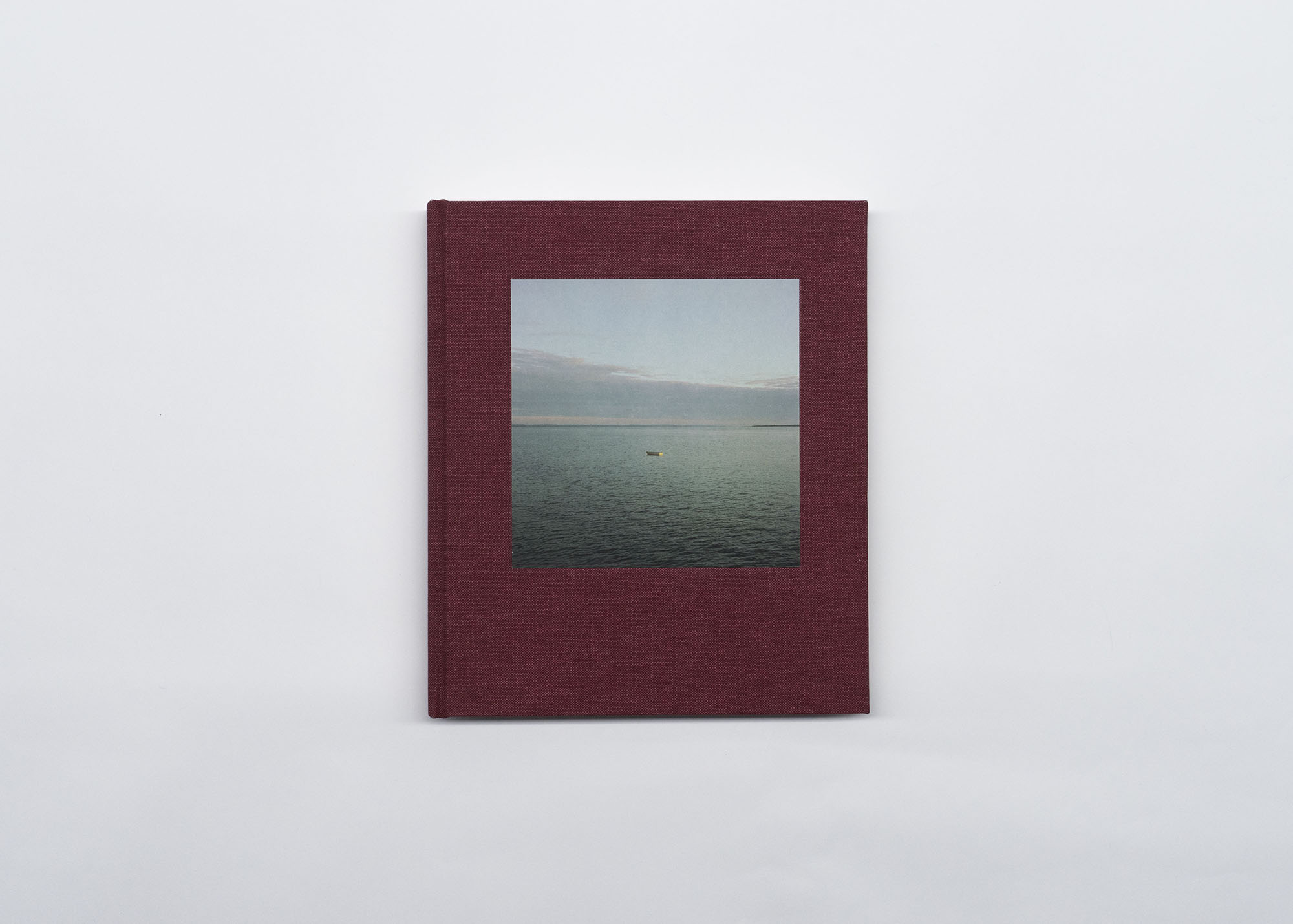

Ollie Hodgkins – The Moat

Situated 70km from Melbourne and accessible only by ferry is French Island, the largest coastal island off Western Port Bay in Victoria. With 70% being taken up by a national park, French Island is also home to a small population of 114 people; ‘drifters and dreamers’ who inhabit a place free of any local jurisdictions, and lacking in basic necessities such as roads, utility services or running water.

