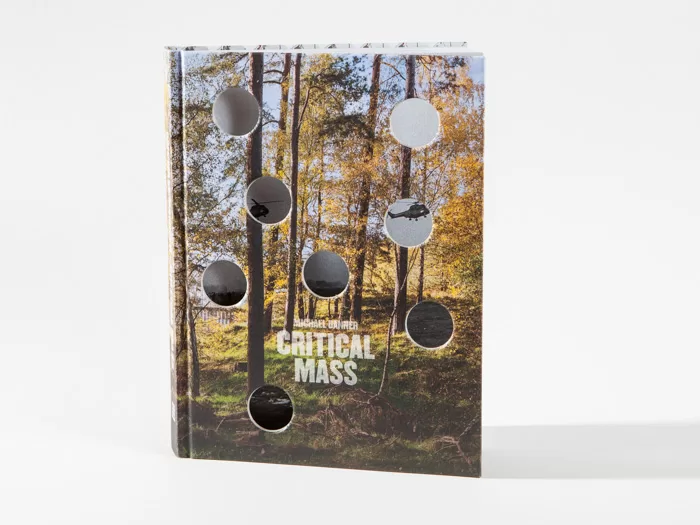

Michael Danner – Critical Mass

Artist: Michael Danner

Title: Critical Mass

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag

Year: 2013

BUY

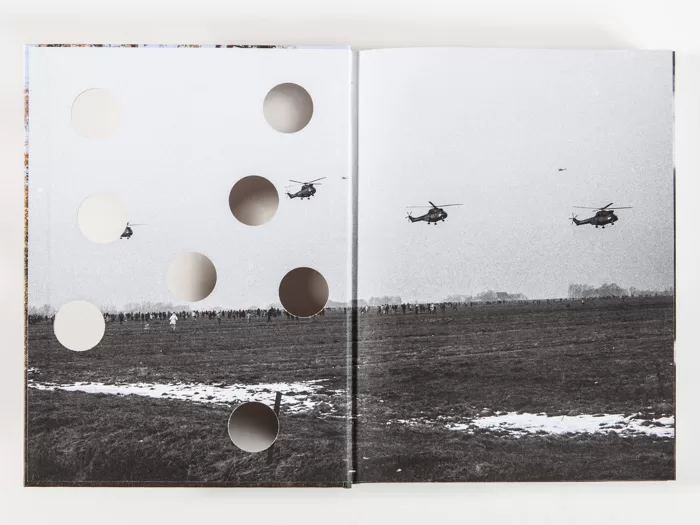

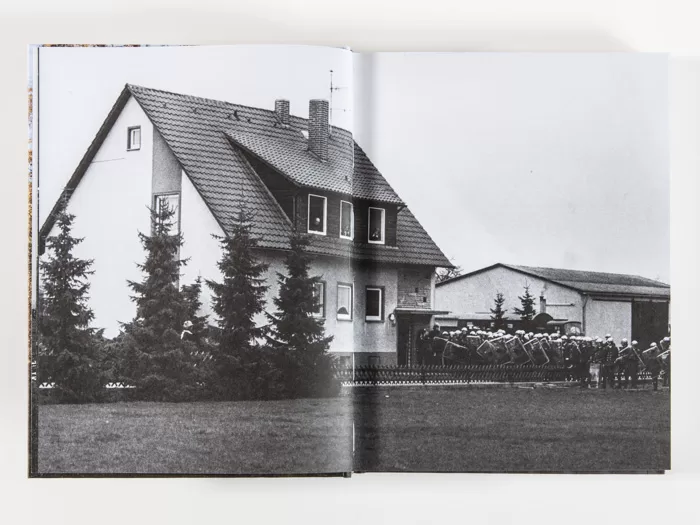

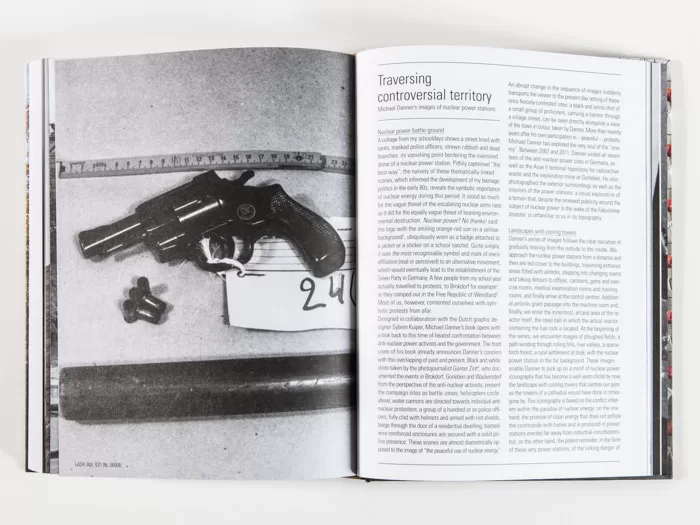

In Critical Mass, Michael Danner diligently documents German nuclear power plants, as well as the radioactive waste repository Asse II and the exploratory mine Gorleben. The book opens with a set of archival images taken by photojournalist Günter Zint during the clash between anti-nuclear power activists and the government during the escalating nuclear arms race of the 1980s. What is immediately captivating is the human conflict – in these noisy, grainy black and white photographs we bear witness to a cacophony of riot police storming residences and authority helicopters circling overhead, while road barricades and brave acts of individual protest driven by passionate convictions rage on – bodies laying themselves on the line in a conflict between two opposing ideologies and the attempted suppression of these individuals by state oppressors standing for ‘progress’.

Critical Mass can be defined as the amount of fissile material needed to sustain nuclear fission and, more generally, comparable to the tipping point concept. The book becomes particularly fascinating once you realise it is sequenced to evoke this very idea itself. At a certain point early in the book, these images give way to contemporary colour photographs taken of the plants. The clash between government and protester continued, hanging in a precarious balance until the movement reached a certain inertia – its tipping point, its critical mass – and fell in favour of the government. There are now seventeen nuclear power plants across Germany alone.

As the split in time happens, we are immediately greeted with an image of mundanity; of careful, clean consistency. This first image gives context for those that follow. Tracing a journey from afar to the innards, inside the plants, a distinct feeling of something calm but with a sinister underbelly emerges – the ever-present threat of nuclear catastrophe. As smoke plumes creep slowly, silently across the sky, houses switch on their lights as dusk draws in, and people holiday in caravans. (In an interesting parallel to this, we will see an ice cream van parked inside the grounds of a power plant later in the book.) ‘Business as usual’, they give out the message very clearly, and the protesters have retreated, long since left the scene.

