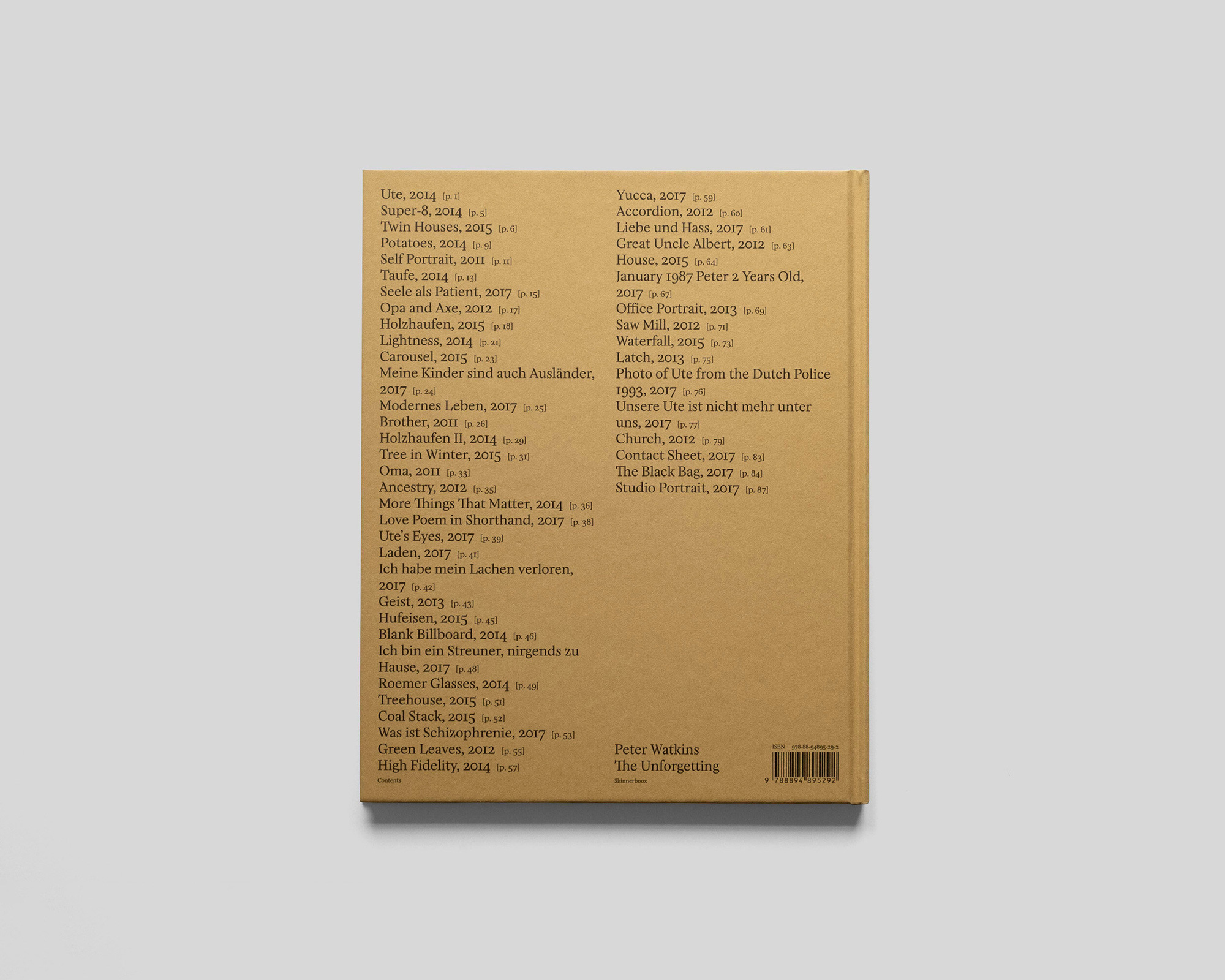

Peter Watkins – The Unforgetting

I think the pain of loss is something that never really leaves you. If you have experienced it young there is a certain shift to the way you think about life, and you consider questions of mortality too young. I think I’ve approached it with a willingness to understand something that has oftentimes been difficult, but everyone deals with mourning in different ways.

The Unforgetting is Peter Watkins’ long-term exploration of trauma, loss, and shared familial memory, all woven together within a series of photographs, sculpture, installation and objects. As the recipient of the 2019 Skinnerboox Book Award, The Unforgetting photobook was launched on the river Seine during the opening evening of Polycopies in November of the same year, as well as being selected by Sean O’Hagan at The Guardian in his end-of-year Best Books of 2019 list.

The work has been through several physical permutations as it has grown and expanded with each exhibition, but the book has encouraged a closer more intimate reading of the work that brings a sense of closure to the endeavour that has spanned almost a decade. Watkins has won several accolades and nominations over the years for his work on this project, including two Paul Huff Award nominations, a Magnum graduate award, and more recently, has been shortlisted for The Author’s Book Award at this year’s edition of The Rencontres d’Arles.

