Studio Visit: Ewen Spencer

Beginning his career working for seminal publications such as The Face and Sleazenation, Brighton based photographer Ewen Spencer quickly garnered attention for his editorial work focused on youth and subcultures, notably his documentation of the Grime scene with his 2005 series Open Mic. With a solid body of work behind him, came commissions with clients such as Sony, Nike, Last Minute, T-Mobile and more.

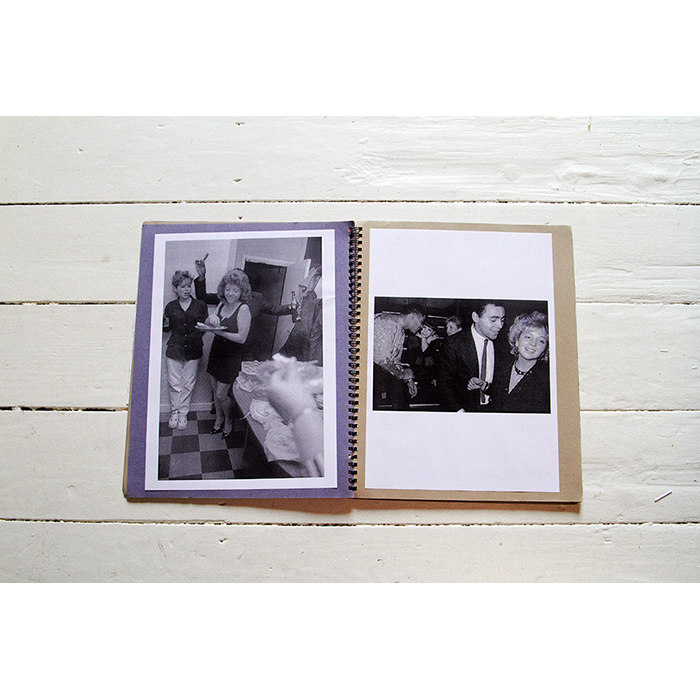

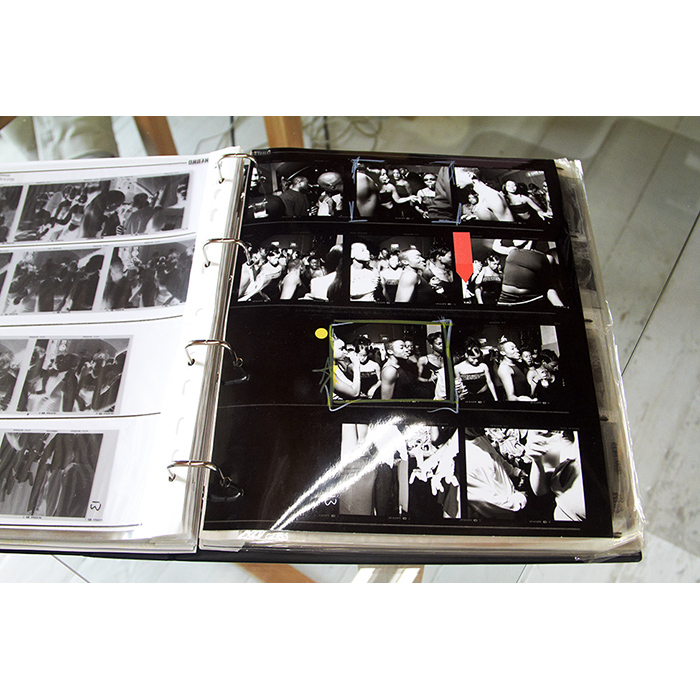

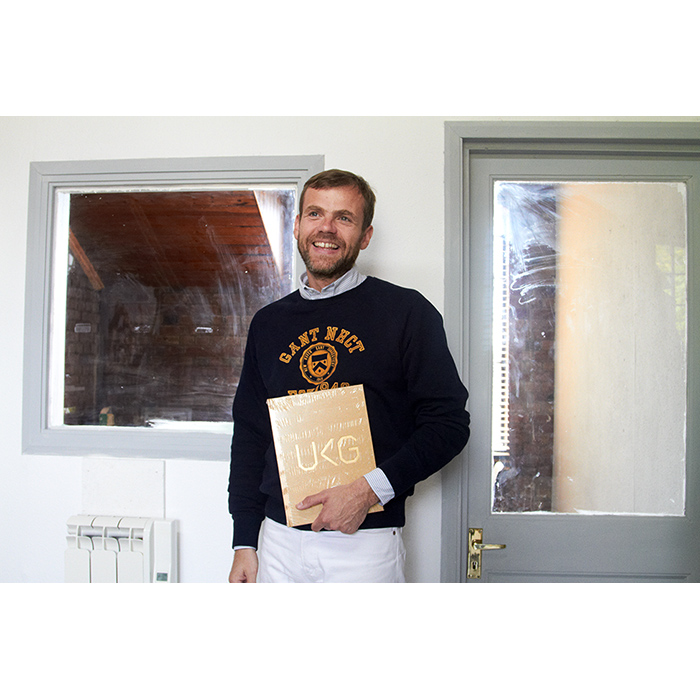

Ewen’s recently published photobook UKG (GOST, 2013) documents the early days of the UK garage scene, which lead to him directing the documentary Brandy & Coke, commissioned by Dazed magazine’s Music Nation series broadcast on Channel 4 earlier this year (scroll down to view). We headed to Brighton to spend the day with Ewen and his Studio Manager Harry Watts in their studio, read on for more…

Where is your studio and how long have you been in the space?

