Alec Soth – Songbook

All spreads © Alec Soth 2015 courtesy MACK

Songbook by Alec Soth, (MACK, 2015, 1st edition, 2nd printing), BUY

The seismic changes that have reshaped the landscape of contemporary life in recent years are largely the product of forces that seem almost too abstract to grasp in their totality. Their effects were – and are – real enough, however, as the final erosion of those certainties that post-war generations were able to take for granted. It was precisely the globalised nature of our economic structures that meant the sorcerer’s apprentices who had conjured up these vast, transnational entities could no longer restrain their creation. Corporate interests have had an undeniably destructive influence on fiscal policy, especially in the removal of prospective safeguards against the accelerated cycles of boom and bust that have increasingly rocked the world. After the most recent crash, this proved to be true of those who advocate the oxymoronic free market as well as the prophets of centralised administration, given that the response of both ultimately seemed to converge on the single panacea of “austerity” as a cure for all economic ills.

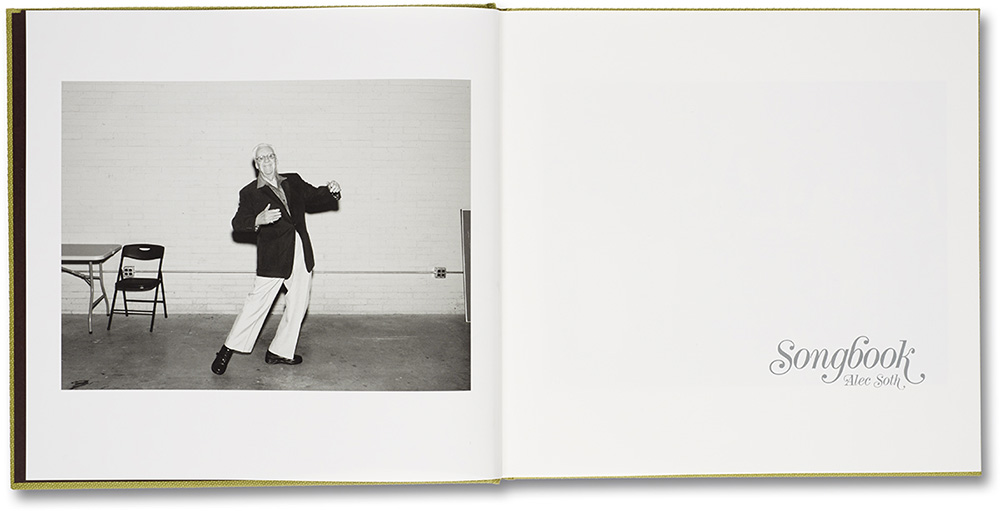

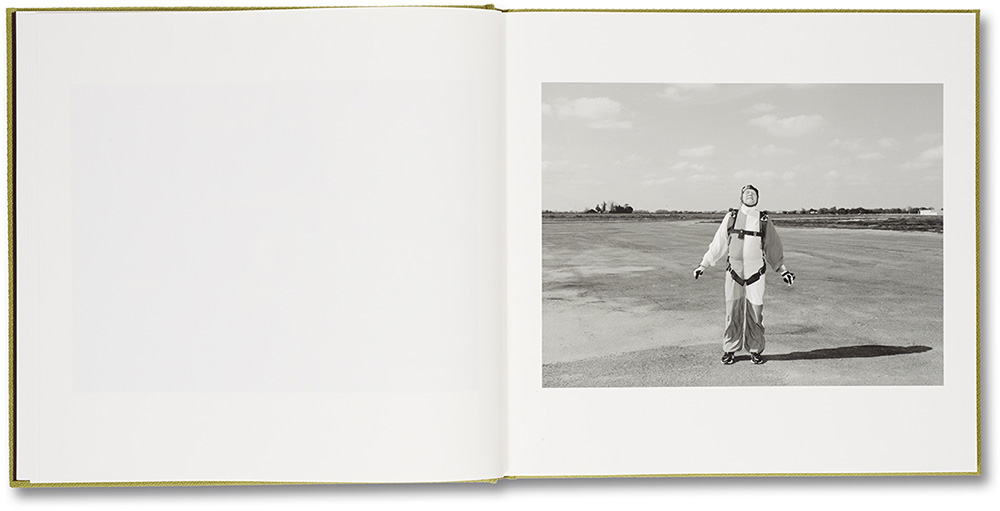

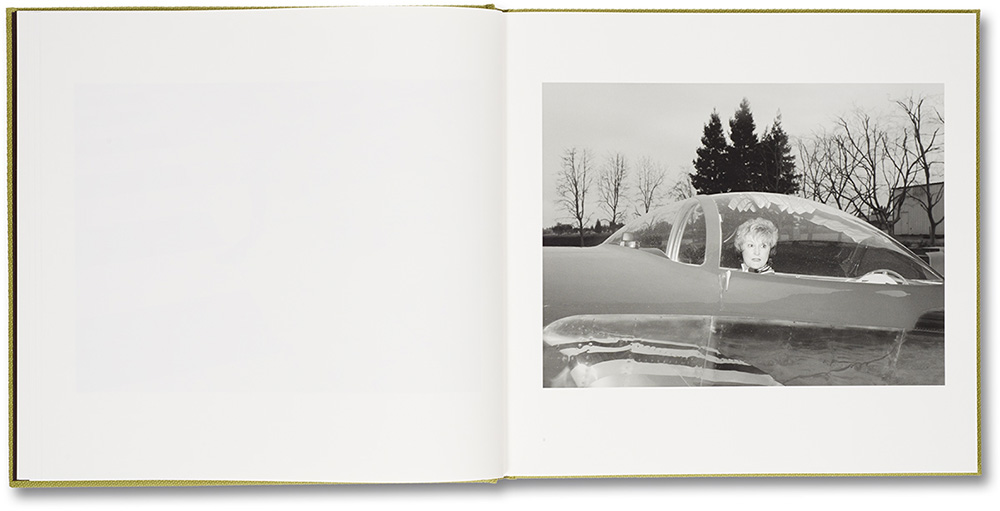

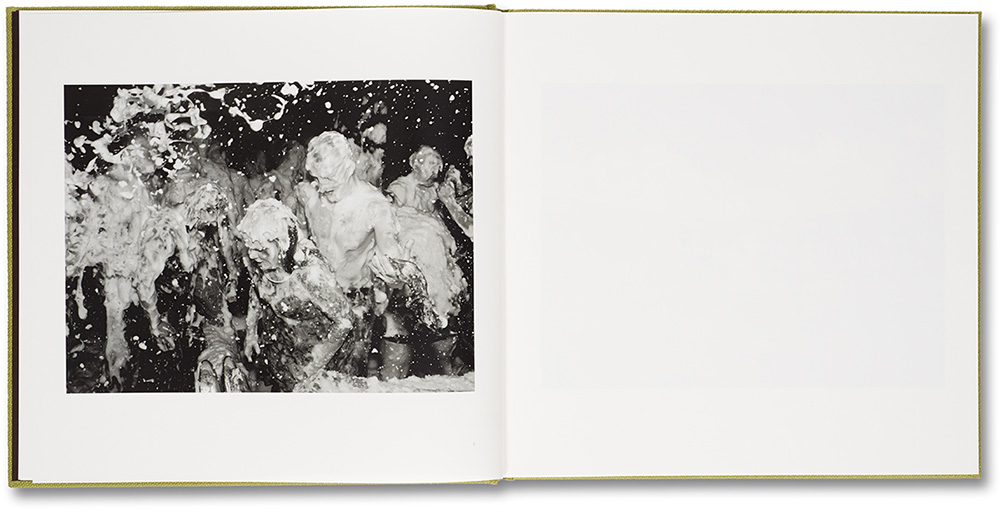

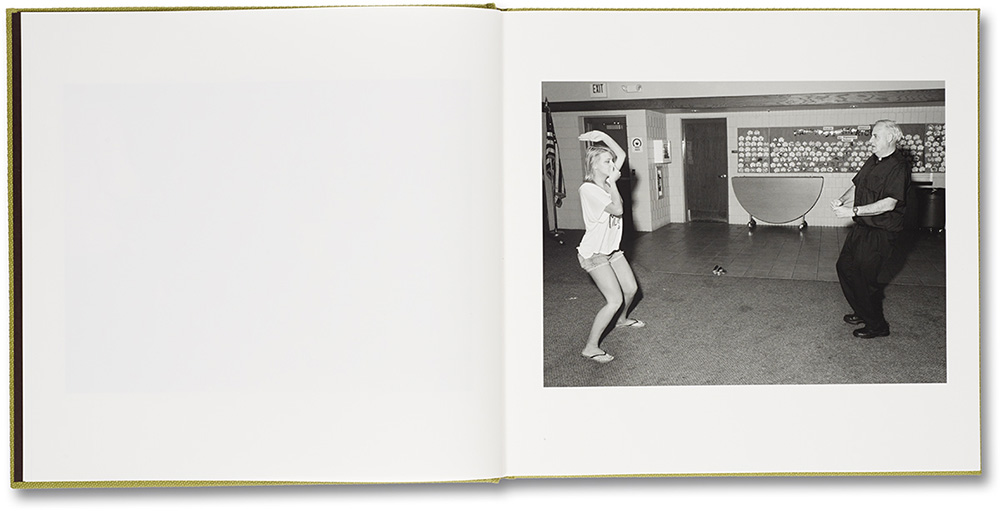

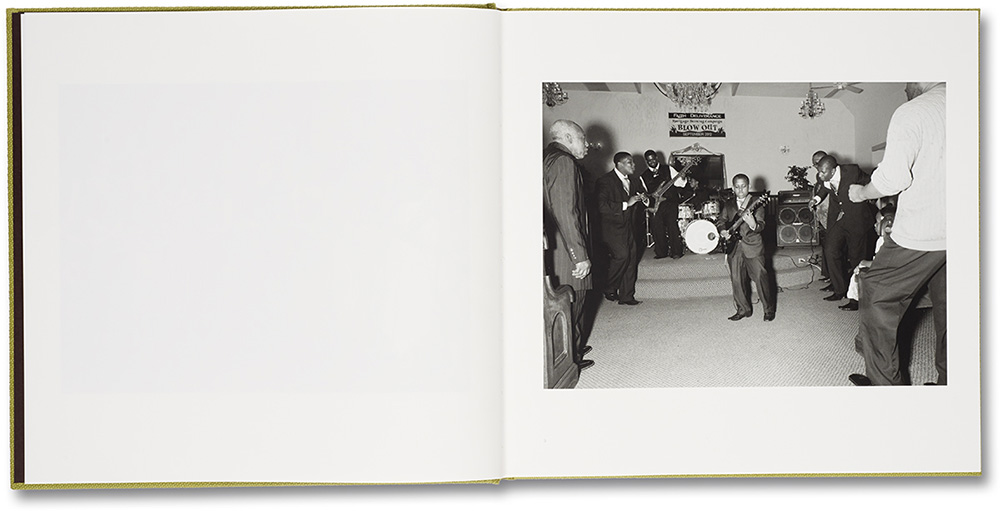

These changes are exemplified by an alarming wealth disparity and its attendant sense of social disconnection. It is exactly these that Alec Soth addresses in his latest publication, Songbook, which also marks something of a stylistic departure for Soth, even though his fond attention to the folksy peculiarities of American life remains very much intact. This is a world rendered in stark monochrome, often flash-lit and the tone is decidedly cold, if not necessarily in terms of how Soth appraises what he is seeing; rather the coldness is there waiting to be discovered. The static framing of his earlier work has also been supplemented with seemingly more casual encounters and scenes of arrested movement. This book collects work made while travelling with writer Brad Zellar for their self-published newspaper project (The LBM Dispatch) and also on assignment. Admittedly mixed in subject and even in approach, the book never lapses into the sort of disjointedness that this “anthology” format might suggest, but neither can it entirely rise above these origins.

To the extent that it does succeed, however, Soth has fashioned a vivid, often haunting portrait of a society struggling under the weight of its own contradictions, chasing the same hollowed out dream of shared prosperity in an age that has made it simply impossible to achieve. This sense of failure is etched on the face of the woman reduced to collecting cans, but equally, and somewhat paradoxically, the same exhaustion can be seen in the slumped posture of the grimy oil-boom worker, given that they are both the product of a fundamentally unstable economy that profits only its shady manipulators while everyone else merely struggles to stay afloat. In the manic cycles of contemporary capitalism, the former distinction between good and bad times has now become largely arbitrary, not least because the community integration that might once have shielded vulnerable individuals against the worst ravages of this volatility is now little more than a nostalgic remnant. The longing for – and the destruction of – this notional community emerges as Soth’s essential theme here.

