Interview – Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: One Wall a Web

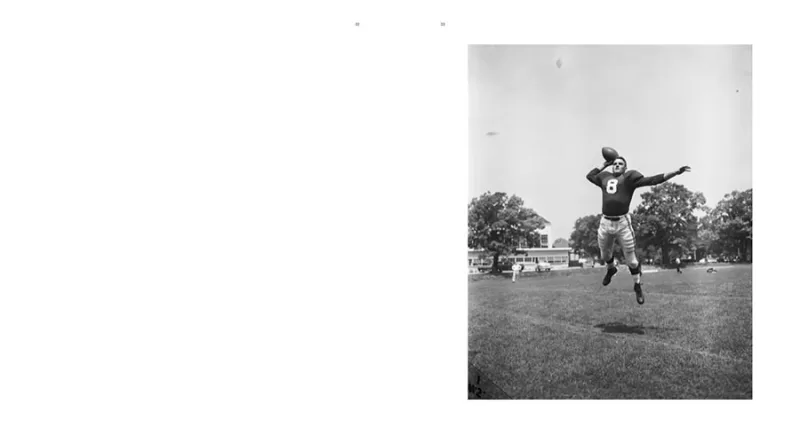

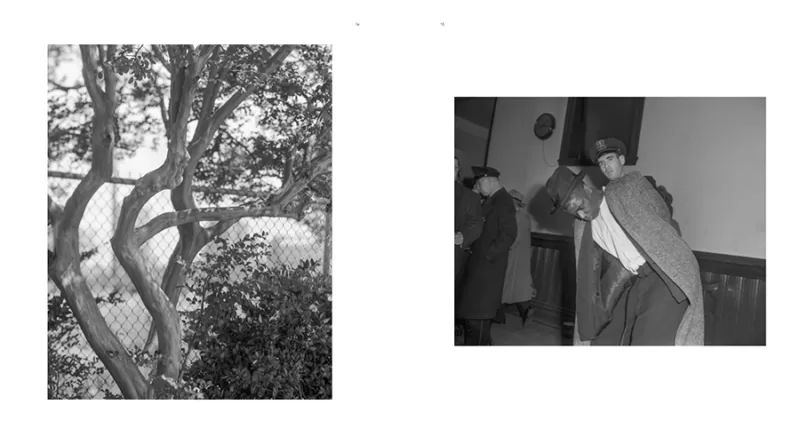

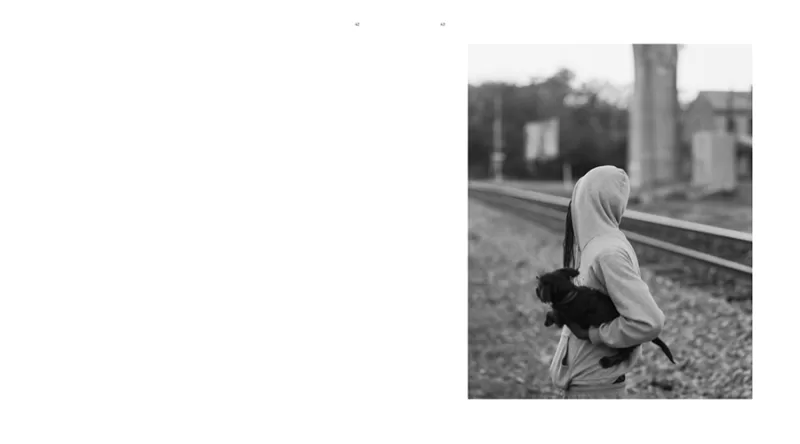

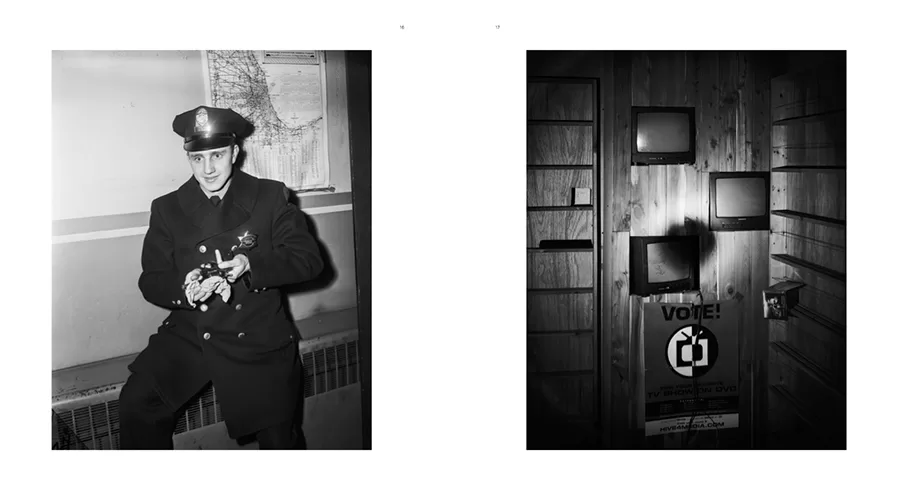

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s One Wall a Web is an exhibition that gathers work from two discrete photographic series that he made in the United States, Our Present Invention (2012-2014) and All My Gone Life (2014-2016). The resulting show at Light Work and accompanying issue of Contact Sheet comprise two distinct strands of photographs: the first, a series of appropriated archival 4×5” negatives; the second, a series of original photographs. Wolukau-Wanambwa says of this exhibition that it “attempts to address the normalcy of fear, separateness, and violence in a moment suffused by them, but also in a culture riven by the habitually limited prescriptions of images.”

I always like to ask other artists how things started… For you, how did you get interested in images? What were the influences and ideas that compelled you to work photographically?

I honestly don’t remember, but it must have been when I was very very young. Images have always been an active part of my life, in both the visual and verbal sense of the word. I can say that I picked up a camera for the first time with the intention of going out into the world and making photographs with a capital “P” after getting seriously interested in film, and that burgeoning interest was tremendously affected by my subsequent discovery of the work of the first generation of Magnum photographers in my late teens and early twenties.

As a photographer you are in some ways still channelling a “documentary” practice, but you work in multiple modes of image-making and collecting. Can you tell me a bit about the impetus for each of the two bodies of work that make One Wall a Web, and the idea to bring them together?