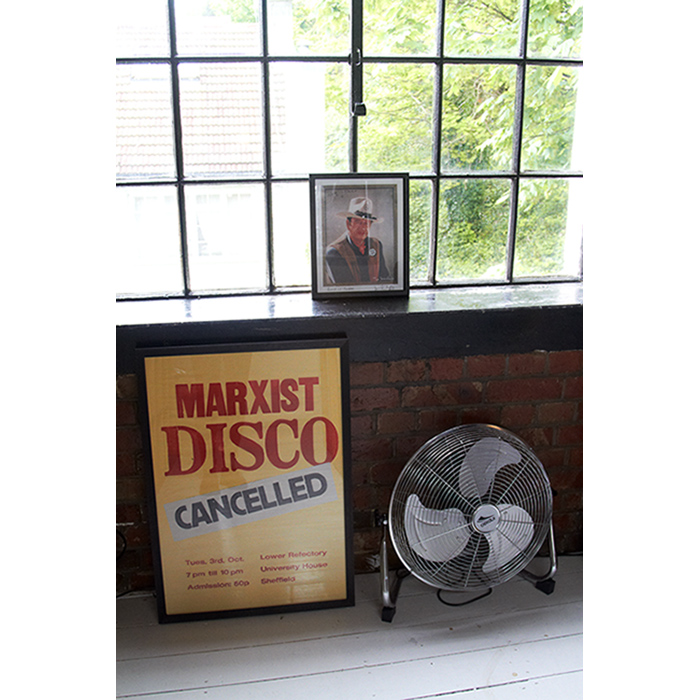

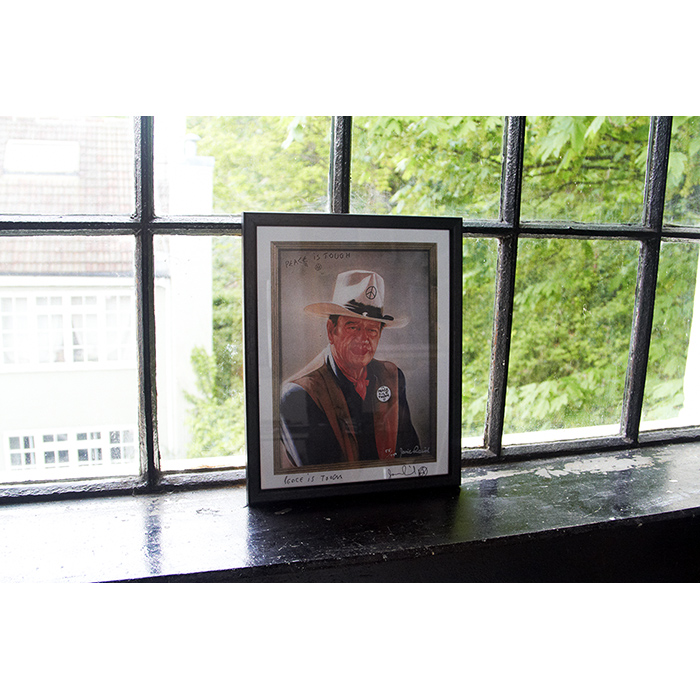

We are in Metway Studios in Brighton; this is a 4 storey low industrial unit. Around 40-50 years ago they used to manufacture electrical products here but in the last 20 years this building was purchased and run by a guy called Mark Chadwick, who is the lead singer/ songwriter for The Levellers. They own this building and the building just to the side.

They’re all workshops and studios for people within the creative industries but there’s also 2 or 3 recording studios here as well, so there’s bands coming through here all the time. There’s lots of young musicians who keep all their equipment here and they tour all the time with The Levellers so they’re constantly in and out with big tour vehicles loading up equipment.

But we’re stuck up in the rafters, if you like, in what is a small space in the back of an open plan loft and I’ve been in this room back here for about 5 or 6 years.

Did you have anyone helping you before Harry joined the studio?

I’ve always had 1 or 2 members of staff, depending on how busy we are at that time with commissions, projects, publishing, gallery projects and that sort of thing. Harry Watts runs the studio; I try not to be here, I’m usually out doing other things like shooting, in meetings, writing, travelling to and from shoots as well as abroad.

There’s another guy called Joe Conway who works here; there’s another half desk in the studio where they do all the scanning and retouching. We have calibrated screens and a calibrated printer to do our test prints.

How would you describe your average daily schedule?

It’s soo different day to day. Tomorrow I’m in meetings and testing equipment. I’ll be on the train to London, I have a meeting at 3pm with an old friend who’s introducing me to a young photographer as I’m writing a small piece about him for Photoworks. I found this guy’s work and I really like it, so I wanted to meet him to have a chat about his practice.

How much of your time is spent writing?

