Rebecca Jagoe & Louis Porter – Hands

“Asking for a hand is the entrance into the female body, the touch of a hand frequently the first touch between lovers.”[1]

—

It began with a meeting on a hot day. He was running late; I was waiting outside the front door for a while. He arrived panting slightly, a sheen of saline across his forehead. Sorry, I had to jog from the car. I held out my hand.

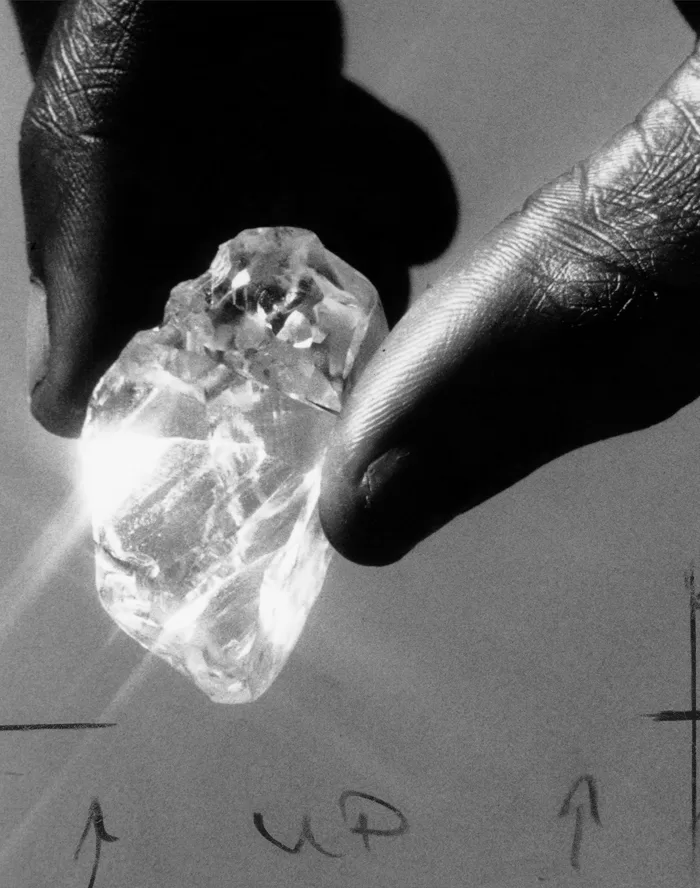

The exchange of bodily fluids should belong to the domain of intimacy, surely. Yet here, on this sweltering afternoon in June, this formal gesture resulted in the cross-contamination of sweat, palm to palm.

Sorry, he said and wiped his hand on the pale grey trouser leg, a dark smear left behind. My hands are really sweaty.

There was only one thing worse than this soggy handshake, and that was the acknowledgement of its sogginess. A further dampening of social relations. I smiled wanly.

And yet, unlike so many other handshakes, this greeting has lodged itself in my mind and refuses to be moved. I can still recall the feeling of clammy flesh beneath my fingers, the grip that was slightly too tight. At first, I was repulsed by this man; angry that he had violated a social norm with his bodily effusions; I wished to put the incident out of my mind. Yet now I find myself returning to this moment compulsively, perhaps as one returns to a bad smell. Something happened this humid afternoon, something that disturbed me on a level deeper than I had anticipated. I must determine why.