During his installation at Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery (2016), Watkins sat down to discuss the project with Pauline Rowe; a freelance poet, writer, and tutor with an interest in mental health and social practice. This adapted version of the conversation published here is printed in a separate booklet found in the back pages of the book.

Pauline Rowe: As children, we’re given received versions of someone’s life and death, which is generally not to be questioned. Would you say that The Unforgetting is challenging this in its presentation of items of evidence—evidence, I mean, of your mother’s life?

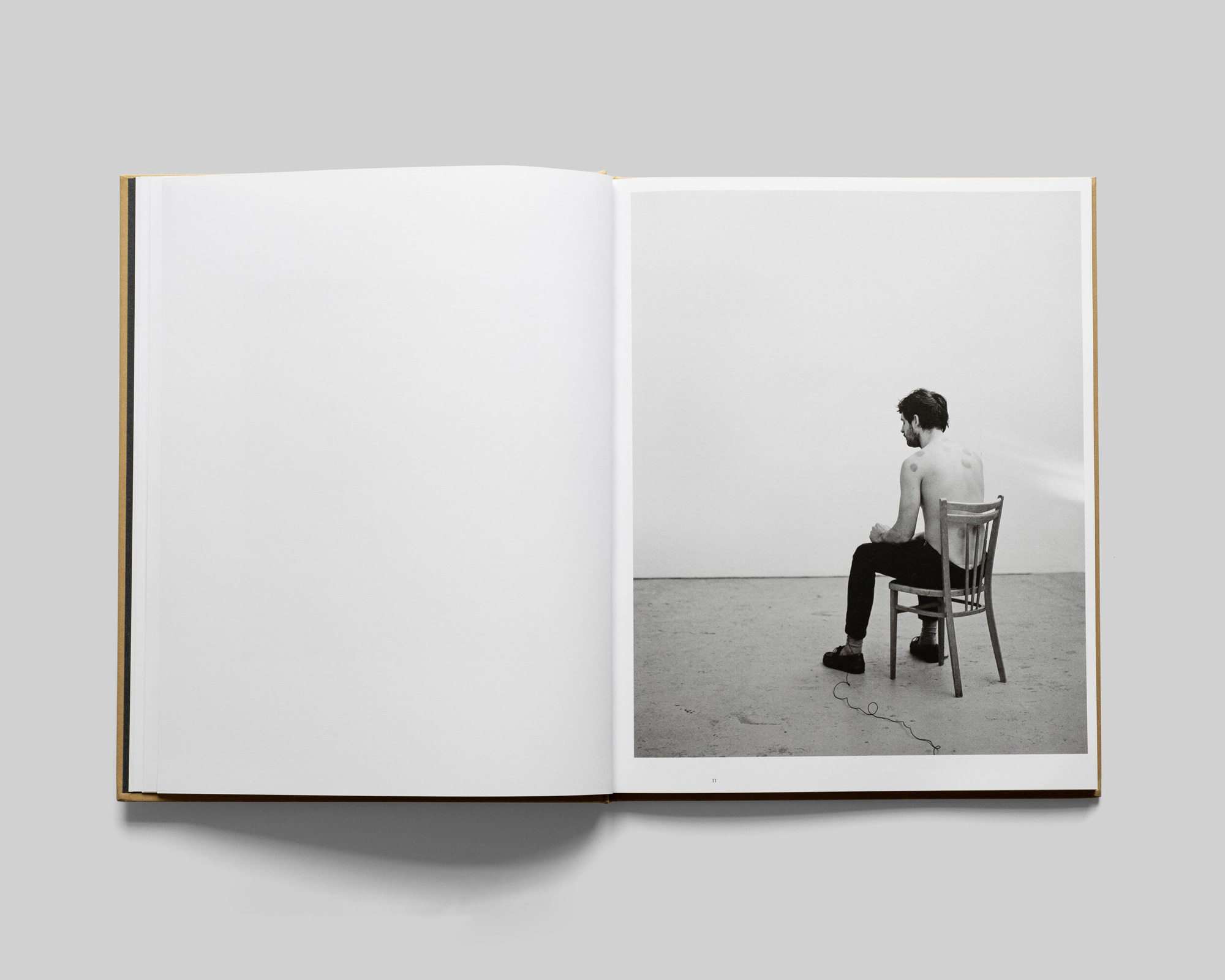

Peter Watkins: To an extent, I think I was looking to substantiate my mother’s life in some way—to dedicate the necessary time to understand something of my family’s shared history that has been at once very present in my life, yet throughout my childhood was a source of deep repression. In that sense, The Unforgetting is about taking memory as a starting point—my memory, and those communicated to me by my family—but reassessing and reconstituting this memory through objects, documents, and creating staged situations. This process rests somewhere on the fringes of a ‘documentary’ practice and something more metaphysically oriented and difficult to pin down.

