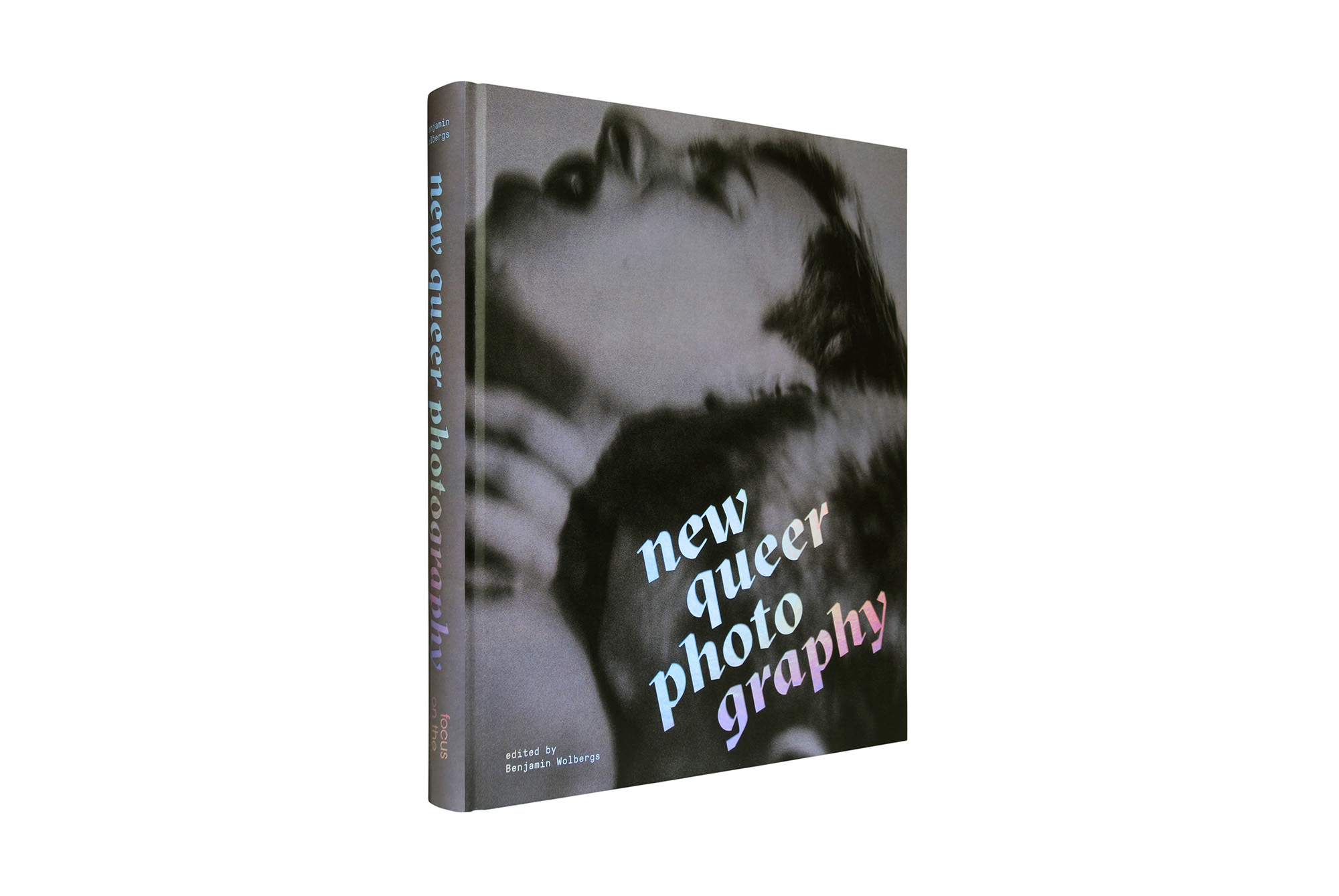

new queer photography – an interview with Benjamin Wolbergs

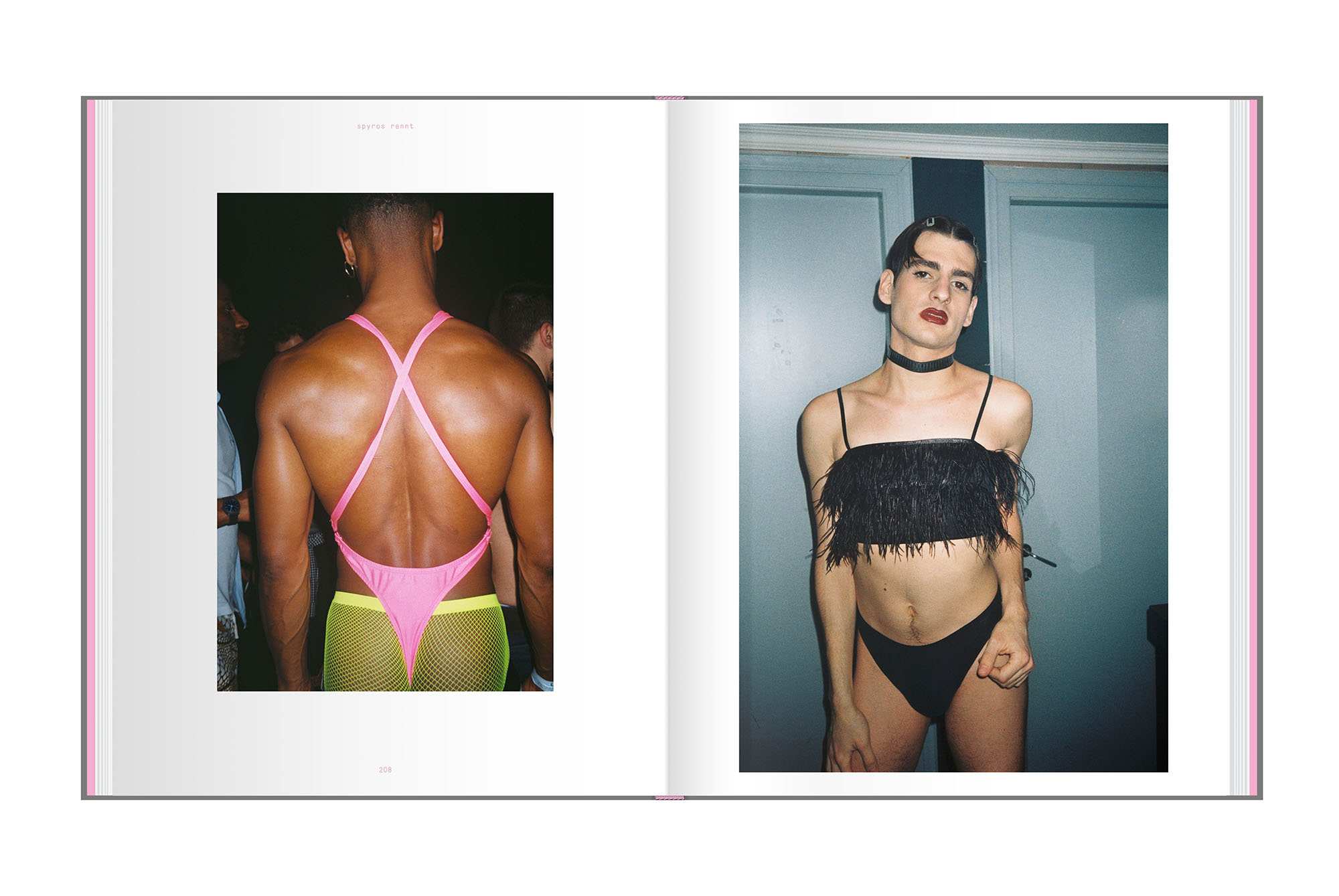

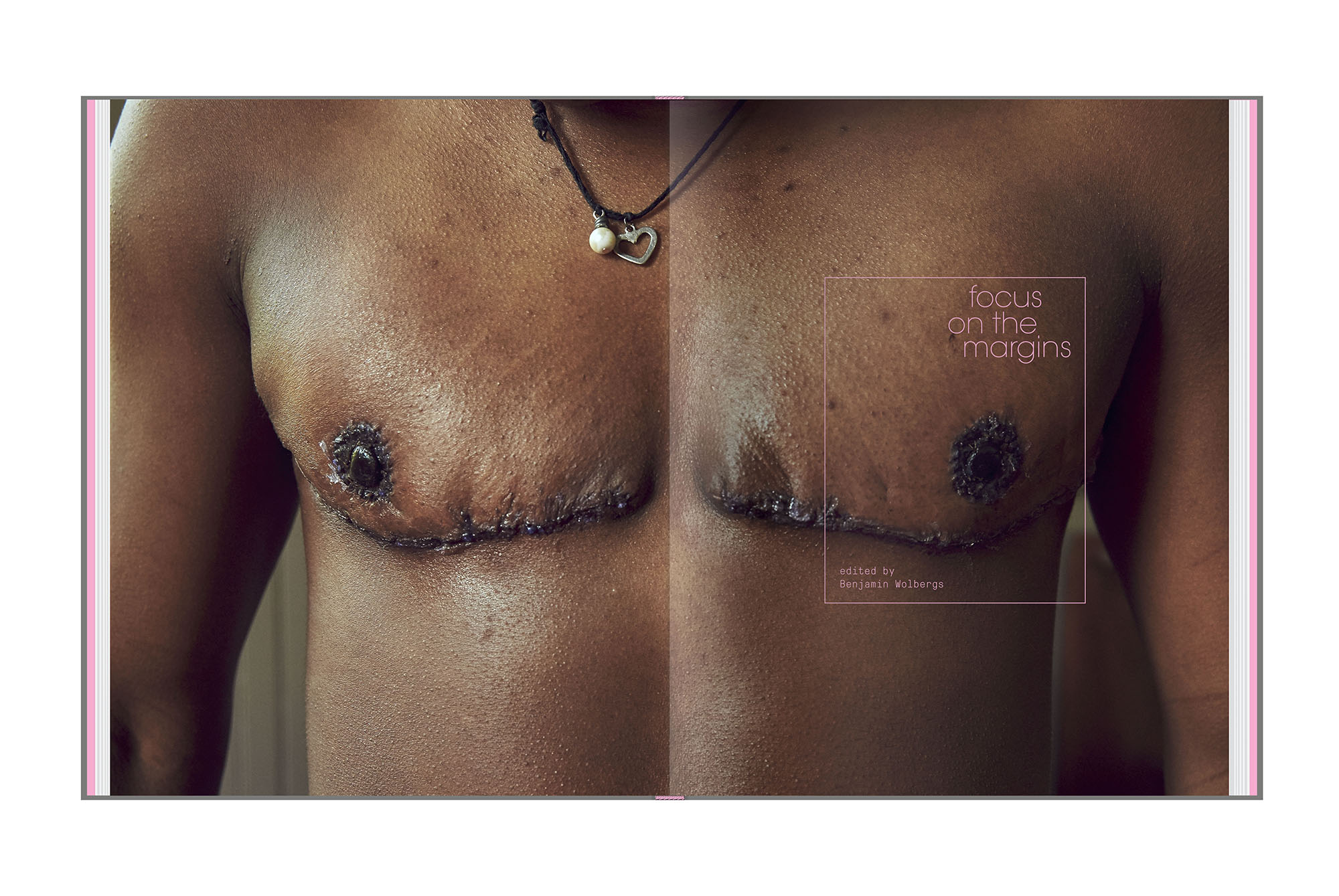

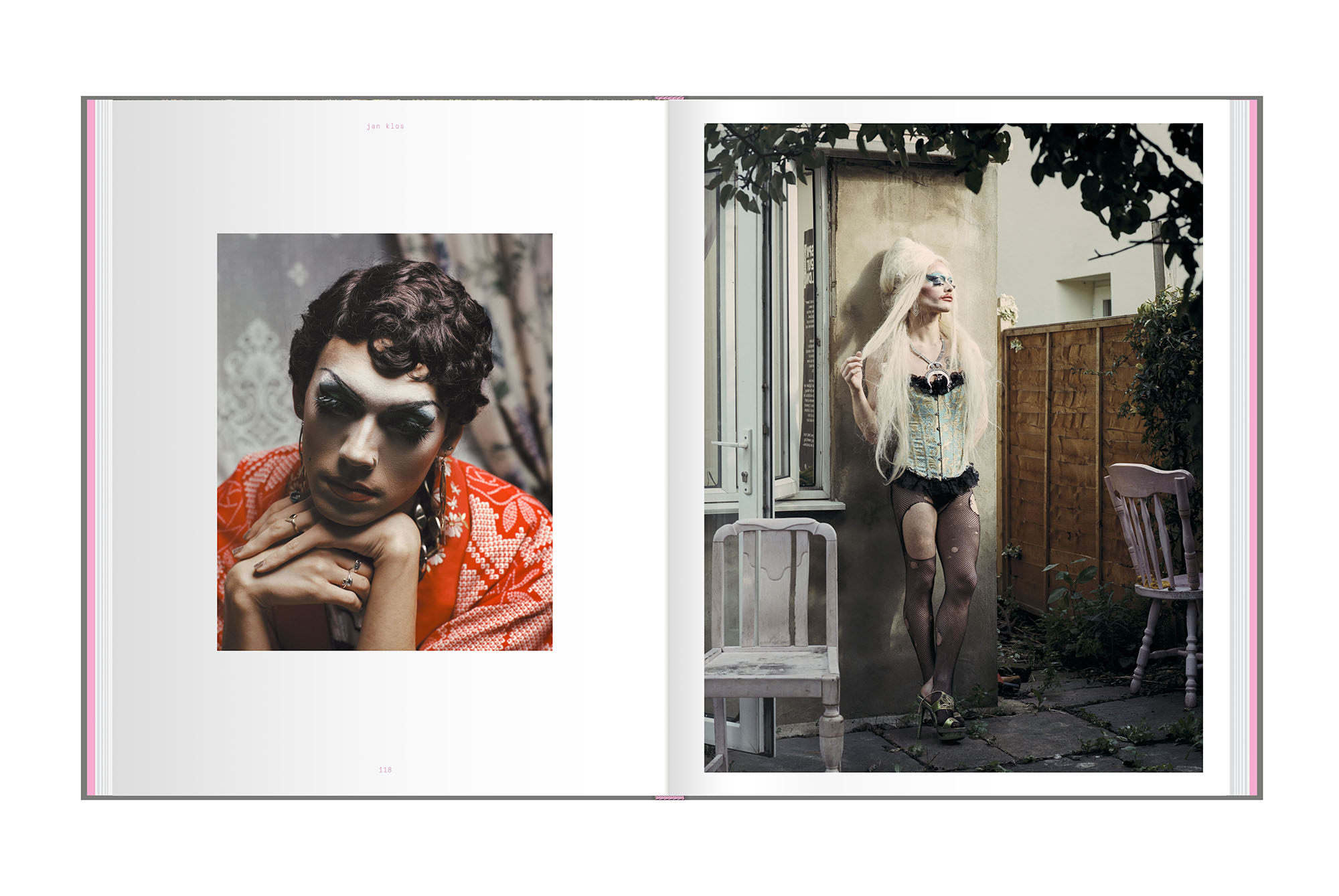

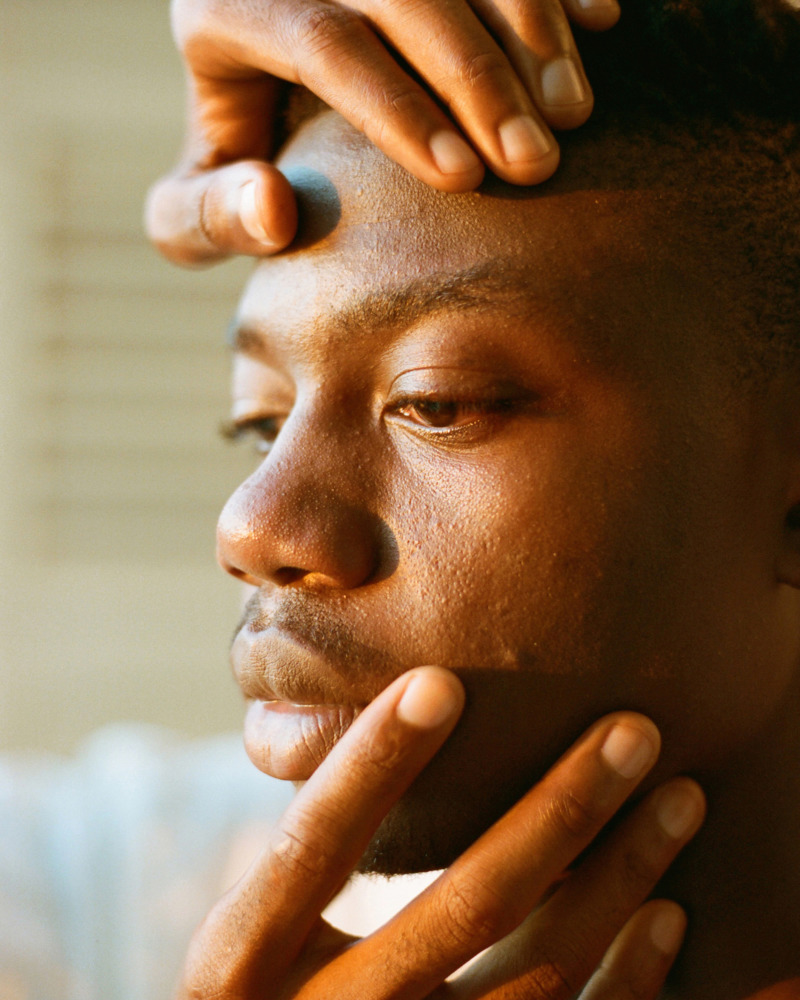

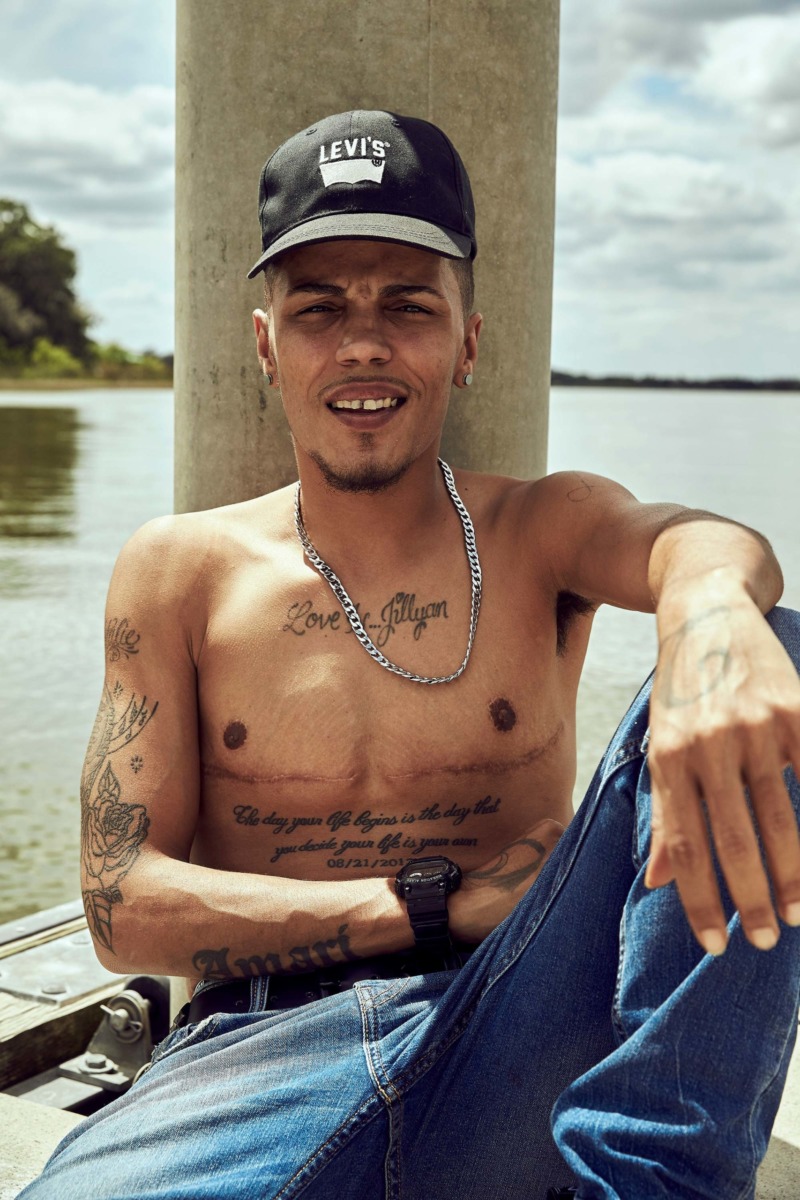

Benjamin Wolberg’s latest photobook, titled new queer photography (Verlag Kettler, 2020) is a visual exploration of queer culture and identity. Created as a reaction and response to outdated depictions of queerness, Wolberg’s project looks at the myriad understandings of the term ‘queer’ and, in doing so, establishes the idea that there is no universal way of defining it. As time has passed and society has progressed, so too has the queer community. It has grown and become more inclusive, encompassing new identities, aesthetics, shapes, sizes and colours.