More and more now, because I’ve also started making films, so I have to write treatments. If I’m working on a project like this current one for a drinks brand, they usually also ask me to write a treatment too, to see how I’d approach the project. So we have 2 or 3 briefs on the table at the moment for drinks brands, we’ve got 2 briefs for clothing campaigns, so I have to write on those quite a lot of the time.

Do you enjoy that side of it?

I’m getting to enjoy it; I read a lot. You go to University to learn to write, don’t you. I’m not academic in any way. I’m not that kind of person, but I do enjoy writing. What I’ve started doing is talking with friends and recording the conversation, then listen back on my headphones and writing. I’ve got good mates down here (Brighton) and a couple other friends that moved here from Newcastle upon Tyne…

You also spent some time in London?

I did spend a little bit of time in London, but I’m up in London 2-3 times a week anyway. I do love London and I often think, ‘Oh I could live in London’, but then it’s always nice to get back to Brighton.

Your work centres mostly on youth culture, where did your interest come from?

It’s biographical I think, things I like are usually biographical; films, print, paintings, whatever, and I think that makes the most successful art. For me, my formative years of growing up really helped to define me. I’m still probably a little bit arrested in some ways, in that I still collect soul records, I still have my indie scooters, I still have probably an irrational interest in menswear and clothing.

When I was younger I was very interested in style and music, most people are, I just found success in making pictures around that. What I realised quite quickly, while I was making pictures for Sleazenation and The Face and those kinds of editorials, is that it communicated really well because everyone goes through that period, we’ve all been there, we can all relate to it. There’s a lot of humour in it, there’s sadness, there’s a lot of human moments that are instantly quite gratifying. It always felt like a really great thing to photograph; I feel most alive and most happy when photographing youth culture so I keep doing it.

How did you get involved in the Garage scene?