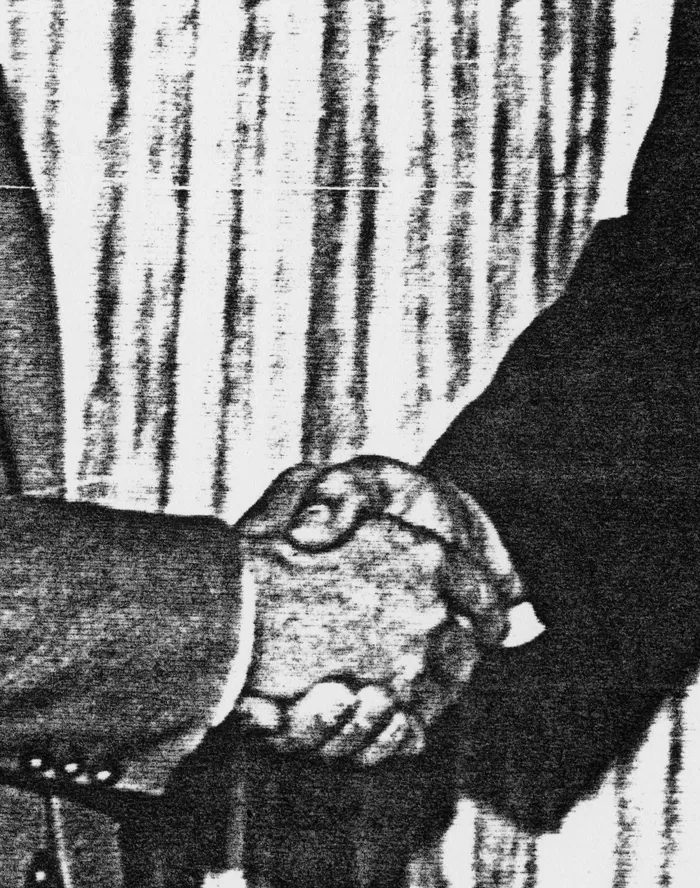

The exact origins of the handshake remain veiled in mystery. There is evidence of its use from at least the fifth century BC. General consensus holds that it was a gesture of peace as the symbolic laying down of arms: neither party can hold a weapon and enter into the gesture.

Today, of course, handshakes are no longer limited to a truce. The handshake can be contractual / a greeting / to mark a beginning / to mark an end. However, fundamental is that it still remains in the realm of the symbolic.

It is the touch equivalent of asking: How are you? at the beginning of a conversation. In a different conversational context, with different intonation, these words can be the opening to an outpouring of ecstatic or grief-stricken exclamation. Yet as a polite greeting they are asked more or less without sincerity.

I imagine, though I cannot recall, that the estate agent–whose importance in this piece is so fundamental I shall henceforth refer to him as He. But where was I. I imagine that He said to me, Hi, how are you? to which I am sure I replied Fine, how are you? I did not launch into a detailed account of my current state of mind: such a reply would be an excessive intimacy and as such, inappropriate. These social niceties are meaningless of content, the symbolic exchange of words. Thus I have entirely forgotten them. But the handshake, the handshake remains.

I did not reach out to touch His hand through a desire for close physical contact with this man. I did not see his hand and feel drawn to it, though I recall now it was an exceptional hand. Long fingers and square nails, a broad palm and smooth skin with a trace of hair around the wrist. Large, but not too large. I could tell he would know what to do with his hands. But I digress.

I did not reach out to touch His hand through a desire for close physical contact with this man.

As I held my own hand out, I was anticipating an exchange that followed the conventional rules of etiquette:

- Look at the hand you are about to shake. Missing it is unbearably awkward.

- Hold the hand of your greeter, but do not squeeze it.

- Shake three to six times, moving from the elbow: firm, but not aggressive.

- Once you have finished shaking, withdraw your hand and do not linger.

Despite the excessive lubrication, His handshake was – happily – the perfect level of firmness without aggression. I say ‘happily’, for there is a strange value placed on the firmness of handshakes, as though physical strength were a suitable yardstick for character. In fact, this notion of a strong handshake as a marker for character is so intrinsic in social relations that this entire paragraph is beginning to feel like a redundant overstatement. Yet the paragraph persists: no, I shall not delete it. For while the symbolic value of the strength in gesture remains standard, this does not make it any less bizarre. It is as though when meeting, two people would enter into an arm wrestle: the age-old and archaic phrase MIGHT IS RIGHT springs to mind. Softness is a weakness. How very primitive.

Yet I wonder what else a softness of touch across fingertips could provoke.