Ollie Hodgkins‘ The Moat (self-published) pays tribute to the island; one that is “a sort of microcosm for exploring the role of postcolonialism in shaping the cultures and attitudes of rural Australia.”

With being awarded a Commendation at this year’s Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award, we spoke to Oliver about his connection to the island, the importance of integrity in his portraits and the enigma of the vast, desolate and untamed place that is French Island.

What is your relationship to French Island? What was it that drew your interest to this place?

Before talking about my connections to French Island, I’d like to acknowledge a far deeper and more historic connection with the land which is that of its Traditional Custodians, the Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation, and pay my respects to their Elders past and present.

I first travelled to French Island as a child living in Melbourne’s suburbia. I had a pretty run-of-the-mill, privileged childhood. My playgrounds were city streets, parks and nature reserves hidden beneath roaring overpasses. I had this peculiar and adventurous friend, Ben, whose father owned an old guesthouse on French Island, perched atop a windswept hill not far from the island’s last remaining jetty. When I was ten years old, Ben invited me to spend a weekend there with his family, which led to my first experience of the island.

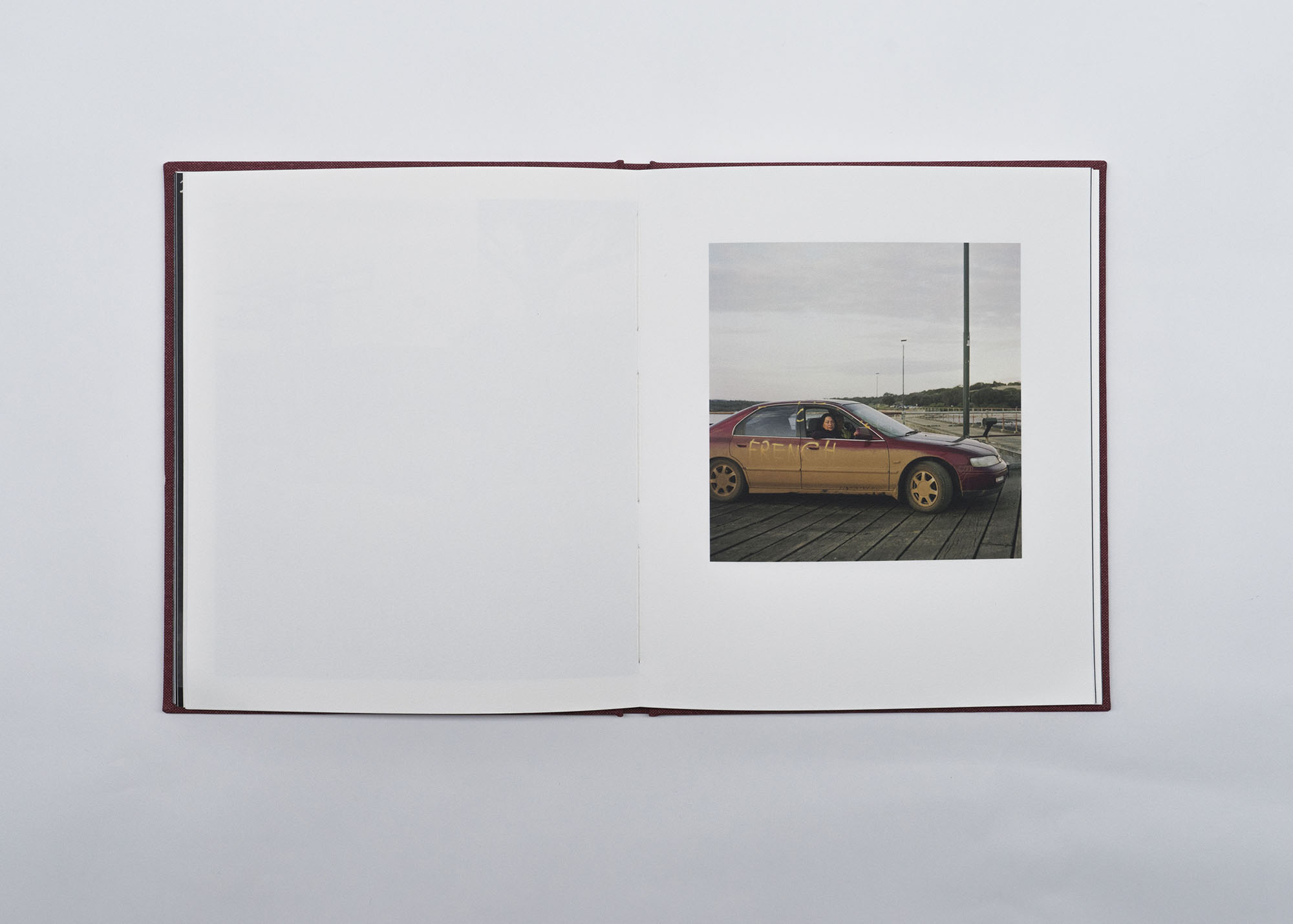

It completely captured my fascination. There was a sense of freedom and vastness that was so starkly different from anything I’d known. Seared into my memory are fleeting moments of my time there; of learning to drive cars down dusty pothole-laden roads, weaving through narrow tunnels of overgrown tea tree forest, and exploring vast coves with not a single person in sight. We would spend hours combing through derelict vehicles piled up in a huge car graveyard in the middle of the island, examining their contents and smashing windscreens for fun.

I returned several times after that, deepening my understanding and connection to how life was on the island. Then, in my early teenage years, my family moved away from the city to the Mornington Peninsula which lies across the water on the western side of French Island. Ben and I lost touch, and even though I was much closer to the island than him, I lost touch with it too.

It was only in my mid-twenties that I started taking photographs in the region, which prompted me to relive my childhood trips to the island. I began to realise how formative those experiences had been for me. On a whim, I called the guesthouse that Ben’s father had owned. The house had since changed owners, and the new owner invited me to check the place out. In a humorous twist of fate, he also happened to be the president of the community association, and the only on-site real estate agent. He introduced me to a group of residents, and before long I was transfixed by the island again.

French Island is a sort of microcosm for exploring the role of postcolonialism in shaping the cultures and attitudes of rural Australia