I’ve never felt the urge to disavow the term “documentary,” or to position my work in some other terrain or mode. I consider the work across both series in all its forms to be documentary photographic work. I think that the way in which the term “documentary”—and its associated meanings—has been sequestered into a narrow and disingenuous relationship with “reality” is not a reason to abandon it, but an imperative to reclaim it in all its myriad complexities. So I’ve never felt myself to be at war with either the documentary mode or its traditional canon. In many ways, I think the work in both Our Present Invention and All My Gone Life reflects a slow process of working out the influence of someone like Walker Evans, on the one hand, and Christopher Williams, on the other. A close look at Evans’s “Tin Relic” photographs in American Photographs makes it easy to see that genealogical connection.

I owe the idea of drawing the two series together to Roger Willems, who sat with me and looked over them and suggested that they could and should be interwoven. I had treated them as two separate consecutive entities, which in many ways they still are, but they have deep filial ties to each other, and my hope is that they enrich each other on the walls and on the page in useful ways.

The earlier part of that question is much harder to answer, though. I think if I’m honest, the work flows from a mixture of rage, incomprehension, reverie, deep-seated fear and very, very fragile hope. I discuss some of the genesis of the series in my essay in the issue of Contact Sheet that accompanies the exhibition, but the impetus in the strict sense was most powerfully a feeling that our conventions are failing us and have been for some time, and a belief that, while some of the divisions that separate us from one another have gradually or rapidly been sundered, others are retrenching in fearsome ways, and a great deal is at stake in the mess of all that. Those instincts figured strongly, and then there were, of course, the gradual revelations of the photographs as they came in fits and starts and sent me back out into the world to try and look again.

