory experiences to transform an exhibition space into a multimedia storytelling event. My desire is to push beyond the simple display and reading of “classic photographs” towards a new type of docu-literary inspired exhibition that challenges photographic conventions and questions the nature of the act of looking.

For instance, I recreated the image Plaster Bat as an actual plaster wall at the end of a photo lined hall that was lit by a nightlight. The hall had a 100 year old wood floor installed that was purposely left “spongy” to unbalance the viewer. The floor was also sprayed with the aroma of black pepper. I was interested in creating a multi-sensorial situation that put the audience in a particular state of mind when viewing the images. I also wanted to keep Pine Tree Ballads from ever being a fixed work of art. In my opinion, it is less about it being a single, definitive, collection of images and more about considering how one tells a story in a nuanced manner at a particular point in time. Plaster Bat is simultaneously an image, a physical plaster reproduction of a farmhouse bedroom wall, and an actual bedroom wall with a strangely familiar, plaster repair job that takes flight in low light. I mentioned “situational flux” which means that my methodological approach to photography, art making, and storytelling in general is that no work is ever finished or needs to remain static. The overall aesthetic and emotional tone of the work should have definable boundaries but other than that anything goes. An example of this is when I edition images, I do not specify size or whether or not the image will be in color or b/w. I decided long ago that I will not play by the standard rules when it comes to telling my story. As long as the audience finds intellectually stimulating substance and emotional resonance, I am satisfied and prepared to take risks .

In the far future, I would like to get to a point in my work where I could install an iteration of Pine Tree Ballads deep in the woods of Maine far removed from audience. The exhibition would simply consist of a murder of crows feeding on a bed of antique glass evil eyes. Only one “viewer” at a time would be given a map to the location and one of my grandfather’s cameras. The work would always start in the middle of night … and maybe I would give them a flashlight.

Exposed Fog, She Whispered

Whistler’s Daughter

Plaster Bat

Cervantes’ Shadow

The Revealing Arm Redux