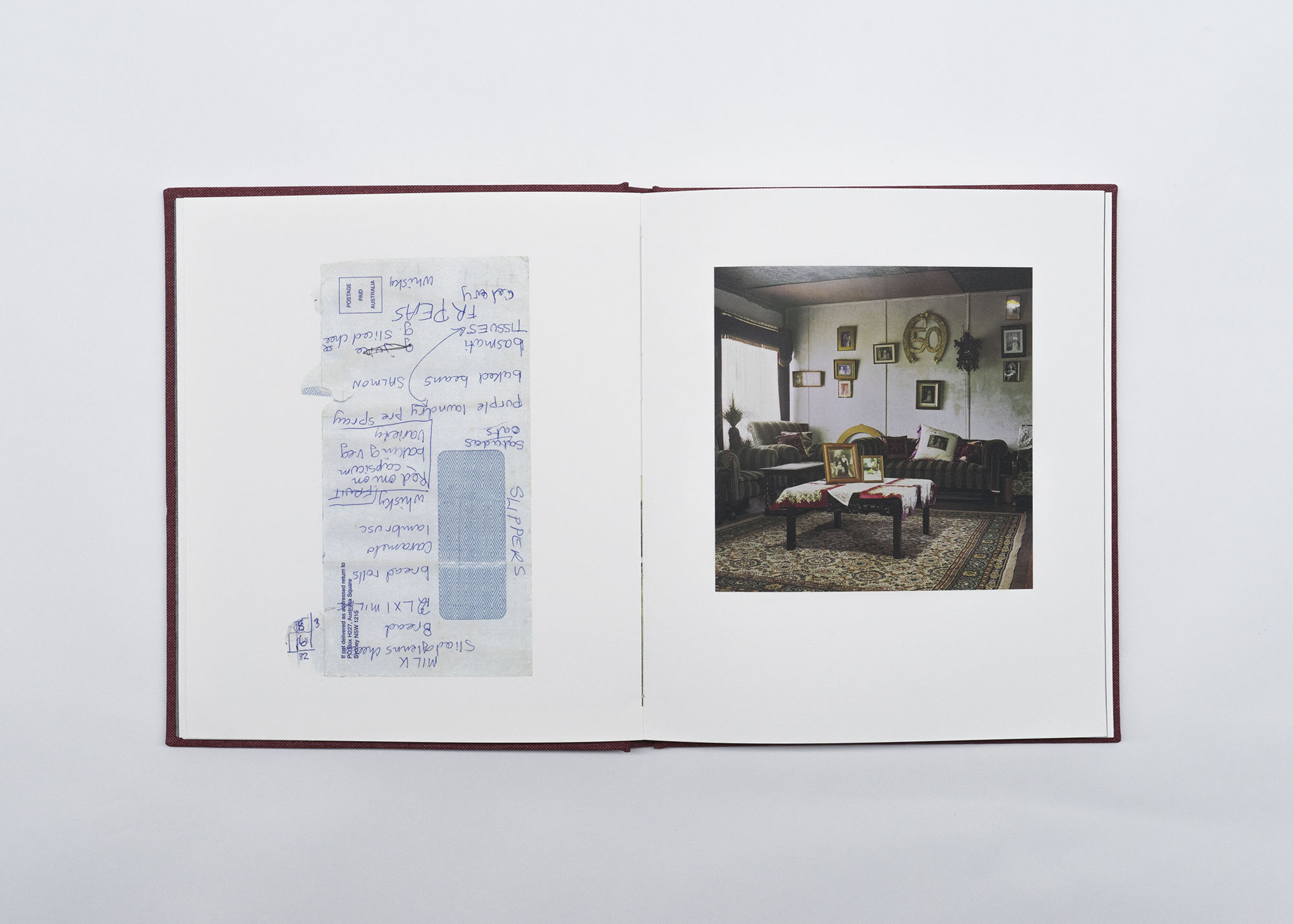

The Moat paints French Island as quite desolate; it is a portrait of a place with a vast, rugged landscape, yet we are slowly introduced to snippets of life on the island – scans of handwritten notes; empty dance halls; dusty, beat-up cars. It feels as though time has stood still. What was your intention in portraying the island in this way?

French Island holds an almost enigmatic status in the eyes of the locals in neighbouring areas, with many viewing it as possessing an unnerving peculiarity. Without straying too much into clichés, when you arrive at the jetty you are hit with this feeling of entering a different world which is difficult to describe.

The title for the project, The Moat, is a reference to the geography of French Island and refers also to pride and cultural protectionism that betrays an uncomfortable wariness of the island’s fragile autonomy. There is no local government funding allocated to the island, quite simply because there isn’t a local government, so it effectively governs itself. The few communal facilities that do exist (a cricket ground, community hall, one general store and a network of dirt roads in-between) are paid for and maintained out of community spirit.