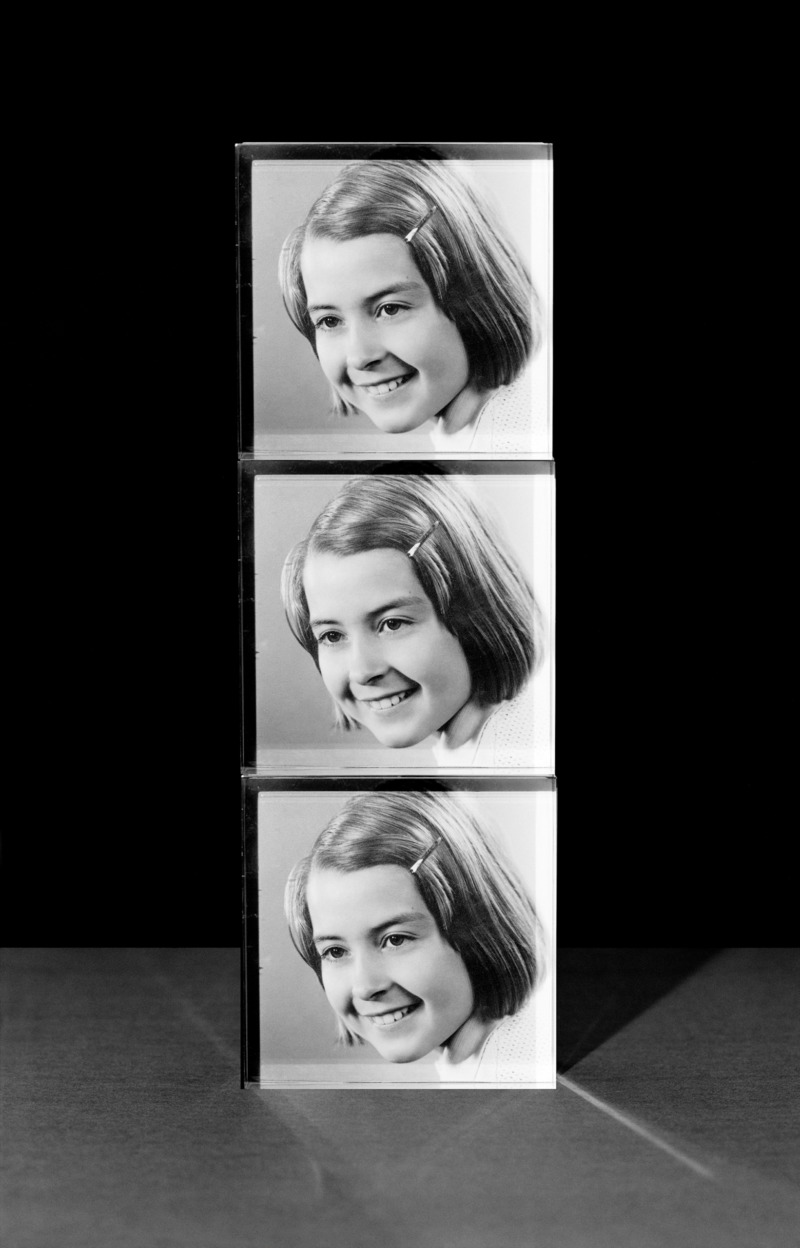

Early on in the process I interviewed my family, and came to realise that the series of events leading to my mother’s death had been in some sense reduced to a straightforward narrative, as if the ensuing years had stripped away any sense of complexity and depth or accuracy, and had been replaced with a few factual occurrences and a good measure of reverence for the dead—the kind that is almost always afforded to those who die young and in tragic circumstances. My memories of her manic episodes before her death far outweigh any other memory I have of her, and so in a way I’ve been trying to come to terms with the trauma of this experience. The objects have this totemic, monumental quality about them, and I think because they have been isolated, abstracted from a greater whole, and re-imagined as photographic representations, they take on this heightened sense of purpose, and we are invited to meditate on them as such and look for connections in the spaces between the images. They are evidence of lived experience, things that remain of a person, but they obscure as much as they reveal, and speak universally, rather than with a sentimental, overtly personal tone.

Walter Benjamin described aura as a thing’s ‘unique existence’ and wrote that the aura of an object is stripped away by the photographic representation—the object loses its uniqueness in the face of potential innumerable reproducibility. But through the transformation of object to representation the resultant image also has this inherent connection to time, to place, the specific moment or situation that it was created in—that is irrevocably lost to the past. So, in this sense the object is not only lost in the act of transformation, from object to representation, but the moment is forever lost, along with that object. In this way it can be a mournful act to photograph an object, and the representation becomes something quite different to the object itself.

For each of us, there is importance in finding our own stories or narratives that make sense. Do you feel you can’t make sense of your story fully because you’re compelled to search after something unanswerable?

I think that there is so much that is unanswerable when you go out in search of some form of truth or authenticity in your past, something that I think we all feel compelled to do at some point in our lives. To make sense of the past is to attempt to ground our lives, to afford them meaning and a sense of deep-rootedness, even if that search proves to be painful. These stories and narratives that are passed through families are just that; they’re stories. They have narrative arcs and moral punch lines, passed down through generations in a way that builds a foundation of meaning that justifies our experience and offers purposefulness. I think with this work I was holding these narratives to account somehow, even if this is not perhaps fully evident from the works themselves. There is a futility in making sense of your story, and a delusion in searching for truth. What I’ve made is an abstraction, it doesn’t capture the essence of my mother, or my wider family history, but looks at that which can’t be fully grasped, which lies somewhere in the space between fact and what is only partially remembered; a kind of forced remembering.