But I think you’re also asking me what the work itself is about, and I would say that it’s an attempt to look at the ways in which we are separated from one another, an attempt to look at the various forms of violence and fear that that separateness produces, an attempt to think through the usefulness of violence and fear, the arbitrariness of it, the pitilessness of it, its history and its irreducible links to the complex agency of the photographic image, and to patriarchy in a broad sense.

Yes, we’re living through a tumultuous moment, in many respects. As an artist and teacher, I’m wondering if you can speak to your feelings about this, and your roles in creating and participating in important conversations.

Unquestionably, the place where these issues are most urgent for me is in the classroom, where I’m responsible for trying to figure out how to help a generation of students learn to question the legacy they’ve been presented with, as well as the ways they’ve been taught to see it, and to encourage them to stake a claim to finding their place in all this tumult. The most profound risk in that endeavour is that they become apathetic or begin to despair, but the odds are extraordinarily steep—especially for public school art students like those I teach at Purchase College, and, as we know all too well, particularly for students of colour.

The students in my classroom embrace circumstances in which whole tectonic plates that undergird their worldview are pulled apart, and they do so regularly. That takes a certain kind of courage sorely lacking in those who have the power to effect systemic change. I feel an obligation to try to meet that courage, not only in the classroom but in my work, whether written or photographic, and it’s an enormous privilege to get to do those things for a living.

I do sometimes worry that my mission statement for teaching hasn’t changed much since I applied to graduate school five years ago, but then I read that Mike Ditka had said…

My choice is that I like this country, I respect our flag, and I don’t see all the atrocities going on in this country that people say are going on. I see opportunities if people want to look for opportunity. Now if they don’t want to look for them, then you can find problems with anything, but this is the land of opportunity because you can be anything you want to be if you work.

…and I’m reminded that the question of seeing matters a very great deal, even—if not especially—in art school. I remember in a roundtable organised and published by Artforum at the height of the debacle at USC Roski, Frances Stark said that art “is a magical technology.” I believe that wholeheartedly. I believe it more, paradoxically enough, even as images act as a pretext for, and a retroactive justification of the murder of unarmed people of color at a pace and with an abandon that’s extraordinarily hard to fathom. Art can make us present to ourselves and to each other in tremendously complex and visceral and—perhaps most exciting of all—timely ways. That seems like a worthy task, and a goal worth fighting for to me.

I think if I’m honest, the work flows from a mixture of rage, incomprehension, reverie, deep-seated fear and very, very fragile hope

Most definitely. It’s not necessarily that there are more awful things happening around the globe today, but as we have become increasingly visual and increasingly instant, images and videos have become so present in our consumption of news. It’s powerful and amazing, and often difficult and distressing. We never want to find ourselves desensitized to these images and stories, and yet it seems that daily we must find a way to process them.

I think in relation to the proliferating videos and images of forms of state and non-state violence, the struggle is to meet the kind of model of spectatorship that Ariella Azoulay outlines in The Civil Contract of Photography. In it, she argues that photography makes possible a set of social relations that demonstrate the implicit existence of a civil contract between people that is not mediated by the state or any other institutional force. Her book identifies in this “civil contract”—and thus in the sociality of photography—a “civic duty toward the photographed persons who haven’t stopped being ‘there,’ toward dispossessed citizens who, in turn, enable the rethinking of the concept and practice of citizenship.”

That might sound a little abstract—at least as I’ve poorly paraphrased her work—but if you think about the radical reversal in the kind of looking we can bring to JT Zealy & Louis Agassiz’s slave daguerreotypes as against the mode of looking they were intended to produce, it quickly becomes clear that we can address ourselves to those people depicted in—and subjected in—those images in a way that Agassiz and Zealy would have rejected. We can do so precisely because we can respond to a humanity in them that the photograph reflects, even if it was disavowed in the political orthodoxy of Columbia, South Carolina in 1851.