In his search for contemporary depictions of queerness, Wolbergs pulled together forty modern photographic positions that represent different iterations on the subject. The images shown are from a selection of emerging and established photographers that form part of a burgeoning LGBTQI+ photography renaissance. Amongst them are Florian Hetz and Matt Lambert, who Wolbergs lists as particular influences during the early stages of the project. Prompted by these initial discoveries, he began to uncover a dynamic movement of people and ideas.

The resulting photobook is both a study of and a homage to this movement. It exists as a testament to the resilience of the queer community. It is a reminder that those who reside outside of a heteronormative society still face ostracisation, marginalisation, and even violence. But it is also a reminder of the strength and vision of these groups. The images in new queer photography are more than just beautiful artworks; they also serve to empower the photographic subject. They seek, in part, to answer, but also to pose questions; ‘How do we define queer?’ and ‘Who identifies with the term and what is their understanding of it?’

Can you tell us about your background?

I have been a Berlin-based freelance art director and editor for over 15 years. I work with a global selection of book publishers who hire me to create design concepts and layouts for their books, mainly in the fields of art, photography, design and architecture. Occasionally, I develop my own book projects, which I find to be the most satisfying part of my work. This was the case with my latest publication, new queer photography.

How did new queer photography come about and what was your inspiration for it?

It started about four years ago when I was working for TASCHEN on the layout of a book about physique photography that featured photos from the 1950s. The aesthetics and visual worlds of these photos were clearly intended to appeal to a gay audience. While doing this work, I asked myself: ‘What would a book with contemporary queer photography look like? What photographers, topics and styles would be included in such a book today?’

Around that time, I became aware of the work of Matt Lambert and Florian Hetz, and I started to look for other queer photographers. As my research intensified, a universe of incredibly talented LGBTQI+ photographers began to emerge with a wide variety of different styles that were beyond clichés and preconceptions. This is how the idea of new queer photography was born.

What did your selection process look like and what considerations did you make during the curation?

The selection process was very laborious and it took me over three years. I looked through a lot of books and magazines, but the most intensive research was carried out on the internet and social media channels. I scrolled through a tremendous amount of art, photography and LGBTQI+ related blogs and websites.

To decide which photographer and which image would make it into the book was a very time-consuming and difficult stage of the project. It was important for me to present as many different photographers, themes, and imaginary queer worlds as possible.

Which of the contributions to the book were personal highlights for you?