When a parent dies, there’s a risk of secrets and silence. Has this been important in your formation as an artist?

I started working on The Unforgetting, or earlier iterations of the project, shortly after my father passed away, so yes, the possibility of never finding out about my past became a very real possibility. It suddenly felt like something that was really urgent to me as I came to realise that we had never talked about what had happened to my mother, about this shared experience. I read somewhere that the sudden loss of a loved one can spark in us the repressed memories of a past loss, and that instead of focusing on that immediate loss, we look to the deep past, to that which we failed to come to terms with previously.

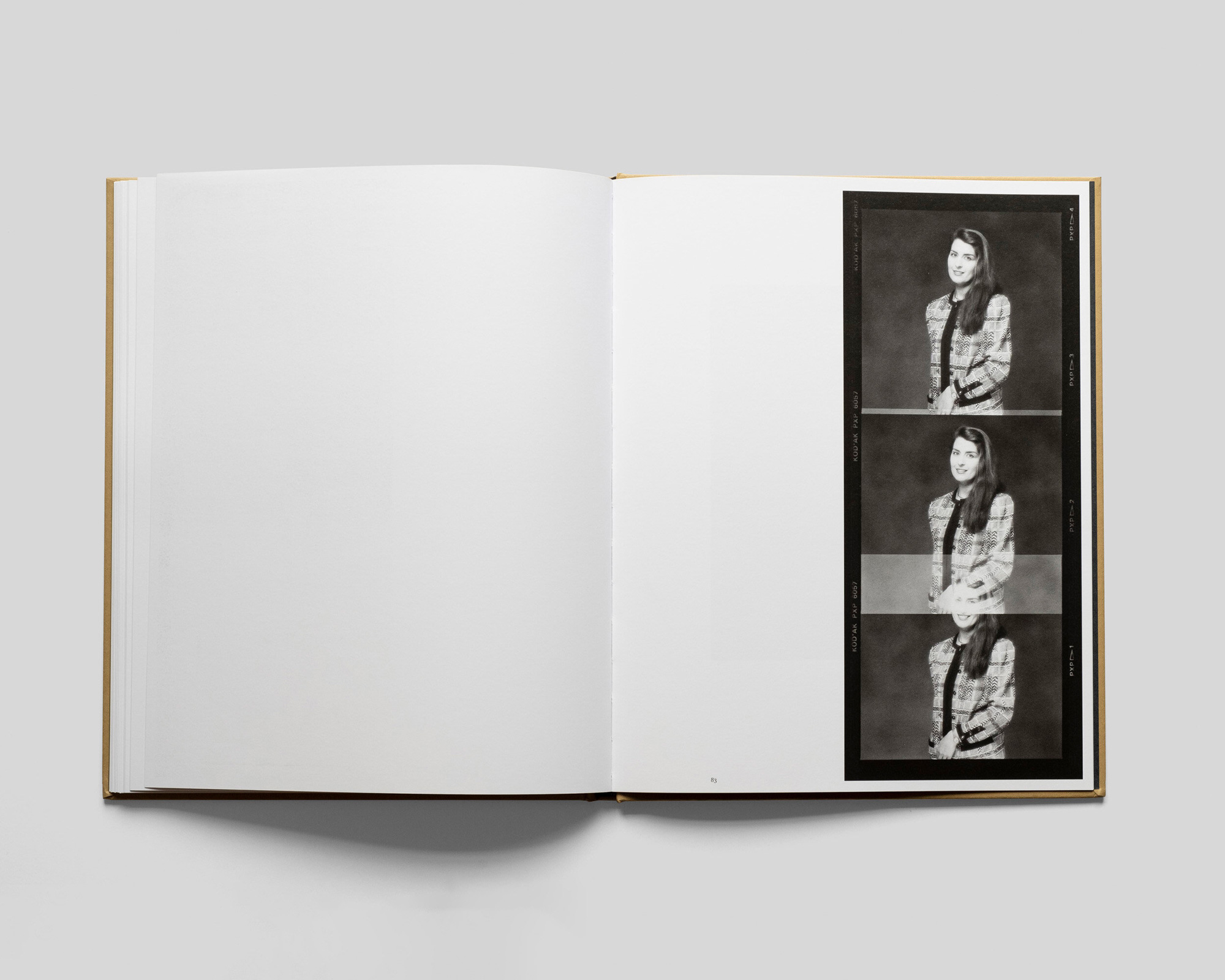

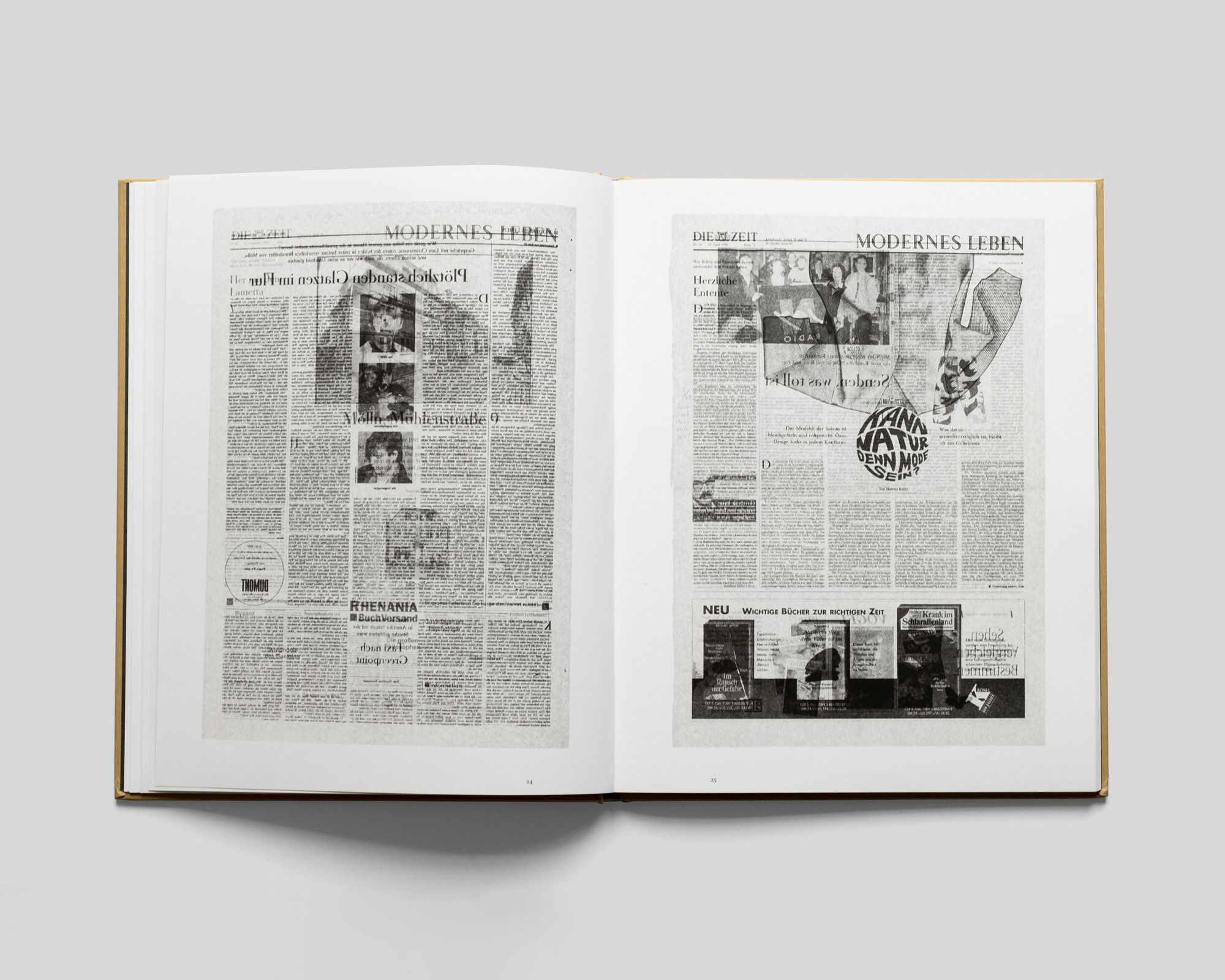

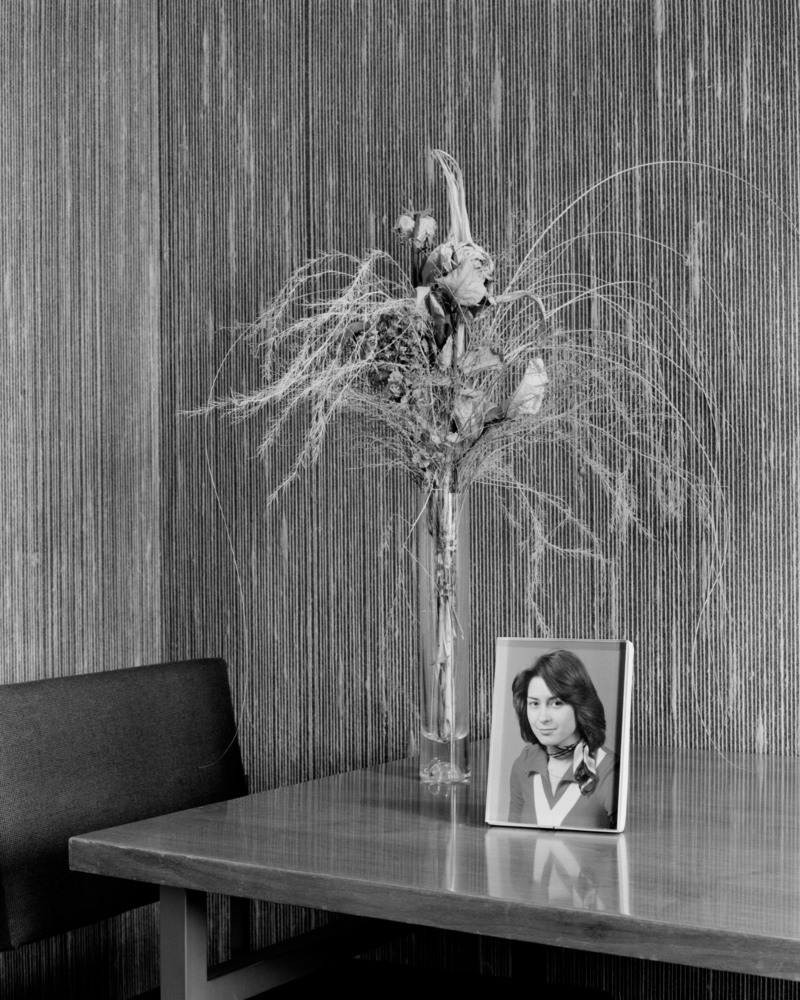

My grandmother has been the archivist of the family, and her house has a museum quality about it and had always given me that false sense of unchanging fixity. She has kept everything of my mother’s exactly as it was and would archive everything, from her achievements, photographs, to newspaper clippings that reminded her of her lost daughter, each annotated on the spine explaining why the article had triggered some memory in her, often unwittingly forming image-text relationships. All the work apart from Self Portrait (2011) was shot in the village where my grandmother lives, in the house where my mother grew up. I would convert her old shop, which was at the front of the house, into my studio when I’d go to visit, and then create these object assemblages from the things that she kept, shooting mostly at night. You see the shop windows and fabric curtains from this room in a couple of the photographs.