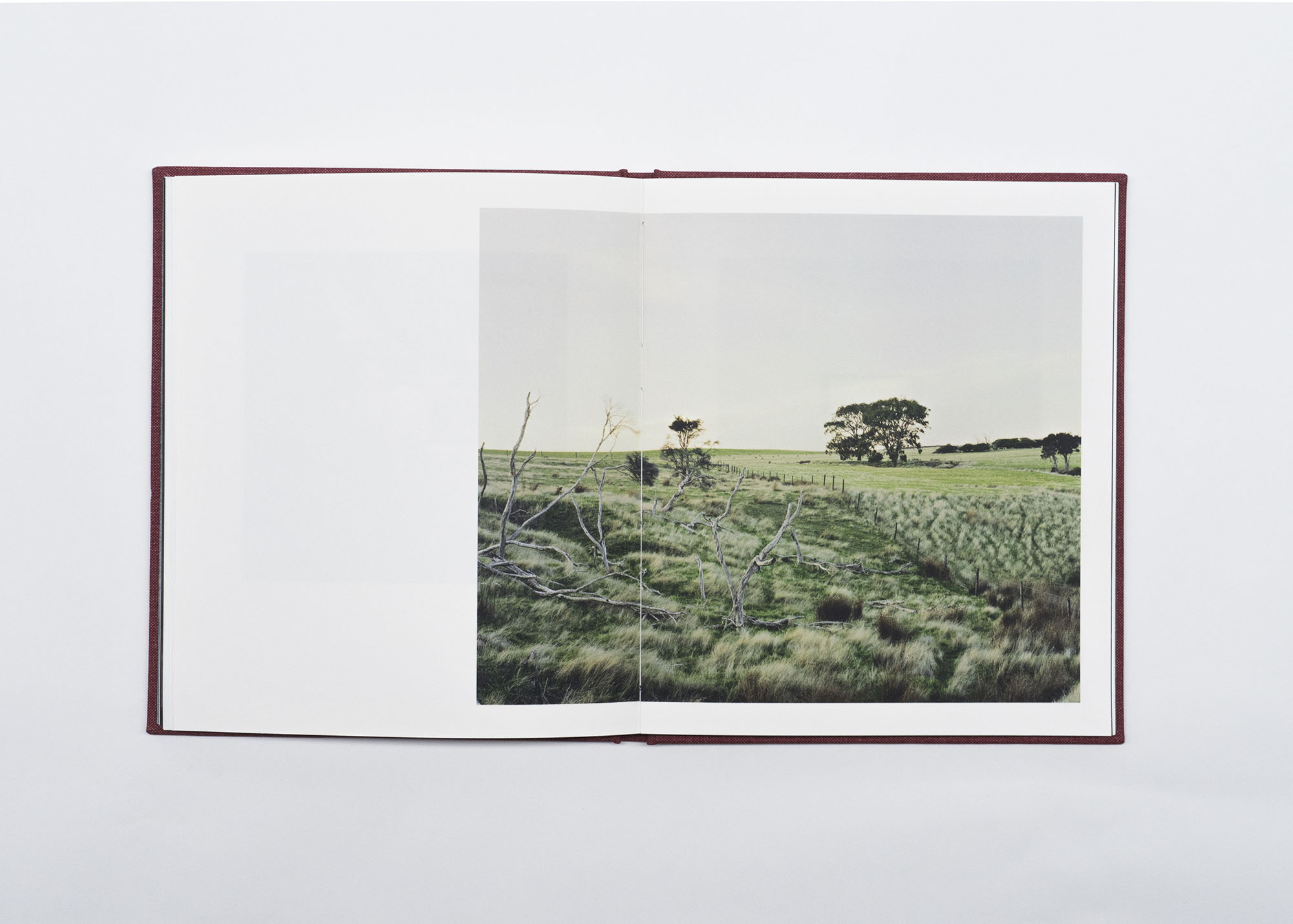

It is a vast and at times unforgiving place, and although European Australians have been able to carve out an existence on the island there is still an understanding that you’re at the whim of the island’s environment. It’s an understanding that you’re never fully in control, and for that reason I wanted the book to be as much a portrait of the island as it is of its inhabitants. I wanted to portray it as being a pensive and untamed place, as though the people who had settled there had not wrestled it into submission as much as they were at its mercy. It represents to me a sort of tension that exists between European settlers and the Australian landscape which permeates rural Australian culture.