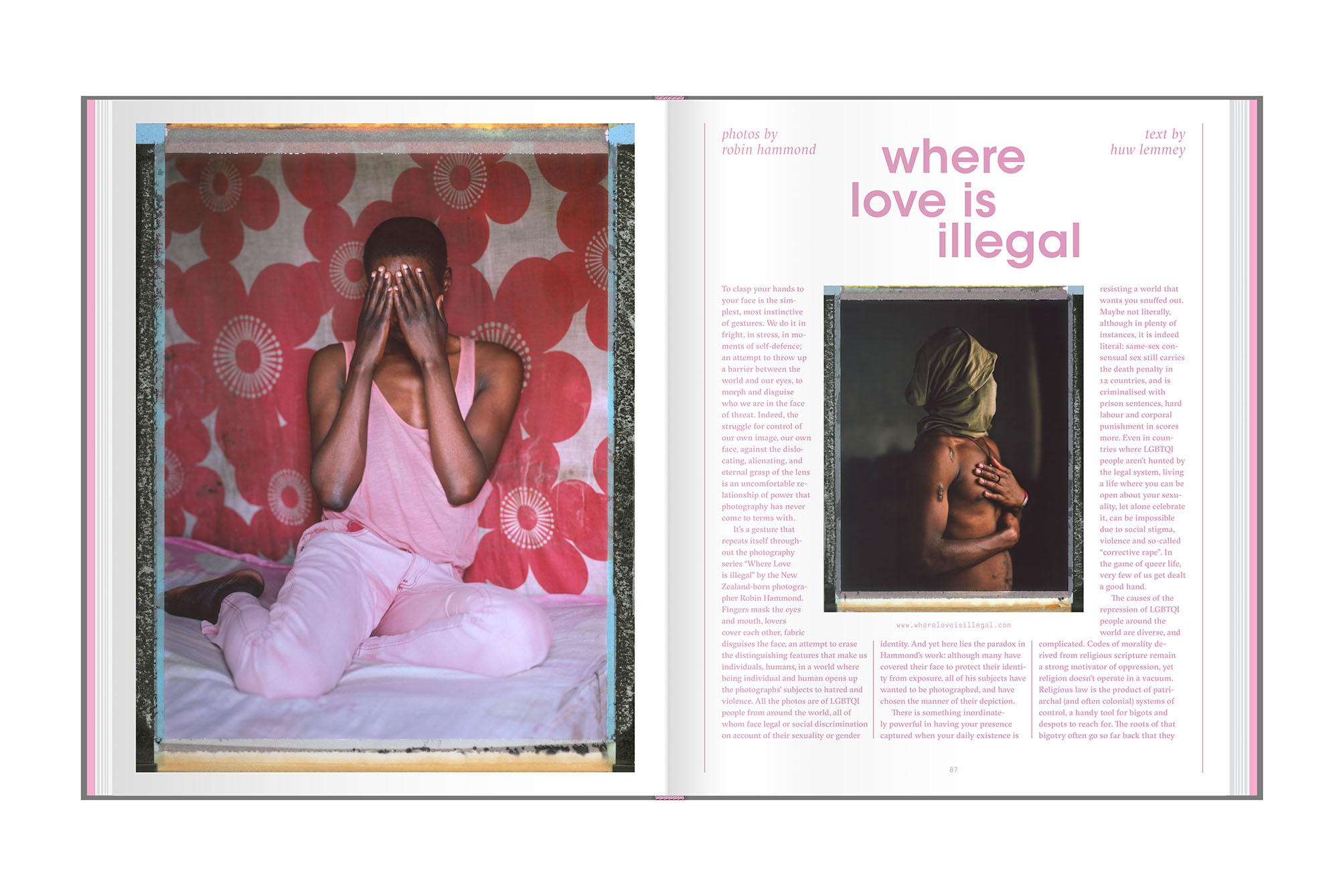

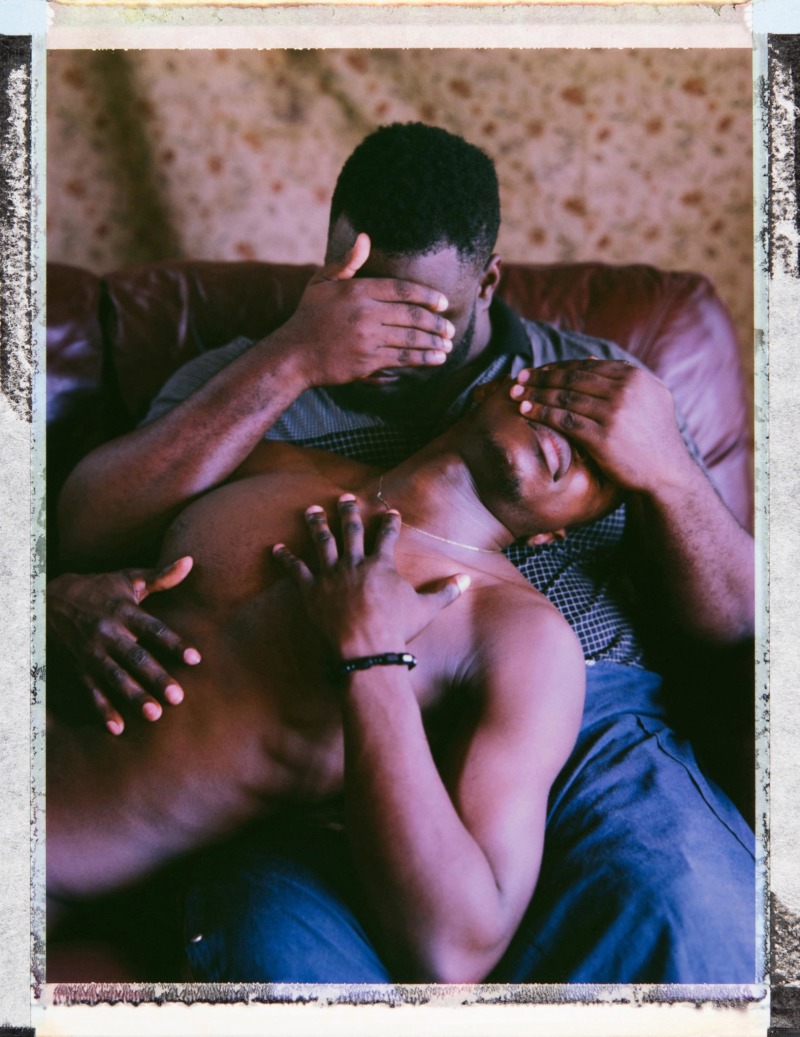

One of the series that touched me the most is Where Love is Illegal by Robin Hammond. This project features LGBTQI+ people from countries where same-sex love is criminalised and can lead to discrimination, physical and mental violence, imprisonment, torture, and even capital punishment. But a closer look reveals that there is a certain ambiguity at play here: the photographer’s remarkably sensitive approach allows the courage and strength of the portrayed subjects to triumph over their victimisation. Hammond’s images give them visibility and an opportunity to tell their own stories – despite the serious risks this entails.

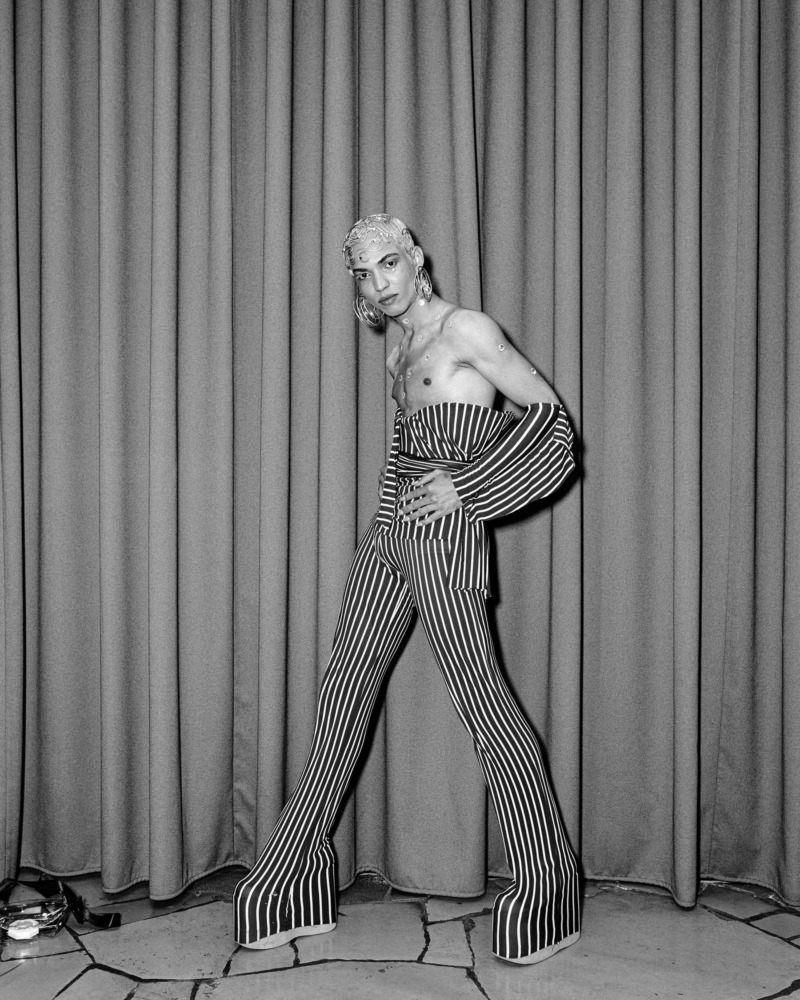

I also love the series Opulence by Dustin Thierry; in a lush black and white that recalls twentieth-century photographs of the underground scene, the photographer documents drag ball cultures in Amsterdam, Berlin, Milan, and Paris; scenes made up of racialised subjects who inhabit – even dominate – these portraits.

However, I was equally fascinated by and enthusiastic about all of the other images in the book. I am still not bored with them, even after working with them for the last four years; I think that says a lot.

With experience as both an editor and a designer, how did this duality in terms of your skillset affect the project?

I really enjoy working as both an editor and a designer on my own book projects. It means that I am in the rare and fortunate position of being responsible for and taking care of every single aspect involved in conceiving and making a book, from the theme and content to the layout and design, from the inside to the outside. I start with my initial ideas and begin to develop them, and then I move on to defining and curating the content and implementing the design concept.

With so many different definitions and understandings of the term ‘queer’, did you find it difficult to represent everyone’s perspectives within this book?

The book represents my own definition of queer, which I see as an inclusive umbrella term. With this publication, I have tried my best to present as many different photographers, themes, and perspectives as possible, trusting my intuition over more dogmatic approaches.

How did your own understanding of the term queer change during this process?

I would say that my personal understanding has only become fully formed during the course of this project. My interaction with the photographers, their ideas and their perspectives proved to be extremely valuable. What I’ve learned from this process and from speaking with the contributors is that there is no universal definition of queer.