I got involved in garage because I’ve always been involved in music. I was hugely into soul music and from my early teens I was listening to Motown and all that sort of stuff, via The Who, The Kinks and other 60s mod bands. Then we moved into funk and eventually hip hop, then we started going to the clubs and discos; at that time they were playing a lot of soul and funk but a more 70s-80s version of it.

Then about 86-87 we started getting into house music and a lot of DJs in the north were really pushing house music to the forefront of the club scene. At the time, house music was quite vocal and soulful; I’ve still got a lot of my original house records here from that era when we were growing up.

So then the rave happened down south and spread up north and everyone started dressing in smiley t-shirts with bandanas round their head, with cowboy boots and massive jeans; we didn’t really like that, so my crew splinted a little bit and some went into jazz and real hot jazz dancing, real intense Cuban afro jazz sounds but a majority went into the soul scene, so we went back into 60s-70s northern soul music.

House music started coming into the soul scene and what eventually happened around 1992 was that house music became garage, which then became UK garage. I went away to university and that’s what happened, I was in Brighton and London and that’s what was going on.

In 1997 I was working for Sleazenation and I was asked to go to a UK garage event; we were really into that kind of housey garage sound at the time so I was looking forward to it and it felt just like walking back into the soul scene, so it made total sense. People were making more of an effort in the way they dressed; the scene was very much about black London and that was something that I was missing, really. I enjoyed that when I used to go to soul nights in London, where it was more black orientated, a bit more upfront and also more about dancing and looking good. That’s what it always was for us, about dancing and looking good and having a good time. It’d lost it’s way in dance music in Britain and UK garage clicked with me immediately, I felt like I wanted to be a part of that scene, but not in the same way I had in the past; I wasn’t going out and partying in the same way, I was a photographer, I was making pictures around it for about 3 years and really enjoyed it.

I was wondering what your intention was with the project, because it was shot during that time but you’ve only decided to publish it now.

At the time I was working for publications; The Face might send me to Twice As Nice because they knew I was already going there and I’d say, ‘I’ve already got some pictures’ but they wanted their own pictures. I’d already been shooting for Sleazenation, so I’d been making a lot of pictures there. If I weren’t commissioned to go there, I’d be going there anyway, once or twice a month. They moved to a bigger site in central London, so if I was out with Sleazenation – and I was a lot at that time, out at clubs making pictures of subcultures. I might be taking pictures of some metal kids at The Metro on Oxford Street and round the corner was The End, so I’d pop in on a Sunday night when it was Twice As Nice; I got to know the front of house and they’d let me in.

I remember Arena mag sent me out to Ayia Napa and I was out there for a week and made tons of pictures; that was at the absolute height of the garage mayhem in Ayia Napa.

So anything that wasn’t published in the magazines, you’d keep for your own projects?

Well nothing from that trip was published in the end, but as a working photographer trying to make a living, you wanted to work for good publications. You used to be able to make a living working editorially, to an extent; it was your bread and butter. So if they didn’t run the pictures I’d almost give myself a little high five as I didn’t have to share it.

But if you were working with art directors like at The Face and Sleazenation, they would work with you quite carefully to make sure you got the right pictures in their magazine. In the end they would only run about 5 images, whereas I would’ve shot around 500, so there’s always a plethora of unseen work and therefore you can make a book. I’m realising more and more, you can make a book 10 years later, so I keep photographing scenes.