That’s an instance of us responding to a “duty toward the photographed persons” which in turn enables us to “rethink the concept and practice of citizenship.” It’s especially relevant in contemporary terms in relation to the systemic inequities that separate those who enjoy the rights and protections of full citizenship from those who do not, whether we think in terms of race, class, gender or religion. The inequities of American citizenship are being revealed in this relatively recent and unceasing stream of videos, and they present a tremendously important challenge to us in terms of the responsibilities and pressures that go along with citizenship and looking.

Azoulay’s is a high bar to meet, particularly because the frequency and the pitilessness involved in these murders—as I would often describe them—is so devastating and impossible to absorb. In that sense, one might argue that her idea is too utopian, but I’d argue that we live in country—the United States—that is reflecting back to us in increasingly lurid and distressing detail the limitations of a set of conventions that have been failing for some time, and that have been killing people by the hundreds and thousands in the process. What good is conventional imagination in those circumstances, and how is its adoption not an implicit endorsement of the status quo? On the one hand, it’s easier not to be utopian if your identity doesn’t constantly leave you exposed to the imminent risk of death. On the other hand, as David Graeber has argued, the neoliberal project was never economic but socio-political, and one of its principal victories has been the radical dismantling of political imagination. Pictures can help here, I think.

You studied Philosophy and French at Oxford University in the UK, before completing your MFA in Photography from Virginia Commonwealth University here in the US. America is very much your home now, yet you straddle the ocean. How did being a “foreigner” to the US inform your perspective, and your photographic process?

Not to be funny, but I obviously realised before even moving here that I could very easily be shot dead for doing nothing illegal or inappropriate whatsoever, and that I particularly ran that risk in interactions with the police, and that I could hope for little to no institutional support in such circumstances were I to fall victim to them. That thought—and the attendant terrors and risks and accommodations it requires to live with it daily—is never all that far from my mind in this country.

But I remember this very questionable line from Edward Zwick’s 1998 film, The Siege, where Annette Benning’s character, who has worked in the Middle East as a CIA operative for many years, says that Palestinians “seduce you with their suffering.” Leaving aside the troubling reversal of power dynamics implicit in that description of Palestinians’ power over the American government, I think it would be fair to say that I fell in love with the art that suffering has produced or inspired in this country long before I had ever visited it. I’m thinking of the wound in Billie Holiday’s voice, for instance, or the fire in Nina Simone’s, or the “incipient delirium” Tod Papageorge identifies in Robert Frank’s The Americans, or the zealotry of De Niro in Taxi Driver.

It seems to me that where other European nations might understand themselves as brute historical facts, America conceives of itself as a project, which makes history and the future significant in a distinctive and remarkable way. It’s a place permanently in process, not as an incidental feature of how time works, but as an explicit and integral feature of this country’s DNA.

In Fred Moten’s 2003 essay, “Black Mo’nin’,” he quotes extensively from a book by Nathaniel Mackey called Bedouin Hornbook, in which Mackey writes the following about the use of falsetto in Al Green’s music:

[T]he uncanny coincidence is that the draft of your essay arrived just as I’d put on a record by Al Green. I’ve long marveled at how all this going on about love succeeds in alchemizing a legacy of lynchings—as though singing were a rope he comes eternally close to being strangled by. … [T]he deliberately forced, deliberately “false” voice we get from someone like Al Green creatively hallucinates a “new world,” indicts the more insidious falseness of the world as we know it. (Listen, for example, to “Love and Happiness.”) What is it in the falsetto that thins and threatens to abolish the voice but the wear of so much reaching for heaven? … [T]he falsetto explores a redemptive, unworded realm—a meta-word, if you will—where the implied critique of the momentary eclipse of the word curiously rescues, restores and renews it: new word, new world.