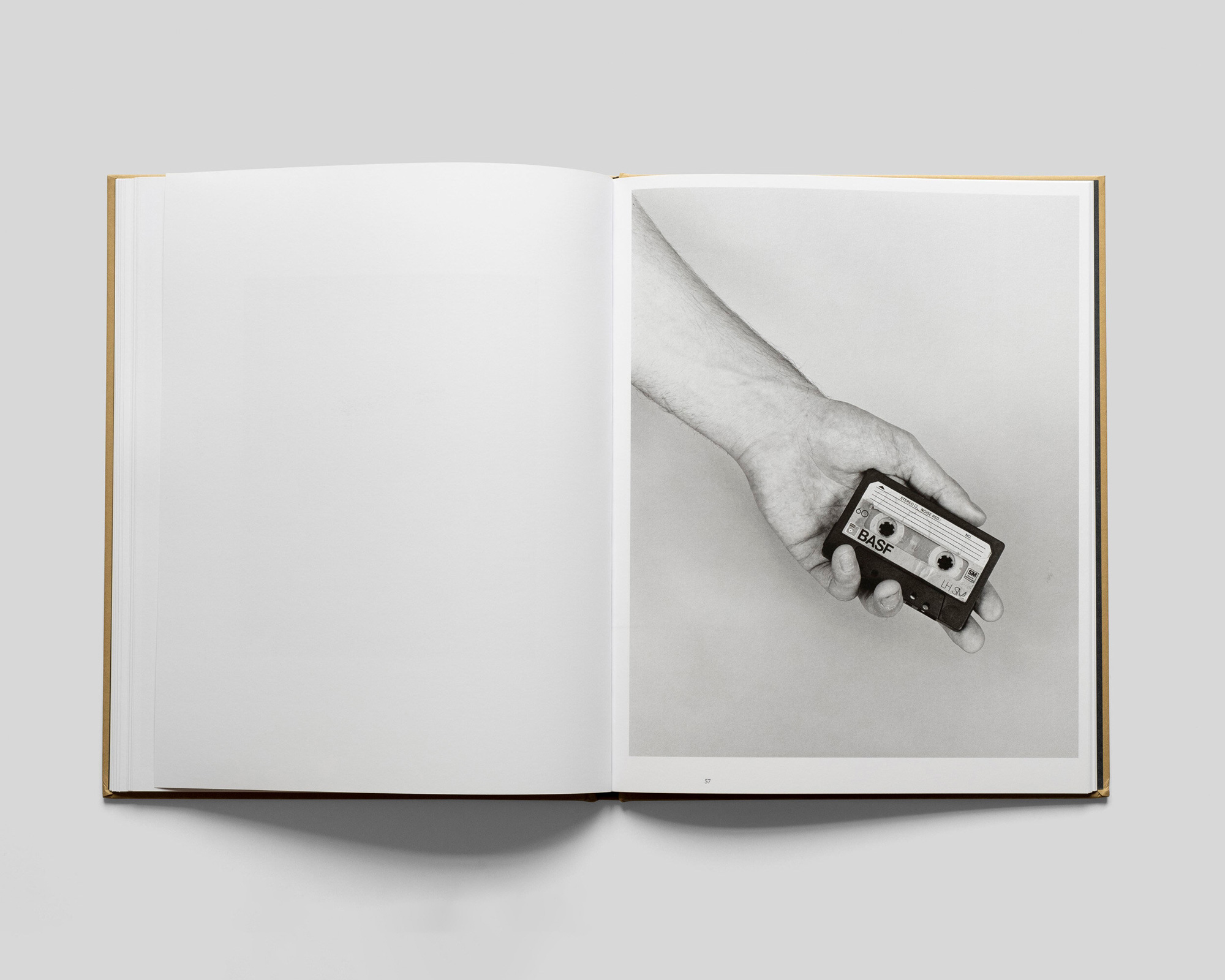

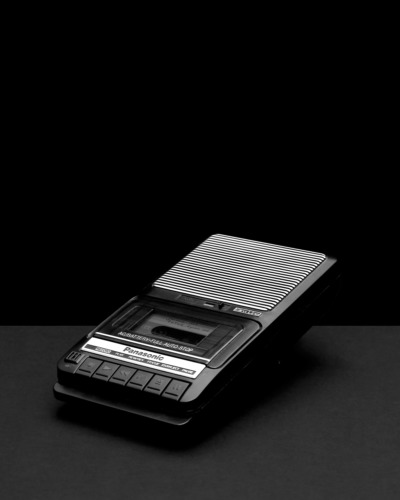

The objects depicted suggest that one important aspect of life is sound or music (the accordion, the tapes, the audio cassette, which again suggest evidence, something to be replayed and heard). Can you comment on this?

There are layers of narrative hidden behind the images. The accordion, for example, was my grandfather’s, and the story goes that he was playing in some group, and that’s how he met my grandmother. The rolls of Super-8 film contain moving images of my mother and family on various holidays in the ‘60s and ‘70s, invariably smiling, happy, bathed in sunlight. The still-life image became a way to conflate all of these images into a single, unified one, albeit withholding somehow the image of happiness. My mother was a linguist, and she used to teach herself languages by recording