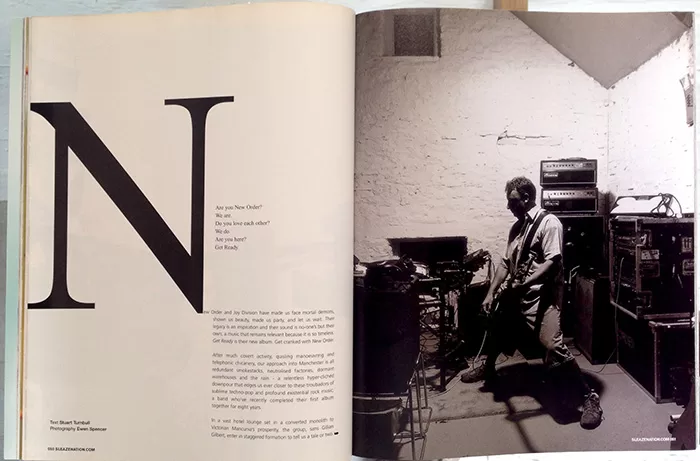

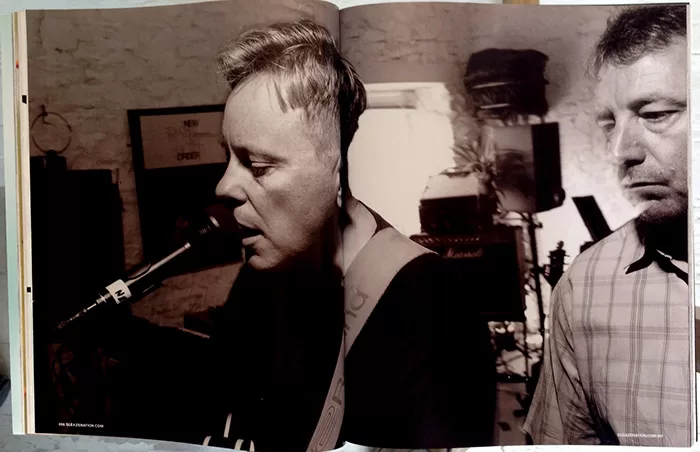

Spreads from July 2001 issue of Sleazenation, New Order shot by Ewen Spencer

Following on from garage, you started getting involved with the grime scene. I read an interview with you from last year in Vice and you stated you weren’t really into the music, but the energy and attitude of the scene. How was your experience compared to the garage scene?

I was interested initially because it’s not about the clubs; what I was doing was going into people’s lives, I was going into youth centres and peoples homes and the events they were having. The scene is much younger and they weren’t going out to clubs so they were a little more hesitant to let you into their lives.

Especially for me, a 30-something, white, male, who probably looks pretty middle class to them, to them being young, predominately black males from East London who were full of energy and excitement, so I tried to capture that. It was a longer process and really enjoyable because it was much more about being British and being young than about the dance floor, than about the club scene. Although the pictures from the garage scene still speak about that, the pictures from Open Mic were capturing what was happening up and down the country at that time. It was capturing that energy of young people being creative, when there’s not at lot really in front of them; there’s not a lot of opportunity. You’re talking about kids that were growing up on the streets of London where Stephen Lawrence had just been stabbed to death, black on black violence was getting out of hand and they were trying to rein it in all the time, so you had that lingering around as well.

So what you had were people discussing that; that’s what they were talking about, these kids. They were mainly working class kids; I was out in places like Romford and Leytonstone and Limehouse; it felt like a great time. If I think about it now, as we sit here, it fills me with joy; there is something about the energy of youth.

Was the project self initiated?

Yeah, they all are. I always try and make pictures of youth and I was making these very generic images that were very successful and were shown at The Barbican and nominated for an award at Arles; I was selling prints and it was very exciting, but the pictures felt generic to me and I was looking for something more specific like garage, and grime was there. I found out about it quite early on because I was working with Mike Skinner from The Streets, making the artwork for his album covers and he introduced me to some of these young MCs he was working with, so that’s how it came about.

I can imagine it would’ve been quite difficult getting involved without having connections to the scene already…

I had 1 or 2 connections in there to initiate it, then it became a real labour of love and it was hard work; I had to pester people, I had to door step people and continually do so. Mobile phones were becoming more accessible so most people would have a little Nokia and I was just calling people; endlessly calling people. I would get my equipment ready in the morning and get on the train from Brighton up to London. I’d go to Leytonstone where I knew a few of the people would be. Jammer was there; there were 2 guys called Ratty and Capo, who were not too far from there, who were making these DVDs called Lord of the Mics, which were very, very popular on that scene; this is before YouTube and Facebook, you have to put your head back in that time. They were distributing these DVDs and selling thousands of them, up and down the country.

