Arturo Soto: Vanishing Point

from the series When The Time Comes

The notion of place is one that can appear deceptively straightforward, as nothing more than a series of spatial and geographic contingencies defined by whatever happens to be there at a particular moment. This is often a considerably striking issue in photography, where the medium not only facilitates superficial readings, but actually affirms the immediacy of such an impression; everything is seemingly left to chance, with no deeper structure at work. The ease with which photography generates surface judgements also encourages the absence of ideological questions in considering the arrangement of our built environments. But the experience of place as such is fundamentally related to (and indeed, actively shaped by) forms of social organisation, both in terms of how its contours are drawn and how the very idea of place, of belonging, determines our identifications.

Perversely though, much of Arturo Soto’s work seems to be about those aspects of a given place that we are not liable to see at all. Our understanding of the landscapes that surround us tends to be more driven by familiarity and by expectation than by the sort of acute enquiry that Soto brings to bear. If the camera can easily gloss over the political and historical dimensions of a place, it can also – and with equal intensity – be used to reverse some of this complacency, to look again at the accumulation of details and relationships that make up where we live. Soto’s Blind Views is an examination of the landscapes we might otherwise be oblivious to – including the sort of architecture that barely rises above the functional and those long stretches of nowhere in particular that now punctuate our lives. In many ways, Soto’s subject is the space that exists on the edge of the officially sanctioned view. It opposes the predetermined understanding that, in effect, teaches how to see a place in accordance with established forms of social and economic power.

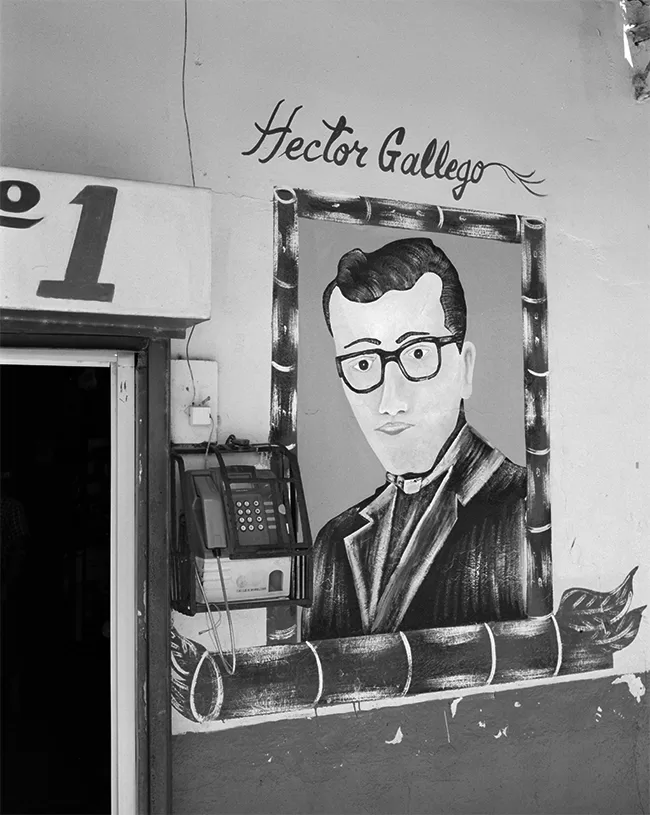

By contrast, Blind Views is a recognition of how seamlessly integrated those forms of power are into virtually every aspect of the social landscape. Our reluctance to see this continuity is, in itself, a condition of how those relations are perpetuated. These power relations are manifested in the spatial and structural experience of the social landscape, as well as, of course, the way in which it is represented. Similar questions are raised by Soto’s series In the Heat, where shifting perceptions of a place or a landscape are established in equal measure by subjective experience and ideological pressures, especially pertinent in the case of Panama, which Soto takes as his subject here. Of course, the canal dominates most of our thinking about the country, both in the popular imagination and in politics, but it is hardly glimpsed in Soto’s pictures at all. The contested history of international interest and intervention in Panama remains a key point here though, suggested by the way Soto frames each particular view, often as the sum of its own unresolved discontinuities.

What is stressed in both cases is the essential reciprocity between a lived, dynamic encounter with a place and the social or historical forces that have shaped it. Soto’s pictures also mark, however, the blind-spots that might otherwise obscure the fundamental nature of this relationship – those aspects of a place we can’t or don’t want to see. Perhaps surprisingly, then, for pictures that appear on the surface to be concerned with the minutiae of decidedly unremarkable places, their critical edge is directed at the ideological underpinning of the social landscape as a whole. When considering a particular view it is necessary to understand how much the static frame of our gaze cannot accommodate; Soto’s notion of place is broad enough to acknowledge the extent to which physical contingencies and social organisation are inextricable.

Our reading of that view within and through the picture is the product of conventional assumptions about how space as such can be seen and understood. Soto does not treat the structure of his pictures aggressively; they are for the most part relatively stable depictions of real places. But, at the same time, they acknowledge how any view (that is, any pictorial space) is the result of an ideological dialogue, even before it is seen at all. The notion a ‘view’ implies that the spectator is positioned in a specific way, resulting from a set of decisions about what to show and how it might be seen. This is necessarily tied to existing social and economic structures, just as, for example, the ordered spaces of classical perspective speak to at least the aspiration of a correspondingly mechanistic social order. But the picture can also be used against our assumptions, and this is true of Soto’s work, which consistently emphasises those aspects of a landscape we inhabit but don’t really see.

from the series When The Time Comes

from the series In The Heat

from the series In The Heat

from the series Blind Views

from the series In The Heat

from the series When The Time Comes

from the series When The Time Comes

from the series When The Time Comes

from the series Blind Views

from the series In The Heat

from the series Blind Views

from the series In The Heat

from the series Blind Views

from the series Blind Views