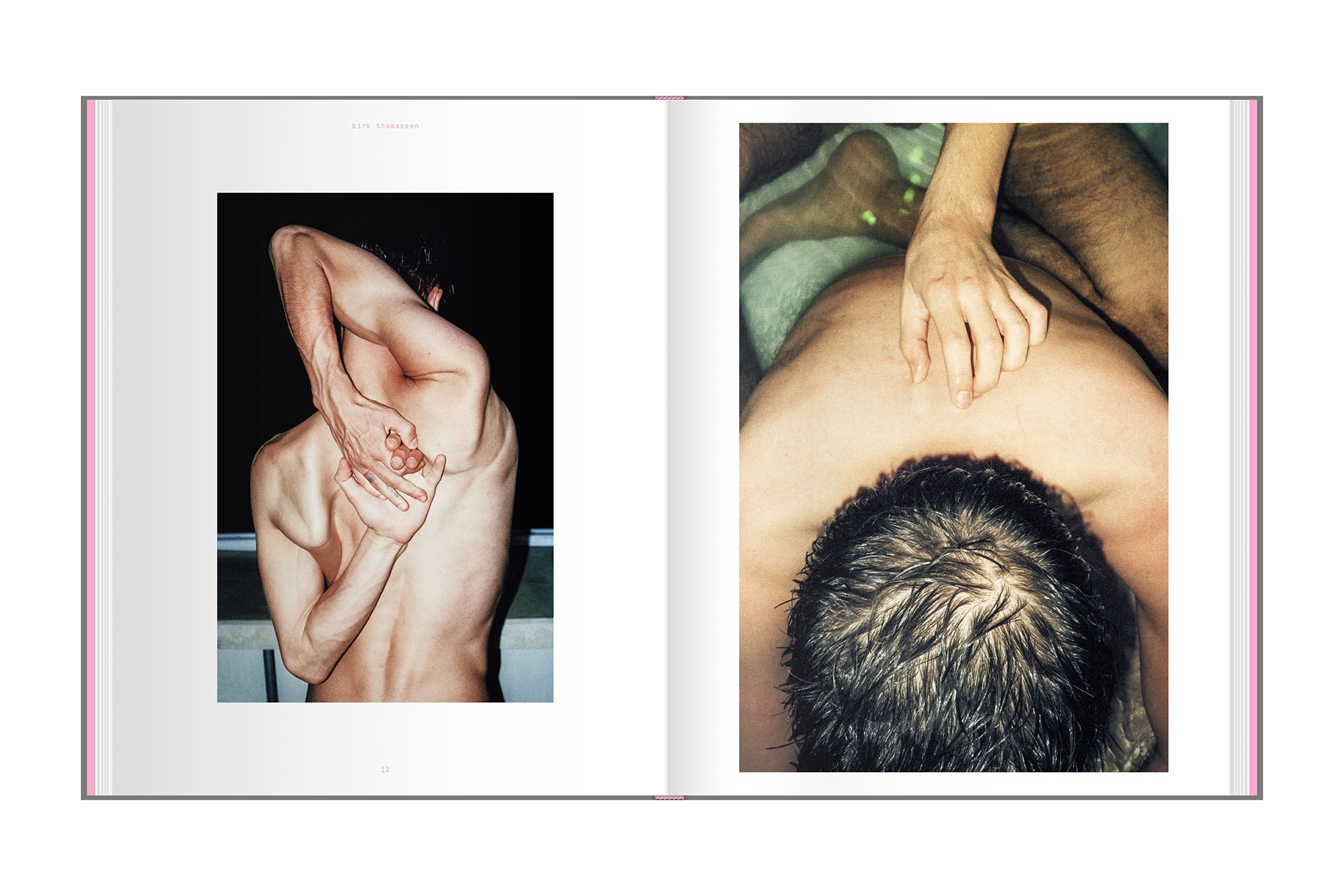

You’ve talked in the past of the “corrupting but affirmative power of pornography” within the queer community – can you expand on this?

Pornography has always been a part of queer culture; it’s a part of “normative” culture as well, but the queer community has always been more open to it. Think of Robert Mapplethorpe, who turned pornographic imagery into fabulous, aesthetic photographs. Of course, the situation today is very different; everybody can watch porn online. This has had an impact on society and has in turn changed the approach of queer photographers. This approach is just one way among many others of exploring queer imagery.

Do you think that photography as a medium is a particularly important outlet for queer culture?

I think every artistic medium is important and useful in communicating queer culture. But photography is perhaps one of the easiest to relate to, especially for people who are not familiar with the art world in general. It is a very valuable medium that can reach lots of people and new audiences.

Can you speak on the future of queer photography?

I think I can speak more about my own wishes and hopes for the future of queer photography: I hope that it will continue to gain recognition outside of the queer community, and I hope that it will never lose its fierce attitude.

new queer photography, Benjamin Wolbergs (Verlag Kettler, 2020) is available to purchase here.