I think these are the sorts of experiences—incubated in periods of extraordinary distress and injustice—that have been “alchemised” into much of the American art that I love, and they first drew me to the United States. Then there’s the vastness of the country, the compendious nature of it, and the impetus that that vastness provides for constant curiosity, which is essential for a life in the arts. The word “possibility” is certainly fraught in our times, but it seems more sayable in a country obligated—in however limited a fashion—to be positively disposed toward transformation and the future if it is to be itself at all.

As to how being a foreigner here has affected my process, it certainly makes certain interactions much easier because people in many parts of the country are unused to meeting black men with posh British accents. That certainly buys me a little time, and it often mitigates people’s scepticism to some extent, or transforms it into curiosity, which is so much easier to work with when you’re out trying to make pictures of the world. I am free to claim ignorance in many situations where one might reasonably expect an American to know better, and I do so quite often if it gets me closer to what I want or need. Though it’s utterly ridiculous to do so, many Americans take me more seriously because of my accent, which is especially hilarious because British culture falsely prides itself on not taking oneself seriously, which means we are experts at talking shit, and I do this as often as I can.

But at the same time I have a certain freedom that I treasure in making work here that comes from my ignorance, and the license it gives me not to accept a particular order of facts or a particular history as the thing against which to measure whatever hypothesis I’m attempting as I work. My friend Bryan Schutmaat introduced me to Richard Hugo’s essay, “The Triggering Town,” five or so years back, and Hugo’s argument about the small town a poet needs to write from has stayed with me ever since:

The poem is always in your hometown, but you have a better chance of finding it in another. The reason for that, I believe, is that the stable set of knowns that the poem needs to anchor on is less stable at home than in the town you’ve just seen for the first time. At home, not only do you know that the movie house wasn’t always there, or that the grocer is a newcomer who took over after the former grocer committed suicide, you have complicated emotional responses that defy sorting out. With the strange town you can assume all knowns are stable, and you owe the details nothing emotionally.

What that means for me as a photographer and a foreigner is that I need not be hidebound by biography, or by some instinct to conform to objective fact in attempting to get at something true and significant. I think Philip-Lorca diCorcia said in The Genius of Photography that “a photograph can tell you something true, just not about that particular person or place,” and I tend to believe that that freedom is essential, and that that complexity has everything to do with where and how we encounter one another as strangers in this world. So I’m intent on working in that gap, or attempting to embrace the inevitable contradictions that come along with that sort of ambiguity, and I find I can do that quite instinctively here, because America is a town I’ve “just seen for the first time.”

I’m curious to hear more about your process, both of image-making and the collecting of found 4×5 negatives. Are you exploring antique stores or watching online auctions all of the time? And now that you’ve woven these projects together, are there moments where a found negative has sparked your interest in going out to find a photographic subject, or vice versa, where a photograph you’ve made has sparked a profound connection with one of the found negatives?

I actually acquired all the archival negatives online without leaving the comfort of my own home, so I’ve not had to step foot into a thrift store or go to a flea market to obtain any of the appropriated photographs in All My Gone Life. In that sense this work emerged from a diametrically opposing methodology to Tacita Dean’s FLOH, for instance, where she collected vintage photographs from flea markets over a number of years and then culled them into an elliptically sequenced run of images in a beautiful book.

But All My Gone Life also includes a series of my own 4×5” photographs alongside these appropriated negatives, and eBay made it possible to search for and acquire negatives specifically, rather than prints. That distinction was important to me. It meant embracing an equivalence according to which my photographs are of no greater significance than those I’ve appropriated, and it meant reckoning with the photographic rhetorics I have inherited from the past. As I make this work, I understand myself to be participating in a history in which I’m implicated and imbricated in a variety of ways, and that history shapes my sense of the choices available to me. That’s one of the fundamental issues that the work across both series attempts to address: the extent to which the environment in which we live acts on us, and the extent to which we act on it, the extent to which our choices are shaped by disavowed but fundamental forces, whether historical or contemporary… So there was a resonance there that seemed meaningful, and working with archival negatives also offered me the opportunity to think about voices and authorship as they’re invoked by my subject matter in a polyphonic way.