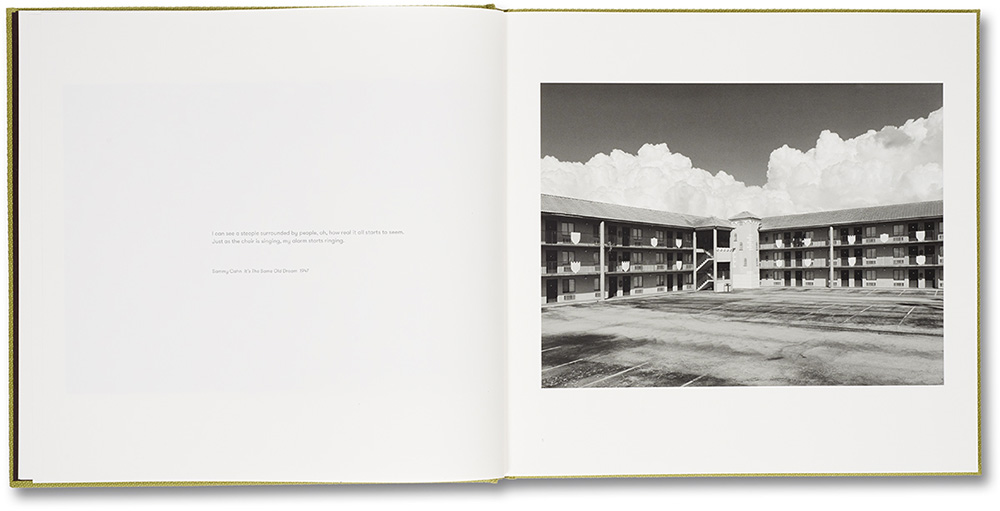

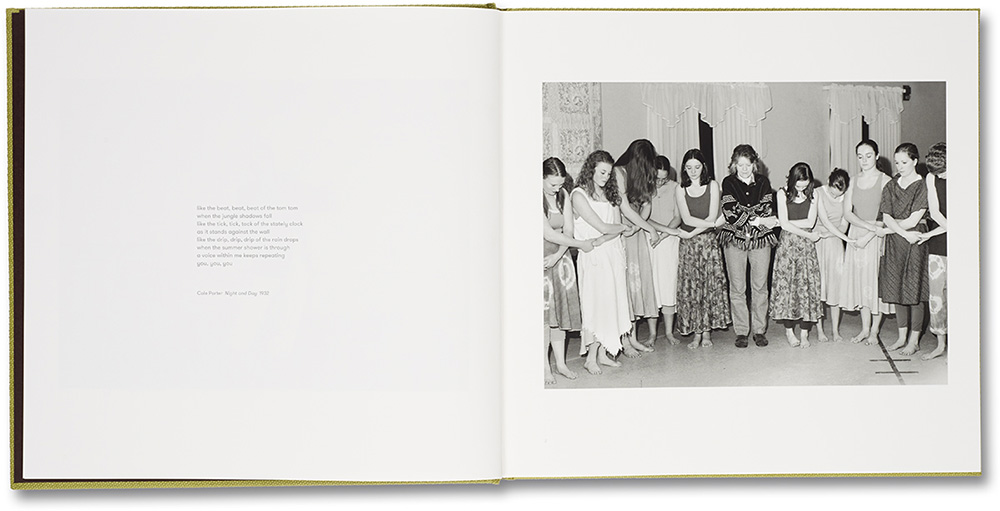

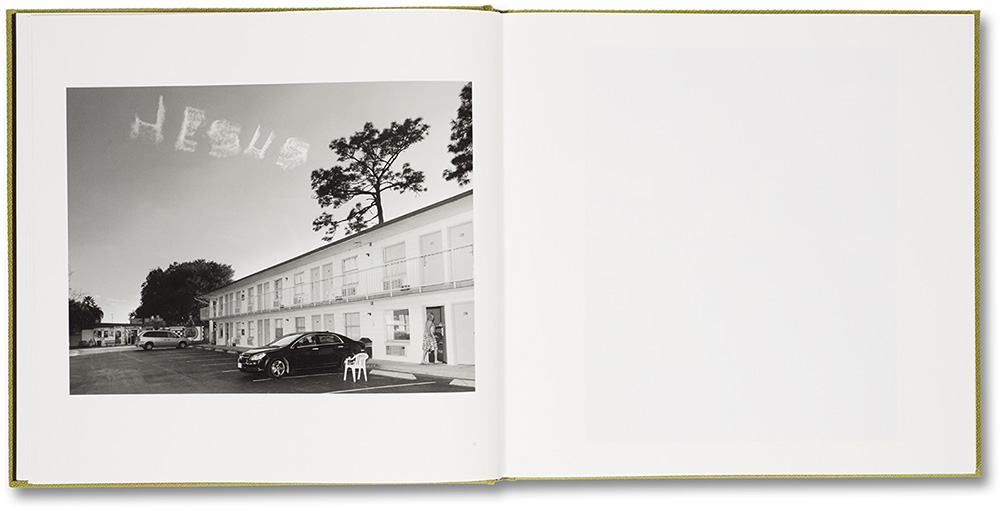

What structures the work (and supplies its title) is the selection of quotations from popular songs that Soth has interspersed between the images. Even the very idea of “popular song” conjures up the sense of a shared or collective experience of culture, a common set of reference points that seems increasingly distant in our present media landscape, which is defined by nothing so much as its fundamental atomisation. The inclusion of this material, then, can only be intended to suggest that we are not longer singing from the same (proverbial) hymn-sheet. Unfortunately, it also reveals a certain degree of rhetorical clumsiness that is at odds with the kind of sensitivity he otherwise demonstrates. This extends to the pictures as well, a number of which seem to be animated by a rather unwelcome didactic urge. In these instances Soth goes against his best instincts as a photographer and the occasionally hectoring tone betrays the origin of his material as largely having been made for illustrative purposes.

That being said, Songbook remains a complex achievement, one that still manages to describe the intersection of personal and emotional landscapes with the economic, historical one. What’s striking of course is the relative – and the visual – darkness of Soth’s portrayal. He is hardly the first to point out the paradoxical fact that in an age with an abundance, even an excess of technology for communication we seem to be more disconnected than at any other