French Island is disconnected from many regular necessities such as running water and electricity, however, still maintains a small population. The portraits we do see are of people from a lower socio-economic background; which you’ve described as drifters and dreamers. What methods did you employ to ensure the integrity of your subjects in your portraits?

The island is home to a wide range of people from varying economic and cultural backgrounds; however, the harsh environment instils a culture of frugality in the community which I think is more representative of what life on the island is like than that of the island’s demographic.

Much of my time was spent reconnecting with what the island meant to me, so naturally the portraits I took were in some way a projection of my understanding of the place. Many of the subjects in The Moat are friends that I made through my time spent on the island; I very rarely photographed someone that I hadn’t spent considerable time with, as I felt that the lack of familiarity made things feel less collaborative.

I would also take prints of my photographs, book edits, and ideas I had jotted down along to community events to ask for feedback. Sometimes they were elated and were full of praise, other times I was put in my place and reminded that my knowledge of the Island was not as thorough as I thought. It was difficult at times, but this process was vital for me to incorporate a more pluralistic narrative into the book that was more than just my way of seeing.

Throughout the book are full-bleed, black and white images of stills taken at night of various wildlife, which sits in contrast to the rest of the book. What do the wildlife represent and why was it important to include these stills?

The vast majority of French Island is made up of bushland, with a few arterial fire access tracks carved through the landscape that are only traversable in summer when the sun dries the Island to a dustbowl. During these summers when I was photographing for The Moat, I would spend entire days exploring out in the National Park without seeing another person.

I would, however, be constantly running into motion-activated game cameras that were staked out in the bush in the middle of nowhere. Every time I ran into one, it would take a picture of me. I would be roaming around, completely absorbed in my surroundings – and then all of a sudden, I would turn around and realise I was being photographed.

I couldn’t shake the feeling of having been violated every time it happened. I think what the cameras did was make me feel like an outsider, which was an uncomfortable realisation given how potent my love for the place was. For a fleeting moment, they reversed the power balance of me being the person holding the camera.

As it turns out, these cameras are stationed all over the Island (some 300 of them) as part of a program to monitor and track the population of invasive animal species that had either been introduced or found their way there themselves. I felt that the surveillance aspect of this program weaved into the concept of the book title particularly well, and I was very fortunate that I was granted permission to use them in the book.

There is a piece of text early in the book that I wrote which reads: “It is said that deer once swam to the island at low tide in search of food. When the water returned, they were stranded there – victims of their own curiosity.” This sentence represents to me a dialogue that I was having with myself about my connection to the Island, and how French Island is a sort of microcosm for exploring the role of postcolonialism in shaping the cultures and attitudes of rural Australia.

Did you always envision the project in book-form? What was your experience of self-publishing?

Studying photography instilled a fascination with photobooks, so I suppose it was inevitable that my first major photographic project would end up in book-form. The tactility of a photobook, and how it possesses the power to become a sort of artefact is what drew me to the form and why I chose to present the project this way.

Self-publishing for me was a bit like lining up for immunisation at school; much more daunting in my head than in reality. I was very fortunate to have the support and direction from my tutors at Photography Studies College and my mentor, Ying Ang, to coach me through each step. I also had the privilege of attending a photobook workshop with photobook designers Teun van der Heijden and Sandra van der Doelen, which enabled me to avoid a few of the design roadblocks that I think a lot of photographers run into. Still, though, there were a lot of nights spent editing until 5 am.

View The Moat in full at the Australia and New Zealand Photobook Award.