As to your question about influence, it’s tricky to be certain about how the archival negatives affected the production of my own photographs as those two strands developed in parallel. I’m not denying for a moment that they had a reciprocal impact on each other, but it’s difficult to be sure about how to disentangle those things…

The most clear recollection I have of the differing emphasis that the archival negatives produced in my sense of the work was in the way they made me think and feel much more acutely and consistently about the body. Rukeyser’s Despisals poem draws an equation between one’s body and the city, and argues against the dereliction of either one. I think I hadn’t really delved into the complex forces that cut into and through the body, and their relation to our sense of self and of place quite as much as I could have by the time I finished the first series, and the archival negatives impelled me to redouble that effort in the second.

As I made my own photographs and acquired the negatives of other photographers, I started to notice certain resonances or productive tensions between the pictures, but I didn’t read the appropriated negatives as roadmaps for new photographs to make or, conversely, my own photographs as an inventory for new negatives I might acquire. I’m most interested in, and excited by, the unexpected ways in which the pictures resonate visually, and I’m intent on trusting my faith in the notion that visual meaning is an expression of other equally significant meanings, and therefore I trust that the pictures can lead the way. It might seem an odd thing to say, but I find I’m most thrilled by the interconnections between the archival negatives and my own photographs when they strike complementary “notes,” and begin to sound like they’re meant to be phrased in relationship to one another, so I try to hold onto that instinct as I move between the two.

These projects and the exhibition itself draw their titles from the writing of poet and political activist Muriel Rukeyser, in particular her poems Waterlily Fire and Despisals, which you have quoted. What powerful texts. How did you first encounter her writing, and in what ways do you see it in conversation with your images?

I have to admit that I discovered Rukeyser’s poetry in the most anodyne way. I have had the Poetry Foundation app on my phone for a number of years, and on occasion when I’m waiting for something or someone, I use its “random” feature to discover a new poet and start reading their work. I did that in 2011, and I stumbled across Murmurs from the earth of this land, and was dumbstruck. I couldn’t recall the last time I had experienced that sort of force of recognition and estrangement. She seems able to collapse space in on itself, and draw astonishingly eloquent, utterly illogical links between those everyday concepts that mould the limits of our everyday reality.

It was a while before I read Despisals, which is the poem that gave me some amorphous but powerful sense of direction as I made the first series, Our Present Invention, whose title comes from a stanza in the poem where she writes:

Among our secrecies, not to despise our Jews

(that is, ourselves) or our darkness, our blacks,

or in our sexuality wherever it takes us,

and we now know we are productive

too productive, too reproductive

for our present invention —

Rukeyser crafted something that struck me as both beautiful and forceful, most especially in her insistence on the interdependence of opposites—on their dialectical relationship—and on the porosity of the physical and the retinal. It seemed to offer me a way in at a point when I was fumbling around at the edge of nothing much.

I love that, when the world just quietly presents something at the right moment.

I’ve been fortunate to go out photographing with Irina Rozovsky on a couple of occasions over the past few years, and it’s incredible to observe how unerringly unusual things happen when she’s out working. I’ve only ever seen a squirrel tamer when wandering around in her company while she’s making pictures…

I think there’s something to the notion that you can lock in to some numinous frequency at which the world offers you up gifts utterly germane to what your work is about. I think that it happens if you keep going out, and keep attending to what your photographs seem to say and need. I think photographers are always in a dance with luck, and while for some people, the extent to which fortune plays into photography undermines the creative act itself—or our claims to it—I’d argue that it’s creative to set about being in the world looking in the way that we do, and that chance is something to be embraced wherever possible.