“The utility of the handshake as overdetermined and unstable signifier is, I take it, manifest and obvious: on the one hand, the “manly” handshake and the “fraternal” embrace” are respectable, disciplined, and sexually innocent gestures of male sociality (imagine, for instance, counting the handshakes in Dickens); on the other hand, such gestures, given a slightly altered social context, readily take on the heat and pressure of the sexual.[…] Consider what happens when fingers wander”[2]

I return to thoughts of the sweaty handshake between myself and Him, and the discomfort felt between us. Two bodies coming into moist contact on a hot day, his skin pressing against mine. Perhaps my hand is an entrance into my body and likewise his own. Bodily fluids intermingle, his fingers probing my own. Interiority meets interiority, they press against one another across a membrane that is porous and fragile and invades and is invaded. Firmness was essential as a means of retaining some residue of a determined gesture. If there had been any softness of touch, had his hand stroked mine with a teasing lightness, had I run my fingertips across the line in his palm and then his thumb had started to move up my wrist. But I digress.

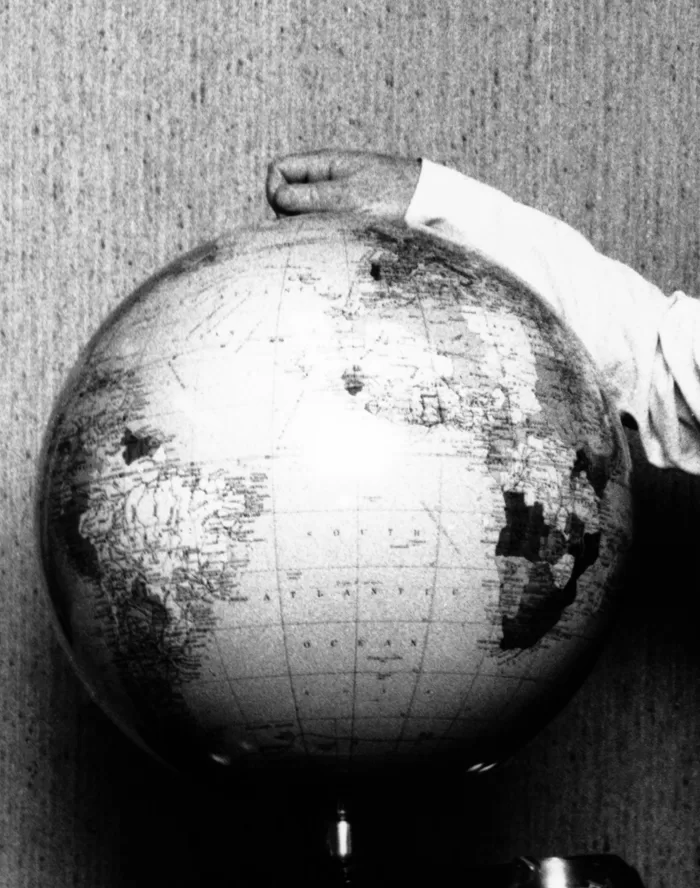

Hands, devices for pressing, pushing, reaching outwards, hands grasping and clawing out of the confines of social etiquette. Hands reach outwards but receive information inwards: that afternoon, upon entering into the handshake I was opening myself through the hand: the palm becomes another orifice. The hands are a doorway, an entrance point to interiority and a means for interiority to reach out and form contact with exteriority. Even when they are not literally sticky, sticky with sweat, His sweat; even when they are not literally sticky, perhaps the hands always maintain this stickiness of an uncertainty regarding boundaries.

As He turned to lead me into the house, I looked at my hand smeared with the grime of his body. I smelt it, I ran my hand under my nose and across my mouth and caressed my own face with it. I put my finger in my mouth. Perhaps he did not know it, but through sweat, a part of him had probed into me.

[1]

Michie, Helena ‘The Paradoxes of Heroine Description’ in The Flesh Made Word: Female Figures and Women’s Bodies (oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987)

[2]

Craft, Christopher ‘Descend, Touch and Enter’ in Another Kind of Love: Male Homosexual Desire in English Discourse, 1850-1920 (California: University of California Press, 1994) p56.

A Few Palm Trees is an ongoing experiment in photography and literature, edited by Joanna L. Cresswell for Paper Journal.

Each month, a collector is invited to select a set of images for a writer to respond to.