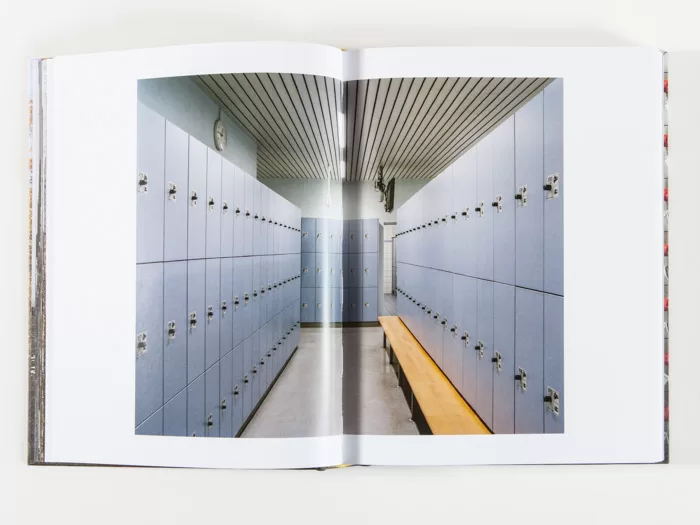

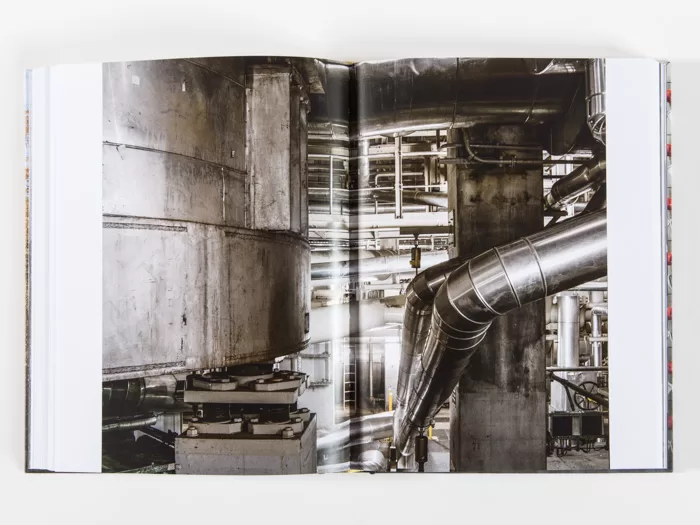

Inside the plants? Operational. Everything has a function, though none of that is explained or shown. The quiet, simple – and beautiful – repetition of shape and colour, motion, pipe, gate, and cog. The typological sequences of different plants; patterns emerge; the slow, consistent repetition of machinery – sterile. As Danner takes us closer and closer to the plants and crosses the borders into bright, futuristic and unfamiliar terrain we are greeted with a complete lack of human presence. Though people do inhabit these spaces, each turn of a page is pregnant with anticipation. A first aid dummy lies limbless on a medical examination room floor; a water bottle sits on the side in the control room; a backpack left by a chair; writing on a whiteboard in a board room. The images are perfect, too perfect, and reminiscent of the faultless sets that Thomas Demand would build from paper and card.

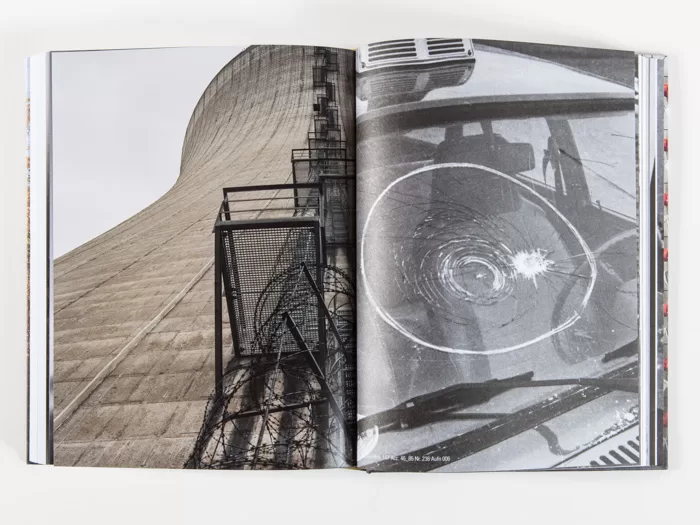

‘The peaceful use of nuclear energy’ is the term used, according to the essay that closes the book. Here there is quietness, but it is not peaceful – there is a distinct unease, an eeriness that lingers among the halls of the power plant. With each page-turn, we are granted further access into the crypt, past offices and gyms, board rooms and medical examination units, into the very core and further – through tunnels to the cooling towers, where condensed water vapour leaves us among thick fog, a long way from the spacious and bright engine rooms.

At the very end of the book, as the images taken by Danner cloud and fog nearer to abstraction and give way to the archival footage from the eighties once more, we observe final scenes – the damage, the aftermath of conflict – and, in a monumental pylon crashed sideways to the ground, we find a last apt metaphor for Critical Mass. Danner has allowed the camera to play the part of the silent, detached observer watching from behind a screen for us, perfectly – taking everything in but assuming no stance. The essay explains that ‘the images do not allow us to form definitive judgments on nuclear technology’ and this rings absolute. Though pressure seems to build throughout the book, Danner ultimately presents us with an objective view and passes it back to us, the viewer, to decide for ourselves.