Manuel De Landa introduced his book, A Thousand Years of Nonlinear History, with this Lucretius quotation that really gets at the virtues of steering off the beaten path and welcoming chance and deviation as constitutive parts of life:

When atoms are travelling straight down through empty space by their own weight, at quite indeterminate times and places, they swerve ever so little from their course, just so much that you would call it a change of direction. If it were not for this swerve, everything would fall downwards through the abyss of space. No collision would take place and no impact of atom on atom would be created. Thus nature would ever have created anything.

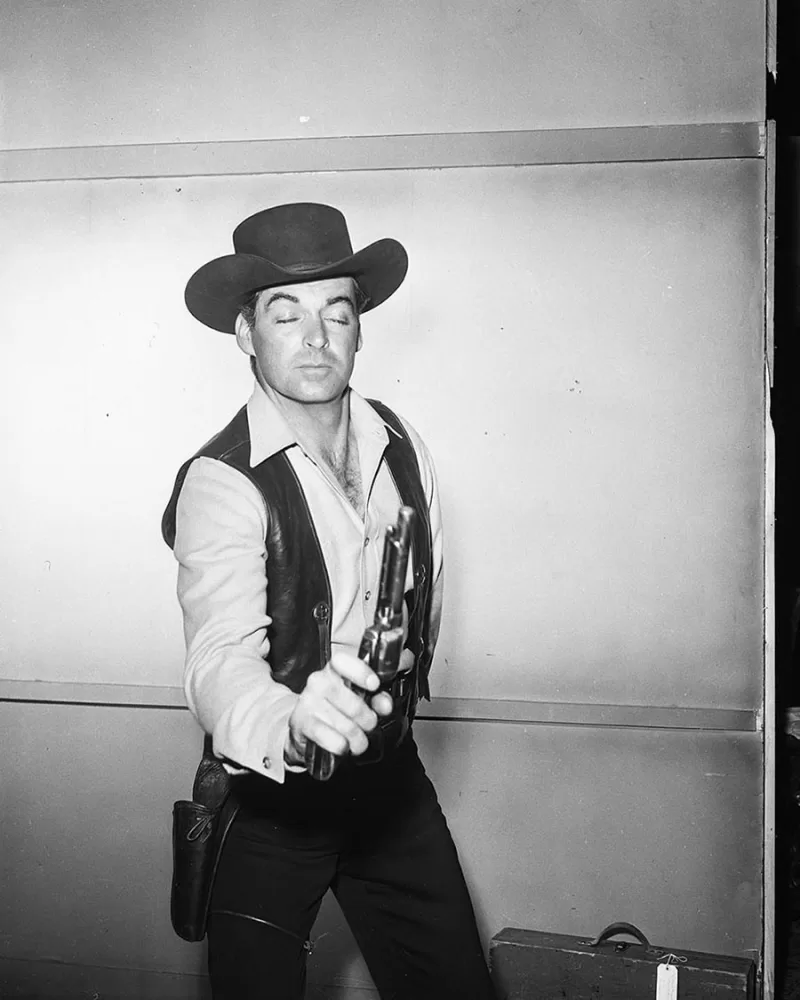

There’s an unsettling humour about One Wall a Web, especially in the way you’ve sequenced and paired photographs. While flipping through the image selections the other day, you really couldn’t help but laugh out loud at a few of them. It seems that sometimes the humor found in certain images is brought on as a way of dealing with the absurdity and juxtapositions. Recognizable characters like Shirley Temple and John Wayne are interspersed with portraits of everyday people, still lifes, and landscapes that are—though sometimes subtly—politically and socially charged. Can you talk about the humor in your work, as well as the gravity of it as a whole?

I remember reading Fredric Jameson’s essay on Hans Haacke in the Unfinished Business catalogue five or six years ago, in which he discusses Haacke’s approach to making political art in the era of simulacra, and he argues that “it is no longer possible to oppose or contest the logic of the image-world of late capitalism by reinventing an older logic of the referent (or realism). Instead, at least for the moment, the strategy which imposes itself can best be characterised as homeopathic: ever greater doses of the poison—to choose and affirm the logic of the simulacrum to the point at which the very nature of that logic is itself dialectically transformed.”