They used to occasionally come and pick us up from Leytonstone station; I think they felt sorry for us, but they’d be on there way to make a little film about themselves, about 2 kids that are having an MC clash and I’d go along with them. I started showing them the pictures and eventually the kids there that I was photographing. At first they were very reluctant, but I’d start going along to these events with Ratty and Capo and I’d take my photos with me; they’d see the prints and they’d love it. So it definitely helped the project along.

What do you think of the current garage music revival?

I don’t listen to it; I mean I listen to garage but probably on a night out, really. I listen to soul more than anything but I do listen to a lot of different music as well. I’ve recently been listening to Suicide, Brian Jonestown Massacre, The Lars. I listen to underground house music on the radio occasionally and if a new garage tune came on I might think about it but I wouldn’t really be that bothered about it.

I love the fact that the DJs and the scene from then are getting love now. A lot of them are also into a myriad of music; they’re not just stuck in one place. But going back to your question, I’m not that into the new garage revival, I mean it served me quite well, we had no idea that the garage revival was happening, and then guys like Disclosure came on the scene.

A lot of the garage guys we were working with when making Brandy & Coke, they’re busier now than they ever were back in the day; they’ve got a younger fan base now and a lot more people are taking interest. When it first started to become popular, garage was an older scene. These films that I’ve made, have really helped these guys as well. It’s put them back in the spotlight, as it were, which is great; it wasn’t my intention to do so but I’m glad it’s happened for them, I just wanted to make a film about something I was interested in visually.

Was it your first time directing a film?

I’ve made a couple of little films; one was for Massive Attack about 4 years ago. They were commissioning around 8-10 artists to make a film for a track from their latest album, Heligoland. They liked the stills work from Open Mic and asked if I could make something like that, something quite real and about young people; Massive Attack are like the arch collaborators, aren’t they, so it was really nice to work with them and make this little film, with direct input from them. So I’d send them rushers and they’d respond directly; it was an amazing creative project and I was very fortunate to start making films in that way. To the frustration of some people, I didn’t rush into filming, I just waited and that was the right project for me; it made sense. It eventually became a pop video and it received a lot of attention at the time.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’ve just come back from Miami where I’ve been making pictures on spring break, so now we’re processing and art working these pictures and have given them to the art directors in Berlin to produce a zine, which will be a little bigger than the last one because there’s soo much material. I was out there for around 9 days, shooting everyday; you become quite disciplined. I’m writing for another short documentary film and working on some ideas for a possible longer film as well. Besides that, we have around 4 or 5 treatments for advertising campaigns.

Also, we have a special limited edition gold version of UKG, which comes with a print and we’re also selling a limited edition run of 20×24 prints from the project as well.

Ewen has kindly put together his studio top 5 soul tracks for June from his own collection, click the records below to listen to his selection!

(Photographs courtesy of Ewen Spencer)

Artist: Sheryl Swope

Track: Can’t Get Him Out Of Mind

Label: Duo Records

Mike Terry arrangement means it’s likely to be a good tune. Sure enough this is a wonderful gospel influenced dancer that is in poor knick but much cherished.

Artist: Diane Cunningham

Title: Certain Kind of Lover

Label: Fontana

Laconic, Eugene record penned, mid paced tune from the mid 60s. There’s a fragility to her voice that sounds so sad. The brass arrangement and basement bounced rhythm section make this a winner.

Artist: Jeany Reynolds

Title: Please Don’t Set Me Free

Label: Mainstream Records

I picked this up around 10 years ago from a dealer in Yorkshire. I’ve never seen or heard of a copy since, totally overlooked piece of real soul.

Artist: Leroy Taylor

Title: Oh Linda

Label: Brunswick

Pure joy from the 80s Stafford era. Possibly a Guy Hennigan spin? No matter, it’s got a great bassline.

Artist: Larry Atkins

Title: Lighten Up

Label: Highland Records

Such a beautiful song, brought to life in this slightly more easy to own 1960s issue on Highland. I played this at a friends party once and Ady Croasdale got up to dance. Fact.