time in history. No doubt this is because the social changes fuelled by the technological boom have sundered traditional community relations. Many of Soth’s pictures here look at the ways in which Americans have retreated to idealised versions of their shared past in order to remedy this sense of disconnection. But the tragic irony of such “traditional values” also being espoused by the very politicians whose economic manoeuvres have made their return all but impossible will not be lost on anyone, as it certainly doesn’t seem to have been lost on Soth.

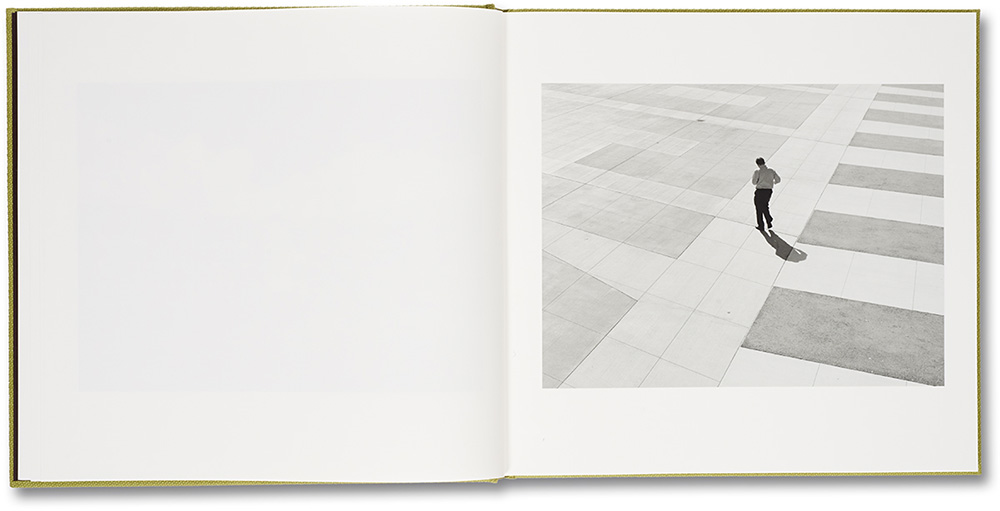

Where this is most insistently dramatised is in the repeated depictions of isolation, whether it is of people or of buildings, which are seen as both metaphorical stand-ins for the state of human society, often shown surrounded by a hostile, nearly alien nature and as a measure of infrastructural change, pitting the hand-made and the domestic against the bland facades of corporate monoliths, such as the one pointedly shown in the closing sequence of the book, the uncertain shape of things to come. Songbook also appears to be a transitional moment in Soth’s practice as a photographer. This change is not just the obvious stylistic one and neither can it be seen as the loss of his empathetic attention to the everyday. Given how it originated, it is no surprise that the impulse behind the work now seems more open-ended, but its real importance is precisely in his willingness to engage with the broad scope of American life, even if the result is not the definitive statement it might well have been.