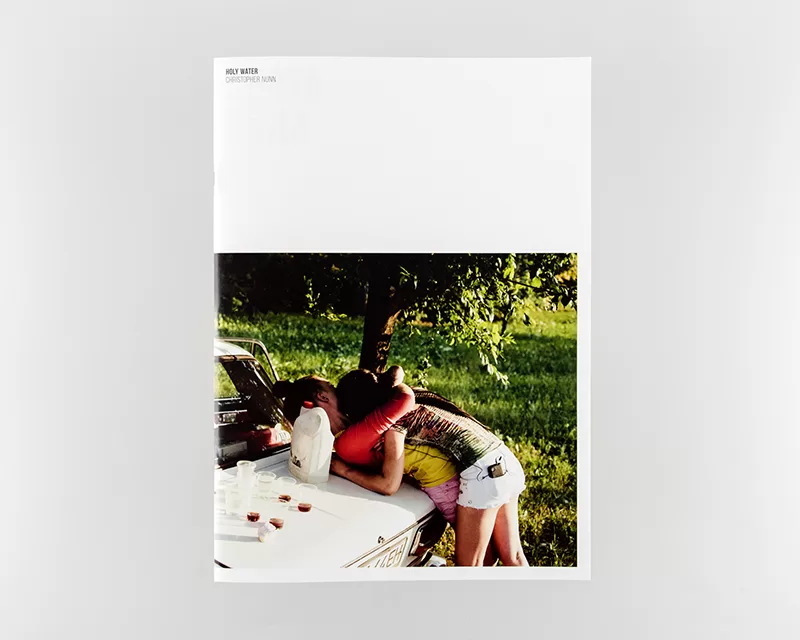

Christopher Nunn – Holy Water

The reasons why a particular place or region captures the attentions (and imaginations) of photographers are often obscure; perhaps it might speak to some assumption about the times or merely offers the kind of ‘picturesque’ subject that has always unfortunately dogged the medium. In many ways, the fate of the post-Soviet countries can fit both of these categories, which isn’t to say that they haven’t also attracted any number of capable photographers making serious work, but rather that in this context it is increasingly difficult to tell real stories that stand apart from the treatment of issues that are now too familiar to be meaningful. However, Christopher Nunn’s work in Ukraine is a good example of a photographer finding their own voice, even when dealing with what otherwise might be seen as well-trodden ground.