her own voice on a Sony tape recorder from the early ‘80s, carefully recording the words and phrases she was practising, and checking back for good diction. She would sit cross-legged on the dining room floor with the tape recorder between her legs and practise. The tape I photographed was actually a mix tape that she had made, and left in my grandmother’s car, and as the radio never worked, this became my soundtrack to the project. Another tape I have is of me, at two years old, singing nursery rhymes with my mother, the only recording I have of her voice.

January 1987 Peter 2 Years Old, 2017

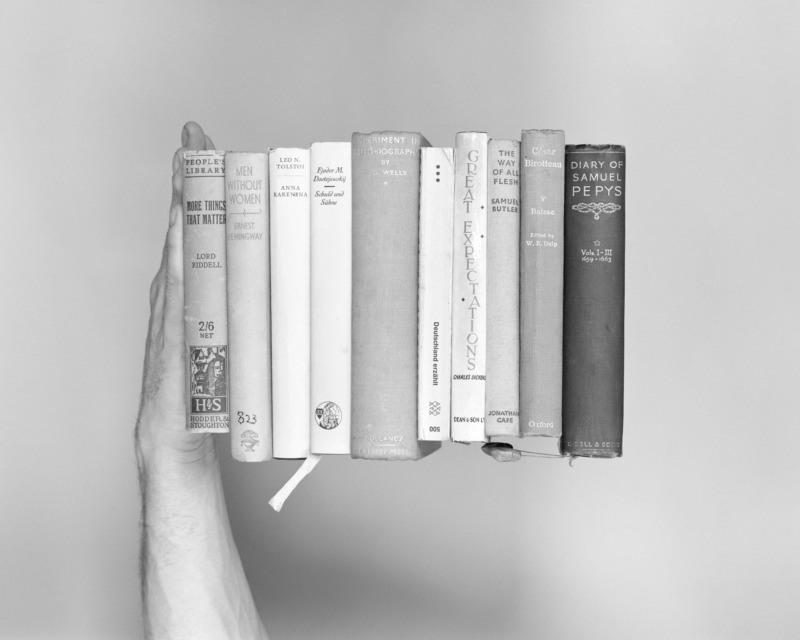

Another important aspect of life here is shared history, warmth (the wood), drink, books, stories, the forest. Does this mean for you that the necessities of life include cultural matters as well as the family archive, other photographs?