That essay is thirty years old at this point, but if you think of the political satire in Haacke’s Taking Stock, for instance, and consider Donald Trump’s candidacy for President—and the very, very real possibility that he might win*—it’s apparent that we have not transcended the challenges of a neoliberal political and cultural order driven by spectacle. Or, to put it another way, I’m opting for “first as tragedy, then as farce.”

The fissures that my work points toward, or tries to unpack are visceral, often deadly, and of deep and urgent significance. I don’t take them lightly. But I think any number of the profoundly entrenched conventions that undergird patriarchy are both arbitrary on their face, and utterly ridiculous upon close examination: Cliven Bundy and his posse can confront federal law enforcement officers with automatic weapons in a standoff after refusing to pay grazing fees and emerge unscathed, while unarmed black men obeying police instruction are fatally shot in the back at traffic stops or while climbing the steps to their homes. While three drug offenses can get you life in prison, evidently Bernie Madoff masterminded a $65 billion fraud that bamboozled the regulatory infrastructure of the US government entirely on his own…

The game is patently rigged, and that fact is both tragic—in the devastation that it causes daily—and farcical—in its patent inconsistencies—at the same time. I remember listening to Slavoj Žižek a year or two ago arguing in a lecture or an interview that the best strategy of resistance against neoliberal capitalist conventions was to find points of weakness where its hypocrisies could be clearly seen, and to exacerbate that weakness until the logic is robbed of its powers of normalcy or self-evidence. I’m after something similar in the work’s use of humour, albeit I don’t mistake picture-making for collective political action of the sort that is clearly and urgently required in great measure.

My hope is that the groupings and sequences of my photographs can exacerbate the intrinsic hypocrisies of the cultural conventions that they address—perhaps in comical or at times dyspeptic ways—and that certain things which are typically understood to be diametrically opposed can be shown to exist in proximity—or better yet interdependence—with one another: terror with desire, visibility with erasure, civility with subjection, fantasy with reality and so on…

I’m most interested in, and excited by, the unexpected ways in which the pictures resonate visually, and I’m intent on trusting my faith in the notion that visual meaning is an expression of other equally significant meanings, and therefore I trust that the pictures can lead the way.

The issue of Contact Sheet that accompanies your Light Work exhibition has been an opportunity for you to experiment with your work in book form. Is this something you plan to elaborate on at some point, maybe as a monograph or artist’s book, when you feel the projects have reached a close? Where are you going next with this work?

I’m basically finished as regards making the work. There are less than a handful of straggler images that I feel driven to make so I can sleep easy with leaving the second series behind, but I’m already itching to photograph other things, which feels like as good an indication as any that it’s time to move on. I hope to have a chance in the coming couple of months to tie off those loose ends, and I also hope to publish the two series in a single book at some stage in the near future. The generous invitation from you and the team at Light Work to show the work feels like the beginning of a process of putting it out into the world, and I’d very much like for a book to be a central part of the work’s entry into the lives of other people.

I’m also certainly very eager to put the work up on the wall, and the show will be a wonderful chance to see how those who are utterly unfamiliar with me, or with the series, might encounter and make sense of these images and read them in the context of their own daily lives. I relish the distinctions between the discursive context of the photographic book and the exhibition space, and after four years I have a fairly large number of images from both series which can be put to work in different ways, depending on whether they’re destined for the wall or the page, so that’s something I’m really excited to try out. But it does feel like where I want to go next with the camera is someplace quite distinct, and I hope that I can grapple with new and better problems as I do so. That’s something I’m only in a position to hope for because of the platform this work has given me as a point from which to look out toward something new.

One Wall a Web is on show at the Kathleen O. Ellis Gallery, 1 November – 16 December.