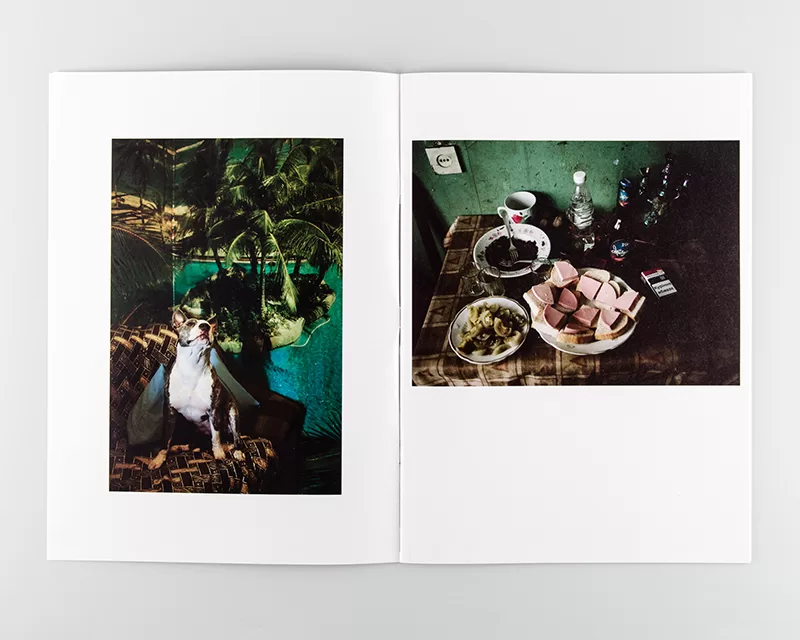

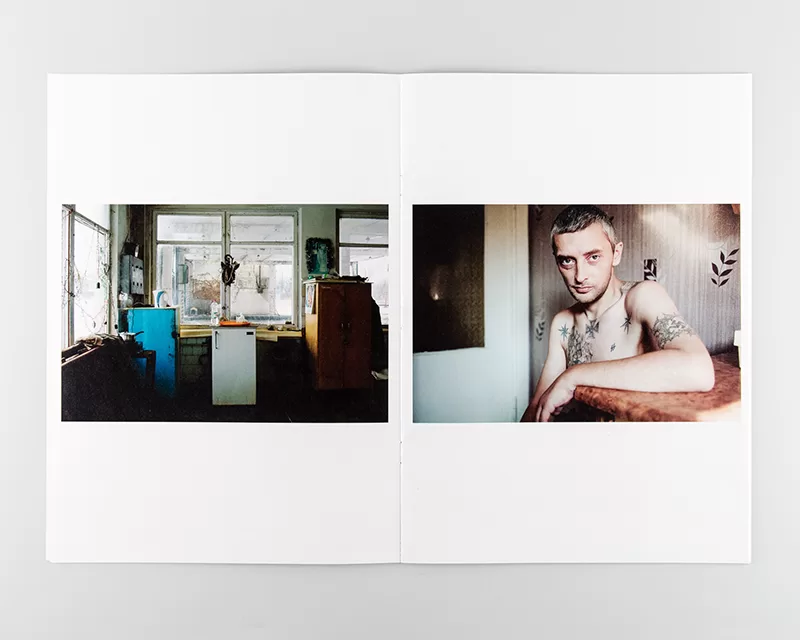

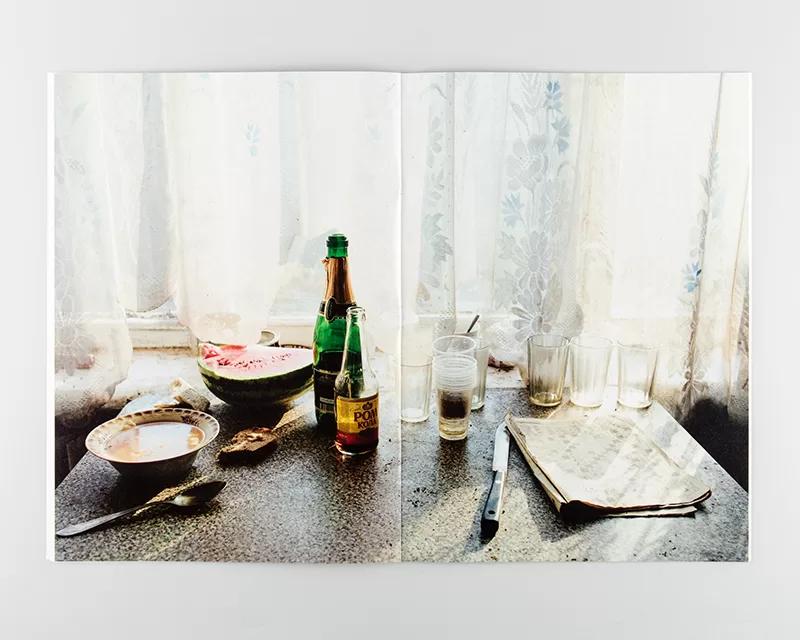

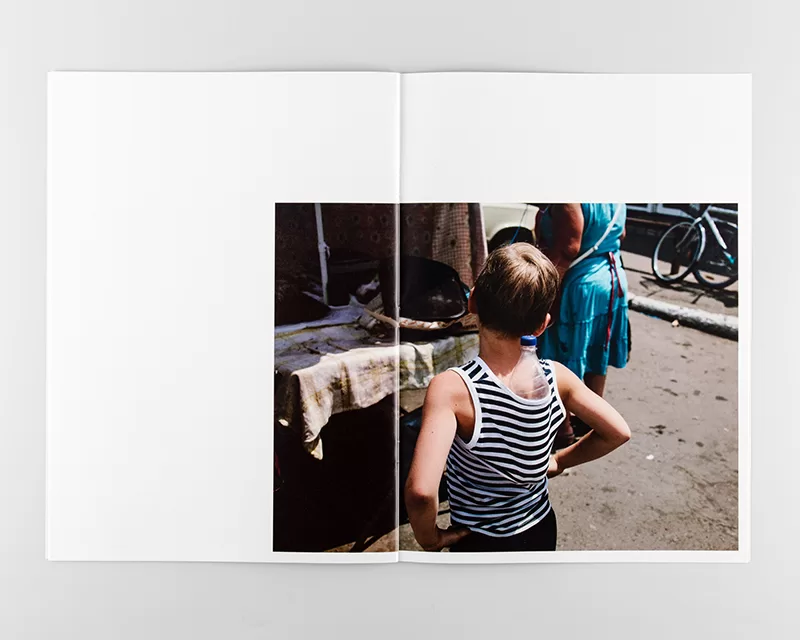

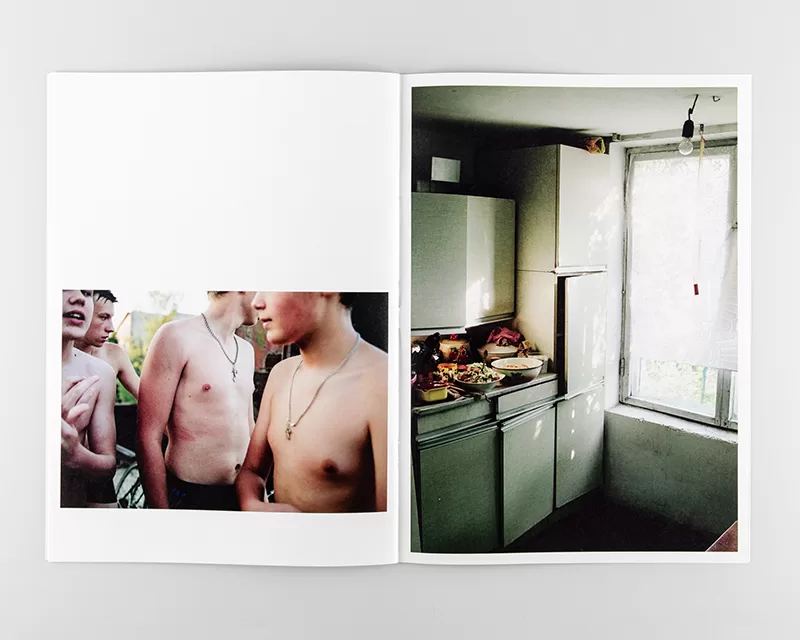

His book Holy Water (Village, 2015) is an excerpt from a larger on-going project made in the region, which has never been far from the headlines in recent years. Nunn chooses not to concentrate on the more spectacular aspects of conflict or civil unrest, but, with this portion of the project at least, gravitates towards scenes of domestic life and to the marginal areas away from the cities, where some continuity with the past can still be discerned. As a result, these are intimate pictures, studies in the character of a place, its local mood, rather than claiming any definitive insight into the larger geopolitical issues that might be at stake. So instead of attempting to impose any kind of photo-journalistic objectivity, Nunn presents us with a series of encounters that trace out his experience of a place and its people in a diaristic fashion. At the same time though, we must recognise the extent to which the textures of ‘the local’ are still implicated in larger narratives and perhaps, today, there is no better means of approaching those themes, except from underneath.

The continuity that is implicit in these scenes is with a pre-Soviet notion of community that had perhaps more tenaciously embedded itself in such rural areas, but that now strangely co-exists with the usual effects of the Soviet collapse, lingering still. It’s subtle, but Nunn does appear to be hinting at how this notion of community is being undermined by the legacy of the collapse maybe even more so than it was by the Union itself, a fear given credence by the looming threat of Russia’s present territorial claims in the region, claims backed by that country’s increasingly dictatorial governing elite. So in this sense, conflict is still at least a subject of these pictures, if by no means the only one, and Nunn has found a gratifyingly elusive way of signalling it.

The people he has photographed are simply living their lives and Nunn certainly does show that, but they (and he as well) must know that those lives are also the product of a history that is unfolding all around them and that the world they inhabit has equally been shaped by it, so that the choices available to them are, in a way, already made. By placing our sense of that history in a living context, showing the places and people that it affects, Nunn is suggesting the extent to which historical forces necessarily play out in the domain of individual lives, even if, as in most cases, those forces seem to have a decidedly impersonal scale. Though made by a relative outsider, his intimate pictures direct our understanding of those forces away from the headlines and the realm of political spectacle; what remains are the people who must live with history, rather than those who make it.