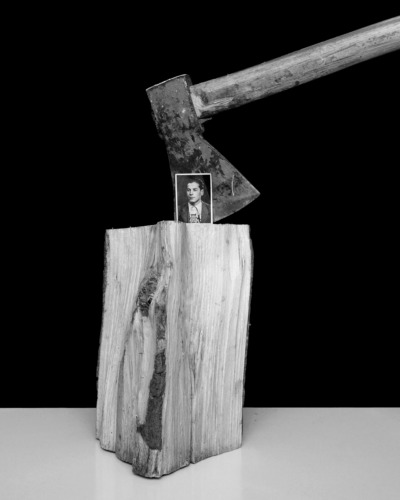

… About wood, about this idea of shared history, the glasses, the forest? The glasses are called Roemer glasses and are a traditional German wine glass, (they have a coiled green stem, topped by a clear bowl, and are called Roemer as a tribute to the Romans who brought wine grapes to Germany in the 4th century) and the inscription carries the name of my grandfather. They were given to him for each year’s full attendance of choir practice, something he kept up for much of his life. Each glass represents a milestone of time. He is also pictured as a young man in a small photograph rested against the blade of an axe. He passed away during the course of this project, but one of the last things we did together was to chop firewood, and I had a sense at the time that this would be the last time we would carry out this repetitive, masculine activity together. I filmed the whole thing and took a log away which appears in this exhibition cast in concrete and is repeated three times. Wood is repeated throughout the project. For me, it speaks of the folkloric, of Germany, of this German sense of ‘Heimat’, but also of the passing and splitting of time. In the photograph of my brother suspending a large piece of beech wood for the camera, the wood appears to flow from his arm, and there is a certain liquidity to the image, or sense of suspension, which I think is echoed in the photograph of the baptismal dress, and the books.

Did the making of this collection feel like an honouring of your mother? And what do your family feel about it? Have you been able to respond differently as a son/brother to bereavement because you are an artist?

I think the pain of loss is something that never really leaves you. If you have experienced it young there is a certain shift to the way you think about life, and you consider questions of mortality too young. I think I’ve approached it with a willingness to understand something that has oftentimes been difficult, but everyone deals with mourning in different ways. I think as more family members have passed away, I have unwittingly become the family archivist, although my approach is from an artistic standpoint, and not how you would traditionally catalogue a family history.

Is this an archive of memory, then—an attempt to understand more about yourself in relation to loss?

I suppose it’s an archive of sorts, but I don’t really think about it strictly that way, although it does obviously make references to certain display methods used in museums and does tap into the archive, but I was very careful not to include too much information, or rather careful about how much was out there. ‘The Black Bag’ and the ‘Letter from the Dutch Police 1993’ are the only actual objects on display in the project and come to stand as a kind of dark star around which the rest of the works revolve. Their significance is made more prominent by their selection ahead of the multitude of other things. Supplementary information such as this interview, or articles that have been written about the work, can always be looked at to offer an expanded experience of the work, to peel back some additional layers, but really, I’m more interested in what the viewer can bring to the experience. It’s very personal work, and I’m hyperaware of the fact that I’m putting it out there, so I have had to be careful about how much personal information gets out into the open.

What lies between these images seems so important. Do you know if they have helped other people to approach loss or grief in a different way? Would that be important to you?

I think I touched on the space between the images in some of my previous answers: how there is space for connection, and how the works stand to reinforce one another and make one another stronger and have an implied narrative that is completed or reinterpreted by the viewer.

People do write to me from time to time, when they have come across the work or read about the project, and tell me how they have related to the work in terms of their own experience, and they often tell me things that have happened to them. These correspondences seem to always come out of the blue, and you only then get this sense that the project is out there in the world, and that there are people who attempt to relate to such things. Mostly, though, people seem to wonder whether carrying out the project has helped me in some way to come to terms with my past and my place in the world, and it’s something that I guess is forever an ongoing process.

Unforgetting is very different from remembering—it feels like a hard-won fight. Would this be overstating the difference between the two for you?

Chris Marker, the late filmmaker and artist, wrote: ‘I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting but rather its lining’, by which he was in part referring to how memory is not something that is fixed, that it is always subject to change and reinterpretation, much in the same way as history is subject to being rewritten. The more you dig into memory the more it seems to move away from those seemingly pure flashes of memory that we hold onto from childhood. The image of my mother became irrevocably changed once I started to dig into the past and into my memory.

Can you say something about the christening gown?

The christening gown was something that came very late in the project. When I thought I had sifted through everything, my grandmother pulled out the dress, along with a lock of my mother’s hair from a cupboard. The dress is pale yellow and is photographed in black and white, seemingly impossibly suspended in front of a fabric net curtain, in the makeshift studio where I shot most of the work. The dress appears to float weightlessly, and perhaps has that feeling of liquidity I mentioned earlier. The circularity of the baptismal act and my mother’s death by drowning is perhaps what drew me so magnetically to the dress. The photograph is framed behind yellow glass, and here I was really thinking about the idea of putting colour back into the work, and about the falsity of artificially putting yellow back into the dress—the strangeness of applying this wash of colour over the piece. Yellow is the colour of warmth, of light, and colour brings with it emotion, whereas black and white can signify a more evidential, calculated approach to working. But yellow is also the colour of decay, of death, of the hallucinatory space in the mind, and of dreams. The work is uniformly monochromatic, so when colour comes into the work it introduces colour to all the work—but it’s a false colour, something applied to the work after the image has been made.

All image courtesy the artist and Skinnerboox. The Unforgetting can be purchased here.